Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Ikko Tanaka

Graphic designer

Date: June 13, 2019 10:00 - 12:00

Location: DNP Ginza Building

Interviewees: Hideyuki Kido (General Manager, ggg/ddd Planning Office, DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion),

Hanayo Mikami (Business Planning Office, same as above)

Interviewer: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

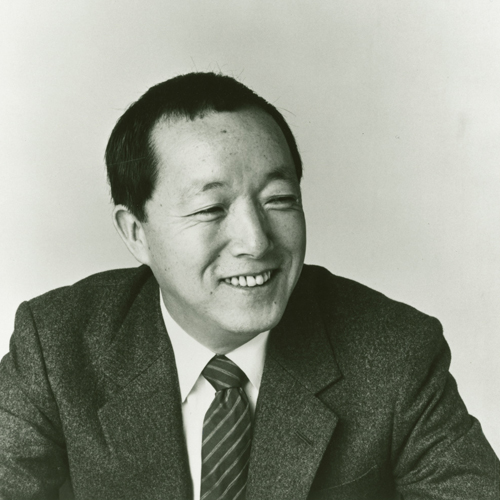

Ikko Tanaka

Graphic designer

1930 Born in Nara Prefecture.

1950 Graduated from Kyoto Municipal College of Fine Arts (now Kyoto City University of Arts) and worked for Kanegafuchi Boseki (now Kracie Holdings).

1952 Worked for Sankei Shimbun.

1953 Member of Japan Advertising Artists Club.

1957 Worked for Light Publicity.

1960 Participated in the founding of Nippon Design Center.

1963 Established Ikko Tanaka Design Studio.

1975- Appointed Creative Director, Saison Group.

1980- Appointed Art Director, MUJI.

2000 Commendation for Cultural Merit.

2002 Died of acute heart failure (age 71)

Description

Description

The sudden death of Ikko Tanaka in 2002 sent shockwaves through the design and industrial world as well as the graphic world. Tanaka sublimated Japanese moulding, colours and textures reminiscent of the Rimpa school into modern design, and his imposing and graceful style won him international acclaim. As a designer, he moved from Osaka to Tokyo in step with Japan's post-war recovery and became a member of JAAC, honing his skills at the pioneering Light Publicity and Nippon Design Centre before establishing Ikko Tanaka Design Studio. During this time, he also participated in national projects, designing the medals for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and the exhibition design for the Japanese Government Pavilion No.1 at the 1970 Japan World Exposition (Osaka Expo). He was right in the middle of the Japanese graphic design world.

In the 1970s, at a time when design leadership was shifting from the state to corporations, he was appointed creative director of the Seibu Group, and together with Seiji Tsutsumi, he built the Seibu-Saison culture, which led the culture of the 1970s and 1980s. In the early 1980s, on the eve of the bubble economy, he planned and realised MUJI as an alternative to consumer society. MUJI has now grown into a global brand with operations ranging from household goods and foodstuffs to housing and hotel business. At the same time, Tanaka produced venues for designers to present their work and socialise, such as Tokyo Designers Space, Ginza Graphic Gallery and TOTO Gallery MA, and worked to improve Japan's design culture and the status of designers.

Tanaka's greatness lay not only in his creativity. Talented people of his time were attracted to his surroundings. These included, of course, designers, but also Seiji Tsutsumi (deceased), who built a generation as a business manager, clothing designer Issey Miyake, curator Kazuko Koike, architects Kiyonori Kikutake (deceased) and Tadao Ando, photographers Ken Domon (deceased) and Kishin Shinoyama, painter Tadanori Yokoo, textile designer Hiroshi Awatsuji (deceased), designer Shiro Kuramata (deceased), Masakazu Izumi (deceased) of the Urasenke school, to name but a few.

Here, we spoke to Hideyuki Kido and Hanayo Mikami of the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion, which holds the archives of these great designers, about the current state of the Ikko Tanaka Archive and the Design Archive.

Masterpiece

Masterpie

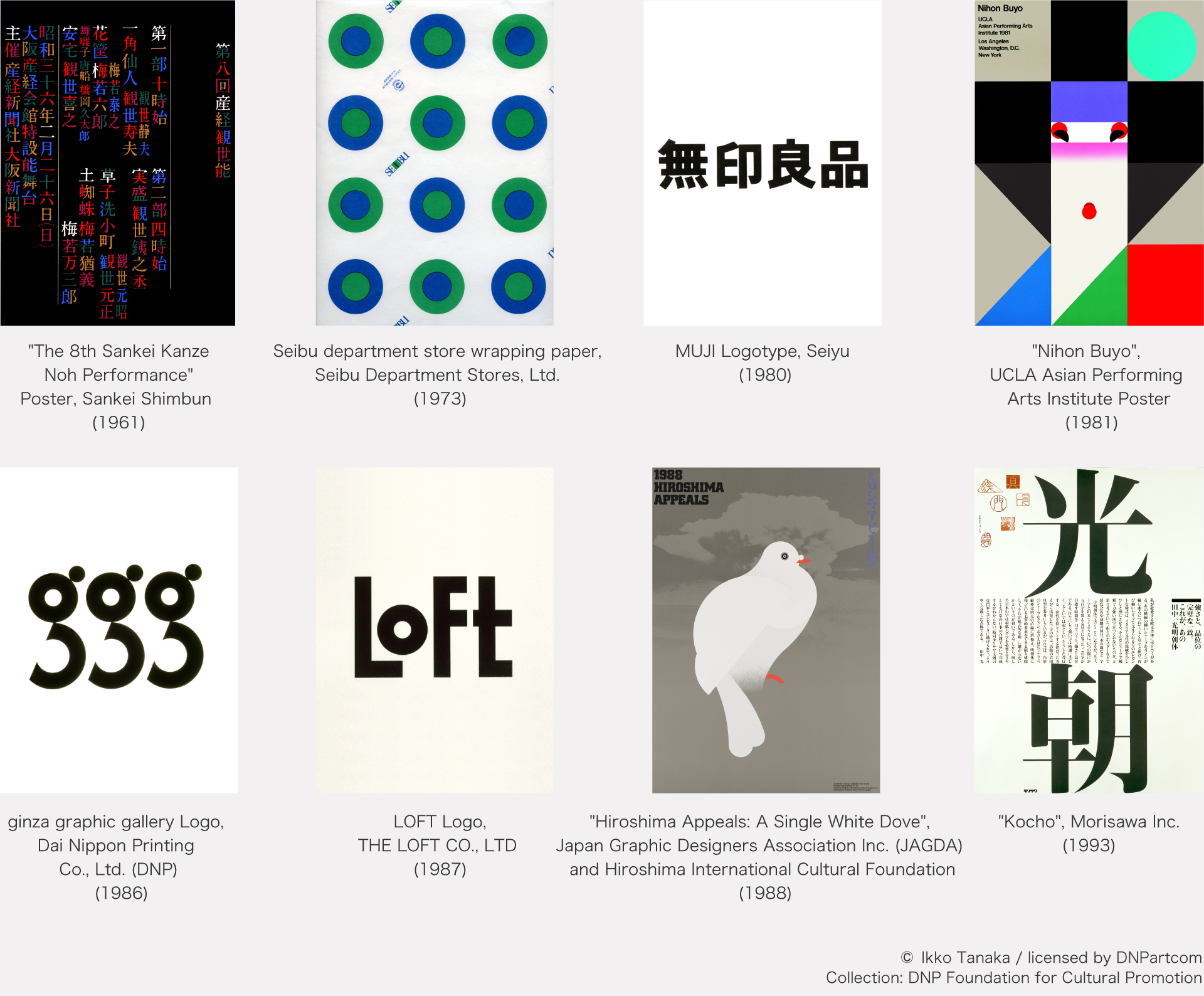

Poster

"The 5th Sankei Kanze Noh Performance", The Sankei Shimbun Co., Ltd. (1958), "The 8th Sankei Kanze Noh Performance", The Sankei Shimbun Co., Ltd.; Osaka Shimbun Co., Ltd. (1961), "Wake Atte,Yasui (Inexpensive with Reasons)", MUJI (1980), "Nihon Buyo", UCLA Asian Performing Arts Institute (1981), "Japanese Poster: Japan", The Japan Graphic Design Association Inc. (1986), "Hiroshima Appeals: A Single White Dove", The Japan Graphic Design Association Inc. and Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation (1988), "Issey Miyake A-UN", Issey Miyake (1988), "Kocho", Morisawa (1993).

Logo

MUJI Logotype, Seiyu (1980), The International Exposition, Tsukuba, Japan, 1985 (Science Expo-Tsukuba '85) Logo (1981), Saison Group Logo, Saison Group (1982), ginza graphic gallery Logo, DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion (1986), LOFT Logo, THE LOFT CO., LTD (1987).

Graphic Design

Packaging paper materials for Seibu Department Store, Seibu Department Store (1973).

Main Publications

"Japanese Coloring (co-composition with Kazuko Koike)", Libroport (1982), "The Design World of Ikko Tanaka", Kodansha (1987), "Tanaka Ikko Dezain no Shuhen (Ikko Tanaka Around Design)", Hakusuisha (1989), "Tanaka Ikko Dezain no Shigoto Dukue kara (Ikko Tanaka From the design work desk)", Hakusuisha (1990), "Ikko Tanaka and Future/ Past/ East/ West of Design", Hakusuisha (1995).

Major Awards

Japan Advertising Art Member Award (1954), Warsaw International Poster Biennial Silver Prize (1968), Mainichi Design Award (1973), New York ADC Gold Prize (1986), Tokyo ADC Member's Highest Award (1986), Mainichi Art Award (1988) (1995-96), the First Kamekura Award (1999), the Minister of Education's Art Encouragement Prize (1980), the Medal with Purple Ribbon (1994), the Asahi Prize(1997), and the Cultural Merit Award (2000).

Interview

Interview

The most interesting part of the archive is the letters, photographs, drawings, etc., which give us clues to the personality and ideas of the person.

Current Status of the Tanaka Ikko Archive

― In 2016, we asked Mr Eishi Kitazawa about the archival activities of DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion. This time, we would like to ask you to talk about the Ikko Tanaka Archive. First of all, please tell us about the background of its establishment.

Kido Ikko Tanaka passed away suddenly in January 2002. The staff of the Ikko Tanaka Design Studio stayed on for a while to continue their work, and when they had finished, the office was closed. After that, his sister legally took over the office, and his works and materials had been untouched for almost six years, but we were approached by the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion to take over everything. His sister and brother and I signed a contract and in 2008 we established the Ikko Tanaka Archive at the Center for Contemporary Graphic Art (CCGA) in Sukagawa, Fukushima Prefecture.

― What items were left behind at that point in time?

Kido The volume of the collection was enormous, with everything stored on the first basement to the third floor of the Ikko Tanaka Design Studio building being donated. The largest part of the collection was books, including work-related books, magazines and other periodicals, and publications designed by the professor. Other items included correspondence and documents kept by the office, photographs of private and business trips, photocopies of works, sketches, printing instructions, proof sheets and other items related to the design process. Of course, there were also posters and other artworks and their extra stock. A special feature of the collection was Mr Tanaka's collection, gifts from friends and acquaintances, and tools related to the tea ceremony.

― You said earlier that it was a huge amount, but how much was it exactly?

Kido There are approximately 2,700 poster works, 3,600 book design works, 9,500 books, 25,000 photographic materials and 55,000 documents and letters. The approximate volume of material is about 400 metres of extended shelving, 370 cardboard boxes of materials that do not fit on the shelves, and about 50 cabinets of posters and other materials for storage. This is a rough estimate and not the number of items one by one, so the total number of items would be mind-boggling.

― What do you do about storage?

Kido The amount of posters is so large that the CCGA's space is not sufficient, so other warehouses have been rented on a temporary basis. Posters are treated like works of art and are stored in air-conditioned storage, with each poster placed between sheets of neutral paper to prevent oxidation. Photographic negatives and positives, which are susceptible to deterioration, are stored in special boxes that absorb oxidising gases, and are stored in a dedicated space in the storeroom. Other items, such as book design works, library books and documents, are currently being entered into a database and are stored in a storage room in the same environment as the office for easy access.

― I understand that you are also working on creating a database of these.

Kido It is ongoing: as of June 2019, work has been completed on 55,000 items, but the final estimate is that the number will at least double. The art management databases commonly used in museums have difficulty managing miscellaneous materials such as correspondence. We have therefore developed our own database based on the hierarchical description and registration methods used by archive institutions. Since 2017, part of the database has also been made available on the internet.

― What about the digitization of poster works, etc.?

Kido The 2,700 posters have already been digitised in high-resolution. Taking future technological developments into account, the image data is in TIFF format with a resolution of 400 dpi (full-size equivalent), approximately 10,000 pixels on the longest side and 16-bit RGB colour depth. To achieve this accuracy, we also developed our own special photographic equipment. At the same time, we also invited the plate-making technicians and paper company representatives who were involved in the production of each poster to investigate and record the printing information for each individual item. This was valuable information from the perspective of the history of printing technology.

― I went to the CCGA the other day and saw some of the archives and was surprised to see some of Mr Tanaka's oil paintings from his student days. By the way, do you have any materials that trace the thought process behind his designs?

Kido There were a huge number of sketches and memos that gave images to the staff, but the office did not seem to have a policy of organising each and every one of these sketches. As a result, there are many sketches that we cannot determine what they are for and which work they are for, which is an issue for the future.

― What are your archival priorities, if any?

Kido The first step is digitising posters and other works and compiling a database, and work on the main works is almost complete. Some of them are available on the internet. The database of miscellaneous materials other than artworks is still a work in progress and is not yet available on the internet, but such non-public data is also available for researchers to view in the CCGA museum. The metadata to be registered in the database is based on three international standards, including the ISAD(G) (General Principles for the Description of International Standard Archival Documents) of the International Council of Archives, with a view to exchanging and sharing information with national and international institutions in the future, and with the addition of elements specific to graphic design.

― It's a lot of work. How many dedicated staff do you have?

Kido There are no full-time staff, but three members of the foundation, including myself, and two temporary employees working on the database. At the moment, we are busy organising and compiling a database of a huge number of works and materials, and after 10 years we are still in this state and cannot predict when the archive will be completed. It is endless.

― What problems have you encountered in the course of your work?

Kido As I mentioned earlier, international standards, a major challenge is the terminology used to classify and catalogue materials. These tasks require specialist knowledge, but not all staff members have it. For example, when sorting out printed manuscripts, it is difficult for all the staff to correctly classify the materials, such as the clean printing or the designations of plates, as printing technology has changed dramatically since Mr Tanaka's time and there are few people left in charge at that time. Normally, full-time staff with a thorough knowledge of the printing site and technology would be assigned to this task, but unfortunately, due to various restrictions, this is not the case at present. Therefore, we have to take the inefficient method of creating a database and at the same time correcting any errors as they occur.

― To what extent is the work on the archive progressing?

Kido All 2,700 poster works have been digitised in high resolution and metadata entered into the database. Digitisation of photographs and films is also underway. The films deteriorate quickly and many were already faded when we received them, but some 25,000 have already been scanned. The originals are stored in a dedicated storage room and we usually use digital data. As soon as the sketches are organised, we will start digitising them. Tea utensils and works of art are kept in their original state, and the 9,500 books in the collection are stored on shelves.

At the Ikko Tanaka Design Studio, documents and other materials are stored in envelopes for each project, but the contents are yet to be organised. The majority of the contents are faxes and documents. Private letters and other personal correspondence are of high archival value, but there were very few, probably because they were organised by staff or family members. Other items include office vouchers. As is the case in all offices, these documents are not systematically filed and stored at Ikko Tanaka Design Studio either.

― Even so, he would have done his best to ensure that his character was up to scratch, and I have heard that this was passed down from generation to generation to his pupils.

Kido Ikko Tanaka Design Studio had a large number of staff, and I think it was still a special one among the many graphic design offices. One of the interesting parts of the office was the business diary kept by successive generations of staff from the 1960s onwards. This will be a valuable resource and important evidence for future research on Ikko Tanaka.

― When you talk about archives, I think it is important for designers to have their own workplaces.

Kido I think you are right. The Ikko Tanaka Archive keeps some of the furniture from the office, but not the space itself. Now that I think about it, I should have taken photos of the workspace and the area around his desk.

― Are there any other archives of Ikko Tanaka other than your foundation? For example, is it held by his family? I seem to remember that Mr Tanaka owned a tearoom at Lake Yamanakako?

Kido The tea room at Yamanakako, the building is already in the hands of people, but the foundation has taken care of some of the tea utensils and other items. So, we can say that the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion is taking care of what the public can access as the Ikko Tanaka Archive.

Use of the archive

― Do you also lend out works and copies of images?

Kido Yes, I am the contact person, and a separate company, DNP Art Communications, is in charge of copyright and licence management on behalf of the bereaved family. The copyright of Mr Tanaka is held by several bereaved families, but DNP Art Communications acts as the contact point for the external parties.

― It will take some time to complete the archive, but how will the DNP Cultural Foundation utilize it? For example, do you have any plans to hold exhibitions or compile them into publications?

Kido The Foundation regularly organises graphic design exhibitions, so there are opportunities to do so. However, for me personally, the archive's primary role is as a research resource, so I think it is important to provide materials and improve the environment for academic research. If the archive subsequently develops into a publication or exhibition, I hope to be able to help with the lending of illustrations and artworks.

We hope that such opportunities will increase as much as possible. Meanwhile, the Foundation has been promoting Ikko Tanaka research in its own way. In the academic research grant of the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion, which is now in its sixth year, we have established the category 'Research on graphic designer Ikko Tanaka' and have promoted research activities from the viewpoints of educators and researchers in Japan and abroad. In fact, many people have stayed overnight at the CCGA in Fukushima to conduct research and surveys. The results are published and made public in the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion Academic Research Grant Bulletin, which is published annually.

― In view of the current situation in Japan, which is in many ways a sense of stagnation, it is important to reconsider Ikko Tanaka's time and designs, which were on an uphill slope.

Kido While most design history research used to range up to the pre-war period, I feel that recently it has begun to include the post-war period and even the present day. A few years ago, I was contacted by an American doctoral student who was compiling a thesis on 'Seibu/Saison Culture'. He was researching Seiji Tsutsumi and wanted to research the Ikko Tanaka archive, so he went to the CCGA in Fukushima to consult the materials. At that time, I remember being surprised to learn that 'Seibu-Saison culture' would be the subject of research.

― What will it take to make the archive useful for this kind of unique research in the future?

Kido I think it is to promote research from academic perspectives, such as design history and sociology. This is also the purpose of our research grants, but at present we receive many contacts from overseas researchers. Unlike Japan, research in the humanities, which is not directly related to economic activities, is very active in Europe and the USA, and many researchers are interested in Japanese design from a cultural perspective. I am envious of this.

The Future of Design Archives

― I know that there are many graphic designers who have a close relationship with Dai Nippon Printing.

Kido Yes, we have received many stories. We would like to respond to them as part of our social mission, but even the Ikko Tanaka Archive is not yet complete, so we have no choice but to say that it is difficult at the moment. We are well aware that this is a serious matter for the future of the design archive, but we cannot accept it irresponsibly.

― From what we have heard, selection and discarding are very important for design archives.

Kido I think that's right. I feel that there is a mixture of material that should be kept and material that should be discarded in the vast amount of material. We, as non-specialists, cannot make that judgement, so we keep everything, but perhaps we should draw a line somewhere and sort it out. The Ikko Tanaka Archive also contains some scraps of notebooks on which nothing is written, and I am not sure whether these should really be retained.

― What we feel from this research is the importance of having a clear policy on whether to keep 100 of one designer or 10 of 10, as there are limited costs, space and human resources related to archiving. In other words, do we dig deep and improve quality or do we prioritise quantity in a broad and shallow way?

Kido Right. Although from a different perspective, using Mr Tanaka as an example, graphic design is basically a reproduction, so it would be sufficient to keep at least one book that he worked on. Even if we call it a collection, magazines and other books can be browsed at the National Diet Library, and if we divide it into an archive, we can decide that we don't need to preserve everything, but just have a catalogue.

― I heard that Yusaku Kamekura's library was recently donated to Musashino Art University by Recruit Co. In Kamekura's case, his works and materials are stored at the Niigata Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, where he is from, but it was difficult for even a public museum to accept everything, including his books.

Kido We understand its position. The reason is that if the work is not carried out, the goods will end up in a box and will be stored for dead. As the custodians, we have a responsibility and it is difficult for us to accept items unnecessarily. In the case of museums, we can only release items to the public if they are organised. There is the idea of entrusting the materials to researchers and postgraduate students to organise and research them, but in Japan this is difficult in practice due to various restrictions. There is also a systemic challenge in that it is difficult to continue working on a single theme at a public facility because the person in charge changes every few years.

― In this sense, Ikko Tanaka was also fortunate. In addition to Mr Tanaka, you also have Kazumasa Nagai and Shigeo Fukuda's archives here.

Kido For Mr Nagai and Mr Fukuda, only their works are available. Personally, I feel that the interesting thing about the archive is that it provides clues to the personality and thinking of the artist in areas other than their works, such as letters, photographs, drawings and sketches. For those in the Tanaka, Nagai and Fukuda classes, there are already collections of their works and exhibition catalogues, and many of their graphic works are reproduced as posters, so I think it is rather important to preserve materials other than their works.

― What is the minimum you would like the depositor to do as a custodian, given that it is difficult to store any more?

Kido I think researchers are interested in letters and sketches, so it would be good if they were organised in that area. Unlike works of art such as paintings and sculptures, the work of designers (works), not just graphics, are basically reproductions and therefore easier to obtain. Therefore, I would like everyone to pay more attention to letters, documents and sketches. As design work is increasingly digitalised these days, the value of analogue materials is likely to increase.

― That's right. Tanaka's printing materials, such as block prints and proof sheets, are not only an archive of design but also of printing technology, and are valuable in terms of the history of printing technology.

Kido Researchers conduct research based on hypotheses, for which documentary evidence is indispensable. For example, design processes can be read from correspondence, or relationships can be revealed from an unremarkable snapshot. On the other hand, it is a problem because people's relationships are very important from a cultural-historical point of view, but the person concerned and their family may not want to be known. Personally, I think it would be perfect if the designer could leave everything behind and leave a statement of his or her wishes to remain private.

― As was discussed earlier, it would be fun if Mr Tanaka's letters could reveal episodes and relationships that led to the birth of the 'Seibu-Saison culture'.

Kido It really is. At that time, the project was probably proceeding on the basis of a verbal agreement, and there was no trace of a formal agreement on the logo design of MUJI products in the documents we have on file. I wonder if that is just a sign of the times.

― At that time, there was room for experimentation with business ideas among colleagues. I think that is how MUJI started. Shinzo Higurashi, who made the copy for MUJI, also said that he had no memory of having signed a contract.

Kido This episode shows the momentum of that era. For designers who are busy with their daily work, jobs such as organising archives are low on the priority list. In Japan, archives have only recently been recognised. The art world, which has a longer history than design, faces the same problem. For example, not only artists, but also the three art critics, Ichiro Hariu, Yoshiaki Tono and Yusuke Nakahara, have already passed away, and Kunio Motoe passed away recently. In the design world, I wonder what happened to Masaru Katsumi.

― Mr Kido, what do you think the design archive should be?

Kido The most important thing is that public institutions such as museums and universities are involved: at UCLA there is the Institute of Asian Cultures, which has a huge library and archive. In Europe and the US, master's and doctoral students in Asian studies work part-time to create databases. For the students, there is money to be made by studying and researching, and for the institutions, there seems to be a virtuous circle whereby education and archiving work are carried out at the same time.

― Are there any national or international institutions that you refer to for operational aspects?

Kido It is true that we have come this far on our own, individually referring to teachers and other institutions. So, I don't know if our way of doing things is the right way.

― But isn't this the Japanese standard in the graphic design archive?

Kido I am honoured to hear you say so.

Is the core of the Design Museum an artwork or a design?

― I In addition to the Tanaka, Nagai and Fukuda archives, you now have many valuable posters in your collection. Do you have any plans to develop these into a museum?

Kido A design museum should exist in Japan, but it is not something one company can do. Even if we limit ourselves to graphics, it would be too much to cover posters, packaging, signage, editorial and digital graphics such as the recent website. Personally, I would be relieved if a national museum were to be established to systematise the design archive and take over our archive. In these rapidly changing times, it is impossible to predict whether companies will still exist in 50 or 100 years' time, and this is even more so in the case of corporate foundations. In this situation, we will do what we can, but in terms of permanence, I hope that we can hand over to national or public institutions.

― Now, to change the subject, some approaches to design archives focus on individual designers, such as Ikko Tanaka and Yusaku Kamekura, but design is also an anonymous entity by nature. If you look at it from the perspective of the world and society, the majority of design is anonymous design, what are your thoughts on this?

Kido Personally, I think this is true and I am interested in it. I think that this should be recorded and preserved, but it is also an area that is very difficult to preserve.

三上 It is true that we, as a printing company, are the only ones who can do this. The resulting printed material is a valuable resource, and all kinds of graphic work are gathered by printing companies.

Kido Even if it is not possible to keep all the originals, perhaps they should at least be photographed and retained. I think it is possible if a system is established as an internal system, but it would be very difficult to implement. This is because printing companies are basically in the order-taking industry, and the finished product is the customer's property. They have neither the right nor the obligation to do anything about it.

Depending on how you define it, the anonymous design that abounds in the city is a mirror of society; it is important to think about such design in terms of 100 years, and it is necessary to think about it continuously and systematically from an archival perspective. From the perspective of art and design history, designs with a high level of artistry, such as Mr Tanaka's, are the mainstream, but from the perspective of cultural history and the history of civilisation, the essence may lie rather in anonymous designs.

― What is taught in schools is often highly artistic and design-oriented.

Kido Although Tanaka's posters such as "Nihon Buyo" and "Sankei Kanze Noh Performance" are always included in art textbooks for elementary and junior high schools, they were never actually put up on the streets as posters, but rather as 'works' submitted to competitions and exhibitions such as JAAC. But if you didn't know this background, you would think that those posters were put up on the streets. It's a story that is not true.

― Interesting. So you are saying that Mr Tanaka produced his posters as if they were prints, using silk printing.

Kido When a poster produced as a work of art is also a design, it becomes difficult to define aesthetically and philosophically what design is and what the difference between art and design is. Many designers consciously blur this boundary, and it may not be necessary to make a precise distinction between art and design. Mr Kamekura and Mr Tanaka declared that 'design is not the same as art' and worked hard to improve the profession of designer, but they themselves were involved in activities that were as close to art as possible. This trend is not only true of graphic design, but also in other areas of design. After all, many designers may subconsciously seek self-expression without a client. Conversely, Bauhaus design may have been close to art for the people of the time. It would have taken some time for it to be accepted as modern design.

― Right. Consequently, the spirit and vision of the Bauhaus changed industry and design in the second half of the 20th century.

Kido When it comes to design archives, I think we need both the authorial and the anonymous, but the anonymous is hard to come by, so I would like to see people like researchers and curators.

Personally, I am interested in the activities of overseas travellers and bloggers. For them, cool Japan is the chaos of Akihabara, the menus of cafés in Shibuya and the displays in the streets, and perhaps such vernacular and kitsch is cool Japan. Some of them have created a web gallery to introduce Tanaka's designs and Cool Japan on an equal footing, and are sending the information around the world. It would also be interesting to see projects and exhibitions by young curators from overseas.

― Perhaps it was the focus on the anonymity of ‘MUJI' that led Mr Tanaka to work on MUJI in the early 1980s. As a final question, is it difficult for designers who are active today to ask you to keep their work and materials?

Kido We have already received the posters, but it would be difficult to take care of everything. We would like to cooperate with the National Design Museum if it is possible.

― For example, could they be kept for a fee? In fact, the storage space and labour costs are necessary, so the person who keeps the items would have to pay a part of the costs. I think there are designers and families who would like to do this.

Kido We feel that such things need to be considered. On the other hand, if we charge a fee, we have a certain amount of responsibility, and I can't imagine how much we would be able to handle if we were to take care of them. Currently, we are volunteers, so we can work at our own pace and take our time.

― Is there anything that can be done before a public design museum?

Kido As I mentioned a little earlier, an international network for the commonisation of archive metadata is gradually being established. In Japan, too, archives have recently been attracting attention, so I expect that the sharing and porting of archives held by various institutions and organisations will progress.

Since 2015, as part of the Agency for Cultural Affairs' model project for the formation of archive centres, Musashino Art University has overseen product design, Bunka Gakuen University of fashion design and Kyoto Institute of Technology of graphic design, and there is a movement to examine methods of collecting, organising, storing and restoring works and materials, and to develop a design The curators of the museums with collections were also involved in the discussions. However, it seems difficult to standardise as each museum's staff member has their own way of creating databases and organising materials. Also, perhaps because the concept of archives is new in Japan, there are different ways of understanding 'collections' and 'archives'.

― When I started this research, I mixed up 'collections' and 'archives'.

Kido For example, in our case, we have a collection of completed poster works and an archive of other materials. The challenge now is how to organise the materials other than the artworks. Until now, there has been no concept of an archive in the context of Japanese museums, so we probably don't know how to handle them. However, even under such circumstances, the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, which is scheduled to open in 2021(opening spring 2022), seems to be placing archives at the heart of its activities. The 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa has a full-time archivist. We hope that design archiving initiatives will expand in Japan as well.

― Thank you for your long hours today.

Enquiry:

DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion

https://www.dnpfcp.jp/foundation_e/archives/