Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Toshiyuki Kita

Product Designer

Date: 26 June 2018, 15:30 - 17:30,

Location: Toshiyuki Kita Design Institute

Interviewee: Toshiyuki Kita

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota and Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Toshiyuki Kita

Product Designer

1942 Born in Osaka

1962 Graduated from Naniwa Junior College (now Osaka University of Arts Junior College)

Department of Design and Fine Arts, majoring in Industrial Design

1967 Founds IDK Design Institute (now Toshiyuki Kita Design Institute)

1969 Begins design activities based in Italy and Japan

2010- Professor at Osaka University of Arts

Description

Description

Almost 40 years ago, in 1980, the launch of the “WINK” chair was big news in the Japanese design world. The reason for this is the Cassina, a prestigious Italian furniture company, commissioned a Japanese designer who was unknown at the time, to design this unique chair. It attracted attention at the Salone del Mobile in Milan, and the following year it became a huge success in the US market and was included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Toshiyuki Kita, an unknown designer, was instantly recognised as a world-famous designer.

At the same time, people in Japan were beginning to pay more attention to the “culture of life”, as they had enough food and clothing. The designs of Ettore Sottsass and others were taking the world by storm, with many cafés, restaurants and products of innovative design appearing in the Japanese cities. This was the first year of design in Japan. Kita was based in Osaka and Milan, where he expanded his activities and deepened his design.

Kita's works has two approaches: designing for foreign manufacturers, mainly in Italy, and collaborating with Japanese local industries and traditional crafts. The common denominator is that the market is global and the designs are, in a sense, “international cuisine using Japanese ingredients”. For example, the “WINK” chair is said to be “a chair that allows you to sit or lie down freely on a Japanese tatami mat”. The “AQUOS LC-20CI”, which helped to establish LCD TVs in Japan, uses curved lines to create an organic design that is less high-tech. For the next ten years, Kita’s LCD televisions became the idols of the tea room. Today, based in Japan and Milan, Kita continues to travel the world, experiencing international design, talking to people and working on several projects at the same time to create his own unique designs.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

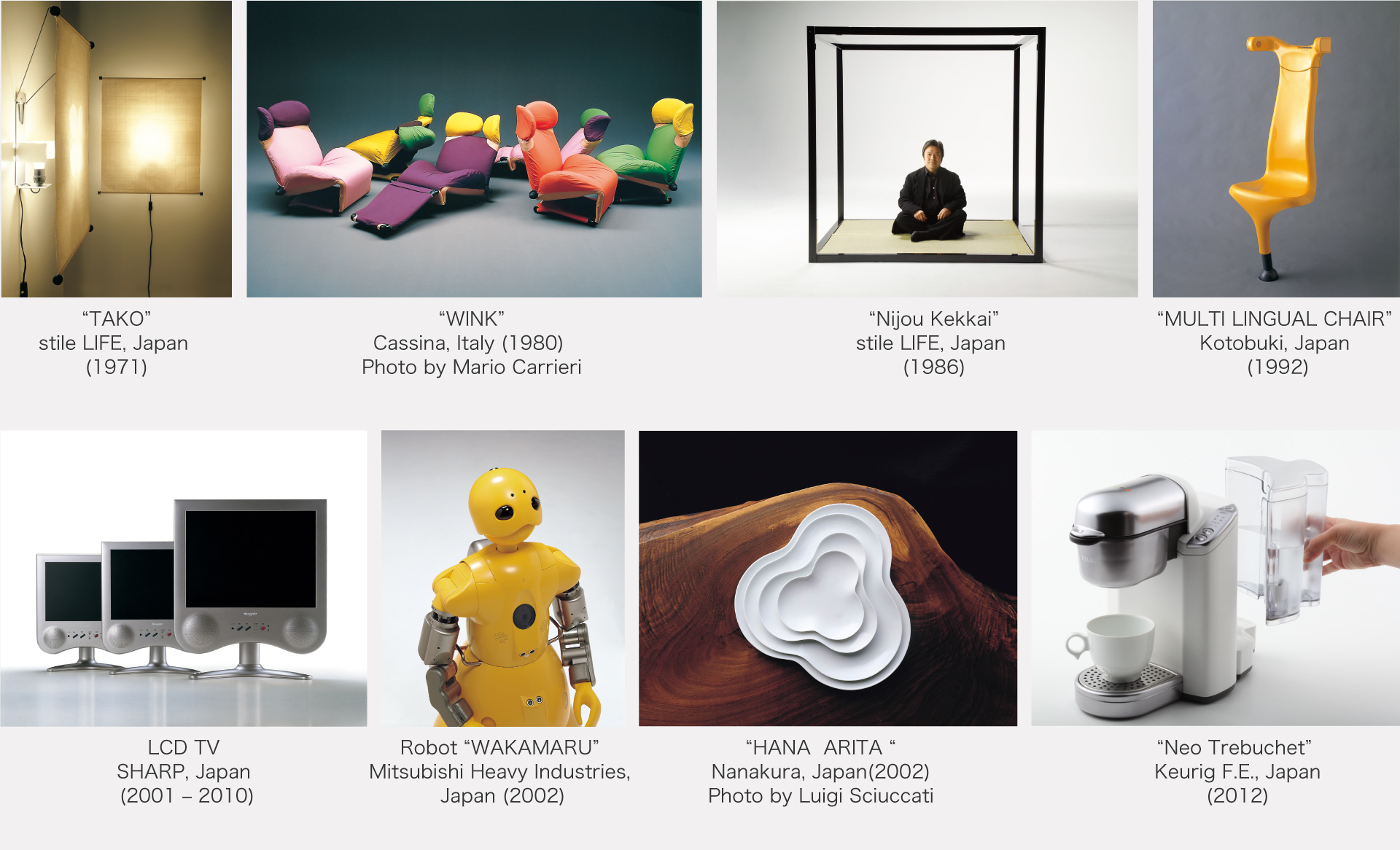

“SARUYAMA” Moroso, Italy (1967), “KYO” still LIFE, Japan (1971), “TAKO” still LIFE, Japan (1971), “WINK” Cassina, Italy (1980), “KICK” Cassina, Italy (1983), “Nijou Kekkai” style LIFE, Japan (1986), “WAJIMA” Omukai Kosaido, Japan (1986), “REPRO” INTERFORM, Japan (1988), “MIRAI” CASAS, Spain (1989), “RONDINE” MAGIS, Italy (1991), "TWO POINTS WATCH" MIZ, Japan (1991), “MULTI LINGUAL CHAIR” Kotobuki, Japan, for the Japanese pavilion at the Seville World's Fair 1992. “AKI.BIKI.CANTA” Cassina, Italy (1996), “DODO” Cassina, Italy (1998), LCD TV SHARP, Japan (2001 – 2010), “Robot WAKAMARU” Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Japan (2002), “ORI” Bonardo, Italy (2004), “Neo Trebier” Keurig F.E., Japan (2012)

Main publications

“Toshiyuki Kita’s Design”, Rikuyosha (1990), “Toshiyuki Kita The Soul of Design”, Rikuyosha (1990), “Paper and Lacquer: Tradition and Revival”, Rikuyosha (1999),”The Power of Design to Create Hit Products”, Nihon Keizai Shimbun Publishing(2007). “Local Industry + Design” Gakugei Shuppansha (2009), “Toshiyuki Kita Design no Tanken” Gakugei Shuppansha (2012), etc.

Major Awards

1981 The 9th Kunii Kitaro Industrial Craft Award (Japan) 1983 Product Design Award, IBD Prize (USA) 1985 Mainichi Design Award (Japan) 1990 Gold Prize, Delta de Oro, Spain 2011 Compasso d'Oro International Award of Merit (Italy) 2017 Order of Merit Commendatore (Italy) 2018 Intellectual Property Merit Award, Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and Japan Patent Office (Japan)

Interview

Interview

Japan has “no seat at the table” unless it makes the best products in the world

Based in Japan and Italy

― Mr.Kita has been one of the pioneers of international design since the “WINK” chair was launched at the prestigious Italian furniture manufacturer Cassina. How did you end up in Milan in the first place?

Kita Ever since I was a child, I had a premonition that I would go to Italy in the future. The direct impetus came from a design trip to Europe in 1967, when I had the opportunity to visit a trade fair in Milan. About 2000 furniture, kitchen and lighting companies were presenting their new products and I was overwhelmed by the otherworldliness of it all. I wanted to know more about Italy and Europe, so the following year I went to Milan with a small Italian pocket dictionary that I had bought in junior high school, planning to spend it in three months to see as much as I could with the money I had to live in Milan for a year or so. Then I worked at a design agency, my friend had introduced me in Milan for about 8 months. After that, I started working on original designs for the furniture company Bernini.

― What kind of design work did you do??

Kita At Bernini, I designed a pipe chair, and shortly before I left for Italy, I had a chance to meet a Japanese washi paper craftsman, and I tried to revive a traditional Japanese craft that was in decline. The light “TAKO” made of washi paper, was introduced in 1972 by the Milanese lighting manufacturer , and the sofa “SARUYAMA” (Photo 1), introduced in 1967 by Moroso, was inspired by the Japanese lifestyle of living freely on tatami mats. As the name suggests, “SARUYAMA” is a sofa with a free and playful spirit, and has recently been used in the entire headquarters building of the Venice Biennale and in the New York airport.

Photo 1: “SARUYAMA” Photo by Tom Vack

― And finally, in 1980, you introduced the chair “WINK”.

Kita I was commissioned by Cassina in 1976. They had already produced Bernini products and “TAKO”, so they asked me to come up with a chair that was very Japanese. In our childhood, the only place where you could find a chair and a table was at school, and most families lived on tatami mats. We wanted to design a chair that was flexible and could change shape depending on your posture, so we worked on the idea for about two years. In 1980, “WINK” made its debut at the Salone del Mobile in Milan as a new concept chair that made full use of technology, and was followed by “KICK” (Photo 2), a side table to match “WINK”.

Photo 2: KICK

Local industry survives by design

― Since the success of “WINK”, you have been involved in a variety of product design projects, from furniture to LCD TVs and robots. What is it that you are focusing on these days?

Kita Working with local industries, which I have been doing for many years. Design can’t move forward unless it is consumed, can it? Design needs constant innovation as science and technology and needs change. The design of televisions has changed from cathode ray tubes to liquid crystal and organic light emitting diodes. The car will look different when the fuel goes from petrol to electricity. The same is true for local industry. It is good when the technology is good and valuable, but when a better technology comes out, it will be replaced by a new one. That’s why it‘s important for the designers involved to always be a little ahead of the times and be aware of the balance between people’s lives, technology and craftsmanship.

― How do you see the local industry in Japan today?

Kita From the post-war period to the high-growth period, the Japanese economy has been successful, especially in the export industry, due to the diligence of its workers and the adoption of the best aspects of the West. Today, however, China and other Asian countries are transforming themselves further by adopting design as their markets develop. In this context, Japanese local industry needs to be very conscious of the world.

― Do you also work with local industries in China?

Kita Recently, I was involved in a project to restore Song dynasty pottery that was unearthed in China. In January this year, the Salone del Mobile in Milan, we presented the “SONG” series. We have developed about 40 different products based on four themes that were once part of Chinese culture: flowers, tea, gastronomy and wine. In terms of design, the theme is to connect China's unique pottery culture to the future market, and for this reason the glazes are mineral-based and ecological, as they were in the “Song Dynasty”. In recent years, the revival of traditional crafts such as lacquer and pottery, as well as local industries, has begun in many parts of China.

― So a local project in China is suddenly making its way to the global market in Milan?

Kita Most Chinese companies today have presidents in their 30s and 40s, and the projects progress very quickly. When we send them a 3D drawing, they immediately make a 3D copy of the mock-up. When we go to the site, everyone from the CEO to the shop-floor staff gathers around the mock-up and discusses and solves problems in order to commercialise the product. The rise of AI and IoT is further accelerating the commercialisation process.

― What do you think of Japanese local industries?

Kita In a recent project I was involved in in Japan, the goal was to combine the domestic materials, cedar and bamboo with excellent craftsmanship. In Japan, 70% of the land is forested, but the self-sufficiency rate of timber is only about 30%, so many natural resources are not being used to their full potential. We wanted to open up new possibilities for wood products through design, so we spent about three years working on this project.

One is the project of cedar from Akita Prefecture. The Akita cedar grows slowly in cold climates, so its annual rings are tightly packed and the wood is light and beautifully grained. With the help of some of the best craftsmen and woodworkers in the prefecture, we developed about 10 products, including chairs and tables, which were presented at the Salone del Mobile in Milan as the “Akita Collection”. Although we use different processing techniques, we use the same materials so there is a sense of unity. The uncompromising attention to detail and the use of local nature were highly appreciated.

The other material is bamboo from Shimane Prefecture. A new material has been developed by a technique that processes bamboo into flat sheets, leaving the knots and fibers of the surface skin intact. Bamboo is edible when it is in the ground, and once it is above ground, it becomes a mature tree in three or four years and can last up to 100 years. Not only that, but bamboo forests exist all over Japan and grow very fast, making it an ideal sustainable material. Now that we have developed the technology to produce flat sheets of bamboo 70 to 100 millimetres wide and up to 2 metres long, we have designed and developed chairs, tables and other items using the flat sheets and launched them under the brand “Flat Bamboo Shimane”. The “Akita Collection” and the “Flat Bamboo Simane” (Photo 3) will be launched globally after the the Salone del Mobile in Milan.

Photo 3: Flat Bamboo Shimane

― There are many different issues when it comes to local industry.

Kita There are many themes in our work with local industry, but one of our aims in working with local industry is to revive lifestyle culture. This will energise the market and ultimately lead to the development of the industrial economy. In our recently announced “Hotel Space Design Project” in Asahikawa, Hokkaido, we have developed products based on the theme of high-quality hotel interiors. When it comes to hotel furniture, one can’t help but think of the West, but this time we dared to focus on the theme of rich local materials, Japanese lifestyle and indigenous Hokkaido culture. Members of the local furniture industry association made prototypes of the furniture and presented them at the Asahikawa Design Week in June. It was also unveiled in Tokyo in the summer.

Design is born from lifestyle culture

― You mentioned earlier about “revive lifestyle culture”, could you tell us more about this?

Kita Over the last 60 years or so, Italian design has been driven by the need to enhance the living environment and communication between people. Italian rich design culture is the result of an insatiable demand for comfort and practicality in living and working environments, and the practice of comfortable living. My design origins lie in the fact that I happened to live in Italy during a period of change since the end of the sixties.

― In Japan, design is often seen as an economic activity, a tool to promote industry. It’s not about enriching people’s lives, it’s about selling.

Kita As I mentioned earlier, design in Asia is developing at a very fast pace. A few years ago, I worked as a design advisor for the Chinese government for about three years, and I witnessed how the improvement of people’s lives and the development of design contributed greatly to the development of lifestyle culture and industrial economy. In Shanghai and Guangzhou, for example, there are trade fairs twice the size of the Salone del Mobile in Milan. I recently visited a trade fair for consumer electronics in Shanghai and was amazed at the development. The living environment of the urban middle class has become so rich that AI is being used in the kitchen... in ovens, ranges and refrigerators, for example. We’re also seeing a lot of adoption of IoT, such as being connected to your phone to manage food recipes and storage. The other day I was in the home appliances section of Harrods department store in the UK and there were lots of large Chinese and Korean fridges on display.

― What is the background to the rapid growth of Chinese products?

Kita Since around 2007, China has been implementing design policies at a furious pace, aiming to become a "design nation". One of them is the housing policy. The average size of a newly built house is about 130 square meters, and it is furnished with the most advanced home appliances and furniture, and 4K TVs have already started to be used in households. This momentum is not limited to housing, but is spreading to cities as a whole, and infrastructure development such as highways and bullet trains across China is also expanding at an accelerating pace.

― So how can we work to improve the living environment in Japan?

Kita I am concerned that the average Japanese person’s lifestyle has not changed significantly compared to other Asian countries. If the quality of our daily lives and the spaces in which we live doesn’t improve, I don’t think design and manufacturing will develop either. I think the challenge for the future is how to change and thicken this part of the world. In the post-war period, Japanese housing policy was so severely damaged by the war that much of the time was spent on infrastructure development and the enrichment of lifestyle and culture was put on the back burner. More than 70 years after the war, the emphasis is still on supply rather than quality, and the general picture of a “nice life” is still not clear. On the other hand, with a declining birth rate, a declining population and an ageing society, we believe that it is very important to make the best use of the buildings that already exist and that have been designed to withstand earthquakes. From this point of view, in 2012, we proposed a renovation project for housing complexes called “Renovetta”, and we are now working hard with many people to make it a reality.

― What do you think the future of manufacturing in Japan should aim for?

Kita Japan is a country that says “there is no seat for you” unless we combine originality and high technology with innovation, especially in small and medium-sized companies, and make the best products in the world. In order to achieve this, we must first create places where people can live comfortably, even if they are a little cramped. I believe that the enrichment of the living environment is the key to the growth of design in Japan.

― It’s a pity that Japanese government doesn’t have the same design policy as China.

Kita The Japanese government also acknowledges the importance of design: the “Design Management” declaration was announced in May 2018, based on the “Study Group on Industrial Competitiveness and Design” organized by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Japan Patent Office since 2017. The main objective of the study group was to identify design policy issues and research ways to address them in order to strengthen the international competitiveness of Japanese companies.

Our approach to the archive

― Now, we would like to ask you about your own design archive, as you have a sense of crisis about Japanese design.

Kita A few years ago, I finally started to organize my works and documents, but I’m always away from the office, so I haven’t made much progress. Specifically, for each project, I have not only the output but also the data and photographs, from the planning to the design drawings, on CD. We also keep a large number of domestic and international articles, lecture records, and catalogues of the products we have designed, by year and theme. We also keep catalogues of the products we have designed. For the moment, we have a separate warehouse for all of our three-dimensional objects, but not all of them.

― Looking at your magazine article files, there are a lot of articles from overseas.

Kita There are more articles from foreign media, mainly from Italy, but also from France, Germany and China, than from Japan. There are many people who drop by because they are in Osaka. I think of this office as a design salon in Osaka, it can hold about 50 people, so when we have clients from home and abroad, we have small lectures and parties. Local designers and managers also come here, so there is a certain intimacy that you don’t find anywhere else.

― You have held solo exhibitions all over the world, at the Centre Pompidou, at the Living Design Centre OZONE in Shinjuku, and in churches in Milan and Piedmont (Photo 4). What do you do with them? Graphic designers donate some posters directly to the local museum after an exhibition

Photo 4: The church in Piedmont where the exhibition was held

Kita Many of our works are three-dimensional, so we don't often donate them directly. Most of them are made with the help of manufacturers or are stored in my own warehouse. In my case, however, I am fortunate that many of my works are in museums around the world, including MoMA, the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg (MK&G) and The Centre Pompidou in Paris.

― Why do you receive so many requests from abroad?

Kita Perhaps the main reason is that our work has been featured in the international media and sold on the global market. Foreign journalists tell us that “Kita’s designs incorporate Japanese culture as well as Italian and other foreign technology and culture”. In the globalised world of manufacturing, design is something that is used in everyday life, so it‘s nice to be seen in this light.

― Thank you very much for your time.

Enquiry:

Toshiyuki Kita Design Institute

http://www.toshiyukikita.com/jp/