Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Riki Watanabe

Product designer, Interior designer

Date: 13 July 2017, 14:00 - 16:00

Location: Jiyugaen Myonichikan

Interviewees: Akira Yamamoto (Akira Yamamoto Design Office, Q Designers staff member)

Interviewers: Aia Urakawa, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Riki Watanabe

Product designer, Interior designer

1911 Born in Tokyo

1936 Graduated from the Wood Craft Department of the Tokyo Higher School of Arts & Technology (currently Faculty of Technology, Chiba University). After graduating, he joined the Gunma Prefectural Kogeijo and studied under Bruno Taut.

1949 Founding of the Riki Watanabe Design Office.

1956 Katsuo Matsumura and Yu Watanabe join the firm and the name is changed to Q Designers.

2013 He passed away.

Description

Description

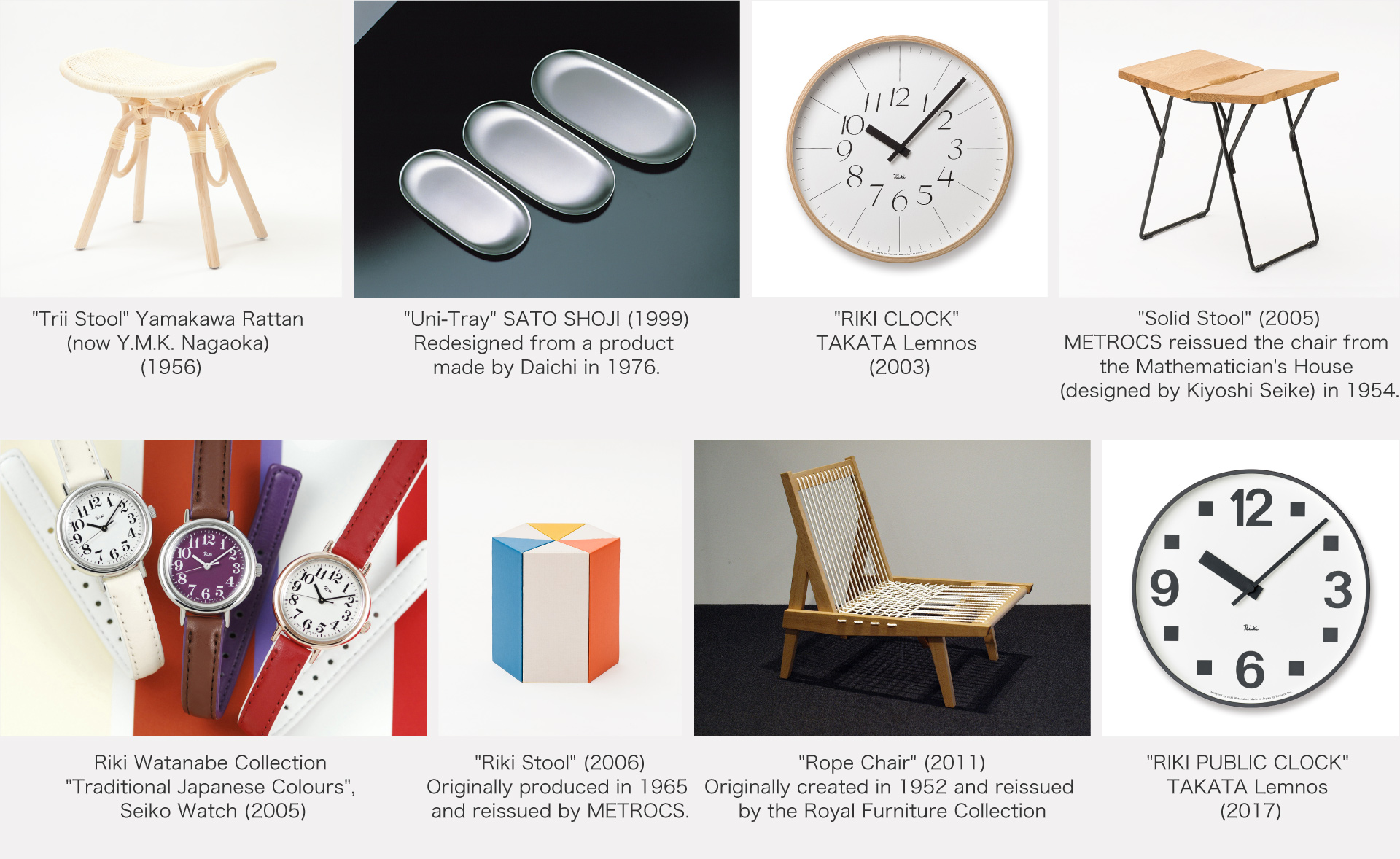

In 1949, shortly after the war, he set up his own private practice and became a pioneering freelance designer, laying the foundations for the Japanese design world in the 20th century. He was the first director of the Japan Industrial Design Association (JIDA) in 1952, founded the International Design Committee (now the Japan Design Committee) in 1953 with Masaru Katsumi, Isamu Kenmochi, Kenzo Tange and Sori Yanagi, and in 1959 founded the Craft Center Japan with Masaru Katsumi, Tatsumi Kato, Junshiro Sato and Takeo Yoshida. In 1966, he participated in the opening of the Department of Interior Architecture at Tokyo Zokei University. He is also known for creating many innovative products that embodied democracy in the still poor post-war years. For example, he designed the "Rope Chair", a low-cost chair that could be used in conjunction with a zabuton (a Japanese cushion), to bring chairs into homes where tatami mats had previously been the norm. It was designed as a small, inexpensive wall clock that could be used in a small house in Japan. For more than 50 years he has been working with the architect Kiyoshi Seike on the interiors of many houses and furniture, including experimental furniture such as bookshelves that seem to float in the air and mobile tatami mats. Since the 2000s he has been involved in the design and development of watches, including the Riki Watanabe Collection for Seiko Watch and the RIKI CLOCK for TAKATA Lemnos. In addition, METROCS reissued some of the products they had previously worked on, such as the Solid Stool made for the Mathematician's House, a house designed by Kiyoshi Seike, and the Carton Furniture, an assembled piece of furniture made from paper. In 2011, the Royal Furniture Collection reissued "Rope Chair" to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth. This is proof of the timeless universality of Watanabe's designs.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Products

"Rope Chair" (1952); "Torii Stool" (1956); "Round Table" (1956); "Riki Bench" (1960); "Caslon 101" (1964); "Riki Stool" (1965); "Small Wall Clock" (1970); "Pole Clock at Dai-ichi Seimei Building" (1972, now DN Tower 21, Hibiya, Tokyo; "Uni-Tray" (1976); "RIKI CLOCK" (2003); Seiko Watch "Riki Watanabe Collection" (2000-)

Furniture for residential and commercial premises

"Usagi Kindergarten" designed by Kiyoshi Seike (1948); "House of Assistant Professor Saito" designed by Kiyoshi Seike (1952); "Mathematician's House" designed by Kiyoshi Seike (1954); "SH-1" designed by Kenji Hirose (1953); interior and furniture of "Briand", the main bar of Keio Plaza Hotel (1971); "St. Paul's Church" designed by Nippon Sekkei; small chapel and chairs (1974); "Karuizawa Prince Hotel South Wing" designed by Kiyoshi Seike (1982)

Books

"sobyou, Watanabe Riki", The Japan Institute of Architects (1995)

"Herman Miller monogatari: Eames ha kokokara umareta", Heibonsha(2003)

Interview

インタビュー

I think it's important in an archive to pass on the ideas of the designer as well as the product.

Hotel interior design in the late 80s.

― Did you work for Q Designers before?

Yamamoto After graduating from university, I had decided to go to Italy to study, but I had about six months to spare and was thinking of getting a part-time job when my professor introduced me to the firm.

From the first time I met Mr. Watanabe, for some reason he took a liking to me, and Mr. Shinsaku Mizuno, the head of the office, said to me: "Never before has anyone taken such a liking to you". Maybe he felt closer to me because he knew we went to the same university and high school. He was 75 years old at the time and there were about eight of us in our 30s to 50s. The office was busier than it had ever been since it started, and I had to work overtime and on weekends.

― What did you do for Q Designers at that time?

Yamamoto My work was mainly in interior design. One of the biggest projects was the Prince Hotel, which was built every year in different parts of the country and abroad. The architect Mr. Kiyoshi Seike designed the building and Q Designers designed the interior of the rooms, restaurants and bars. We also worked on showrooms for Hitachi and INAX (now LIXIL), interiors for dental clinics and travel agencies, and exhibition stands.

― Not long after that, you went to Italy to study.

Yamamoto I was in Italy for about seven years, two years at the Politecnico di Torino, and then I worked for Mr. Shigeaki Asahara and Raymond Architectural Design Office in Turin. During that time I came back to Japan three times and each time I went to see Mr. Watanabe, he always welcomed me and even invited me to dinner. While I was in Italy, I corresponded with the people in the office, and then I found out that Q Designers had been dissolved and the office closed down. After I returned to Japan in 1994 and started working freelance in 1995, I didn't see Mr. Watanabe or anyone from his office for a while, but in 1997 I heard about a series of exhibitions by him, Mr. Sori Yanagi and Mr. Daisaku Cho at the Living Design Center OZONE in Shinjuku, Tokyo. So I decided to go to the opening. When I saw Mr. Watanabe there, I greeted him and he was very happy to see me. I gave him my contact details and he asked if he could help me with some work. The firm was dissolved, but he continued to work on his own.

I first helped him to redesign a stainless steel tray for Daichi, which he had designed in 1976, as the "Uni-Tray" for SATO SHOJI, and then to design a watch for Seiko. The wristwatch design in particular was a first for him, and although he started off not knowing how it would turn out, it was a big hit when it was launched. The TAKATA Lemnos wall clock, which he designed later, was also a big seller. I think he trusted me even more after I helped him with those hit products, and I supported his work until he passed away.

He didn't want to leave things behind because he didn't want to see his past work.

― Do you know where Mr. Watanabe's design archive of drawings, mock-ups and documents, including those from his later years, is kept?

Yamamoto Some of the items were stored in a storage room in the office and a few in his home. After he passed away, his family took some of the things he was attached to, and the drawings, furniture and large photographs used in the exhibition were kept by Mr. Yuji Shimotsubo, the head of METROCS, at his company. Mr. Shimotsubo has helped me in many ways. I was given an Eames "rocking chair", Eero Saarinen's "Tulip Chair", USM Haller's system shelves and books from Mr. Watanabe's home.

― I heard that when he was over 90 years old, he started to bring various things to Mr. Shimotsubo at METROCS, saying, "Don't you want this? Did you also receive anything from Mr. Watanabe?

Yamamoto At that time he told me that he had started to organize his house, and he was getting rid of things little by little. I was given Eames books, toys, design magazines, posters, etc. He said to one of the people at Seiko, "Please use this as a reference for the colours of your watches" and gave him a big thick book of traditional Japanese colours. Traditional Japanese colours are as diverse as the layers of kimono that change with the seasons, and the names of the colours are very emotional. This inspired Seiko to create a series of traditional colours, which was very well received.

― Did Mr. Watanabe talk about his archive before his death?

Yamamoto At least when I was working in the office and helping him in his later years, I never heard of him. He said he didn't want to look at his past work, he didn't want to keep too many things. He said it was because looking at his past work made him feel depressed, because later he would worry about what he should have done. So, although he had a lot of design products in his home, most of them were made by other designers. When I first heard about his solo exhibitions at METROCS in 2005 and at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo in 2006, he was not at all interested. He was adamant: "I don't want to dig up the old stuff, there's no point in doing that, there's no exhibition". However, people of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo and Mr. Shimotsubo of METROCS were very enthusiastic and consulted with Mr. Watanabe many times, and persuaded him to do it because I would help him, and we managed to hold the exhibition. Many people came to the opening and asked for his autograph, which made him very happy. In his later years he had a clock in his home which he had designed himself, and he also wore a watch.

― Did the experience of the retrospective change his views on the archive?

Yamamoto There seemed to be no particular change.

He did not make many sketches and very few models.

― Then he wouldn't have been left with anything like a rough sketch before he started drawing.

Yamamoto Mr. Watanabe may have made sketches when he was younger, but he was not much of a painter to begin with. Mr. Makoto Inada said that he had a small sketch of Mr. Watanabe, who had been supporting him in furniture design for a long time in his office. I remember the two times I saw Mr. Watanabe drawing, his hand was moving very fast, bleeping, and he never stopped his lines, even the corners of the furniture had the momentum of lines crossing each other.

At the Tokyo Higher School of Arts & Technology (currently Faculty of Technology, Chiba University), where he attended, he was taught that he should not use ordinary industrial drawings. It was important to use strong and weak lines and to convey a feeling. I think it's partly because of that, but also because the lines he draws have a certain flavour, a touch that's very different from the descriptive lines of other people.

― When he was designing watches in his later years, did he ever make any sketches?

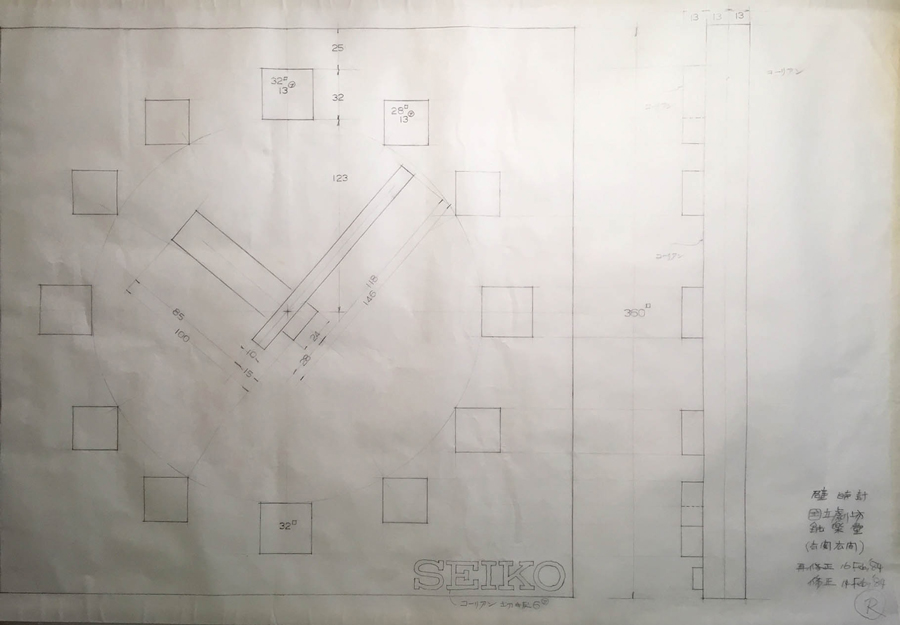

Yamamoto He didn't draw the sketch then either. I used to draw the drawings on the computer. At the beginning of a watch project, he would bring something that he had designed in the past, or something that he had used as a reference, and he would say, "This is what I have in mind. He would give me a drawing and I would show it to him, and he would give me detailed instructions on how to do this and that, and then I would revise the drawing over and over again. So we would make a huge number of drawings. He was very particular about the type, size and balance of the letters, and he had lots of actual and enlarged design drawings to work from. For the clock project, he was very passionate about the design of the dial, including the hands.

― Did he make any prototypes or models?

Yamamoto When I was working in the office, most of the work was interior design, so there were a few architectural interior models, but I had never seen any kind of prototype of a product. The only thing we had in the office was a small model of a pole clock in Hibiya.

One day, he said to me, "I drew this three-dimensional drawing, so Mr. Yamamoto, please make something like a model", so I made a model of a wine cooler, which was supposed to be made of Spanish mackerel, which is used for rice tables. I put resin putty on the foam, but he said in his old craftsman's language, "Wow, you scraped it with a spatula! He was impressed with the way I made it.

― He has written a book, but is there any manuscript left?

Yamamoto I don't think any of his original manuscripts have survived. I have a few of his letters. He was a man who wrote a lot. Once he wrote to me and said, "I have something to do, please call me". It's funny, isn't it?

He was a design educator for half of his life, and he was a frequent contributor to newspapers and magazines. I think some of his articles are still there. For example, he was one of the first to write a newspaper article about the designer's responsibility for an accident caused by a pedestrian's clothes being caught on the end of an L-shaped door handle because it was pointing in the direction of travel. When the quality of the wood of a piece of furniture he had designed was changed without his permission, he denounced it in a design magazine as non-negotiable, and insulated himself from the manufacturer. I once wrote a long, anonymous rebuttal to his appeal for donations for a monument at his alma mater, which he wrote out of righteous indignation, and which I corrected on my word processor and posted in the mail. Looking at it now, it may have been excessive or misunderstood, but I think I dared to say it to raise awareness of design, and I also think he was a harsh person who did not hesitate to correct things.

A survey tracing the archives of Riki Watanabe.

― Do you still have any clippings of him from magazines or newspapers?

Yamamoto He wasn't interested in it, but it seems to have been recorded in the office. I have also seen a notebook which describes the history of the office in great detail, including the comings and goings of the staff. After the office was dissolved, it was scattered, but Mr. Takanori Shinohara, who was a member of the office, has kept a scrapbook with clippings of articles and pictures of the interior. There are three large ones and two small ones. Thanks to these scrapbooks, I was able to follow the chronological development of the products to some extent when I was organising his exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. Now I'm borrowing the scrapbook and I'm documenting it with photographs. I've been borrowing it for almost a year now, because there are so many of them.

― Did you borrow it because you wanted to organise some kind of archive?

Yamamoto I'm trying to document it to the best of my knowledge. I'm documenting it with photographs and trying to find out where the work is and put it together in such a way that if someone goes there they can see it. As for the clocks, I'm researching them not only for the archive, but also to see if I can use them in my future work for his series.

After he passed away, I was sorting through his home and the storage room in his office and found some new drawings, photographs and other documents. He was not a man who left things behind, so I think that he might have liked them or wanted to rethink them, or had some other intention in keeping them. In archiving them, I am also trying to guess and decipher his thoughts, which sometimes reveal facts that were previously unknown.

For example, I found a drawing of the clock in the National Noh Theatre, and when I explained the situation and asked to see it, it turned out to be the same one on display as in the drawing.

He had a lot of negatives at home, so I had them sent to the lab and I found about four different prototypes of public clocks, like the ones you see in city parks. I asked someone at Seiko, who knew about the old days, and he said that they must have been designed by him. I also found out from talking to a relative that the pendulum clock in the lobby of the Export-Import Bank of Japan (now the Japan Bank for International Cooperation), which had not been recorded, was also designed by him.

In the warehouse I found a full-size A0 blue print of "Rope Chair". Blue prints fade when exposed to the sun, but thanks to the fact that it was folded and stored in a dark place, it was relatively bright and beautiful. I thought it was important to preserve them as well, so I asked Seiko Epson to convert them into data using a fine scan and make high-quality prints, which I keep with the blue prints.

The other documents, such as magazine articles and letters, are being collected and organised little by little by his son-in-law, Mr. Jiro Tsukada, who has a deep knowledge of archives and has translated and published many of them.

― Do you set deadlines for your archive research?

Yamamoto I don't really think about it. I don't do archival research every day, but when I find something in the drawings or negative films, I go to the site to investigate and record it. I basically hope to use the data for his future work in the series, but on the other hand I feel that I am on a mission to keep these records in good order.

I think it's important to keep not only the product but also the designer's ideas in the archive. In fact, I think that the newness and excellence of ideas and philosophies are more important in design than the form. Unfortunately, when a person who is a strong artist works almost alone, if it is not talked about after his death, it will be forgotten by the public.

― It would be ideal to have someone like Mr. Yamamoto, who represents the ideas of the designers while using their archives in a contemporary way.

A passion for watch design in his later years

― By the way, did he have a personal collection?

Yamamoto Mr. Watanabe was particularly fond of marine clocks, the water-resistant clocks on ships. He said that he wanted to have a collection of them, and he had three marine clocks in his home, which he had acquired in a second-hand shop. During my time in the office I saw a pile of marine clocks he had designed for Seiko in the warehouse. When he heard that they were going out of production, he bought all the stock and gave them away to anyone who was interested. At the time I didn't appreciate marine clocks, so I didn't get one, but now I regret it very much.

He was also fond of pocket watches belonging to railway drivers. He said, "That was one of the origins of my design. Nowadays all railway clocks are digital.

― It is well known that Mr. Watanabe designed a lot of watches, but I don't think that his love for watches has been mentioned in many critiques, so this is a valuable story. It must have been a great pleasure for him to be able to use his love for watches in his later years.

Yamamoto I think he used to design clocks for parks, airports, National Noh theatres and other public spaces, but he gradually started to do less and less of that kind of work, and I think when I joined his office it was at the end of his career.

After that, he continued to design watches, even if they were not intended for commercial use, and he had some exhibitions at MATSUYA GINZA. At the end of the 90's, he wrote in a magazne that "I want to try my hand at watch design again" and that "this is one of my life's work".

In this context, it is interesting that Seiko reviewed its own archives and "rediscovered" Mr. Watanabe, and that is how the watch business began. I think he must have been very happy in his later years, because he was able to do a lot of work on watches and they were still a big hit.

― Mr. Watanabe is also interested in children's play equipment, and in 2006 there was an exhibition at MATSUYA GINZA called "Toys for Young Children", which was curated by Mr. Watanabe and featured a selection of play equipment from around the world.

Yamamoto The only children's playground equipment he had designed was the "Riki stool", but when he was asked to design a watch for children for Seiko, he was very interested. When I had a child, he gave me a silver rattle that he had selected for an exhibition at MATSUYA GINZA. He was also interested in Scandinavian building blocks.

He also took good care of his grandchildren. There was a series of articles in the newspaper about his daily life, mostly about his work, but also about his daughter's visits home. "The ladies were totally unreliable, so I did everything for them, from bathing to everything else", and how he enjoyed having his grandchildren at home and missed them when they left. The article is probably still in my house.

It's not about the past, it's about the "present".

― Lastly, I would like to ask you about your own thoughts on the Design Museum. Even if it is from the point of view of the fact that you are actually Mr. Watanabe's archivist yourself.

Yamamoto So far I've only been able to take photos and keep track of what's there and where. I'm only able to do this because I want to use it as a basis for my future work. If I hadn't done that, it would have been very difficult to motivate myself.

After he passed away, we had many discussions with his family and Seiko Watch, we decided that his watchmaking philosophy was universal and should be passed down from generation to generation, so the RIKI series was continued and directed by me. Since watches have always been very much a part of fashion and trends, he has always enjoyed incorporating the ideas of others. Hopefully we can keep the emphasis on his philosophy of life and the elements that remind us of something Riki Watanabe, while changing the design to suit the times. On the contrary, TAKATA Lemnos clocks are very strictly reprinted, except for the arrangement of the size and materials to match the modern times. We have recently reissued a number of clocks, such as the public clock I mentioned earlier, and there are still others under consideration. These two pillars support the RIKI brand of watches, and perhaps make it possible to create a kind of archive of products that still exist. Well, I can say that while it's still selling.

At the moment I'm mainly researching watches, but I think I need to record other things as well.

― Do you have a vision of what you would like to see in a museum? Do you have any ideas about what kind of museum you would like to visit, or do you think it would be useful for your work?

Yamamoto In architecture, I am more interested in the initial sketches than in the actual drawings. I think it's better to have a collection of the initial inspiration and the final form. If the facility is to display only the things that have been made, it is like a gallery, and if it is to be called a design museum, I would like to have some more ideas.

It would be nice to be able to see how clocks are used in households all over the world, not just in the past, but in the present. That's something we can't even look up on the internet. It may be a little different from the point of view of a design museum, but that's the kind of information I'm interested in.

― But isn't it interesting that you are now investigating the archives, because you have made some discoveries that were not known before?

Yamamoto More than other designers, it's interesting to investigate and discover things about him that we don't know. It's not only interesting, but I always try to think about the possible connections between this product and this company. By expanding in this way, I hope to make Mr. Watanabe's ideas known to as many people as possible, so that they can be passed on to future generations.

At the moment, I am mainly researching watches, but I hope to spread the word to people who have never heard of him before, so that they will be interested in his other products.

There are already many good products in the world, but it is difficult to sell them nowadays. I think it's important to communicate the idea, not the product. It's also important to find a way to communicate.

― I think that today's talk about how archives will live on for future generations, even though they are often left to die, will be helpful to many people. Thank you very much for your valuable talk.

Drawing of the clock of the "National Noh Theatre" (1984) / Meeting at Seiko Watch Mr. Watanabe and Mr. Yamamoto (2005)

Enquiry:

NAkira Yamamoto Design Office

e-mail:ayamamot.35426@gmail.com

Metropolitan Gallery

http://metropolitan.co.jp