Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

Photographer, Editor

Interview: 16 January 2024, 14:00-15:30.

13 Mar 2024, 13:30-15:00.

Location: Helico office

Interviewee: Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

Interviews: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Writing: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

Photographer, Editor

1939 Born in Tokyo

1961 Graduated from Tokyo College of Photography and joined the Japan Interior Design Institute. Engaged in editing and photographing for the monthly magazine “Interior”

1965 Became independent and worked as a freelance photographer

1973 Co-founded ZOOM with Yoshio Shiratori

1987 Established the photography office Helico

Awarded the Japan Interior Designers’ Association Prize

2018 Awarded the Mainichi Design Award Special Prize 2017

Description

Description

If the photographs taken by photographer Mitsumasa Fujitsuka were arranged in chronological order, it would surely be a comprehensive view of Japanese architecture and design. It can be said that Fujitsuka has confronted more architects and designers than any other photographer, getting to the essence of their work and documenting it in photographs. In other words, Fujitsuka's photographs are invaluable to the Japanese design archive.

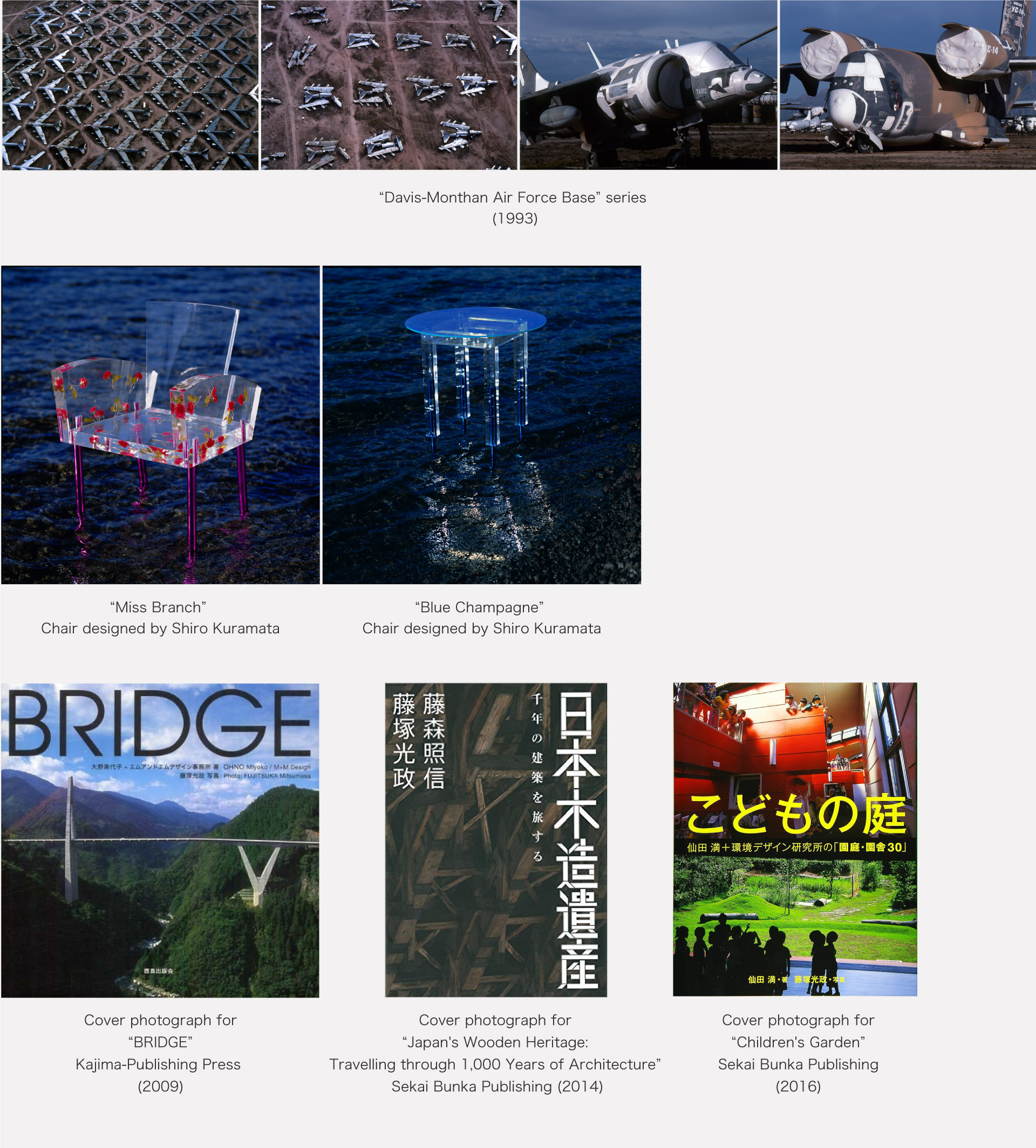

When actual objects such as architecture and tools are lost, photographs remain. Interior designer Shiro Kuramata was more aware of this than anyone else. It is Mitsumasa Fujitsuka who has photographed the largest number of Kuramata's works in chronological order.

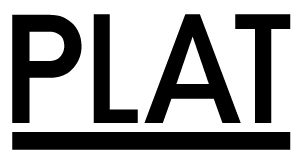

While these shoots were taking place, his unflagging curiosity and wild intuition led Fujitsuka to Japanese wooden architecture, sacred spaces around the world, children's spaces and aircraft storage site, whenever he could find a gap in his busy schedule. In addition, in 'What's going on? Technology Around Us', he has also written a playful book full of nature, science, crafts and fun experiments.

Whether it is architecture, design or nature, how widely and distantly he looks at the subject in front of him, perceives it, cuts it out and fixes it ......, is the unshakable strength of Fujitsuka's photography.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

“Sacred Space Engi (Shinsei Kuukan Engi)” Sumai no Library Publishing (1989)

Co-authorship: Kikou Mozuna, Bnding: Tadanori Yokoo.

“Architecture Riffle Series 10” TOTO Publishing (1992-1995)

“Davis-Monthan Air Force Base” series (1993)

“Design by unknown author " TOTO Publishing (1993) Co-authorship: Kikou Mozuna

“BRIDGE” Kajima-Publishing Press (2009) Co-authorship: Miyoko Ohno

“Japan's Wooden Heritage: Travelling through 1,000 Years of Architecture” Sekai Bunka Publishing (2014) Co-authorship: Terunobu Fujimori

“Children's Garden” Sekai Bunka Publishing (2016) Co-authorship: Mitsuru Senda

“The Legacy of Japanese Houses: Living on Masterpieces” Sekai Bunka Publishing (2019) Co-authorship: Yui Fushimi

Book

“What's going on? Technology Around Us” Shincho-sha (2002).

Interview

Interview

When taking any photograph, the basic question to ask myself is:

‘What was the creator thinking when he created this?‘

To the birth of the architectural photographer

ー What inspired you to become a photographer, Mr Fujitsuka?

Fujitsuka I experienced war as a child, born in 1939. When I was a child, I was fascinated by soldiers, especially fighter pilots. I loved aeroplanes so much that I had my own drawings of them pinned to the ceiling and looked at them even when I slept, so I wanted to be a soldier or pilot who flew them.

It was difficult for me to become a pilot because when I was in primary school I had tuberculous arthritis, which made my legs worse. In fact, my father was a camera enthusiast and often took family photos, so I naturally began to think about doing photography because the camera was around me. So, after graduating from high school, I enrolled at the Tokyo College of Photoraphy. I was encouraged by the fact that I met like-minded classmates and was stimulated by them, but in photography you have to think for yourself in the end, and the real work starts after graduation.

ー How did you end up joining the editorial department of ”Interior” magazine after leaving school?

Fujitsuka It was thanks to the master photographer Ken Domon. When I was thinking about what I was going to do after failing all the employment exams I took, my friend and pupil of Mr.Domon, Yoshimichi Ushio, introduced me to him. One day, Mr.Domon introduced me to a magazine called “Interior”, which was looking for an assistant, and I finally got a job. At the time, Domon's younger brother, Naomi Maki, was the head of the photography department of Interior. It was all thanks to Mr.Domon and my friend Ushio.

ー What kind of magazine was ”Interior” at the time?

Fujitsuka ”Interior” was launched as an advertising medium by a former member of the Sankei Shimbun newspaper's advertising department. At the time, Japan was in the throes of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and the advertising industry was very active, with a whole range of media being launched to carry advertisements. It put a lot of effort into the magazine's content and printing in order to sell advertising pages at a high price. The photography department consisted of four people, including myself, led by Mr.Maki.

My first important shot was of Honami Koetsu's national treasure, the 'Funabashi maki-e inkstone box'. It was a bold design, with a lead plate resembling a bridge pasted about a third of the volume in the centre of the gold maki-e inkstone box, and even today it has a great impact. When I actually hold it in my hand, I realise that the lightweight wooden inkstone box to which the lead plate is attached has a comfortable weight and fits easily in your hand. I only discovered this when I held it in my hand, and I thought that this kind of discovery was very important for photography.

ー What inspired you to photograph architecture and interiors?

Fujitsuka The Izumo Taisha Government House by Kiyonori Kikutake, which I photographed in 1963, was the first architecture I photographed. I liked the architecture, but it has already been demolished. This was one of Kikutake's early masterpieces, but I imagine it was not loved by the Izumo Taisha side. In the end, how much architecture is loved is the factor that allows it to exist for so long. If it is not maintained, any great architecture will not be connected to future generations.

ー From then onwards, as a photographer, what is your point of view?

Fujitsuka Photography is a way of conveying architecture in a two-dimensional graphic form, so I shoot with scene changes in mind, just like in a film. So it is important to capture architecture and space and develop them on paper.

ー When you say cinematic, do you mean the flow of the gaze or the experience of time and space?

Fujitsuka Photography is not a discourse or a theory, so I think it is important to take photographs that allow the reader to imagine the architecture as a whole, as if they are experiencing the architectural space at the moment they see it, or making their own discoveries through the photographs. That's why I was so conscious of the page layout in the photographs for “Interior”.

ー I have read that you have a side of an editor, and that's exactly what you are.

Fujitsuka At ”Interior”, I did everything from planning articles to photography and layout. I was supposed to be the editor-in-chief for the projects I was in charge of. My experience here has become my foundation.

The printing of it was done by first-class printers such as Mitsumura Printing and Tokyo Gravure, and the cover was designed by Yusaku Kamekura and Ikko Tanaka of Nippon Design Centre, with a luxurious large-format B4 variant, priced at an unbelievable 550 yen at the time. The articles covered not only domestic but also foreign architecture, and were written by well-known names such as architecture critics Noboru Kawazoe and Ryuichi Hamaguchi, and Sori Yanagi of Mingei.

ー By the way, you shoot both architecture and interiors - are there any differences between the two?

Fujitsuka No, there are no differences. To put a finer point on it, interiors are done on a millimetre-by-millimetre basis, while architecture is a bit more eagle-eyed, so there are differences. But the most important thing is the sensibirity of the architect or interior designer, and it is interesting to photograph things created by people with a clear design philosophy. It's fun to think about how they conceived and realised their ideas.

Meet Shiro Kuramata

ー Who did you think had the best sense of style among the people you met?

Fujitsuka Shiro Kuramata is the best. I first met him in 1963 when I was filming the San-ai Dream Centre (hereafter San-ai Building), which was built in Ginza. This was Shoji Hayashi's masterpiece and a symbol of Ginza, but it is currently being demolished due to its age. At the time, Mr. Kuramata was a staff member of San-ai's advertising department and designed the showcases and window displays for it. The showcases were a big topic of conversation, but this was the first project in which he used acrylic materials.

ー What was your first impression of Mr. Kuramata?

Fujitsuka Surprisingly, I didn't have a strong impression of him. He is a man of few words and unassuming personality. However, every word he uttered was unique, and I was impressed that he had a precise point of view on the subject.

ー When it comes to Mr.Kuramata, there are as many gems of language as there are works of art. They seem to hit the very essence.

Fujitsuka The phrase "I want to be free from gravity" succinctly describes what Mr. Kuramata was aiming for, and I think it contains his strong will. Especially in his later works, the names of his works such as "Miss Branch" and "Blue Champagne" convey the image of his thoughts. The names of Kuramata's works, as well as the words, often convey a sense of narrative and poetry.

ー What does Mr.Kuramata have to say about photography?

Fujitsuka No way. He didn't say anything. That's why we had to imagine what he was thinking when he made it. He is a special person for me. I think I'm probably the one who has taken the most photographs of his work from his early years to his later years.

ー There is currently an exhibition 'Shiro Kuramata's Design' (January 2024), and your photographs are once again attracting a lot of attention. Why did you photograph Kuramata's work, such as Miss Branch, by the water?

Fujitsuka I chose Lake Motosu several times as a shooting location. Some of Kuramata’s works from the 1970s, such as ' Glass Shelf' and 'Glass Chair', were shot in the sea. That filming was also made possible because the staff of Ishimaru and Mihoya Glass worked so hard. I would never be able to do that now.

ー And yet, in the water. ......

Fujitsuka The idea for that photograph was how to express Kuramata's concept of wanting to be free from gravity. When I wanted to get closer to his image, I thought of the water surface. I thought that the water's edge is the point of contact between air, water and earth among the four elements (fire, air, water and earth), and that it is a place that leads to the other world. It is also in line with Archimedes' principle.Two of the photographs, 'Miss Branch' and 'Blue Champagne', were taken for ”Katei Gaho”magagine, while the others were taken for the ‘World of Shiro Kuramata' exhibition at the Hara Museum of Contemporary Art in 1996. 'Miss Branch' gets a lot of coverage because it's such an innovative and shocking piece. Everyone was astonished by the use of artificial roses by Shiro Kuramata, a man who resonated with minimal art and disliked decoration.

Architects and their works confronted through the lens.

ー You started taking a lot of architectural photographs when you photographed the Government House of Izumo Taisha, didn't you?

Fujitsuka I became independent in 1965 and started doing work outside of “Interior”. Meanwhile, the publisher of ”Interior” changed, and in 1968 Kazuhiko Moriyama, who was Kuramata's classmate at Kuwasawa Design School, became editor-in-chief, and in 1970 the magazine's name was changed to ”Japan Interior”. Jukan Kawadoko and Kiyoshi Akimoto, who had studied architecture at university, joined the editorial department, and new projects were born one after another. For this reason, I started meeting young architects of the time in the mid-1970s and had more and more opportunities to take their architectural photographs.

ー This was a time when young architects, whom Fumihiko Maki called "wild warriors of the peaceful age", were presenting unique residential architecture.

Fujitsuka They all had their own ideas and worldviews, which I found amazing. But at the time, the clients who commissioned them to design their own houses were more impressive. Because they were even scolding the architects who hesitated, saying, "Are you sure you want to do this?

ー What were the masterpieces of the time for you?

Fujitsuka ’Anti-Segregation Apparatus’ by Kikuo Mozuna, ’Genan’ by Osamu Ishiyama, ’Yaizu Houses 2’ by Itsuko Hasegawa and ’Kataseyama House ’by Mitsuru Senda.

ー You seems to have hit it off particularly well with Ms. Mozuna. You co-authored " Sacred Space Engi " and" Design by unknown author " both with him, and you have said that you "became best friends on the day we met".

Fujitsuka That's right. These were the first of many trips I made to shrines and temples throughout Japan and to famous architectural sites around the world. I first met Mozuna when we were both in our mid-thirties. We went to see the 'Buried Cultural Heritage Research Centre', which became his career-making work. It was the day after I had visited the “Anti-residential apparatus“. The Anti-Dweller is a house that Mozuna built for his mother. It is a weird building, but when you actually go there, you realise that it is a triple cubic housing structure, a 'vessel' for a mother living in an extremely cold climate to live warmly in a multi-layered room.

“Anti-Residential Apparatus“ Designed by Kikou Mozuna

ー Osamu Ishiyama's 'Genan', presented in 1975, is also an extraordinary building, albeit on a small scale.

Fujitsuka ’Genan’, located in the mountains of Aichi Prefecture, is an architectural structure made of bent corrugated iron sheets, an industrial material, with an iron bridge and windows made of coloured glass inside, and is both a villa and a tea house. The tea ceremony room is a special space, but its unorthodox and other-dimensional space was too amazing.

ー How did you interact with the architects of your generation?

Fujitsuka We were equals. Photographers can only work with architects if they make architecture, but I was not afraid to dare them to take architectural photographs if I could. I thought it was not good to have a strange hierarchy between architects and photographers, and it is actually difficult to convey architectural space through photography.

ー Is it important to deepen mutual understanding in order to make good photographs?

Fujitsuka Not necessarily. It's more important to use my imagination and ask, "What was he thinking when he made this?" In particular, the architects of my generation that I met in the 1970s, such as Tadao Ando, Toyo Ito, Kijo Rokkaku and Kazuhiro Ishii, each had a completely different humanity, philosophy and architecture, and their individuality shone through.

Committed to Japanese wooden architecture.

ー How did you become interested in traditional and wooden architecture?

Fujitsuka In the early 1980s, Mr.Mozuna started a series of articles in a monthly magazine “Shitunai’. This later became a book called "Sacred Space Engi ". Since the roles were divided between Mozuna writing and me photographing, I had the opportunity to photograph shrines and temples all over Japan. This led me to realise that, unlike modern architecture born from Western logic, the indigenous natural structures of Japan, or rather Asia, are amazing, born from the vast land, diverse climates and peoples of the region. Is modern architecture, which builds strong structures out of concrete to compensate for nature, right? I realised that it is.

On the other hand, “Design by unknown author” is a book about tons of architecture and buildings around the world, but there is great power in things created by religions, kings and overwhelming power.

ー At the time, you were strongly attracted to this type of architecture as well as contemporary architecture.

Fujitsuka Of course I love contemporary architecture. I was deeply moved when I went to England on business and saw that the iron bridges built during the Industrial Revolution are still in use after more than 200 years, but on the other hand, modern architecture in Japan only has a lifespan of about 100 years at best. But there are also many architectural structures around Japan that have been alive for more than a thousand years. Through the filming of ”Sacred Space Engi”, I was once again fascinated by wooden architecture.

ー In that sense, the bestselling “Japanese Wooden Heritage” is a sequel to“ Sacred Space Engi”.

Fujitsuka The theme of Japanese wooden architecture is consistent. Mr.Mozuna passed away, but in 2012, “Katei Gaho”magagine decided to serialise it as a series called 'Japanese Wooden Heritage'.

ー The book was co-authored with Terunobu Fujimori, but you were the one who decided on the locations for the filming, was that correct?

Fujitsuka Yes. The most important thing was the passion of "I wanted to shoot!", so I decided where to shoot. For the text, I asked Mr. Fujimori to give a historical perspective and Mikio Koshihara, a professor at the University of Tokyo, to explain the structure of wooden architecture. I guess you could say that Mr. Fujimori's writing fits me, I can relate to it. Maybe we communicate on a sensory, unconscious level rather than through discourse. I think he really enjoys architecture.

ー For you, do you take the same stance in taking photographs of both contemporary architecture and wooden architecture?

Fujitsuka Yes, because I am the one taking the photographs. Whether it is contemporary or traditional wooden architecture, the basic question is: "What was the builder thinking when he built this?" This question is the motivation for my work.

When I actually go to a shrine, you are face-to-face with the gods, so I feel a sense of awe. There are wooden church buildings in Northern and Eastern Europe, but their appearance is completely different from that of Japanese shrines and temples. I think this is due to differences in climate and vegetation. Japan has a variety of climates, from Hokkaido to Okinawa, and is truly a vast forest. That is why the Japanese people have nurtured forests for timber in this rich natural environment, and have not neglected the repair and maintenance of buildings, paying attention to, maintaining and passing them on over generations, just as if they were caring for their own bodies. In short, buildings were positioned as part of the natural cycle system. More specifically, the Japanese recognised and interacted with trees, plants and flowers as intelligent beings. This sense of awe towards nature and ecology is at the root of Japanese wooden architecture.

ー That's really true. At the end of the book, you states that "existing wooden architecture is not a thing of the antiquated past, but a continuous living contemporary architecture, and at the same time, a 'future architecture' to be handed down to future generations".

Fujitsuka's photo archive

ー In a career spanning more than 60 years as a photographer, you has photographed many architects' and designers' works, as well as valuable buildings in Japan and abroad. They are also valuable design archives of Japan. What are your thoughts on this?

Fujitsuka I don't really feel that my photographs are an archive of architecture or design. I feel that what's done is done, and I approach my photography with the same mindset as I do now and in the past. First of all, I'm still alive and I plan to shoot until I'm 100 years old, so I never think about it seriously.

ー So, changing the question, how do you currently storage the vast amount of photographs you have taken?

Fujitsuka Film is stored in the office under temperature control and sorted by artist. I have a list in my head of photos that need to be digitised, but I haven't been able to do it. However, since about two and a half years ago, staff member Hisamoto Sato has been gradually organising old photos and magazines. The Kodachrome I used in the 1980s is very durable, so that helps. I recently printed an enlarged 1.5 x 1 metre print of an aerial photo of Gunkanjima taken with a 35 mm Kodachrome, and it was fine and accurate. For a long time, Kodachrome was recognised as the official film of magagine of “National Geographic”.

ー So you are also a fan of small cameras, aren't you?

Fujitsuka I generally use a small SLR camera. It's lightweight and allows me to capture the moment. Especially when it comes to architectural photography, where I want to capture a particular period or time, I use a small camera that I can press the shutter at the exact moment when I feel "right!

ー However, as time goes on, photographs and video images are becoming digitalised and can be processed as much as possible after they are taken. What do you think of these changes?

Fujitsuka I also shoot digitally, and as long as people are taking pictures, there is nothing to worry about. But if I'm not good at it, a photographer's job might turn out to be like an illustrator's. But that might not be an option. I don't do it, that's all. For me, filming is an act similar to hunting.

ー Do you hunt? It's the first time I've heard of it.

Fujitsuka I quit a few years ago, but I've been doing it for over 40 years. In both hunting and photography, I can develop intuition, or a sense of intuition, by aiming for a moment that will never happen again. Yes, Mr.Kuramata also used to shoot when he was young.

ー Really? I was surprised. By the way, Kishin Shinoyama passed away recently, what generally happens to photographers' archives? Are they donated to museums?

Fujitsuka I haven't heard of anything like that. I think someone as great as Mr. Shinoyama would organise and store his work. Ken Domon has the Domon Ken Memorial Museum in Yamagata Prefecture, where he was born, with more than 130,000 items in its collection. I think it would be a good idea for the Museum of Modern Art and other museums to collect socially and historically valuable photographs, or to convert them into digital data. The reality is that photographs as works of art can be housed, but there is nowhere else for them to go.

ー Lastly, you mentioned earlier that you will continue to take photographs until you are 100 years old.

Fujitsuka What I would like to try one day is to publish my own photo book. Then I want to photograph Italian stone architecture. My first trip to Europe was in 1969, when I was shooting a Scandinavia feature for Japan Interior. I was very impressed by the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II in Milan. I wish I could do it again. I would also like to photograph the Pantheon in Rome.

ー I would love to see Mr. Fujitsuka's Pantheon, there is still time until he is 100 years old. I look forward to seeing what kind of photographs you will take in the future. Thank you very much for today.