Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

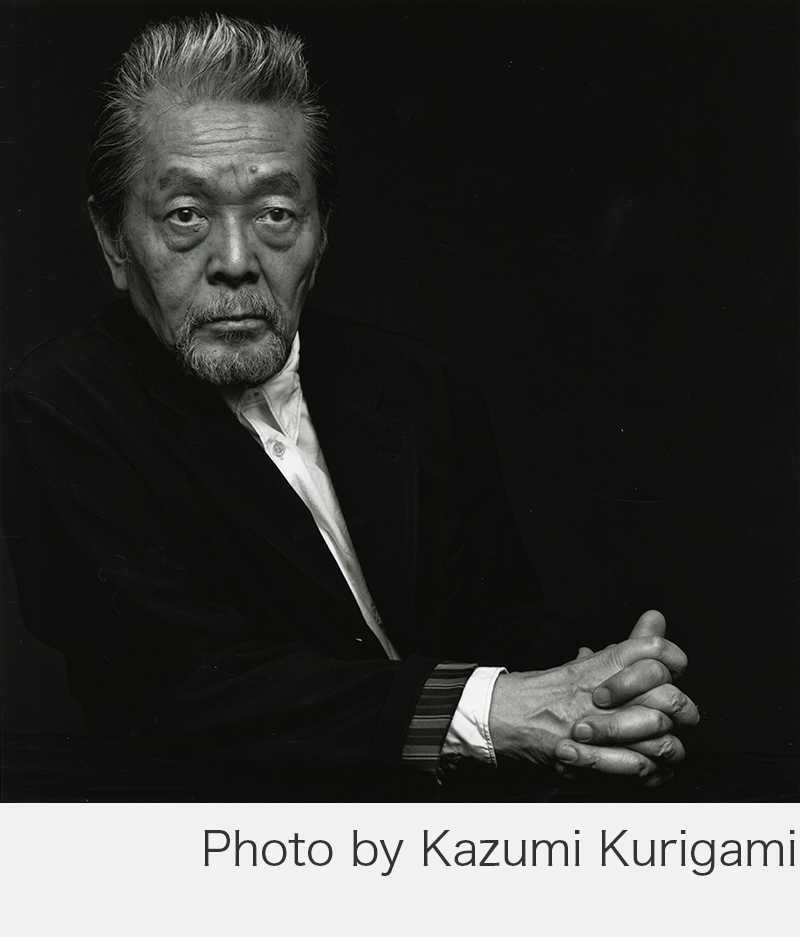

Akira Uno

Illustrator, Graphic designer

Interview: 15 December 2022, 15:00-16:30

Location: DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion

Interviewee: Akira Uno, Mieko Uno

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

PROFILE

Profile

Akira Uno

Illustrator, Graphic designer

1934 Born in Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture.

1952 Graduated from Nagoya City Municipal Seiryo High School, Department of Design (now Nagoya City Industrial Arts High School).

1956 Joined the advertising department of Calpis Co., Ltd.

Awarded a special prize at the 6th JAAC Exhibition for the poster "Ballet Carmen" (poster).

1957 Became a freelance designer.

1960 Joined Nippon Design Center.

Awarded Member Prize at the 10th JAAC Exhibition for Asahi Kasei Kashimikuron (poster).

1964 Founded Studio Ilfil with Tadanori Yokoo and Tsunao Harada (left the following year); founded Tokyo Illustrators Club with Tadahito Takimoto, Makoto Wada, Tadanori Yokoo and others.

1965 Founded Studio Re (dissolved in 1968, became freelance), participated in the graphic design exhibition “Persona”.

1966 Tokyo Illustrators' Club Award, "Anoko" (Riron-sha), "Kindai Kenchiku" (Kindai Kenchiku-sha, 1965-66) (cover).

1982 13th Kodansha Publishing Culture Award, illustration prize, "The Fan in Paris" (by Kimiko Koizumi), "Gastronomist" (by Tomoko Aoyagi).

1989 15th Sanrio Art Award.

1992 6th Akai Tori Illustration Award (“Seagull's House”, by Akio Yamashita, Riron-sha).

1999 Medal with Purple Ribbon.

2008 13th Japan Picture Book Award (The Devil's Apple, written by Katsuhiko Funazaki).

2010 The Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette.

"Akira Uno Ehibition AQUIRAX", Kariya City Art Museum, Aichi.

2015 Awarded the 22nd Yomiuri Theatre Grand Prize Selection Committee's Special Prize (art for Shinjuku Ryozanbaku's “Jaguar's Eye”, puppet art for Yukiza's “Old Refrain”).

Currently member of TIS (Tokyo Illustrators Society)

Description

Description

For more than 60 years since the late 1950s, Akira Uno (Aquirax) has been a rare genius whose illustrations and designs continue to attract people. A pioneer in the field of illustration, writers, musicians and stage directors are still fascinated by his unimaginable expressions. Poet Kazuko Shiraishi describes him as follows. “Akira Uno's world is at once far and near, near and far. This is where Akira Uno's popularity and mystery lie. Across Japan, Akira Uno and his paintings have laid thousands, millions and millions of eggs. Eggs are fans. They are the intoxicated people who have fallen in love with Akira Uno and his paintings. Designer, illustrator, painter, whatever name you want to give him, he is, in the classical sense, a craftsman of painting and decoration, and there is no one better" (Art Top, No. 31, Geijutsu Shinbunsha, 1975) .

Born in Nagoya in 1934. From the time he was in primary school, his father, a room decorator, taught him how to paint, and he painted even when he was evacuated to a group evacuation site. After the war, when he was a junior high school student, he attended a painting institute where he studied under Haru Miyawaki and aspired to become a painter. In 1949, he entered the design department of Nagoya Municipal Seiryo High School (now Nagoya City Industrial Arts High School), where he honed his skills in design competitions during his studies, which led him to become a designer. After graduation, he worked for Calpis Co., Ltd., and Nippon Design Centre before setting up his own business. He is described as a 'golden left arm' for his overwhelming drawing ability. He continued to be at the forefront as an illustrator and graphic designer, especially in the 1960s and 1970s, when he became associated with subcultures centred on underground theatre companies such as Shuji Terayama's theatrical troupe “Tenjo Sajiki”, which took the world by storm. Posters were removed from the streets, and the enthusiasm of the movement is conveyed in Kazuko Shiraishi's writings. In addition to advertising, illustrations, bookbinding, stage and film posters, he has also worked as a curator, stage designer and artistic director. In recent years, many of Uno's works and materials have been acquired and managed by the Kariya City Art Museum in Aichi Prefecture.

Due to the variety of his work, solo exhibitions are often organised. This is possible because the archive is substantial and well-functioning.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

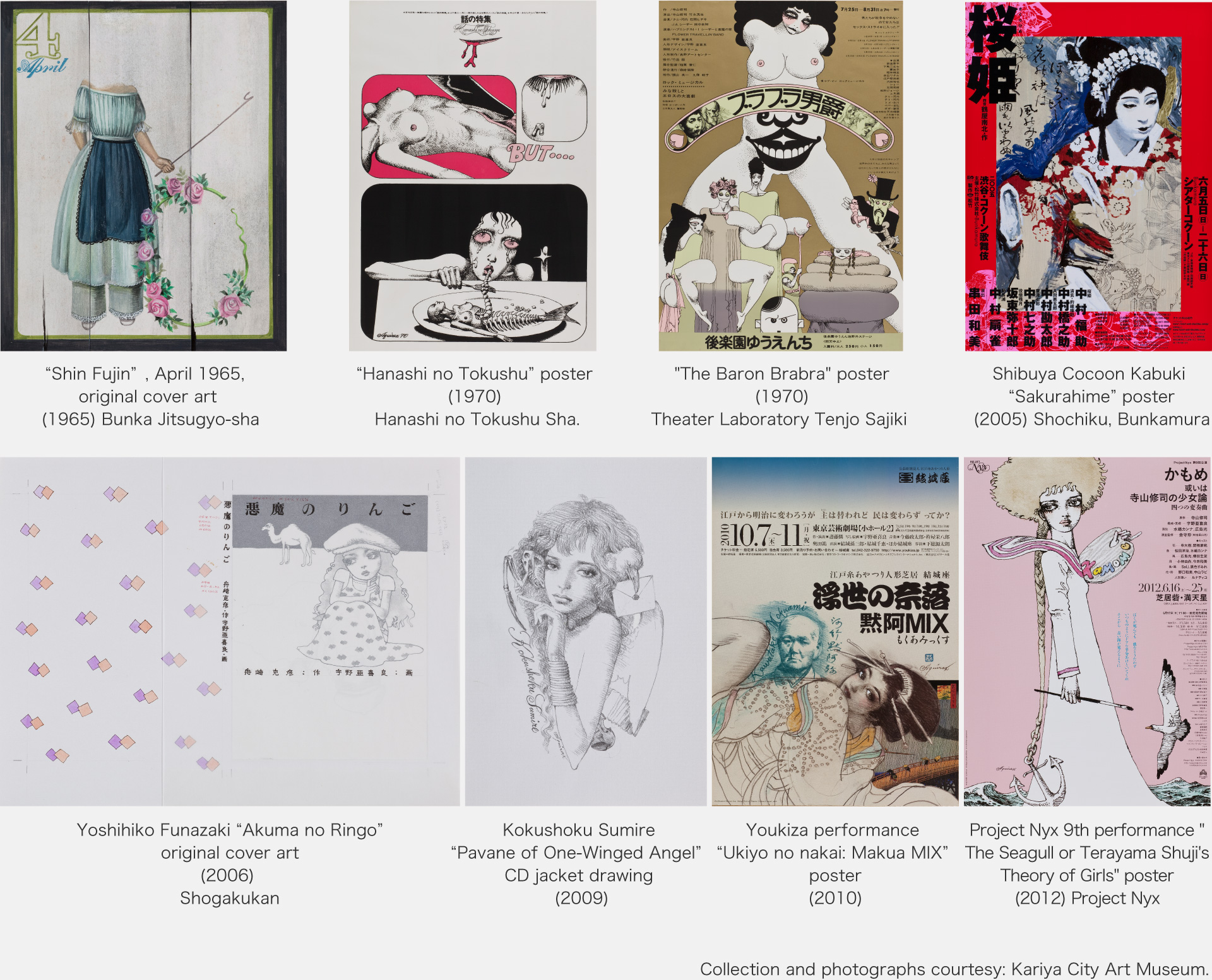

Magazines and Books

Cover design and illustrations for Kappa Books (Kobunsha); logo and cover design for Kappa Homes (Kobunsha); original cover art for Kindai Kenchiku (Kindai Kenchiku-sha, 1965-1966); “Hanashi no Tokushu” (Nihon Company, 1966- ); original cover art and design for Eureka (Seidosha). Illustrations for Yusuke Kaji “The Little Girl of the Sea” (with Tadanori Yokoo, Asahi Press, 1962); illustrations for Yoshitomo Imae “Ano Ko” (Theory-sha, 1966); illustrations for For Ladies Series, including Shuji Terayama “Hitoribocchi no Anata ni” (For you, alone), (Shinshokan, 1965); illustrations for Akio Yamashita “The House of Seagulls” (Rironsha, 1991); illustrations for Tadashi Ozawa “Boku wa Heitaro” (Fukuinkan Shoten, 1994, 2002, 2003); illustrations for Yoshihiko Funazaki “Akuma no Ringo” (Shogakukan, 2006).

Theatre, Film, Music, Events

Stage design for Mokubaza (1962); posters for "The Star Prince” and "The Baron Brabra" (Theater Laboratory Tenjo Sajiki, 1968, 1970); art for Kazuyoshi Kushida's film "Shanghai Bangs King" (On Theater Jiyu Gekijo, 1988); album jacket design for Tomoyasu Hotei “GUITARHYTHM” (Toshiba EMI, 1988); poster design for Azabu Juban Summer Night Festival (1999-); poster for Shibuya Cocoon Kabuki "Sakura Hime" (Shochiku, Bunkamura, 2005, 2009); album jacket design for Sheena Ringo "Ukina" and "Mitsugetsu Sho" (EMI Records Japan, 2013); art for Shinjuku Ryozanbaku “The Eye of the Jaguar” (2015); puppet art for Youkiza “Old Refrain” (2015).

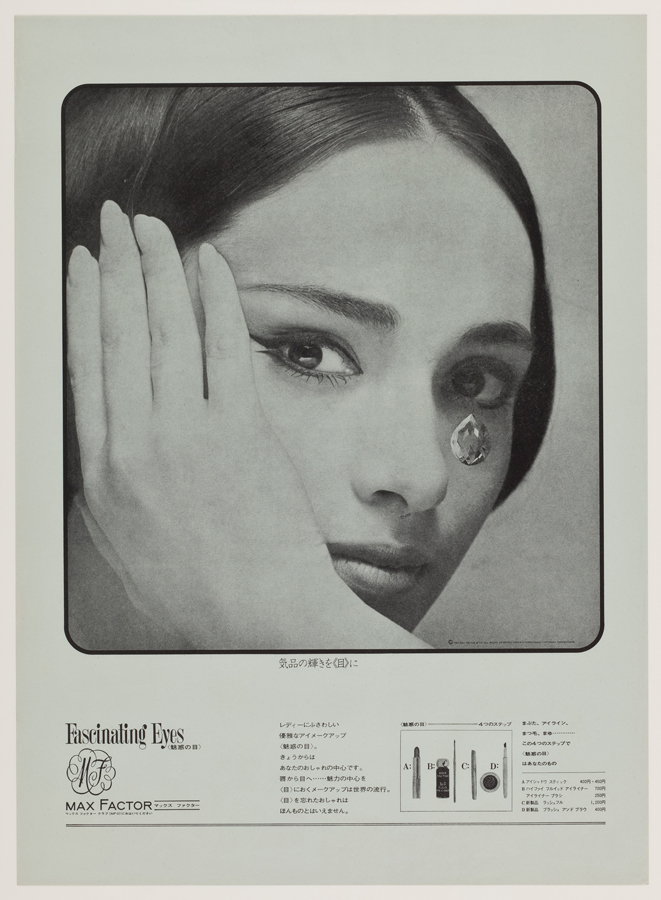

Logos, Packaging, Advertising

Posters for “Max Factor” newspaper ads (Max Factor, 1965-68); logo and packaging for “Meiji Rondo Chocolate” (Meiji, 1966); logo for Shinjuku 'TAKANO” (Shinjuku Takano, 1966-67); commercial, posters for “Sailor 21 gold pen” (Sailor Pen, 1968).

Publications

“Memories of Roses: Akira Uno's Complete Essays 1968-2000” (Tokyo Shoseki, 2000); “Akira Uno 60s Poster Collection” (Bruce Interactions, 2003); “Shiro Neko Tei: A Restaurant with Many Memories” (Shogakukan, 2004); “MONOAQUIRAX + Akira Uno monochrome works" (Aiikusha, 2009); "Akira Uno Chronicle" (Graphics, 2014); "Akira Uno's World of Fantasy Illustrations" (PIE International, 2016).

Animation works

“White Festival” (1964); ”You and Me” (1965); “Noon (Don)” (1966).

Interview

Interview

I want to create a visual scandal that takes the audience by surprise.

Kariya City Art Museum manages the archive

ー We have just seen the ginza graphic gallery's 392nd special exhibition, "Kaleidoscope by Akira Uno" (9 Dec - 31 Jan 2022). You have been active at the forefront as an illustrator and graphic designer for more than half a century since the 1950s. Today I am interviewing Mr Akira Uno in the presence of his wife, Mrs Mieko, and I hope to get a little closer to the source of his creativity, which has transcended the times.

First of all, the exhibition featured works from the collection of the Kariya City Art Museum. We understand that many of Uno's works are in the museum's collection.

Exhibition space on the ground floor of ginza graphic gallery's “Akira Uno Kaleidoscope”. Based on Uno's series of works on the theme of haiku and girls, Junko Tsuda took on the challenge of creating a new expression through special printing design.

Photo by Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

Mieko Uno is from Nagoya City, so we had no contact other than a connection with Aichi Prefecture, but the Kariya City Art Museum approached us.

Akira It seems that it started with a collection from Aichi Prefecture. Kariya City had a large collection of works by painters such as my teacher Haru Miyawaki, Kenkichi Sugimoto and Reiji Yokoi.

ー When were you approached by the museum?

Mieko The first visit was probably about 15 years ago. The museum curator spent about three years carefully looking through the collection, which had been stored in the office warehouse. There were all kinds of illustrations, posters, original drawings, books and even three-dimensional objects from picture books and monographs. I was told that there were 3,000 items in total. He selected that collection, and in 2010, the "Akira Uno exhibition AQUIRAX" was held at the Kariya City Art Museum, and he subsequently collected those works.

Until then, we had only stored the posters in tubes and had not sorted or organised them, but they seemed to be in good condition. The curators organised and examined the entire collection, which was enormous. Ikuko Matsumoto, the current acting director of the museum, has always been in charge of Uno. For this exhibition as well, she discussed the matter with the curator of the ginza graphic gallery and immediately responded. The works are properly organised so that when the need arises to lend them out for an exhibition, the Kariya City Art Museum is contacted. We insure them and deliver them in art packaging.

Akira About 50 posters from the 1960s are displayed on the basement floor of this exhibition, but I didn't have to add a single word of explanation, and the Kariya City Art Museum managed everything from captions to everything else very well.

Fifty posters were displayed on the basement floor at " Akira Uno Kaleidoscope“.

Photo by Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

Mieko But almost ten years have passed since then, and I still rent three boot rooms, which have become crammed with artworks and materials. We are planning to hand this over to the Kariya City Art Museum as well. I hope that in the future they will hold an exhibition of Uno's work, including the new materials I will give them. Until then, Uno also says he has to stay alive.

Akira Makoto Wada passed away in 2019, and other close friends have passed away... I wonder if exhibitions are being planned one after the other, with the feeling that Akira Uno will soon be in trouble (laughs). I myself was not very cooperative because I was not aware of such things, but the Kariya City Art Museum did everything from delivery to creating titles and data.

ー The need to preserve artworks as archives is felt, but public and private museums and universities lack the space, manpower and budget to do so. The fact that museums like Uno's not only have collections, but have also made progress in the archiving and management of their works is truly ideal, and in reality, a rare case.

Akira In the past, we have always consulted the Kariya City Art Museum when we have something to do.

Mieko Kawasaki City Museum also had several pieces in its collection, but they were all ruined when they were flooded by typhoon damage in 2019.

Akira In 2022, there was an exhibition at Sakai Alphonse Mucha Museum in called “Small Room of Ennui - Alphonse Mucha and Aquirax Uno”, which showed the similarities between Mucha and Akira Uno.

Mieko A record 30,000 people visited the museum. This is also the case with works on loan from the Kariya City Art Museum.

Akira Kawasaki City Museum had the idea to do this more than ten years ago. In 2011, we held an exhibition entitled “Akira Uno and Art Nouveau Artists”. I don't think I was influenced by Mucha, and I haven't really thought about it, but I guess other people see similarities in the way he depicts the customs of a certain period, and the way he focuses on women. I think it means that when you put them together, you get an interesting phenomenon, but the Kawasaki City Museum was the first to connect Mucha and me. I am heartbroken that such a place with such a connection has suffered a water disaster.

The transformative nature of the poster medium

ー In 2021, you was publishing a new book of paintings inspired by ancient and modern haiku, entitled “Uno Akira Art Collection Kaleidoscope” (Graphic, Inc.). The exhibition on the first floor of the exhibition space is a kaleidoscope of this book. Junko Tsuda, who was involved in the printing of the book, designed the special printing for the exhibition, and the works jumped out from the book and took on a transformed aspect. The posters were done by Idea Oshima, who was in charge of the book design.

Akira The exhibition on the first floor was a variety of printing creativity based on my drawings by Ms Tsuda. She did something that could be converted into something completely different from the original drawing, in terms of how to demonstrate the originality of printing. Originally, it should have been me who should have done this, but someone else had a more detailed taste than I did, so I just took Ms Tsuda's talents. I felt a little bad for Ms Tsuda if I didn't convey this point to her.

ー Some people might have seen it as Mr Uno's world, but I felt there was a synergy between the original artwork and the print creativity. Without collaboration, it's hard to create new work.

Akira Graphic design and illustration are only possible when there is a client and a medium. Printing techniques such as silk-screen printing are a way of reproducing this, so even if you don't use your own hands, you can reproduce your own sensations. On the other hand, I don't trust printing itself, or rather, I don't have much faith in its reproducibility and recoverability. For example, I look at movie posters posted around town, thinking that the red colour has been removed and the blue colour is probably not the intended colour. To begin with, posters are transformative. As they are put up, they tear and fade. I'm proud to be in that kind of media world, so I'm basically different from a painter. I find that transformation interesting, and it would be interesting if I could specify to the point that I would use red ink that is about two years old. Everyone compliments me on this exhibition, but when they say things like 'the colours are beautiful', I feel like it's not my domain to be praised.

ー Mr Uno was also a leading graphic designer of your time, designing the logotypes for Meiji “Rondo Chocolate” and Shinjuku “TAKANO”, as well as the advertising design for Max Factor. However, you have since deliberately called yourself an 'illustrator'. You say that stage design and art are also included in your work as an illustrator, but can you tell us about the background and your thoughts behind your choice from design to illustration?

Akira In theory, I haven't changed, or I'm happy to be called a graphic designer. It doesn't matter either way. I would even like to have two titles, illustrator and graphic designer, side by side.

As I said earlier, illustration is an art of reproduction, which is different from that of a painter, because it often passes through mechanisms of restoration, such as print media. The interest lies in how it is reproduced.

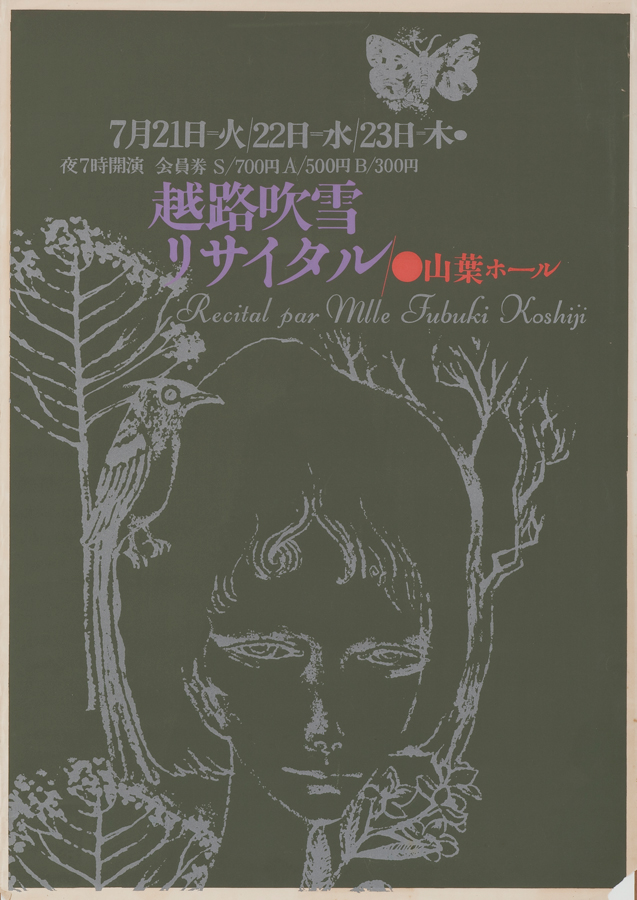

Poster for “Fubuki Koshiji Recital” (1959), AD by Kohei Sugiura. Collection and photograph courtesy: Kariya City Art Museum.

ー You ware actually illustrating and designing at the same time, so it is accurate to mention them together.

Akira I have about six cardboard boxes of publications at work that I drew and designed myself. There was a publisher who wanted to make a complete collection of them, so I was putting them together, but the project was abandoned in 2014 with the publication of “Akira Uno Chronical” (Graphic), so the materials are still packed in boxes and left there.

Now we have a division of labour, or rather, the graphic designer does the binding if there is no visual pictorial element, and if the graphic designer needs a picture, the designer appoints a painter. It is as if the bookbinding designer is ahead of us illustrators. But in our time, Makoto Wada and Tadanori Yokoo had to design their own books too. That was the era. It's a very recent phenomenon. The binding designer chooses the illustrator. When I went to an award party for a female author, there were no illustrators other than myself, and I saw the designer communicating closely with the author. The designers are taking commissions from the authors. The designer is also responsible for socialising, getting on well with the artist, and not many illustrators seem to make that kind of effort.

Uno Akira brought out by Makoto Wada

ー Kappa Books by Kobunsha was a hit label that produced series such as Kappa Novels and Kappa Homes, for which Ikko Tanaka was responsible for the cover design in the 1960s and 1970s.

Akira I did the logo, and in some cases I also drew the illustrations, and in other cases I chose the illustrator.

The relationship between authors and illustrators reminds me of the 'illustration incident' in Kaizan Nakazato's “Daibosatsu Touge” (The Great Bodhisattva Pass). Tsuruzo Ishii drew the illustrations. When the book “Tsuruzo Ishii Zenshu vol.1” (The Complete Works of Tsuruzo Ishii, Vol.1) (Koutaisha, 1934) containing the illustrations was published, the writer Kaizan Nakazato complained that the illustrations were not the work of the artist, but a reproduction of the text, the copyright to which belonged to the author of the text.

He filed a lawsuit against the artist and the publisher, claiming that "without my work, this picture would not exist." I know that the novel is behind the creation of the illustrations, but it is difficult to know how to view creative rights. The court case became a hot topic and public interest in illustrations grew: after a 10-year trial, Tsuruzo won the case, leading to the recognition of the creativity of illustrations.

ー By the way, when and how did your illustration touch change?

Akira I don't really know, myself. In the 1960s, there was a magazine called “Hanashi no Tokushu”. The cover was by Tadanori Yokoo, the art director was Makoto Wada and the editor-in-chief was Yasuhisa Yazaki. They were all close friends. Inside there was a French sensual novel by Isamu Kurita, which Mr Wada had me illustrate. There was also a novel by Shuji Terayama that cynically depicted the times, which he had me illustrate. In one magazine, he let me illustrate everything from pretentious sensual novels to Shuji Terayama's genre comedies. One time, I don't know how it happened, but they gave me a colour page with a female nude spread. I worked with a photographer named Hiroki Hayashi, who was a close friend of mine, and I did body paintings on the woman's body. It was erotic because she was naked, but there were birds there and so on, so it was a nude photo with my painting added. I used a top make-up artist called Goro Ito, which was unthinkable in the publishing world at the time, and for the background artist I added someone who worked on Toho films. A man called Makoto Wada used different genres in my mind at the same time. I don't know what the costs were, but he must have calculated the costs and the effect on book sales, and I think he is an amazing person. In other words, there are several styles in my mind within one period. I would like to think that there is Akira Uno, who comes out when a certain theme, such as a novel, comes along. There are several, depending on how you draw them out.

Working with Shuji Terayama

ー This is an interesting story. As well as Mr Wada's talent, I feel that at the same time there was a demand for your illustrations here and there throughout the period.

Akira At that time, I illustrated girls for Mr Terayama in the For Ladies series, which was a series of lyrical novels, such as “Hitoribocchi no Anata ni” (For you, alone) (Shinshokan, 1965). This was the first time I illustrated a girl. Two years later, in 1967, he set up an underground theatre called Tenjo Sajiki, of which he included Yokoo as a founding member, but I, who had such a good commercial record, was not included. They wouldn't include me. But I can understand that. If he included Akira Uno, they might associate him with girlishness and lyricism, and people might think he had started doing something like Takarazuka. When he wanted to do avant-garde, Shuji Terayama used Tadanori Yokoo, and from about the third film he used me for art, and I went into theatre, but Mr Terayama must have known the kind of Akira Uno was doing.

ー What was the source of the image of the girl at that time?

Akira Nostalgically, the customs of the times, or rather, it came out in me. I think I was influenced by the 'Miyukizoku' - in the summer of 1964, the young people who gathered around Miyuki-dori Avenue in Ginza dominated the scene and were called the 'Miyukizoku'. But they disappeared in autumn due to the crackdown on public morals for the Tokyo Olympics. They lasted only a few months. The men wore an Ivy look, while the women wore white blouses and flats and carried zuda bags. They are a bit semi-long and a bit frilly. Lyrical but avant-garde. It was a Japanese original, completely different from the A-lines that had come from Europe up until then. I think that was a great culture. I was drawing at that time, so I was influenced by it.

Now I draw with the sense that I want to draw a girl who is not from a specific period, with a kind of ambiguous girl psychology. She's an abstract woman.

And at that time I painted matches in gay bars, and I admired the keenness of the gay people's senses. It may also be that I liked Jean Cocteau.

ー Mr Terayama must have also resonated with such danger-filled illustrations.

Akira I met Junichi Nakahara's son and heard that Mr Terayama used to submit manuscripts to Mr Nakahara. Mr Nakahara was a painter and editor, and he had launched “Soreiyu(Soleil)”, “Himawari”, “Junior Soreiyu” and other magazines for women, but Mr Terayama's manuscripts were not published. Mr Terayama must have been interested in it. I think he knew that, which is why he included Mr Yokoo instead of including me. I also knew the lyrical stuff, the girl's tastes.

Terayama's first book of poems was drawn by a painter and illustrator, Etsuro Suzuki. Etsuro Suzuki was the person who drew the table of contents and other illustrations for Junichi Nakahara's “Himawari”. I later realised that if Mr Terayama asked Etsuro Suzuki to do it, he must have been familiar with culture like Nakahara..

The quintessence of Akira Uno

ー You worked on the stage and advertising art for Tenjo Sajiki's performances in the 1970s. Since 1996, you have been the artistic director of the Dance-Element Kozue Saito Ballet Studio, where you are also the artistic director. In such stage design work, do you look at it from a designer's point of view?

Akira I guess it's a kind of design perspective, but I sometimes come up with ideas that can be seen as visual scandals, such as the idea that it would be interesting to suddenly see a giant snail in a place like this. I create landscapes and scenes that are not in the book. I was involved with Dance-Element for about 20 years, and I even wrote the script for the second half. I like to create tricky, theatrical and scandalous scenes, such as burning a house made of cardboard, or using smoke and lighting to make what I thought were stairs peel off and dancers come out of them one after the other. Basically, maybe it's in my whole thing that I want people to say 'ah'. I dare to put in a snail that people would say, "I don't want to see a snail". You could say it's a technique to get people to take notice for a moment, but I think it's probably based on the fact that I want to create strange and improbable situations.

ー The visual scandal makes it more attractive, doesn't it?

Akira With this title, I have the idea of wanting to surprise the people who come with this image or surprise them.

The influence of illustrations

ー İn this exhibition, too, many young people visited, with illustrations being used by musicians such as Ringo Sheena's 2013 album “Ukina” and Kokushoku Sumire, as well as collaborating on the 2017 film “Mary Shelley”. What makes it possible for you to continue to make an impact? Perhaps it is difficult for you to talk about this.

Akira It's not so much that it's hard to talk about, but rather that you don't understand. My interest in illustrations started when I was a child. The war ended when I was in the sixth grade of primary school, but I grew up in a miscellaneous culture, such as “Kurashi no Techo”, Junichi Nakahara's “Himawari”, “Soreiyu”, “Junior Soreiyu” and “Shonen Club”. My mother ran a coffee shop before the war, so we also had a collection of newspapers and magazines from various companies that she prepared for her customers.

One of the pictures I remember is. A man called Sohachi Kimura (Western-style painter, printmaker and essayist) had illustrated Seiichi Funabashi's “Hana no Shogai”(Life of Flowers). It is a period novel, but there are good women in it. She is a chic woman who plays the shamisen and teaches kouta (short songs). There, a man sings, "In red, a kanjo's hakama and scarlet carpets, seven days a month," in script. There is no sequence in the novel where he teaches kouta at all. Now I think that Mr Funabashi did not write the manuscript and he came up with the idea on his own and Sohachi Kimura drew it. I think I was around junior high school when I saw it. It's like a riddle, isn't it interesting that he called a woman's period seven days a month? It's also somewhat modern. I think it was a newspaper, but I was shocked because it was allowed to depict such an indecent thing. I think a percentage of this surprise also led to my desire to draw illustrations. I also write characters in Japanese characters. Like when the clingers say "teme-e". The effect is that the dialogue gives it personality. So I like writing characters.

Also, a novel by Bunroku Shishi called “Jiyu Gakko” (Free School) became popular and was made into a film by Shochiku and Daiei based on it. The Shochiku version starred Shin Saburi, but the novel was illustrated by Shigeo Miyata, a doctor and painter, who drew a slightly obese man. When I thought that his image was different from that of Shin Saburi, Daiei invited applications from the public to match the picture. At that time, I thought that the influence of the illustrations was amazing.

ー So it was an event that had such an impact that you still remember it in detail.

Akira From then on I copied various illustrations into my notebook, and when I had accumulated two or three notebooks, I thought, what should I write on their covers? I looked it up in the dictionary and found out that illustration means illustration, so I wrote it in. In fact, in the complete works of Sohachi Kimura, the word 'Illustration' was written in English. It was only much later that the term illustration became popular in general.

ー I was in junior high school, and it's amazing that my passion remains fresh and continues until I'm 88 years old. I feel that is why it appeals to the younger generation as well.

Akira As an illustrator, there were professionals like Sentaro Iwata, but I felt they were too professional and not interesting enough. I was more attracted to the work of Sohachi Kimura. My school had a design department, and I used to write "zuan" (design), but there was a competition organised by a newspaper company, and as I won prizes for my work in converting it into graphics, I began to feel that design was more interesting than painting. One of my acquaintances was a theatre artist, and when I was asked to do a painting, he said, "Your paintings are too lyrical”. He told me that “lyricism is an act of looking back, considering the future of Japan”. Perhaps it was because the theatre was mostly left-wing, but I was told at the outset that it was not appropriate for creating a reforming Japan in the future. I also felt that design is a translation job, where I am commissioned to say something about the client's ideas and themes on their behalf, so it doesn't matter if it is lyrical or not, and I felt a sense of indifference. This experience made me realise that it is good not only to draw pictures, but also to put people's messages on them. Sohachi Kimura's illustrations were like that.

That's how design became interesting. Around that time, the Nissenbi Exhibition was held in Nagoya, where famous designers such as Yusaku Kamekura and Takashi Kono were exhibiting, and I was very impressed by what I saw. I entered the public exhibition, was selected and became a member of the Nagoya district. But shortly afterwards I came to Tokyo, but I wasn't a member in the Tokyo region, so I applied again as an ordinary designer, got a special selection and became a member of the Tokyo region. I painted several different styles, including realistic, stylised and painterly... I thought this would be a hit. The one that won a special prize was a painting of the ballet “Carmen”, but it was spelt wrong. When one of the selection committee members criticised the spelling, saying that it was wrong, Mr Kono told him that he could fix such a thing. In the end, it was selected for the Special Selection as it was, and I went to the venue to fix it. I think Mr Kono's words were significant.

Mieko Mr Kono was a big man.

Akira Now that I think about it, I liked to change various styles and ideas, so I guess that means I had a kind of snobbish spirit, which is different from becoming a painter and aiming for art.

Nippon Design Centre and Graphic 21 Association

ー After graduating from high school with a degree in design, Mr Uno joined Calpis in 1956 and left in 1959 to become a freelance designer. Around that time, he began helping Kohei Sugiura with his work, and in 1960 he joined Nippon Design Center, an advertising production company. How did you get there?

Akira Kohei Sugiura won the JAAC Award in 1956, and Gan Hosoya and Kiyoshi Awazu also won awards around that time. While we were all getting together, Masayoshi Nakajo, Shigeo Fukuda and Tamotsu Ejima got together at the Tokyo University of Arts and held a three-person exhibition. Mr Sugiura was also at the Tokyo University of Arts, but he was in the architecture department, so he wasn't working with Nakajo and the others. So we would get together at the Sugiura house to hold exhibitions. I respected Mr Sugiura a lot. But we ended up not having an exhibition.

Mieko You couldn't reach a consensus?

Akira There was a 'Graphic 21 Association', and we moved to that. Yusaku Kamekura and Ryuichi Yamashiro were like the bosses, and they met on the 21st of every month at the International House of Japan in Roppongi. If we had any works, we would bring them out and everyone would critique them. One time, Kiyoshi Seike came as a guest because he was going to talk about contemporary architecture. I was invited and became a member halfway through. We went to Byodoin Temple in Uji and discussed Toshogu Shrine. On the bus, the bus guide's microphone would come around and we would discuss things. I was doing things like arming myself with theories.

I now think that this laid the groundwork for the creation of Nippon Design Center. But Mr Sugiura and Mr Awazu said they didn't want to make advertisements and split up. Kazumasa Nagai, Ikko Tanaka, Tsunehisa Kimura and Toshihiro Katayama joined, and almost the entire 21 Association, including myself, joined Nippon Design Center.

There was another World Design Conference in the 1960s, and I think the Design Center concept overlapped with that. Anyway, the two masters were amazing. It was an interesting adolescence with those two planning the project.

ー Tsunao Harada and Tadanori Yokoo would soon leave the Design Center. Then in 1964, you and others formed Studio Ilfil.

Akira But it was dissolved after a year.

Mieko Isn't that your fault?

Akira Yes, it was my fault. We used the sixth floor of a small building in Ginza's 2-Chome district as our office. It was so small that I could hear the toilet, so I had to go to the nearby Matsuya department store to do my business. At the time, Mr Harada was selling well, but Mr Yokoo and I had no work. The job that finally came along was a newspaper advertisement for Max Factor. But the office was too small to spread the newspaper, so we left the office.

ー Max Factor asked you at such an early stage, didn't they?

Akira That was in 1965. I'm not sure if it was a request from Dentsu or if it was Hideki Fujii, the photographer, who suggested I work with them. I think it was an eye make-up campaign. But I didn't have time to shoot, so I chose a picture of a girl from the photos Mr Fujii had taken and put a picture of teardrops as diamonds under her eyes. Printing at the time was made with a coarse mesh, so it didn't look out of place when I drew the picture with a flesh brush. Around that time, I started doing covers for a magazine called “Shin Fujin” (New Woman), and Tsuneo Suzuki was the photographer. I was doing a lot of tinkering with various photographs. The photographers I work with are not afraid to tinker with photographs.

ー It's true, there's a scandal, or rather a surprise there.

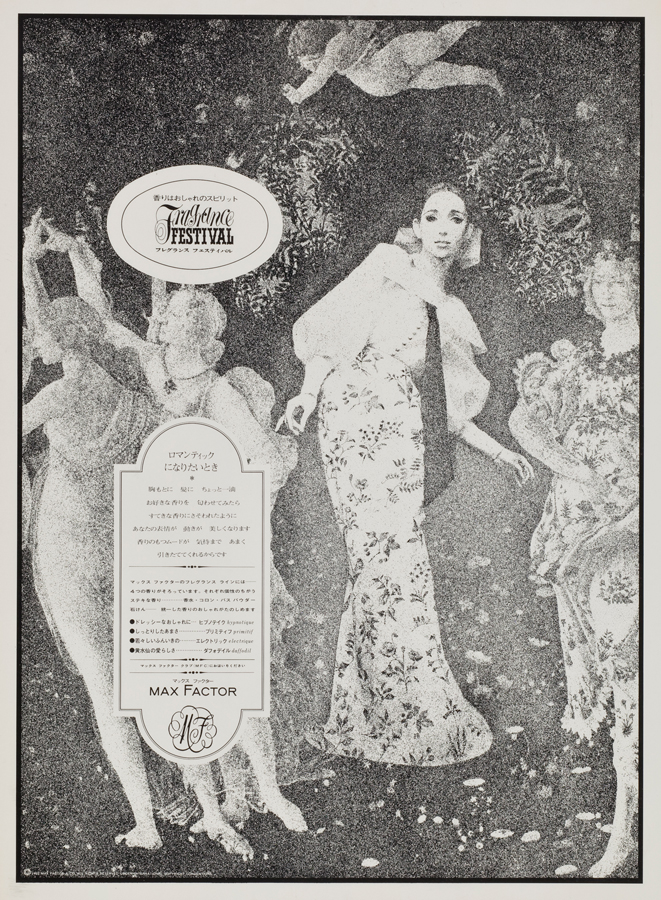

Akira Printing was bad in those days, so we did it with sand-printing, but we photographed the models in the studio with Botticelli's paintings in the background, cut them up and pasted them over the pictures. It doesn't give it away. The mesh dots were a mesh like sandpaper, and we were able to do things that are not possible with today's highly restored platemaking. It was a time when you could do things like Botticellini's plants in dots on the model's skirt, and other painterly things without a care in the world.

Both “Max Factor (Fragrance Festival)” newspaper advertisement proofs (1965). The right depicts a teardrop diamond, while the left is processed from a Botticelli painting, giving the paper a surprising appearance. Collection and photographs courtesy: Kariya City Art Museum

ー The 1970 performance of “Baron Brabra”at Korakuen Amusement Park, performed by the Tenjo Sajiki, also attracted a lot of attention.

Akira I wanted to do something different from what most people think of advertising. I have always wanted to surprise people.

ー I think that's what the client was expecting when they commissioned you.

Akira I think they liked my first job.

Mieko Max Factor also told you to do whatever you wanted. That's what they did with “Joie Joie”.

Akira Usually the campaigns were planned at the head office in the US, but I would redraw the logos. For the project in Japan, I got Kazumi Yasui (lyricist) involved and asked her to do something. I changed the English word Joy to French and called it Joie Joie, and we did a campaign.

ー Your work and encounters in the 1960s and 1970s laid the foundations for her later work. Looking back, who do you think were the most important people you met?

Akira That would be the three photographers. First of all, Tsuneo Suzuki. He was on the cover of “Shin Fujin” for six years. Hideki Fujii for Max Factor. Then there was Hiroki Hayashi of “Hanashi no Tokkushu”. They all died early.

ー The photographs and then Mr Uno's illustrations and designs made them even more surprising. I think it is because of the impact of your work that it is still used frequently in special exhibitions. It can be said that the Kariya City Art Museum had the foresight to approach you at an early stage. I would definitely like to cover the museum as well. Today's talk was also a valuable historical testimony about design and illustration. Thank you very much for today.

What is the Kariya City Museum of Art Archive?

The Kariya City Art Museum in Aichi Prefecture, which opened in June 1983, aims to build a collection based on modern and contemporary art from Aichi Prefecture and other regions, in line with its role as a regional public art museum.

Akira Uno, who was born in Nagoya City, Aichi Prefecture, was the very object of the collection, but the museum also collects 'post-war art' by artists who developed avant-garde activities after the war, 'contemporary art' by artists contemporary with the museum, from original paintings to picture books, magazines, advertisements and posters, and there is overlap in these three areas. The overlap in these three areas also shows the importance of Uno's collection to the museum. The museum's archive of just under 600 of Uno's original drawings and posters is available on the Database of Collected Works and other websites. From 2022 onwards, Uno is said to have asked the museum to organise archive material relating to his activities up to recent years, and to be concentrating on researching his works. The museum's Uno collection is expected to grow in size and weight in the future, and we would like to interview the museum again when concrete plans for the future come into view, together with its opinions and know-how on archiving.

Enquiry:

Kariya City Art Museum

https://www.city.kariya.lg.jp/museum/

Kariya City Art Museum, 'Database of the Collection'.

http://jmapps.ne.jp/kariya_art/