Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Shin Matsunaga

Graphic Designer, Art Director

Date: 31 October 2017 14:00 - 16:30

Location: Shin Matsunaga Design Office

Interviewees: Shin Matsunaga, Shinjiro Matsunaga

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Shin Matsunaga

Graphic Designer, Art Director

1940 Born in Tokyo.

1945 Evacuated from Takanawa, Tokyo to Chikuho, Fukuoka due to the Second World War.

1964 Graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Design.

1971 After working in the advertising department of Shiseido, established Shin Matsunaga Design Office.

Special Prize at JAAC, Tokyo ADC Award, Mainichi Design Award, Gold Prize and Honorary Prize at the Warsaw International Poster Biennale, Minister of Education's Art Encouragement Prize, Japan Advertising Award, Yamana Prize, New York ADC Award, Medal with Purple Ribbon, Yusaku Kamekura Award, Hiromu Hara Award, etc.

Description

Description

Shin Matsunaga's design is symbolized by his creed, "the idea of a three-metre radius". The famous Ikko Tanaka described as follows: "It is an expression of his confidence that 'life' is the basis of his work. In fact, it is an expression of his confidence that 'life' is firmly rooted in the foundation of his 'work', and the simple and straightforward ideal that life is seen through the eyes of society and extends to the world is in fact the backbone of Shin Matsunaga".

Yusaku Kamekura also commented: "This is a man whose design is the result of his own humanity. I think this is a person whose design is a direct result of his own humanity. I think he was able to do this because he is a strong person who perseveres in his efforts to maintain his beliefs. Matsunaga's design is truly 'the aesthetics of everyday life'". It is no coincidence that two of the leading graphic designers of the post-war period have found the essence of Matsunaga's design in "ordinariness" and "life".

20 Starting at the beginning of the 20th century, modern design has developed in step with technological innovation, aiming to "enrich people's lives". At the same time, it was a new stage for designers to express their individuality and creativity. In the world of Japanese graphic design, Hiromu Hara, Yusaku Kamekura, Ikko Tanaka, and others created works with a strong sense of authorship that were highly regarded and led the design world. In this context, Matsunaga was the first designer to establish a firm position in the field of anonymous design that blends into everyday life.

At the same time, Matsunaga continues his creative activities, which he calls "Freaks". The word "Freaks" means impulse, whimsy and drunkenness. In his atelier, which is a different space from his main office, he is immersed in his work with the energy of a child. It's a world of freedom where he can express and create according to his inner passions, as opposed to the simplicity and rigour of client-commissioned design. By moving between these two worlds, Matsunaga's design and freaks' creations, which at first glance seem to be complete opposites, are fostered.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

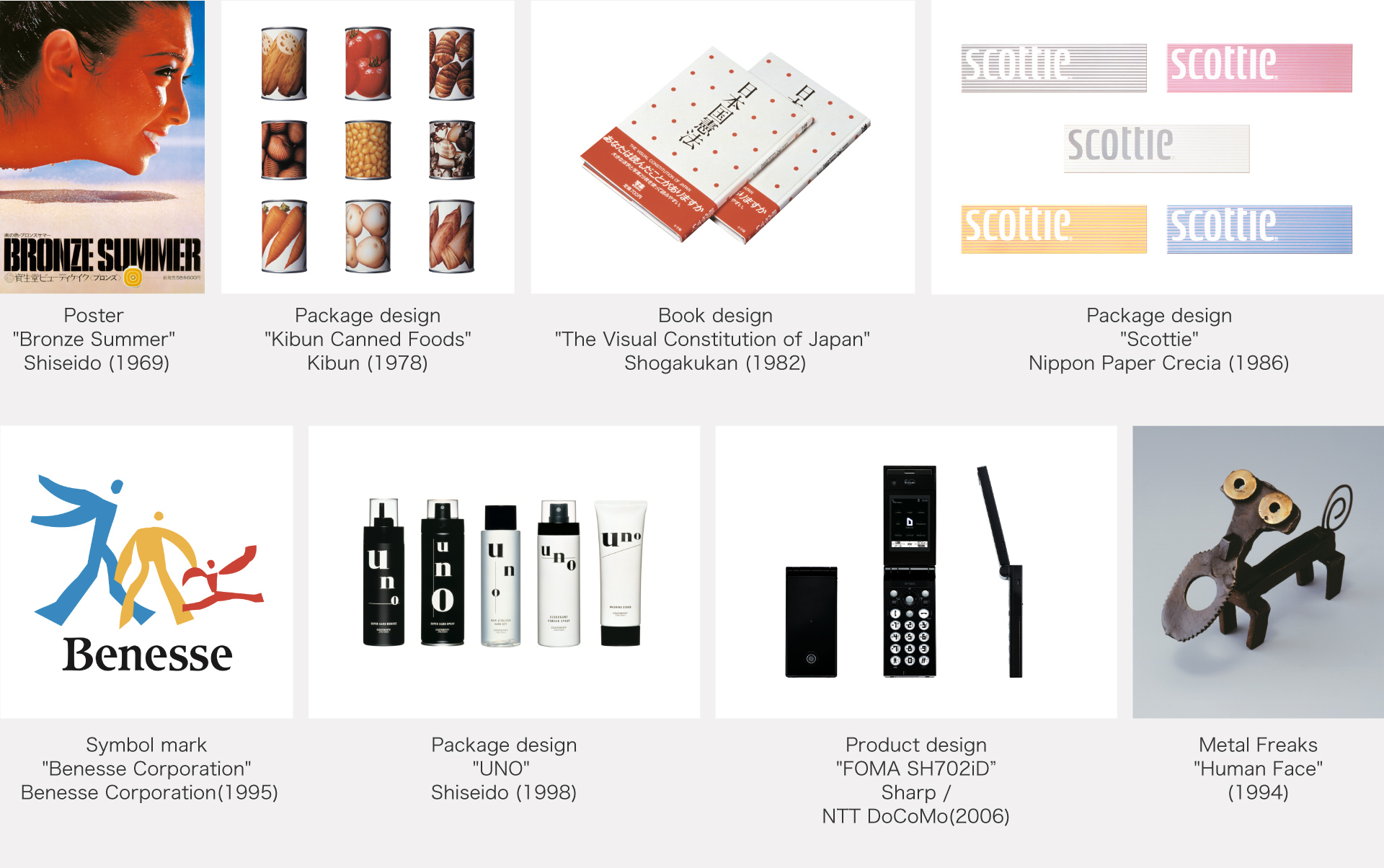

Shiseido Beauty Cake "Bronze Summer" Shiseido (1969); Shiseido Sun Oil "People, People, People" Shiseido (1971); "Kibun Canned Foods " Kibun (1978); "The Visua Constitution of Japan", Shogakukan (1982); "Scottie" Nippon Paper Crecia (1986); PEACE "Love, Peace and Happiness" Poster (1986); ISSEY MIYAKE Symbol Logo (1989); "Calbee" Symbol logo (1994); "Benesse Corporation" Symbol Mark (1995); "UNO" Shiseido (1998); "JAPAN" poster (2001); National Museum of Western Art symbol mark (2004); "ISSIMBOW" Nippon Kodo (2005); "FOMA SH702iD" Sharp / NTT DOCOMO(2006); Poster for "HIROSHIMA APPEALS 2007" Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation / Japan Graphic Design Association (2007)

Books

"The Design of Shin Matsunaga" Kodansha (1992); "Graphic Cosmos: The World of Shin Matsunaga", Shueisha (1996); "Shin Matsunaga, The Story of Design", Agosto (2000); " Talk about Designing by Shin Matsunaga +11", BNN Shinsha (2004); "ggg Books special Edition -9 Shin Matsunaga", DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion (2013)

Interview

Interview

We are concerned about the current situation where design is consumed as information

The source of true Matsunaga‘s design

― Mr. Matsunaga has been working as a graphic designer for more than 50 years after graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts. During this time, you have created many posters, CI, packaging for daily necessities, products such as mobile phones, and have been searching for universal designs that are closely related to people's lives in today's rapidly changing world. This is work that should be preserved as an archive for the future of design.

Recently, your son Shinjiro has been organising your works and documents, and they are now in the collections of several 88 museums in Japan and abroad, including the Tagawa Museum of Art in Fukuoka, where you spent his childhood, the Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA) and the National Museum of Modern Art,Tokyo (MOMAT).Today we would like to ask you about your thoughts on design archives.

Matsunaga If you say that my work is suitable for the archive, I would like to tell you about the source of my design first.

My work is concerned with the whole range of graphics that shape our living environment, as summed up in the phrases "all of life is design" and " idea of a three-metre radius". In this sense, winning the Mainichi Design Award in 1987 was a big event for me. Before that, big projects such as architecture, cars and fashion had been the mainstream, and there had never been an award for the design of anonymous everyday items such as tissue paper or the packaging for Can chu-hi . I was very surprised to receive this award and it was a big push for me.

― It's true that before you, the mainstream was dominated by artists such as Yusaku Kamekura and Ikko Tanaka. What prompted you to explore the possibilities of design beyond that?

Matsunaga I spent a lot of my childhood in Chikuho, Fukuoka Prefecture. I was originally born in Tokyo and lived in Shirogane. However, at the end of the Pacific War, my father, who was a calligrapher, escaped the air raids on Tokyo and evacuated the family to Kyushu, where I lived from childhood until the middle of junior high school. At that time, Chikuho was a thriving coal industry. People from all walks of life lived in the small area, from the elite of the Mitsui Mine to the blackened miners, and all the children went to the same school. There were children from elite families with grand pianos and art collections at home, and there were children from poor families who were able to study but had to give up their education. My family was not rich, but we had a cultural life with a gramophone that my father brought from Tokyo and a French 9mm film projector.

― Was there a moment in your childhood when you discovered your talent as a designer?

Matsunaga I've always been a good painter, and I've won awards in drawing competitions, and I've made name tags for my classmates.

― Is it a name tag?

Matsunaga All primary schools students wear the same name tag, but each student is different. I used to make name badges for my classmates, which became so popular that other classes asked me to make them for them. I also won many prizes at school and district cultural events and competitions. When I graduated, the headmaster made the school's first "Cultural Merit Award" for me, and my father, a calligrapher, was bewildered when the headmaster asked him to write the certificate of commendation.

― I have the impression that your work always expresses timeless and universal values, from corporate logos, everyday product packagings and the Hiroshima Appeals poster to works with a strong social message. They have the power to appeal to the senses shared by all people, young and old, men and women, regardless of nationality or culture. I believe that this sense was nurtured by spending a pure childhood in the unique society of Chikuho, catching glimpses of the absurdities and contradictions of society as a child, and experiencing the people who live strongly despite such circumstances. Mr. Matsunaga, you have said that "this reality that I experienced as a boy became a very big backbone for me as a designer". After that, you spent your junior and senior high school years in Kyoto and went on to study at Tokyo University of the Arts.

Matsunaga At Tokyo University of the Arts, we had many excellent classmates, such as the designer Motomi Kawakami, Fujio Ishimoto who worked for Marimekko, and the picture book author Kazuo Iwamura. We were the only students in our class who were required to study not only design, but also lacquerware, metal carving and dyeing. I was puzzled as to why I was studying graphic design and not metal engraving. But in the end, I was very fortunate because I was able to study directly under the guidance of an artist who was a living national treasure. In hindsight, I think that something I gained from the opportunity to experience traditional crafts has influenced my subsequent work.

― So you were able to learn the attitude to manufacturing, the way of perceiving things, the knowledge and wisdom that cannot be obtained only by studying design. And after graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts, you worked in the Shiseido Advertising Department for seven years before setting up your own business?

Matsunaga I was born in Tokyo, moved to Kyushu as a child, moved to Kyoto in junior high school, came back to Tokyo, went to Tokyo University of the Arts and then to the advertising department of Shiseido. In other words, my relationship with Shiseido before and after the age of 18 is deeply connected, and has been a great source of inspiration for me.

About the Design Archive

― We understand that you have a considerable amount of work and materials spanning 50 years. I understand that your son Shinjiro is currently leading the work.

Matsunaga It is more than 50 years, so the amount of work is enormous. In my case, when I was in my 20s, I was just starting out as a designer and the amount of work was still small. However, in my thirties and later, I was too busy to keep up with the increasing number of documents that accompanied my work. So I have to leave it to my assistants of the past generations, who, depending on their personalities and qualities, are in a different state of organisation and preservation. They can't make decisions about which materials to keep and which to dispose of. Only I and my relatives can be responsible for this part of the work, so at present my son and my wife are taking the lead.

― So organising the materials is a secondary task. Many of the people who have helped us with this research have told us that, like you, they find it difficult to do it themselves.

Matsunaga Yes, it is. I'm not able to do much myself. I think I am putting a lot of pressure on my son and my wife.

― How exactly is it archived?

Matsunaga The first step I do is to get rid of things I don't need. I have a huge number of books and other publications that I have worked on, printed materials that I keep in case they might be useful, and letters of commendation that I have received in the past. I put them away every day. I don't have a hobby of framing and displaying all the awards. However, someone is getting me things I want to get rid of, so that helps me a lot.

I used to keep my work in Terada Warehouse, but now I keep it in three separate places: my office, my studio and the basement of my house. This building (the office) was designed by Ikuyo Mitsuhashi and has a lot of storage space, so I keep my Freaks' work in this basement. For a while we had an office in Tokyo Opera City and rented a warehouse in the basement, paying a huge rent per month, but we decided that it would be better to have our own space for the future. I think that's when I started to think about the idea of an archive.

Shinjiro Matsunaga Specifically, the collection is stored by category, including posters, packaging, book design, drawings and bronzes. The information on the works, such as title, year of production, size, category, client, etc., is stored in a FileMaker database together with the images of the works, and can be searched by location, number of works stored, and collection destination. The information on the progress of each project is also filed, organised and stored.

― How are the actual posters and other materials stored?

Shinjiro As for the poster works, the full size B posters are stored in a special cabinet, while the B0 posters are rolled up and placed in a storage case on a special shelf. The smaller sizes are kept for a certain period of time and, unfortunately, are eventually disposed of. The packaged works are stored in boxes or other containers for each project. For example, the tissue paper 'Scottie' has undergone several renewals since 1986, and we keep these so that we can trace the process and improvements. Takara Shuzo's Can chu-hi has also been redesigned several times since the original design, and the range has increased, but we have kept all the main designs.

Graphic design is a duplicate product, so some of the best-known works, posters for example, have only a few copies left, while some relatively new works have dozens of copies. Nevertheless, storage space is limited, so the stock needs to be sorted out on a regular basis, which is quite a task.

Matsunaga What I do in terms of organising my materials is to rank my work in ABCs and decide which ones to keep. I wish I could keep everything, but space is limited and I have to decide which to keep. It would be nice if we could keep all of them, but we have to choose which ones to keep. In the part about Professor Kamekura in this archive survey, there is a description of how he had disposed of all his notes, but his staff, who regretted it, picked them up from the trash and kept them. When I read that sentence, I thought the same thing.

― So what about articles in magazines and newspapers?

Shinjiro We keep the original copies of all the newspapers, magazines and catalogues. We also file photocopies of the published pages and use a Claris FileMaker to create a database so that we can search by date of publication, name of the newspaper or magazine, title of the article, etc.

― You are showing us a large archive of posters and books in the basement of your office, but do you also have a similar archive in the basement of your home and studio?

Shinjiro In the basement of our studio we keep mainly posters and packaging. In the basement of his house he keeps a collection of his own works, drawings and bronzes.

― This is the first time I have seen such a well organised archive. The database that Shinjiro-san has created is also very informative, with information on the collections and their numbers. It's very easy to find out what's where. It's a lot of work to organise and store the objects, but it's even more work to input this data.

Shinjiro The database compilation started around 2000. It took a long time because it was created from scratch. We start inputting with the main poster work, gradually increasing the categories and then adding more as new work is completed. But I don't think it means anything if I simply organise and store them in our office or home. I believe that it is only when the works are stored in a public institution, such as a museum or university, and are used effectively, that they have value as an archive. However, finding recipients for these works is a very difficult task.

Matsunaga The problem is where to go with the materials that we spend so much time and effort organising and storing. In my case, I am sure that my wife and children will be able to protect them, but I do not know what will happen to my grandchildren's generation.

― In your case, your posters are in the collections of relatively many public institutions, such as DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion, Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art and Design, Musashino Art University Museum and Library, as well as some museums in Germany, France and the USA.

Matsunaga Posters are flat and relatively easy to store. It is also easy to hold an exhibition because it has a strong artist and message, and I think museums find it attractive as an object of collection. However, my work is not limited to posters, and I think it would be good if there were places that would carefully archive and make use of other types of design.

― When I was researching the collection of Matsunaga's works, I came to know that they were collected together in the Tagawa Museum of Art in Fukuoka, where you spent your childhood. How did you come to know about it?

Matsunaga As I mentioned at the beginning, I was evacuated to Chikuho, and when the first museum was opened in Tagawa, I designed and donated the symbol mark and logotype as a way of repaying the kindness of my boyhood. In addition, to celebrate the opening of the museum, an exhibition entitled 'The World of Shin Matsunaga Design' was held, and the works exhibited at that time were donated to the museum as they were.

What a design archive should look like

― We would like to ask you what you think about design archives and design museums.

Matsunaga I would like to keep my own archive. Fortunately, in my case, my son takes care of organising my works and documents, for which I am grateful. When I tell people about this, they say, "It's nice that your son is taking over", but there is no such thing as a creative successor. I don't think he even thinks about it.

― Nevertheless, we are very fortunate that our relatives are working on the archive.

Matsunaga As I said earlier, it is very difficult for an individual, such as a family member, to preserve and pass on an archive. I think it is better to preserve them in a public institution such as a museum or a university.

We are in the process of preparing an exhibition for the German Poster Museum, and we hope to donate the work as it is. The work is already in the collection of the museums in Munich and Hamburg, but we have a feeling of trust and confidence that Germany will preserve the work properly. We are currently working with the museum on the arrangements. But this is only part of my job.

― It is true that the donation of works for an exhibition does not include all the works. However, if a group of works based on a certain theme can be made into an archive, it would be possible to convey Matsunaga's message clearly.

Matsunaga It would be fortunate to have an archive in this form as well.

― Mr. Matsunaga does a lot of work for companies and organisations, such as packaging and CI, but there is no movement for clients to archive product-related design as part of their cultural activities.

Matsunaga Unfortunately, it seems that there are not many companies in Japan that manage and store their own products and design materials. I feel that it is difficult for companies and organisations to connect their design ideas, as the person or department in charge may change. For example, in many companies, the design history of long-selling products such as " Can chu-hi" is not stored properly, and when needed, designers often have to refer to the materials they have. In the past, even Shiseido did not have a complete archive, and there were times when Eiko Ishioka and I provided our own posters and other materials from the Shiseido era for exhibitions.

― With such fast changing times and product cycles, it is becoming more and more difficult to find the origin of a design and to trace the process of change. I strongly feel that design archives have an important meaning, not only for the results, but also for re-examining the era by recording and tracing the background of the design and the process of change.

Matsunaga I have a question on the other hand, where is the goal of this "Survey of Japanese Design Archives"? Because I myself am working on organising my own work and documents, but I don't know what will happen afterwards. It is impossible for a single company to carry out such activities, and even so, in the current situation in Japan, it seems difficult for the state or the government to create a design museum, and we can hardly expect it.

― You are right. We are only a small NPO, so we can't build a design museum. But as the generation of people who have created Japanese design is changing, their works and materials are being lost. Once they are lost, they can never be recovered. That's why we believe it is important to hear about the current situation and record it. For example, if someone want to hold an exhibition, it is important to know where the works and materials are, who manages them, and what condition they are in. We are working on this, hoping that in the future we will be able to collaborate with similar people and organisations.

Matsunaga One thing that has been bothering me lately is the disappearance of so-called design journals. If someone just want to get information, the web may be fine, but I believe that life itself is design, so I am worried about the current situation where design is consumed as information. I think the journal is significant as a place to think and talk about the meaning and background of design. From the point of view of a design archive, the existence of a design journal should be significant.

― That's right. But in terms of design archives, little by little there are organisations, groups and individuals who are starting to focus on archives. Even if it is difficult to build a national design museum, a network of small design archives could be a new form of museum. I would like to explore the possibility of working with such an organisation. Thank you very much for your time today.

Enquiry:

Shin Matsunaga Design Office

Tel: 03-5225-0777

Fax: 03-5266-5600