Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

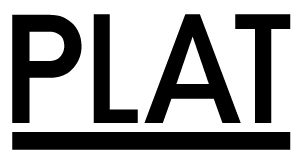

Makoto Komatsu

Product designer

Date: 2 November 2023, 14:00-16:00

Location: Komatsu Studio

Interviewees: Makoto Komatsu

Interviewers: Aia Urakawa

Writing: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Makoto Komatsu

Product designer

1943 Born in Tokyo

1965 Graduated from Musashino Junior College of Art, Department of Crafts Design

1965-69 Worked in the laboratory of the Craft Design Department at Musashino Art University

1967 Awarded the Grand Prix at the Craft Exhibition of the Japan Craft Design Association

1970-73 Worked as Stig Lindberg's assistant in the design department of GUSTAVSBERG in Sweden

1973 Returns to Japan and establishes Komatsu Studio

1975 Formed the design group FAM Product

1980 Awarded the Kitarou Kunii Craft Industry Awards

1986 Awarded the Grand Prix at the 1st International Ceramics Festival MINO'86 in the design category

Awarded the Grand Prix at the 30th Ceramics Design Competition

1999-2013 Professor at Musashino Art University, Department of Crafts and Industrial Design

Museums, universities, etc. where the works are held

Museum of Modern Art, New York (MoMA, USA), Corning Museum of Glass (USA), Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (Canada), Canadian Museum of History (Canada), Victoria and Albert Museum (UK), Hamburger Kunsthalle (Germany), International Museum of Ceramic, Faenza (Italy) Cantonal Museum of Fine Arts, Lausanne (Switzerland), International Coffee Cup Museum (Finland), National Art Museum of China (China), Shanghai Museum of Arts and Crafts (China), World Ceramics Expo Foundation (South Korea), National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Ibaraki Ceramic Art Museum, Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, Gifu, China Academy of Arts (China), Kangnam University (South Korea), J.E.P University, faculty Art and Design (Czech Republic), Aichi University of the Arts, Musashino Art University, Museum of Contemporary Ceramic Art, Shiga, Ishikawa Prefectural Institute for Kutani Pottery, etc.

Description

Description

Makoto Komatsu is a product designer working in the field of craft design. He works with ceramic, glass, stone, aluminium and other materials on the subject of objects used in daily life. He has produced a number of blockbuster pieces, which are in numerous collections at museums and universities around the country.

When Komatsu was in high school, he was inspired by the vessels in the Scandinavian design section of a department store, and enrolled in university to study ceramics in the Crafts and Design Department. In the 1950s, the Japanese design world was at its dawn and there was a great swell of activity. In the field of products, crafts were born, rooted in a new way of thinking about making things that differed from folk art and traditional crafts. It is a design for use in everyday life that enriches our lives, where repetitive production is possible while facing the materials and rediscovering the charm of handwork. In 1956, the Japan Designer and Craftsman Association (renamed the Japan Craft Design Association in 1976, dissolved in 2021) was established and craft corners were set up in department stores.

Komatsu went on to pursue his craft design career. After graduating from university, he studied under Stig Lindberg in Sweden, and after returning to Japan, he set up his own studio in 1973, where he created a wide variety of works, demonstrating his abundant individuality and talent. Komatsu's name became most widely known with the "Crinkle series". These vessels were made using wrinkles as a motif, focusing on the patterns on the plaster used to make the moulds for the pieces. The series became an explosive hit when it appeared in a magazine and has been a long-life product since its launch in 1975. It was selected for the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York and the Victoria and Albert Museum.

He is still active at the age of 80, and this year he presented two new products from Ceramic Japan, which celebrated its 50th anniversary. One is two types of earthenware bottles and teacups named "TORI" and "YAGI". He inherited the ancient history of animal-shaped vessels being made and designed the spouts of the earthenware bottles with humorous and adorable bird and goat faces, respectively. The other is a white porcelain vase for a single flower that looks like a single tube that is turned around and tied together. The name of the work is "MUSUBU", which evokes auspicious words such as "to make a connection" and "to bear fruit". They were exhibited at the Interior Lifestyle Tokyo 2023 international trade fair held at Tokyo Big Sight in June this year, where they stood out amongst the many works on display.

They are used and appreciated by many people in Japan and abroad, and have an irresistible appeal. I visited the his studio where such works are produced and spoke to the artist about his thoughts on Lindberg, the background to the creation of his masterpieces and his thoughts on archiving.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

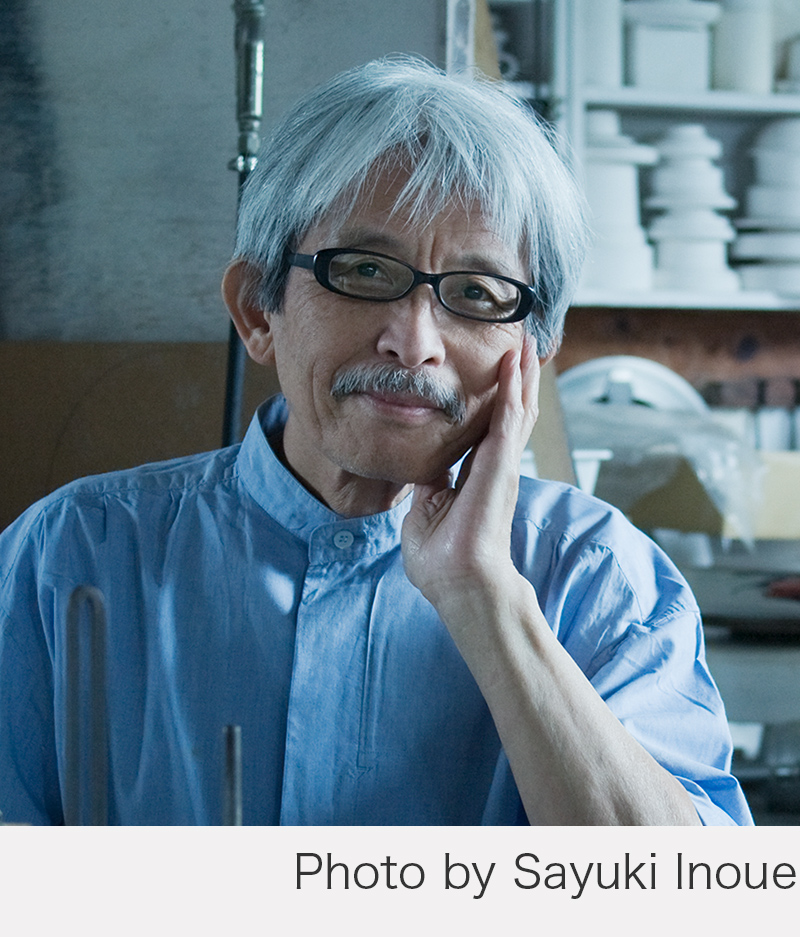

Vases (1964); lighting fixtures (1964); candlesticks (1964); ceramic objects (1967); tea vases (1969); ashtray "KUL", Ceramic Japan (1974); "Kneaded glass" (1975); "Hand series: mugs, vases" (1975); " Crinkle series: tumblers, super bags, glasses, plates, clocks, coffee cups, objects, lamps, plates, vases, Everest, mini Everest, etc ", Ceramic Japan, Komatsu Studio (1975-); "Wall tiles" (1975); "SQ seasoning set", Ceramic Japan (1976); "Toiletries" (1977); "Photo Frame", Ceramic Japan (1978); "Crumple Series: porcelain, pappel, tumblers, wine glasses, plates, etc ", Kimura Glass (1979-); "Seasoning Pouring Vessel" (1980); "Stone Cup" (1981); "Stone Candlestick" (1981); "Egg" (1982); "Flat dish" (1983); "Earthenware pot" (1984); "MAARU decanter, brandy glass", Kimura Glass (1984); "Infinity series: bowl, mug, coffee cup & saucer, etc", Ceramic Japan (1984-); "Stone Calendar" (1985); "Mimizuku" lighting (1985); "Lacquer Cup" (1985); "POTS", Ceramic Japan (1986); "SOYUSHI" door handle, Toyo Shutter OHS Division (1986); "Ovenware", Ceramic Japan (1987); "Coffee Cup" ( 1987); "Cup Kit", Kimura Glass (1987); "Q Flower Vase" (1987), "TANGO Flower Vase", Kimura Glass (1987); "ARCH Flower Vase", Toyo Shutter OHS Division (1987); "Coaster", Takenaka Corporation (1989); "Crinkle Series Super Bag (Aluminium) ", Takenaka Corporation (1989); Door Handle "SPIN", Toyo Shutter OHS Division (1989); "Hot Cooker", Ceramic Japan (1990); "Cutlery", Kimura Glass (1990); "Fossil Series: TSUNO, Kareki Hanasakajijii" (1991); "You-ki: Tokuri, Guinomi, Mug Cup, Shoyu Jar, etc", Ceramic Japan, Komatsu Studio (1993-); "Tea pot", Ceramic Japan (1994); "Stool" (1994); "Dali's elephant" (1995); "Leaf plate", Ceramic Japan (1995); "TETRA flower vase" (1996); "BALLOOON", Kimura Glass (1997); "Skull' (1998); "CERATIUM Flower Vase" (1999); "Tea Vessels" (2000); "Doki-Doki Clock" (2000); "CWVG" (2002); "KUU Series: cups, plates, bowls, soy sauce jugs, etc" (2002-); "Shari-ware" (2003); "Triangle", Kimura Glass (2006); "Dressing Pot" Kimura Glass (2006); "Tea Vessels" (2007); "Homage to Magritte" (2008); "ROOTS Flower Vase" (2008); "Talking Cup", Ceramic Japan (2008); "Wall Vase" (2009); "Branch Chopstick Rest" (2010); "Lacquerware", Joboji Lacquerware (2011); "Flower Vases" (2012); "Plus Minus Decoration" (2015); "Neo+ Series: glasses, gulps and vases", Kimura Glass, Komatsu Studio (2015)

*Except as noted, manufactured by Komatsu Studio.

Books

"Makoto Komatsu exhibition : design + humour",(National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, 2008); "Tōji : hassō to shuhō" (Co-author, Musashino Art University Press, 2009); "Komatsu no hon-1943"(ADP, 2012)

Interview

Interview

I have a strong desire to bequeath my books to future generations,

I hope it will help someone or something

Discovered the world of design as a high school student

ー We also want to preserve the designers' ideas about design and their work for future generations, and we would like to ask you about this. We would like to start by asking you how you became interested in design.

Komatsu Looking back, it may have been my mother who first showed me this path, telling me that there was a way out. I am the youngest of three siblings and I was the only one who was not good at studying and was a dropout, so I think my mother was having trouble deciding what path to take me on. My mother liked to draw and make things, and she was very good at it. Perhaps I inherited her DNA, but I also liked arts and crafts since I was a child. So I guess I thought that she would probably be good at this kind of thing. So she consulted someone called Ms. M. She was a Canadian-born Japanese who returned to Japan at the outbreak of war between Japan and the USA in 1941 and was fluent in English. I don't know the details of how they knew each other, but I think Ms. M was bullied because that's how she came from. It was during the war. So my mother covered for her and took care of her in various ways. After the war, Ms. M accompanied the staff of the Industrial Arts Institute on a tour of the USA as an interpreter, where she met the designer Mr. Shogoro Terashima, who introduced me to his design office.

It was in the early sixties, during my senior year of high school, when I was thinking about going to university. That's when I first encountered the world of design. At Mr. Terashima's office, I borrowed foreign design magazines and a translated copy of American designer Raymond Loewy's "From Lipstick to Locomotives", which I was allowed to read.

ー Did you work part-time in Mr. Terashima's office?

Komatsu No, it was not a part-time job, but Mr. Terashima told me to come and visit him once a week, and each time I was given an assignment, which he critiqued when I brought it in the following week. What I remember most from the assignments was making a spoon out of plaster. I remember that he praised me for it. He taught me that everything that exists in the world is subject to design.

ー At the time, the Scandinavian design tableware you saw at the SEIBU Ikebukuro flagship shop was one of the things that made you interested in this career path.

Komatsu When I was in high school, I was quite twisted. I used to take days off school to go to the movies and buy cheap antiques at antique shops. It was at that time that the Scandinavian Design Corner was opened in the SEIBU Ikebukuro flagship shop. It was around the time when Scandinavian design was beginning to be introduced to Japan, and there were tableware from Sweden, Finland and Denmark. However, Scandinavian design was not well known at the time and there were not many customers, so I went there every day and thoroughly enjoyed myself. I think it was also good that, unlike in a museum, I could hold the items in my hands because they were on sale. I was most interested in Stig Lindberg's tableware, which was the first time I had heard of the name Lindberg. It was totally different from Japanese pottery and antiques. The shapes were interesting and humorous, and yet they could be used in everyday life, which was just fascinating.

At that time, just after the war, Japan was in the age of imitations. Pottery and other things were made by imitating things from overseas, and these sold like hotcakes. I It's a strange thing because you imitate it, but also modify it in various ways. The market was full of such things. So when I saw Scandinavian-designed tableware in that context, I was impressed. I thought, "There is a world like this". That's how I got into the world of ceramics.

ー After graduating from high school, you entered the Junior College of Crafts and Design at Musashino Art University and majored in ceramics.

Komatsu At that time, most aspiring designers aimed to study at the Tokyo University of the Arts. But I took time off school to go and look at Scandinavian design tableware, and I didn't study much, so I didn't get in and I had to take one more exam. My family wasn't that wealthy, so I couldn't go through a lot of exams, so the only design university I could take the next time I applied was Musashi Art Junior College. In 1962, I was able to slip into its Crafts and Design Department. Once there, I found that university life was a paradise, not only in terms of the classes, but also because it was so much fun. It was a newly established university and all the teachers were graduates of the Tokyo University of the Arts and young people who had studied design abroad in Italy and Scandinavia, which were popular at the time. The students were interesting, ranging from young current students to those who had completed four years of study at the University of the Arts.

ー I understand that Mr. Tatsumi Kato, who was engaged in production at ARABIA, a Finnish ceramics manufacturer, also taught there.

Komatsu Mr. Kato studied at the Danish National School of Arts and Crafts in 1956, and was invited by Kaj Franc of Finland to work in ARABIA for a year in 1958. I have heard that he held a solo exhibition there, which was very well received. His father is Mr. Hajime Kato, a living national treasure potter. In my second year, I advanced to the ceramics course, and my first piece was an egg-shaped vase, which Mr. Kato liked and gave me a glaze to complete. I thought I did a good job, and I still keep it in a safe place.

Studied under Stig Lindberg in Sweden

ー What led you to go to Sweden after graduating from junior college?

Komatsu After I graduated from junior college, from 1965 I remained in the laboratory as an assistant and devoted myself to creative activities. However, the student movement became more and more violent and school blockades occurred everywhere. Musashino Art University was also in the middle of this movement, so I had no choice but to quit my position as an assistant in the laboratory. After I left, I remembered how impressed I was with Lindberg's tableware when I was in high school, and the idea of working for Lindberg came to me. I made a portfolio and wrote a letter to Ms. M. After some correspondence, he replied that he would hire me as an assistant. So in 1970 I joined the GUSTAVSBERG Pottery near Stockholm as Lindberg's assistant.

ー In the 60s and 70s, there were a lot of people going to Scandinavia and Italy in the Japanese design world.

Komatsu At the time, not only Scandinavian design was popular, but also colourful, figuratively free Italian modern design. Around me, too, there was a divide between those who went to Scandinavia and those who went to Italy. Around that time, the book "Seinen wa Kouya o mezasu" (written by Hiroyuki Itsuki, BUNGEISHUNJU, 1967) was also very popular. It is about a 20-year-old man who travels from Japan to Europe to become a jazz musician, and there were many young people who were inspired by this book to travel to Europe on the Trans-Siberian Railway. I travelled by train from Nakhodka, Russia, to Khabarovsk, then flew to Europe by plane and took another train to Sweden. The planes were unique propeller-driven airliners with a lot of vibration. That route was actually the cheapest. It is surprisingly expensive to travel to Europe only by the Trans-Siberian Railway, because of the cost of tickets, food and drink.

ー What kind of person or strict person were you while you worked with Mr. Lindberg?

Komatsu No, he was not harsh. I never got angry with him. He was a man of many talents, curious about many things and never sat still. I think he is a dexterous person. In his work, he never told me what to do in detail, but only said, "You have to create something that no one else has created". He strongly told me that originality is important and that my work should not resemble someone else's work. If he felt that something someone had created looked like something by someone else, he would critique it and say, "It looks a bit like that one".

ー Are there any technical differences between GUSTAVSBERG Pottery and Japan?

Komatsu I don't think it is very different from Japan, but in the world of Japanese pottery, there are various taboos and rules that say you must not do this. For example, depending on the place, you are not allowed to put knives into clay, or you have to use tools made of soft materials such as shaved wood. At GUSTAVSBERG, there are no taboos or rules of any kind, and there is a relaxed atmosphere where you can do whatever you want as long as you can make something interesting. I felt that was different.

I also thought again that Japan is a country of clay, and each region has its own unique clay, such as Mino ware, Mashiko ware and Tobe ware, which is used to make pottery. In Sweden, there is no such local clay, and various clays from abroad are bought and mixed together. There are also many pottery manufacturers in Sweden, the largest of which is GUSTAVSBERG, but there are also many older companies such as Rörstrand and Höganäs. There are also many glass manufacturers, such as KOSTA BODA, Orrefors, SKRUF and Reijmyre.

ー What was your reason for returning home after working at the GUSTAVSBERG pottery for three years?

Komatsu Before I went, I thought that if I could do the job properly, I could stay for a long time, but the language barrier was high. I don't even speak English, but Swedish was even more difficult. Wages are high in Scandinavia, so people come from many different countries to work here. People from Finland, Italy, Romania, Russian-speaking countries, etc. When I was there, there were 22 nationalities working at the GUSTAVSBERG Pottery factory. After work, Swedish language classes were held in the company, where I learned together with everyone else, and I managed to learn everyday conversation, but I didn't develop any further. Swedish is a language with vowels between "a" and "e" and between "a" and "o", in addition to "a, i, u, e, o". I could neither pronounce them nor hear them well. I think being able to do languages is a kind of talent.

ー At that time, were there any other Japanese nationals working for you?

Komatsu A number of designers had studios in GUSTAVSBERG, including Ms. Lisa Larson, a popular Japanese designer, and a Japanese woman worked for her. I did not meet her before I went there.

On representative works that have become blockbusters

ー You designed the studio yourself when you returned to Japan and opened it in 1973.

Komatsu I didn't so much design it as build it, but my wife's parents own a noodle factory and I was allowed to build it next to their house. I drew a simple plan on graph paper and asked an architect I know to build it for me. It's a simple building.

I thought about it when I was in Sweden and decided to make it when I returned to Japan, and the first work I produced at the workshop was the porcelain "Hand series". I was lucky enough to have a solo exhibition at the Craft Gallery in Matsuya Ginza to showcase my work. The exhibition was well received and sold well. Around the time I was making them for a while, industrial designer Mr. Yoshio Akioka formed the Group "monomono" with volunteers. In the 70s and 80s, he was involved in the "Stop being a consumer and start being a user" in the 70s and 80s, he was involved in a design movement in various parts of Japan to restore the original relationship between makers and users.

The movement of Mr. Akioka and his colleagues was very inspiring and influential for me. I also formed a design group called "FAM Product" with my close friends who graduated from Musashino Art University. The four of us - glass artist Mr. Hidetoshi Nozawa, textile designer Ms. Chihaya Nakagawa and her husband, filmmaker Mr. Kunihiko Nakagawa - got together to do something interesting and started working in a rented apartment in Sendagaya. We did everything ourselves, from design to production and distribution.

ー It's a group of people from a diverse range of fields.

Komatsu Yes, that's right. Mr. Kunihiko Nakagawa has since become a professor at Tokyo Zokei University. The first thing I designed after forming this group was an ashtray called "KUL". At that time, many novelists, painters and other people who did good work were always puffing on cigarettes. I thought that if you didn't smoke, you wouldn't come up with good ideas. I was a heavy smoker too. So I decided to design an ashtray for myself first. Ordinary ashtrays have an indented rim to temporarily hold a cigarette, but I wanted to create something like a personalised cigarette stand, so I made a small round ball with an indented rim out of porcelain. I It is portable and can be placed in a hand-held vessel, which then becomes an ashtray. I thought this was an interesting idea. However, I thought some people might not like the idea of using a dish as an ashtray, so I also made a saucer and decided to sell it as a set with the two balls. If there are more people, you can add more balls, and the ceramic absorbs heat, so when the cigarette is shortened and hits the balls, it naturally extinguishes the fire. I think the set of a saucer and two balls cost about 2000 yen and sold well.

ー Nowadays, many young designers are not very good at going out and selling themselves, but did you go out and sell yourself at that time?

Komatsu Of course. I targeted fashionable shops with a good sense of style and went to sell my work there myself. The first shop that handled my work was called "Heart art", which was located near Omotesando Station in Tokyo and was run by fujie textile, a company designed by textile designer Mr. Hiroshi Awatsuji. Both fujie textile and its shop were very popular at the time. There was a unique manager at that shop, who selected and handled the designs he liked, and he also put my ashtrays there, which he often sold. It was about 40 years ago, but back then there was no courier service like there is now, so when I got an order, I had to take the pieces myself and deliver them to the shop by train, not one or two, but 10 or 20, so it was heavy and hard work. But the fact that these popular shops were handling my work helped me gain a good reputation, and I gradually began to receive more and more job offers.

ー You have also created a number of other blockbuster products, which have become your masterpieces. I would like to ask you about the origin of some of your ideas. First, I would like to ask you about the "Crinkle Series", which also became a big hit. The coffee cup and saucer you brewed today is also from the "Crinkle Series". It looks thin and delicate, but it is very smooth and easy to drink from. The wrinkled part of the saucer reflects the light and is beautiful.

"Crinkle Series, coffee cup and saucer"

Ceramic Japan(1983)

Komatsu Unfortunately, this cup has been discontinued, but it is also in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. The idea for the "Crinkle Series" came from plaster, which is an important material for pottery. Besides being used as a material for making moulds, plaster also absorbs moisture and is useful for pressing clay to dry. When you make a plaster mould, you use a lot of plaster, so there is always some left over, but if you leave the left over at random, after a while it hardens and the pattern of the place where you left it will be copied on the bottom in reverse. I think everyone who uses plaster knows that, but in my case I was stirred by the idea that I could do something, that I wanted to try something, and I immediately tried different things. I put the plaster on different materials - cardboard, rubber, cloth - and look at the pattern that is copied. Then I would arrive at paper bags. The most popular piece of work was based on the wrinkles of a paper bag. I first make the paper bag myself to create the wrinkles, but I try to utilise the natural expression of the paper material rather than artificially. I look at the wrinkles, think about them for a while, and finally choose the one I like best and take a mould of it. It's not something that can be done quickly.

ー Everyone knew that patterns could be copied onto plaster, but you decided to turn this into a work of art, which was born from your own unique perspective and ideas. Did you also have in mind what Mr. Lindberg said to you, "You have to create something that no one else has created"?

Komatsu I always want to have that attitude. I am always looking for something interesting, and I am always interested in everything I see, or perhaps I have a strong sense of curiosity. Or maybe I am greedy.

I started out doing everything myself, including the firing of the "Crinkle Series", but now they are made by Ceramic Japan. I am deeply moved by the fact that they are still being sold for a long time. Maybe it's good that it has a strange and unique atmosphere, neither Japanese nor Western tableware.

ー The "Crinkle Series" was developed not only in porcelain, but also in glass materials and other materials, but the production methods were different for each, weren't they?

Komatsu Yes, the production process is completely different from pottery. The glass manufacturer Kimura Glass saw the "Crinkle Series" tumblers and approached us to produce the glass "Crumple Series". In the case of pottery, clay is poured into plaster moulds, but in the case of glass, it is blown into cast metal moulds. Glass does not produce the same fine wrinkle patterns as pottery, and it took a lot of trial and error at first.

ー There were a lot of hardships involved in bringing it to fruition, weren't there? Next, how about the origin of the idea for the "KUU Series " with its many holes?

Komatsu This was born out of the idea of doing the opposite of decoration. Decoration is a process of adding something extra. So I thought I would try to create something by doing the opposite of decoration. I thought it would be interesting to make a shape first, and then make holes in it, and as I made more and more holes, the shape became bigger and bigger, and as I made more and more holes, it became nothing.

ー I wondered, when I asked you, do you usually discover something while creating with your hands, rather than conceptualising in your head or drawing sketches?

Komatsu Sometimes I draw sketches at first, but I usually make things with my hands right from there. I once saw a micrograph (a picture magnified under a microscope) of the nerves in the brain. There are several nerves that are constantly moving in the brain, and it is said that when a person is thinking about various things, some of them are connected at a certain moment, and that is when an idea is born. So I guess that's how inspiration comes to us all of a sudden. In order to get such opportunities, it is probably important to see and hear various things on a regular basis and to gain various experiences on a daily basis.

ー It's interesting. Can you tell us about another of your major works, the door handle "SOYUSHI"? In your book "Komatsu no hon-1943"(ADP, 2012), you wrote that "design is only possible when there are people who use and see it" (extract from p.103), and I think "SOYUSHI" embodies exactly this idea.

Komatsu This was also an interesting job. I believe that a designer is a person who creates half of the value of a thing, and the other half is created by the user, who makes it more attractive. "SOYUSHI" is a door handle that can be changed. I made the handles available in wood, rubber and ceramic materials so that you can choose what you like and change them. The two ends can be detached so that another material can be inserted. For the door handle of our front door, I cut a branch of sansho (Japanese pepper) from our garden. I sold "SOYUSHI" to a shop called OHS (Toyo Shutter) on the basement floor of the AXIS in Roppongi, Tokyo, and they made it into a product. The "SOYUSHI" was so well received that a second version, "SPIN", was created. The handle part is made of aluminium material, which is also available in a variety of colours and shapes so that you can choose the one you like best. The aluminium material was chosen because it is characterised by its colouring by anodising, which produces very vivid colours, and we wanted to make the most of this.

"SPIN", Toyo Shutter OHS Division (1989)

ー I see that even today, only "SOYUSHI" is available for purchase, and you can choose from three types of natural wood: horse chestnut, bird's eye maple and quince. You design everyday objects like ashtrays, coffee cups and door handles - how do you see the difference between art and design?

Komatsu The better a work of art is, the more expensive it is, the more likely it is to be housed in a museum or owned by a wealthy collector, or to be one-of-a-kind, one-of-a-kind pieces. In other words, they may be described as extraordinary, not something that can be found anywhere in everyday life. Design works, on the other hand, can be produced repeatedly, like prints, and mass production lowers costs and allows them to be used by many different people and to enter into people's lives. Our goal as designers is to make everyday life as comfortable as possible, so design works are focused on everydayness. I think that is the main difference.

ー What made you decide to go into craft design rather than industrial design within product?

Komatsu So you can make a finished product with your own hands. Traditional crafts are the same in this respect, but I think traditional crafts have a strong artistic element because they are one-off productions. Crafts are handicrafts with a human hand somewhere in between, and can be produced repeatedly. The attraction is that it allows it to reach a lot of people. I think it is similar to printmaking. In the Edo period, prints were widely available to the general public and were used as wrapping paper when Japanese pottery was exported. I thought it was interesting to hear that prints and pottery were connected.

ー Nowadays, you can get reasonably good products at inexpensive prices from 100-yen shops and interior design shops. In this context, what are your thoughts on the state and future of handmade craft design?

Komatsu Such products are simple in design and form the basis of everyday life tools. However, I think that alone is boring. Just as people have their own individuality, daily life is more enjoyable and richer when there are various forms of expression. One such expression is craft design.

A university class inspired me to organise my photos

ー From here I would like to ask you about the archive. PLAT's design archive research activities originally started when we realised that there were no museums in Japan that held design archives. As our members are writers and editors, we are not able to create museums, but we are able to conduct interviews, so we are interviewing designers to find out what kind of materials they have and hope to be of help when a museum is established in Japan in the future. The first thing I would like to ask you is about your website. It is very clearly organised and wonderful. You include the names of your works, the year they were created, your own chronology, awards received, a list of museums that have donated works, etc. Who created this?

Komatsu Product designer Mr. Shohei Mihara. I saw Mr. Mihara's website and thought it was well made and good, so I asked him to make it for me.

ー Since you have held solo exhibitions and exhibited at museums in Japan and abroad, I assume that you organise the names of works, production years and chronologies for each exhibition or catalogue, so was this data used as the basis for the website?

Komatsu Yes, that's right. Among my solo exhibitions, I was very happy to have the "Makoto Komatsu exhibition : design + humour" at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo in 2008. The museum has hosted exhibitions by Mr. Isamu Noguchi, Mr. Takashi Kono, Mr. Sori Yanagi, Mr. Riki Watanabe and many others, so I still wonder why they approached me. At that time, I produced a hardcover catalogue, which was designed by a student of mine at Musashino Art University, who is good at graphics.

ー Your website also features a number of photographs of your work - are these photographs in data format?

Komatsu I started organising photographs when I started teaching at university. I taught at Musashino Art University as a full-time lecturer and at Aichi University of the Arts as a part-time lecturer, and I needed to use slides when I gave lectures there. In the beginning I used a slide projector to show positive films one by one. At some point, everyone started using computers, and I was surprised when another teacher said to me, "You still use slides?" (laughs). So I converted all the positives into data myself. I keep the photographic data on a USB. I also store images and materials from my final lectures on USBs, which are small and convenient. I still have the positive film as well. Neither the positives nor the photographic data are organised properly, though.

ー The list of national and international museum collections on your website includes MoMA, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the National Museum of Modern Art, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, the UK, China, Korea, Canada and Finland - an impressive number. How did you come to be in the collection?

Komatsu I have never contacted the museum myself; in most cases, the museum contacted me. One of the opportunities came when my work was published in the Italian architectural design magazine "ABITARE". In the section at the end of the magazine that introduces designs from different countries, my work from the "Crinkle Series" was featured. I got a letter from Mr. Stewart Johnson, a curator at MoMA, who saw it and said, "You're doing interesting things, what else are you doing?". I was so happy. I immediately asked Ms. M to write back, and I sent him a photo of the work and the actual piece, and he collected a few other pieces, so maybe it was thanks to Ms. M. The writing in Ms. Ms. M's letter writing was really wonderful, and when I went to Sweden, Mr. Lindberg said to me: "Your letter writing was wonderful. It was a good letter". He asked me, "Do you speak English?" When I said "No", he was very surprised (laughs).

ー Were the photographs of your work published in "ABITARE" large, such as a full page?

Komatsu No, it is a very small photograph. It was a photograph taken by the photographer Mr. Mitsumasa Fujitsuka. When I started my activities, I often asked Mr. Fujitsuka to take photographs of my work. His photographs are very appealing. The photographs of the "Crinkle Series" taken by him were first published in Japan on a full page in "KATEIGAHO", and that ignited a firestorm, or so to say, and they became a big hit with a huge response. I don't remember exactly why it was published, but maybe he told the editorial staff that there was a guy who was making something interesting. From that point on, work started pouring in, and I'm really grateful to him.

ー Photographs of your work in the "Crinkle Series" were published in "Interior JAPAN INTERIOR DESIGN" and received a positive response.

Komatsu "Interior JAPAN INTERIOR DESIGN" often featured my work, especially when they did special articles on tableware. I also applied to be included in the Design Yearbook. I often received letters from museums abroad wanting to collect my work or participate in exhibitions after seeing photographs of my work published in those design yearbooks. Looking back, in many cases, it was the publication in such magazines or yearbook books that led to the museum's collection. In "Komatsu no hon-1943", there are photos taken side by side with articles from magazines and design yearbooks in which my work has appeared. You can also find "AXIS" magazine among them. Then there are times when I exhibit my work in exhibitions or donate my work when I participate in workshop events. I have also donated my work to Musashino Art University and Aichi University of the Arts, where I gave classes.

ー What criteria are used for the museum's collection? Are there any conditions for being included in the collection?

Komatsu I don't think it was anything in particular. But I think it is just because the curator likes it. In the case of foreign museums, they used to send me letters because they didn't have e-mail before, and I would just send them the artworks. For example, the letter from MoMA said, "Congratulations, the works by ****, **** and **** are now in our museum's collection". I keep such letters, of course.

ー What do you think about the lack of design museums in Japan that have the function of storing designers' archive material, compared to the situation in other countries where collections are actively being built?

Komatsu I still simply wish that there was a design museum in Japan. The problem is probably funding, people and management methods. I know there are a lot of people who say different things, but I think it would be better to just create a museum and then think about it. I don't think it's possible to create something big from the start, so I think it's fine to start on a small scale. I think it would be good to put together a scale of 10 works by each designer, with the rest being data, and then just make it, and think about it as you walk around. Otherwise, I don't think it will ever come into being.

ー The book "Komatsu no hon-1943" is a valuable book that tells the story of your life, including your childhood, how you became interested in design, what you did in Sweden, etc., and also includes information such as photos and lists of your works. Some designers don't make books for the rest of their lives, but I think a book is an important archival document that conveys not only photographs of their work, but also their thoughts and ideas to future generations.

Komatsu So there are people like that. I had a strong desire to bequeath this kind of book to future generations, so when I retired, with the support of the university, I self-published it through Ms. Keiko Kubota's ADP. At the end of the book, I wrote what I wanted to tell my children. I hope that by publishing these books, I can be of help to someone or something.

Organisation and storage of models and prototypes in the workshop

Plaster moulds, ceramic colour swatches, toys purchased abroad and many other items in the Komatsu Studio

ー You organise the cardboard boxes in your studio with photos of the items inside on the front. Do you have any staff or apprentices who could take over from you or organise the materials?

Komatsu I put the photos on the cardboard for my own children, so that they could see at a glance what was inside. There were people who helped me in the studio for about five years before, and there were a few people who came for a few months for practical training, but none of them were my apprentices. In the beginning, I was very busy doing everything by myself, from planning and production to delivery and shipping, so there were times when I asked people to help me. When I received a lot of orders, I would work through the night. I was so busy that I was physically exhausted. When I started teaching at university, I realised that I couldn't manage both, so I started asking Ceramic Japan to make my ceramics and other works for me.

The photos are organised on cardboard. Tools for production are hung on the walls

ー There are many models and prototypes in the workshop, but how are other sketches and drawings organised and stored?

Komatsu In my case, I rarely draw drawings, although I sometimes make simple sketches at the beginning. I think about it by immediately making a three-dimensional object, so I probably make more models and prototypes than sketches. I don't even state the year of creation on the models and prototypes, and I don't take photographs of them.

ー Do you keep magazine articles and other materials from when you were interviewed?

Komatsu I keep the ones in which my work has been published, but I don't keep them in any particular order; I just put them in a box.

ー Do you have a desire to bequeath these works, prototypes and documents of yours to future generations so that students and young people can see and learn from them?

Komatsu Of course there is. What makes me happiest is when people empathise with what I design and actually use it in their daily lives.

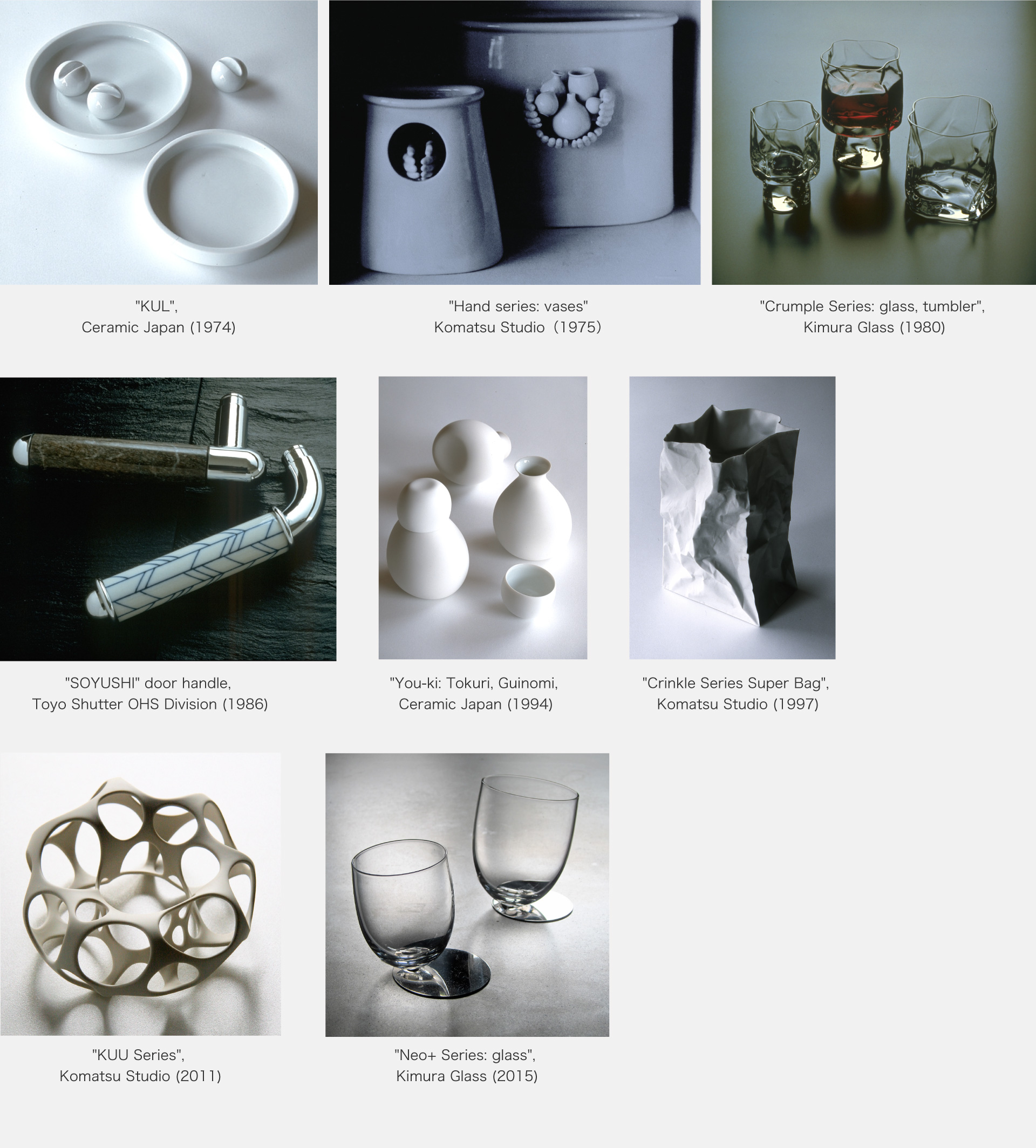

ー In June this year, Ceramic Japan presented new products at Interior Lifestyle Tokyo 2023 held at Tokyo Big Sight. One of them, "MUSUBU", has a very unique shape like intersecting tubes. I was so attracted to it that I picked it up and looked at it.

Komatsu It's shaped like a circle of wisdom. There is a big German trade fair called Messe Frankfurt, and I went there in 2020 with the president of Ceramic Japan to inspect it. Various manufacturers are exhibiting their products, but they are all making the same kind of products and competing with each other. The president and I discussed the idea that Ceramic Japan should not compete in this way, but rather create something that no other manufacturer is doing. So I thought about whether I could make something interesting and came up with that vase. The manufacturing process is very difficult. Normally, people would say it is difficult to make and refuse, but this is one proposal that Ceramic Japan should make something that cannot be made elsewhere.

I am often asked if the tube is made by rounding it, which is possible when the clay is soft, but this is made of two parts, each of which is moulded and then joined together before baking, you can fill either mouth with water and arrange flowers. I didn't glaze them because I wanted to make the intricate forms more visible by not reflecting the light. The world of floral arrangements is very diverse these days. I'm hoping that people will use it in interesting ways, such as turning it upside down and arranging flowers in between.

"MUSUBU" (left) and "YAGI", Ceramic Japan (2023)

ー It would look great on a table in a hotel or restaurant. I understand that "MUSUBU", "YAGI" and "TORI" will be released by Ceramic Japan this autumn. We continue to look forward to that new work and your future works. Thank you very much for your valuable talk today.

Enquiry:

MAKOTO KOMATSU

https://www.makoto-komatsu.com