Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Yoshio Akioka

Industrial designer, lifestyle designer

Date: 27 July 2018, 10:30 - 12:00

Location: Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo

Interviewees: Chikako Furihata (Curator, Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo) *She is now a curator of &4 + do.

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro and Aia Urakawa

Author: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Yoshio Akioka

Industrial designer, lifestyle designer

1920 Born in Kumamoto Prefecture.

1953 Founded the design office KAK with Junnosuke Kawa and Itaru Kaneko

1969 Left KAK to set up his own private office "104 Meeting Room"

1970 "monomono" was founded in Nakano, Tokyo as a base for the craft design movement.

1981 Establishment of DOMA Studio in his house.

1997 He passed away.

Description

Description

Yoshio Akioka was not only an industrial designer and lifestyle designer, but also a painter for children, a woodworker, a writer, an educator, a producer and a collector of tools. In the early days of post-war design, he was active in a variety of fields. He challenged society to stop being a consumer and start being a user, and in order to restore the original relationship between the maker and the user, he pursued the creation of products that could be used for a long time and enrich people's lives. Although Akioka's stance and ideas have many followers, his name is not well known in the design world or in the general public. Perhaps this is due to the fact that Akioka's work was mainly industrial design for manufacturers in the 50s and 60s, and from the 70s onwards he worked with local industries and on local activities, always keeping his name anonymous.

Until then, no one had done any research into the archives of Akioka and KAK, who left a significant mark on post-war design. In the 2000s, the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo was the first to start researching the archives of Akioka and KAK, and in 2009, with the help of his family, began to sort through the vast amount of material that remained in his home. The exhibition "DOMA Yoshio Akioka Exhibition: Design of Thoughts and Relationships to Things", which was held at the museum in 2011, revealed the full picture of Akioka's wide-ranging activities and his advocacy of the ideal relationship between design and daily life.

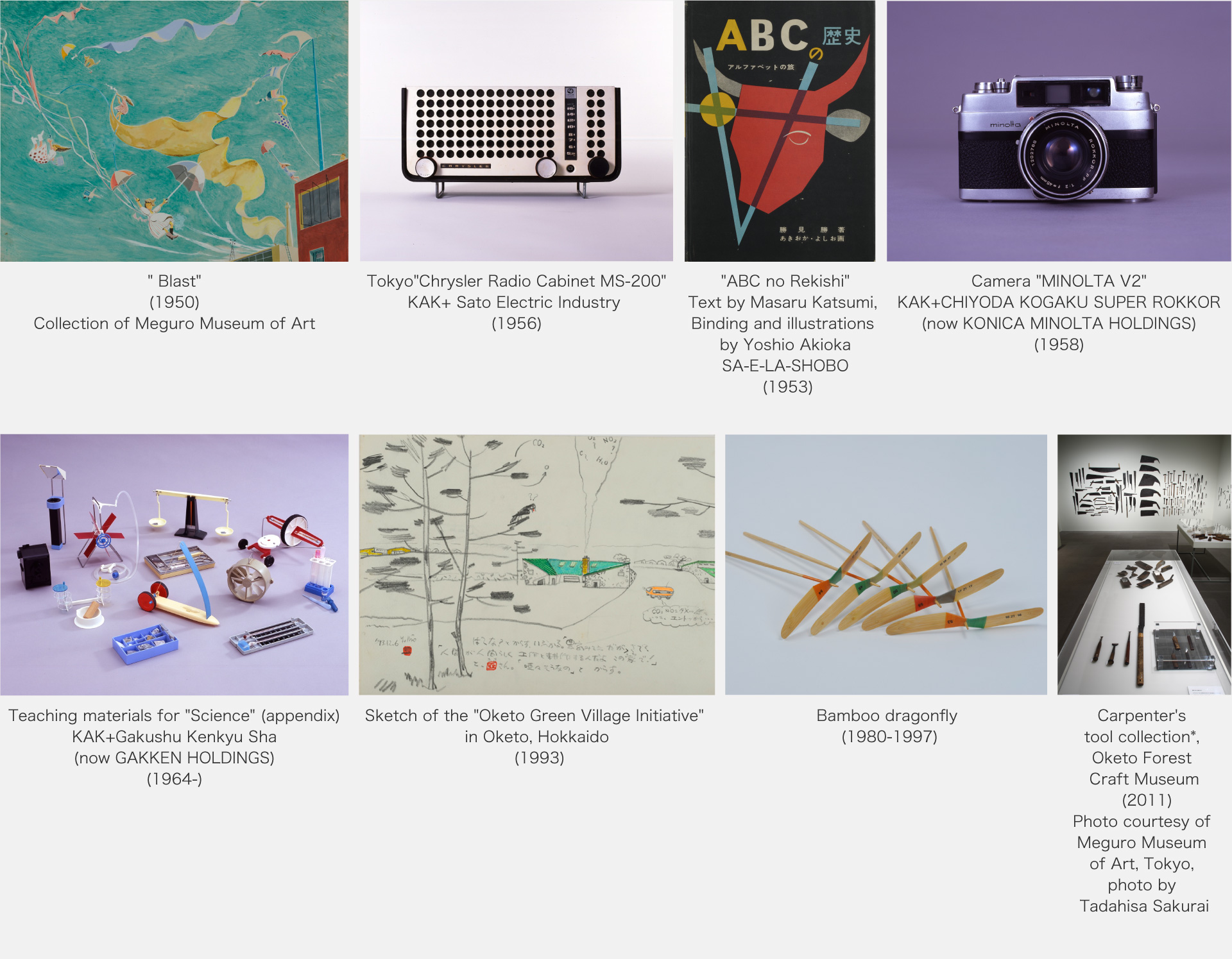

The research was also wide-ranging, as Akioka's post-war work on furniture for the Occupation forces, his children's drawings, toys and prints, and many other unknown works that he did before or at the same time as his industrial design work remain. His work includes children's drawings, industrial design, furniture design, woodwork, his collection of carpentry and household tools, magazine supplements, and his life's work of 3,000 to 5,000 bamboo dragonflies. He is also the author of many books on his own ideas about making things. The Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo is planning to continue its research, as there are still some materials to be started. We spoke to Chikako Furihata, a curator(retirement in 2019) at the museum who was involved in organising Akioka's archive and a key figure in the research.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Products

"Chrysler Radio Cabinet" KAK+ Sato Electric Industry (1950-1960), "LILAC" KAK+Marusho Motor (1950), "MINOLTA" KAK+ CHIYODA KOGAKU SUPER ROKKOR (now KONICA MINOLTA HOLDINGS) (From about 1958), Exposure meter KAK+SEIKO ELECTRIC INSTRUMENT INDUSTRY (now SEKONIC HOLDINGS) (From about 1955), Teaching materials for "Science" (appendix) KAK+Gakushu Kenkyu Sha (now GAKKEN HOLDINGS) (1964-)

Furniture

"Man's chair for sitting on" (1980), " Parent and child chairs that can be combined" (1981)

Books

"ABC no Rekishi" Text by Masaru Katsumi, Binding and illustrations by Yoshio Akioka SA-E-LA-SHOBO (1953); "Waribashi kara Ka made Shohisha o yamete Aiyousha ni narou! " Hakuju-sha (1971), fukkan.com (2011); "Kurashi no ri dezain Seikatsu de hakarinaosu" Tamagawa University Press (1980); "Taketonbo karano Hassou – Te ga kangaete tsukuru" bluebacks.kodansha (1986), fukkan.com (2011); "Mokko – Sashimono gihou – Mokko no omosirosa o sirutameno Koukyu gihou nyumon" BIJUTSU SHUPPAN-SHA (1993); and many more

Related books

"DOMA Yoshio Akioka Exhibition: Design of Thoughts and Relationships to Things" Edited by Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo, Published by BIJUTSU SHUPPAN-SHA (2012)

Interview

Interview

It's important to take the time to organise it patiently and steadily.

I interviewed everyone involved anyway.

Furihata Recently, I have been hearing about archive activities here and there, and it seems to be increasing. Ms. Yoshiko Sawa, a professor at Tokyo Zokei University researched the materials of Ms. Yoko Kuwasawa (a clothing designer and founder of Tokyo Zokei University and Kuwasawa Design School) and published a book ("Futsu wo Tsukuru: Kurashi no Dezaina: Kuwasawa Yoko no Monogatari" Bijutsu Shuppan-Sha, 2018) at the beginning of this year. The Keio University Art Center has a collection of materials by Tatsumi Hijikata and Shuzo Takiguchi, and they are now being organized in earnest. Is it time for everyone to think about archiving? Do you have a guideline for the way of thinking about archives in this NPO PLAT?

― The idea behind this project was to hear the stories of the designers while they were still alive. We ask them what materials they have, how they store them, where they keep them, and what they think about the lack of a design museum in Japan. We are hoping that once we have gathered a certain amount of feedback, we will be able to do something with it.

Furihata That would be wonderful. I also thought it was important to have interviews when researching Mr. Yoshio Akioka, so I went through various channels to meet the people involved and interviewed them anyway.

― I think the interviews are a valuable part of the archive. You've been researching Mr. Akioka's work for quite some time. What was the impetus for this?

Furihata Mr. Akioka was an industrial designer with a strong connection to Meguro Ward and the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo. The Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo was opened in 1987. When we decided to run the museum as a foundation, we asked Mr. Akioka to be a member of the board of trustees, and he also helped us to create a collection of teaching materials, "Drawers: The Museum inside - Wood", which we had planned to use for educational activities before the museum opened.

The Drawer Museum is a system of drawers, in which the four categories of art materials, metal, paper and wood are presented. In the course of having experts supervise the different materials, Mr. Akioka gave us advice on the composition of the wooden drawers. In the 80s, Mr. Akioka was particularly known for his work with wood, and it was around this time that he began to introduce wooden household utensils made by local craftsmen and to produce bamboo dragonflies.

― After that, why did you decide to organize his archive?

Furihata During the preparation of the exhibition " Drawers: The Museum inside - Wood", I visited Mr. Akioka many times at his DOMA in his house to talk to him about wooden materials, and I saw a beautifully coloured children's painting in his room. Someone told me that Mr. Akioka used to paint children's pictures, that he designed furniture for the Occupation forces after the war, and that he worked for a design group called KAK, which was involved in the design of MINOLTA cameras and MITSUBISHI PENCIL's "uni". He was a man who didn't talk much about his past, so I was very interested in the connections between the past and the present, and what had happened in between. In a way, it's like a curator's intuition. In the 1990s, there were exhibitions of Mr. Sori Yanagi and Mr. Isamu Kenmochi, and there was research going on, but no one had done any serious research on Mr. Akioka. At first I was at a loss as to who to ask, but it was a great privilege for the curator to be able to conduct research from the very beginning, which is not often the case.

The more I looked into it, the more I understood.

― When did you start researching Mr. Akioka's archive?

Furihata After Mr. Akioka passed away in 1997, some people thought it was too early to start researching the archive, so I didn't start immediately. Many years later, when the time was right, a few people finally suggested that it was time to start, and in 2009 I was able to officially start researching the Mr. Akioka family.

― Were all the materials in one place? Or were they scattered in different places?

Furihata Initially, I went through the materials in the DOMA, where many people came and went, and in the archives at the back of the building, but I didn't know what I was looking for. Later, his eldest son, Mr. Yo Akioka, told me that he had found some wardrobe boxes in the back of his house, which had been carefully kept by Mr. Akioka's wife, and they were full of paper materials. It was full of paper documents, including children's drawings from the early days and furniture designed for the Occupation Forces. There were a lot of people coming in and out of DOMA, so his wife kept it in a safe place so that people wouldn't touch it. It is a pity that I have not been able to ask her about these documents during her lifetime, because I would have learned a lot more about them.

― He collected some 6,500 carpentry tools, but where did he keep them?

Furihata He may have kept them in DOMA, but before his death, Mr. Akioka wanted to create a "library of objects" and proposed to the town of Oketo in Hokkaido, where he gradually moved his tools to the "OKECRAFT Centre Forest Craft Museum". After his death, his bereaved family donated the remaining tools, as well as some 18,000 other items, including bamboo paddles, Nima vessels made using the Ainu method, articles he had written, and video materials. The museum has archived the materials and published a series of books called "Nihon no Teshigotodougu – Akioka Yoshio Colekushon" (OKECRAFT Centre Forest Craft Museum, 2007 - 2018). Mr. Akioka's assistant, Ms. Tomoko Masuda, moved to town of Oketo and worked as a researcher at the museum for about 11 years from 1998 to 2009, organising the material.

― So Mr. Akioka's materials are now in three places: the OKECRAFT center, the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo and his home and DOMA?

Furihata There is also a collection of materials related to Mr. Akioka at the Kumamoto Prefectural Traditional Crafts Center, which opened in 1982 in his hometown. Rather than being designed by Mr. Akioka, these are woodwork and household utensils that he collected in the late 1970s from all over the world. The building was designed by Mr. Kiyonori Kikutake, and Mr. Akioka conceived the concept of the exhibition plan, including the display of the soft parts and the drawer storage where visitors can actually touch the objects. The year after the museum opened, Mr. Akioka was a member of the jury for the "Craft of Life" exhibition. This year marks the 35th anniversary of this project.

― Are there any stored at the university where he taught?

Furihata At the Tohoku Institute of Technology, where he has been teaching since 1978, there are important prototypes from Mr. Akioka's practical research into 'Urasaku Kogei', the local craft activities he carried out in the 1980s in the village of Ono in Iwate Prefecture and the town of Oketo in Hokkaido, but their current state is not known. He also taught at Kyoritsu Women's University, but I am not aware of any archives there at the moment.

Organising the archive with the help of a grant.

― I understand that you received a research grant from the POLA ART FOUNDATION to conduct a survey of Mr. Akioka's archive.

Furihata I applied for the grant twice, in 2010 and 2011, in order to organize the works and materials found in Mr. Akioka's house and to hold an exhibition at the Meguro Museum of Art. We spent three years compiling the materials and in 2011 we held the exhibition "DOMA Yoshio Akioka Exhibition: Design of Thoughts and Relationships to Things" at the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo. The grant was used to cover the costs of photographing and organising the materials, deciphering them, taking data and measurements. There was a huge amount of material, so we gathered the staff and together we numbered and sorted it, put it in files and put it away in bags. We also received a great deal of help from Ms. Tomoko Masuda, who organised the materials from town of Oketo. She understood Mr. Akioka very well and helped us a lot.

A view of the exhibition "DOMA Yoshio Akioka Exhibition: Design of Thoughts and Relationships to Things" at the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo in 2011. The photo below shows a reproduction of Akioka's work space, which still remains in his home.

Photo courtesy of Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo, photo by Tadahisa Sakurai

― How did you classify and archive Mr. Akioka's material? Do you have any guidelines for this?

Furihata We haven't yet reached a definite archiving stage. We are gradually accepting them into the museum, sorting them into categories such as photographs, children's drawings, books and manuscripts, and storing them in boxes, but it will take some time.

In organising these materials, we have benefited from the advice of the art librarians who set up the art library of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in Ueno. They are the pioneers of art librarianship in Japan. The museum, designed by Mr. Kunio Maekawa and reopened in 1975, was the first in Japan to create an art library dealing with post-war art. The library collected mainly museum catalogues, gallery pamphlets, letters, books and other secondary materials of artists, and art librarians organized them. The young curators of the museums that opened in the late 1980s, myself included, were very much indebted to the library. Later, when the curatorial department of the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum was transferred to the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, the functions of the library were also transferred.

― What did you learn from the art librarians at that time?

Furihata The three people who have helped me so far are Mr. Masatoshi Nakajima, Ms. Tamiko Nozaki and Ms. Sachiko Kaji. They taught me how to handle art library materials and how to collect data from them. In the 1980s, the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum's exhibition catalogues, especially the artists' chronologies and bibliographies, were prepared by these librarians, and they were very accurate and comprehensive, and have become the standard for exhibition catalogues today. I think they were the first generation to archive materials in Japanese museums, and I would like to hear their stories. I think it would be very useful to hear about the methodology of how they see the materials and how they pass them on to future generations.

Set a time to do it, concentrate on it and keep it up as a habit.

― We would like to talk to them. Next year will be the third year of our Design Archive activities, and we would like to think about the next step: how to organize the archive. In our interviews, we found that people are interested in archiving their work because they don't want their footprints to be lost after their death. However, it is often the case that they keep the materials for the time being, but do not know how to organise them, so they are left in cardboard boxes in a haphazard way, which will only cause problems for future generations. When donating materials to museums and universities, some people say that it would be good if the designers could organize them in a certain way. However, there is no guideline for organizing archives in Japan, so I would like to create a place where we can all think about this in the future.

Furihata When we organized Mr. Akioka's materials, we asked art librarians for advice on how to keep the materials and data, and what kind of information we should pick up. There must have been a limit to what the designers could do on their own.

― That's true. I'm thinking of holding some kind of workshop where someone can teach us how to organise the archive.

Furihata Mr. Akioka's father, Mr. Goro Akioka, is also a great man and an important figure in the history of libraries in Japan. I think that he was a pioneer in terms of the archives that you are talking about. He made many proposals about how libraries in primary schools to universities and public libraries should be, how to show and organize materials, how to make usage fees free, how to change from closed to open shelves, and so on. During the war, he was a central figure in the "Evacuation of Rare Books Project", in which students were given books from the library to evacuate to storehouses in the countryside in order to protect them.

Mr. Akioka had a lot of materials about Mr. Gorou in his house. Mr. Kaname Matsuoka, a former secretary-general of the Japan Library Association and a long-time member of the library in Meguro Ward, who had studied Mr. Goro and published a book with his colleagues, investigated the materials of Mr. Goro again and found that they were very important materials, which were donated to the Japan Library Association. I think it will be a very valuable material for the history of libraries in Japan.

― It's also very interesting. Who else's materials are you archiving at the Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo?

Furihata Before sorting out Akioka's material, we sorted out the material of the painter Mr. Usaburo Ihara. He went to France in 1925 as an overseas trainee for the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, and during his four and a half years in Paris he kept all the papers that passed in front of him - tickets, receipts, maps - and his son, Mr. Otoaki Ihara, kept them. The Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo has accepted all of the materials. In 1997, we held an exhibition entitled "Longing to Travel: Painters on the Grand Tour", and we arranged the materials in a large frame, arranged according to category, and displayed them mainly here, with works from the museum's collection painted in France on the walls. At the end of the exhibition, we sorted the papers into categories such as life, transport, maps and entertainment, put them in boxes and numbered them.

That was the end of it at that time, but in 2017 I was able to receive a grant from the Kao Foundation for Arts and Sciences, so I hired a staff member to continue organising the materials for the first time in 20 years. We rephotographed each item and reconfirmed how to describe the data. Mr. Ihara's materials are now in order and we can show them to people who ask for them.

I think we were able to do the second one based on the fact that we had already organized the material once 20 years ago. In the meantime, 20 years have passed, and I thought it was important to take time and organize the materials patiently and steadily, because you can't do everything at once if you want to. It is better to concentrate on this kind of archiving work at a specific time, and it is also necessary to continue it habitually.

What is the appeal of Yoshio Akioka?

― What do you think about the fact that there is no design museum in Japan and no one to accept the archives?

Furihata It's a question of where and how much we accept. If we were to accept everything, it would be a big problem. I don't think any museum can afford to do so, but if the material is attractive, I think they will work on it.

― For you, it's like Mr. Akioka's materials. How did you find Mr. Akioka attractive?

Furihata When I organized Mr. Akioka's materials and saw the exhibition as a whole, I felt that it was very close to the way of thinking and living of Charles Eames and George Nelson, who were active in the American mid-century. Eames was a designer who made films and toys, organised exhibitions and was very particular about the way he saw things. George Nelson was a thinking design director who worked in architecture and design, wrote books and thought about design systems. Mr. Akioka is more like a thinking George Nelson.

― Mr. Akioka's many published books show that he was a deep thinker.

Furihata I think he always had a good grasp of the "now". Mr. Akioka had experienced the war and he had also seen enough of the industrialisation of post-war Japan's recovery period to stop doing industrial design around the time of the Osaka Expo (Japan World Exposition, Osaka) when the whole country was excited. He felt that the industrial design of that era, in Japan's period of rapid economic growth, was limited in its ability to do what designers were supposed to do. During this period, he also wrote a book titled "Waribashi kara Ka made" under the title of "A Stuck-up Industrial Designer". This was a time when the number of in-house designers was increasing rapidly, and the world was moving towards mass production and mass consumption, making it difficult for designers to make the kind of proposals they should be making to society.

― So there are as many photographs as there are books by him.

Furihata There are many photographs taken by each member of KAK, the industrial design firm he started in 1953. There is no indication of who took the photographs or the year, but as I researched, I gradually came to understand that the photographs were taken around this time. As you can see from the photos, the way the KAK design office works is very interesting. Everyone seems to enjoy working and playing together. Mr. Junnosuke Kawa, one of the founders of KAK, has many photos of himself building sailing boats, but he also did a lot of very precise design work. It is also interesting to see how he was always proposing new ideas to companies and thinking through communication. I think these photos are a valuable insight into post-war Japanese industrial design in the 50s and 60s.

Exhibitions can be a good opportunity to organise your material.

― Do you have any drawings of their industrial products from the KAK era?

Furihata No, I haven't found any yet. I have some photos of him drawing, but I would like to see them if they exist somewhere. By the way, it's also interesting to know how Mr. Akioka saw Mingei.

― That's something I really wanted to ask you about. During the post-war period of Japan's reconstruction and rapid economic growth, mechanisation replaced handwork, and the relationship between maker and user and people's life skills were lost. In the midst of this, he advocated "stop consuming and become a user", and his emphasis on the importance of making things by hand seems to overlap with the idea of Mingei.

Furihata People say that Mr. Akioka is a craftsman who values handwork, but in fact he thought it was important to maintain a balance between handwork and industrialisation. He said that it is not necessary to do everything by hand, but that it is okay to industrialise what can be done, but that it is important that hands are involved at the end.

I also think about what Mr. Akioka would be like if he were alive today. I wonder what he would think about this internet society, and whether he would use it in his own way.

― I would like to ask him about it. Do you still continue to research and organise his materials?

Furihata It's been eight years since the exhibition, and I haven't had much time since then, but I'm working on it little by little.

― Now that you have sorted out Mr. Akioka's materials, what do you think about the future of the archive?

Furihata I would like to continue organising the materials and interviewing the people involved. Exhibitions are a great opportunity to concentrate on organising the material, and I hope to hold another exhibition of Mr. Akioka's work in a few years time.

― We would be delighted to talk to you again about his archive. Thank you for your time today.

Enquiry:

Meguro Museum of Art, Tokyo

http://mmat.jp

OKECRAFT Centre Forest Craft Museum

http://okecraft.or.jp

monomono

https://monomono.jp

Kumamoto Prefectural Traditional Crafts Center

http://kumamoto-kougeikan.jp