Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Makio Hasuike

Designer, Creative Director

Date: 25 October 2022, 17:00~18:30

Location: Online

Interviewee: Makio Hasuike

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki and Mirei Takahashi

Autor: Mirei Takahashi

PROFILE

Profile

Makio Hasuike

Designer, Creative Director

1938 Born in Tokyo

1962 After graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts, worked for Seiko as a designer

1963 Moved to Italy and worked in Rodolfo Bonetto's office

1968 Founded Makio Hasuike Design in Milan

1982 Founded MH WAY, a brand of bags and accessories

2016 Awarded the Compasso d'Oro career prize, the pinnacle of design in Italy

2022 Honorary Member of ADI, Italian Desgin Association

Founding member of the Master Program Strategic Design at Politecnico di Milano. Lecturer at the Faculty of Industrial Design, Politecnico di Milano, Domus Academy, and Raffels Institute.

Description

Description

Makio Hasuike is one of the main pioneers among Japanese designers working abroad. He has been living for 60 years in Milan, Italy, where he has been working through his own design studio.

During his years of study at Tokyo University of the Arts, Hasuike attracted much attention for his brilliant achievements by winning in 1960 the MAINICHI design competition. At that time his dream was to become part of the leading international designer scenario and wanted to get experience in and out of Japan. In 1962, he started working for Seiko, with a promise to stay there for only one year. His first professional job with the company was to design 20 different watches to be officially used for the Tokyo Olympics games in 1964. In 1963 Hasuike left Japan and, during his first visit to Italy, was immediately hired at Rodolfo Bonetto's design studio. It was more than just good luck; it was a proving of the appreciation of his design skills.

Makio Hasuike founded his own studio in Milan in 1968. Thanks to his own design projects he attracted the attention of La Rinascente, the most important department store in Milan. La Rinascente was looking for designer to be envolved in new projects and Hasuike was with Gio Ponti and other designers in the selected ones. Makio Hasuike Design Studio is considered one of the first industrial design studios in Italy among foreign designers. The studio, since the foundation and up to nowadays, operates in a wide range of design fields, from housewares to large yachts, working directly with company entrepeneurs to realize their "dreams."

Hasuike further became known for his original brand "MH WAY." In 1982, he made a revolutionary bag that became popular and had a great impact on the European fashion scene.

In 2016 Hasuike receives the Compasso D’Oro lifetime achievment, the most prestigious design award in Italy. To this day he continues his activity.

We interviewed Mr. Hasuike about the need to organize his past works and about the current state of general design archives in Italy.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

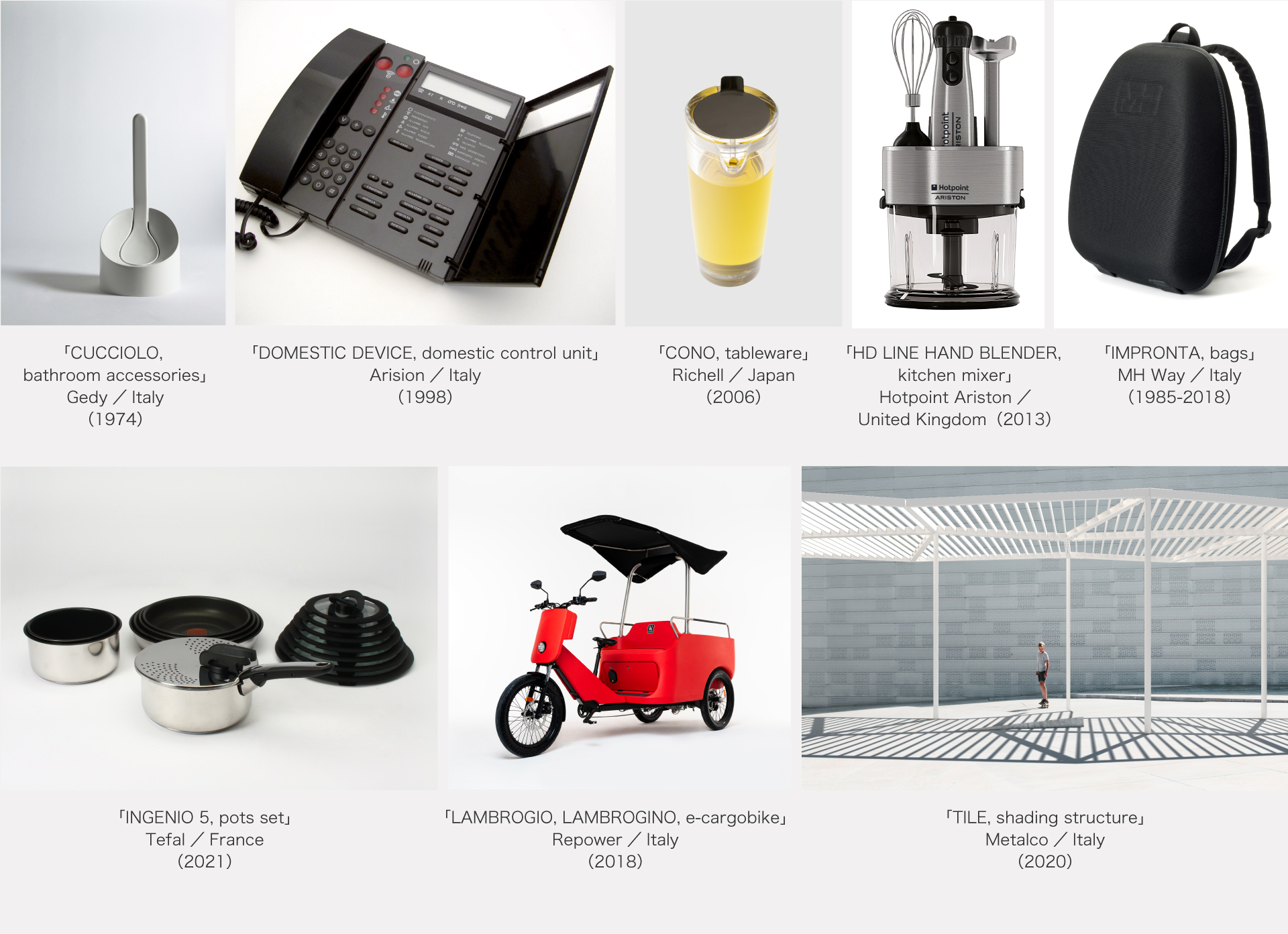

「SAKURA, tea set」Ceramica Franco Pozzi/Italy(1967)

「CUCCIOLO, bathroom accessories」Gedy/Italy(1974)

「CANADOS 65, yacht」Canados/Italy(1981)

「PIUMA, briefcases」MH Way/Italy(1983)

「ZOOM, drawing holder」MH Way/Italy(1986)

「BACIONE, packaging」Perugina/Italy(1988)

「AUTOTUNE, car radio」Panasonic/Japan(1990)

「OPERA, thermal carafe」 Alfi Zitzmann/Germany(1991)

「DOMESTIC DEVICE, domestic control unit」Arision/Italy(1998)

「CONO, tableware」Richell/Japan(2006)

「HM LED, table lighting」Yamagiwa/Japan(2007)

「INGENIO 5, pots set」Tefal/France(2012)

「HD LINE HAND BLENDER, kitchen mixer」Hotpoint Ariston/United Kingdom(2013)

「IMPRONTA, bags」MH Way/Italy(1985-2018)

「LAMBROGIO, LAMBROGINO, e-cargobike」Repower/Italy(2018)

「TILE, shading structure」Metalco/Italy(2020)

「KSD, engine」Kholer Engines/United States(2021)

Interview

Interview

60 years of life as a designer in Italy

On the meaning of looking back at past work while still in active service

The award was triggered by his student days

ー First of all, please tell us about your life as a designer, Mr. Hasuike. You were classmates with Motoko Ishii at Tokyo University of the Arts, and both of you are active designers, but what made you decide to go to Milan in the first place?

Hasuike I was an enthusiastic design student at Tokyo University of the Arts. One of our teachers at that time was Professor Iwataro Koike, who launched the GK Design Group and attracted a lot of attentions from the public. I think we were a generation that was very stimulated by the times when we were students. At the university there was a rule that we were not allowed to participate in open competitions or work into design field until the third year course. I hoped to become a designer as soon as possible, so I immediately collaborated with elder students to gain experience in design competitions. During my third year of university, I decided to enter the Mainichi Design Competition, where some of the most famous designers of the time presented their works. Big companies like Sony and Honda were also involved. Eventually I won the first prize through the design of a Yashica 8mm zoom camera. It was a great opportunity for me. Because of the prize, I was asked by many companies for interviews and appeared in different magazines, thus receiving many job offers. I decided to apply for Seiko because it was the company that offered the most of freedom and a good salary. However, I knew that the visibility given by the first prize would have disappeared soon. I had to keep working and going abroad would have been a good way to gain experience. When I honestly confided my feelings about this before I started working at Seiko, the manager said that if that was the case I would absolutely have to leave. Nevertheless, I decided to stay with the company because I needed to experience design work. We agreed for one year. I was lucky because in 1964 the Tokyo Olympics were held and at Seiko I was assigned to work for the design of the Olympics watches. It was there that I first learned that watches are different for each sport. I designed 20 kinds of watches for different sports. For example, for boxing, watches that would be invisible to the players but visible to judges and spectators.

At the end of one year working at Seiko, I worked at Yamagiwa and other companies to gain financial autonomy and work experience. After establishing my financial conditions, in October 1963, I left Japan. Next year will mark the 60th year of my life in Italy.

The reasons for independence in Italy instead of Japan

ー Did you think from the beginning about starting your own business in Italy?

Hasuike Actually, I left without knowing much about Italy. My plan was to leave Japan in the fall of 1963, travel from Europe to United States and return home after two or three years. When I arrived in Rome, I felt that there was still no design atmosphere there, and my friend from Tokyo University of the Arts, architect Kanji Hayashi, who was working in Rome, advised me to go to Milan. There I met Ms. Kazuko Sato, who later became a design journalist. She was there on a government-funded scholarship and was working in a design studio, so I called her and she told me to meet her at the studio. The reason was that Ms. Sato had decided to go back to Japan and had asked me if I would join the office instead. That was Rodolfo Bonetto Studio. I visited them not knowing what to expect. Mr. Bonetto asked me to show him my design portfolio, so I showed him what I had and he asked me what I wanted to do. I told him that I had seen Italian design in magazines like "domus" and that there was a designer I was strangely attracted to, and he asked me who he was. I spontaneously said "Sottsass," and of course he was annoyed. But when I told him I would like to work at his office, if I could, he immediately checked to see if there was room in another staff's guesthouse that was just around the corner, and straight away I moved there. The next morning I started working in Bonetto's office.

There were some differences between my feeling of design and Bonnetto's, but four years have passed. The reason is that product design, in particular, takes a considerable amount of time from the moment it is initiated to the results it achieves. However, it was a good experience for me to get to know the entrepeneurs of Italian companies during my stay at Studio Bonetto and I had a chance to participate in discussions and proposals along all the design process. There were only four people in his studio, including Bonetto, and at that time he was working on Olivetti and many other types of design work. It was a moment when company entrepeneurs would personally meet the designers and tell them their thinking about the product, and the role of designers was to give shape to their dreams, rather than just trying to sell the product. I was very impressed by that.

I already knew that there was a lot of beautiful and exciting design in Italy, but I realized that was not only because of the designers, but also because of the ability of entrepeneurs. There was a good ground in Itlay for design to flourish.

ー Why did you start working in Milan even though you planned to return to Japan after a few years, and why did you decide to go out on your own?

Hasuike I had been in Bonetto Studio for just four years, but some Japanese producers were waiting for me because I had left my country with the promise to return after a couple of years. For example, Mr. Hyogo Konagaya of Yamagiwa Electric (now YAMAGIWA) at that time trusted me a lot and listened to my advices and opinions. Yamagiwa was involved in the Japanese Expo with exclusive rights to sell European brands in Japan.At the same time, the company, under the advice of Takamichi Ito who was in the same year of university as me, was also organizing the international design competition.

When I return to Japan I was than asked to work for them. However, during my August summer vacation in hot Japan, I strongly felt one thing: I had been in Milan for four years doing a lot of work, around the same time I was designing a new television set, and when I saw the Japanese space, I realized that I was doing something completely different. I realized that at that time there was quite a difference between Japan and Italy in terms of architecture, living environment or the relationship between people, space and objects. I understood that what I considered good design in Milan would not have been good design in Japan. This also made me realize how difficult it would have been to start again working as a designer in Japan. I did not want to loose my previous experience. The passion I felt in Milan for design, the passion the company entrepeneurs had, the Italian desire for aesthetically superior products. So I went back to Milan, realizing that in Italy I could continue what I was doing. However, I could not stay at Studio Bonetto as it was, so I submitted my resignation, and he offered me to stay for another six months. I left the following spring to start working at home in 1968.

Lucky encounters and personal connections

ー Imagine that it was not easy to settle in Milan as a foreigner. Were you immediately successful in your work?

Hasuike There was an unexpected episode that marked my career. Before temporarily returning to Japan, I had made a mock-up of a tea set design with the intention of entering a design competition in England. However, before sending the tea set mock-up, I red again the brief which surprisingly was indicating "it must be silverware." Since I had made it in ceramic, I couldn't submit it and left it on my desk at home. Back from Japan, one of my friends who had met at night in my small apartment found my project and asked, "What is this?" After explaining the competition, he said, "It's interesting and I want to show it to my superior." He was the head of Rinascente, a historic department store in Milan. I showed them my tea set as it was and they said it was a good design. They wanted Franco Pozzi, a subcontractor of Rinascente, to produce it. The manufactory was run by two brothers, one of whom was the designer, Ambrogio Pozzi, who from that time began to produce Gio Ponti's ceramics as well. After it was made, my design won an award for Italian design and an exhibition was held displaying the design of three people: Gio Ponti, Ambrogio Pozzi and myself.

After ending my collaboration with Bonetto Studio, because of my reputation, I was immediately contacted by two companies. One was Ariston, a manufacturer of home appliances in the heart of Italy, which was not very famous at the time. The other was Gedy, a manufacturer of bathroom accessories. I immediately started working and realized that life is about people and relationships. Vittorio Merloni, president of Ariston, was a very charismatic figure. When I started working for him he was still young, about 35, but he was already a central figure in the company as a second generation alongside his father. Our professional journey started then and lasted until 2014, more then 46 years. My working position toward him has always been as a freelance designer and I think that this position was the only one to establish such a long working relationship.

I designed not only home appliances, but also his yacht. I also remember when I designed a large cruiser, about 30 meters long, and when I went to Sardinia to see it. My name "Makio Secondo" was clearly visible on the back of the yacht. I worked with him often, meeting and talking with him, even receiving letters of appreciation from him. "Makio is not just a designer, he is a man of strategy. He has a vision, and he is a man who realizes it." He was a refined businessman who later became president of the Italian Business Federation. He died and the brand was absorbed by another company, but we worked together from a young age for 46 years as we grew into an international company. He was proud of the gained success and appreciated my work because I respected and designed his vision.

ー Besides these good relationships with the owners, what else do you feel is unique about Italian design?

Hasuike Design is not only about creating a form, but also about why it should be made in that way. Together with Ezio Manzini, a lecturer at the Milano Pilitecnico, I founded a course to teach "Strategic Design" at the end of the 1990s. The course was created because it is difficult to connect design to a vision, unless it is strategic, and it is also difficult to deal with major environmental issues. In my case, my feelings have not changed since I was in college, and since then, I interpret design as an important task to improve people's lives. I use the great power of industry, as I remember the achievements of the Bauhaus and others. When I first came to Italy, I was a little surprised to find that many of the people interested in architecture and design were nobles, or rather wealthy, high-class people who were used to a luxurious lifestyle. Their work mainly involved interior design for the homes of wealthy people. Style and elegance were important to them. The Italian word for beauty or elegance is "beautiful," which also includes the nuance of "interesting." Since I believe there are many elements in design besides beauty, I have always felt that Italians have also some other sides of interest: a wonderful side as well as a fun side. However, after some time, I realized that they were right. Because design must spring from a dream. This is more important than evaluating if a design solution is luxurious or not. To what extent can designers shape this dream as something that people can use? It is understandable that one might be tempted to think that it is enough to simply have universality or superior functionality, or that it would be smarter not to design, but Italian design is about creating something more dreamlike and satisfying than that. Beyond that, it is difficult to design without a strategy in terms of how to carry it out. The reason for this is that companies tend to forget their dreams when they are in a difficult situation, where everyone is competing, and if they are not profitable, they will die. That is why designers are important. Being a designer is a hard work, but I guess I can say I enjoy it because without this work I would have no life. But, well, I got this far after putting a lot of energy and in some cases even struggling.

ー It seems like you have succeeded in Milan very naturally, but have you experienced any particular difficulties?

Hasuike I'm sure many things happened, but I don't remember them all at once because I tend to forget unpleasant things.

I met the designer Giorgetto Giugiaro just 10 days ago at a conference held at the University of Milan on the subject of Japan and Italy, and he reminded me of something that happened a long time ago. I had done various projects for Ariston. The company after about 20 years became international and gradually absorbed several brands. As for me, I had to design for three brands by myself, thinking I could do everything, but nevertheless the president invited Giugiaro. He said, "I want the most famous and talented designer in the world." He is, of course, known to everyone as a top designer in Italy, where car enthusiasts are paying attention. He even held an inauguration party in Capri. At that time, everyone, even the people in the company I had worked with up to that point, started to really like him, and I thought, "Who is this?" The competitive mentality, or rather agony, lasted for about a year, although I had never been that kind of person to work with a competitive mentality. However, when my work was successful and I regained enough of my dominance, I formed a good relationship with Giugiaro.

Original brand "MH WAY"

ー Mr. Hasuike is well known for his bag brand "MH WAY". What was the designer's idea behind launching the brand and developing it globally?

Hasuike About 10 years after I started working for Gedy, a manufacturer of bath toiletries. Once the owner, with whom I formed a friendly relationship, said to me, "Thanks to you, we are No. 1 in bathroom accessories industry." I asked him how much of that success was due to design. He thought about it for a moment and said, "20 percent." What? I thoguht it was 80%. That comment from Gedy’s owner was what pushed me, and that's why I wondered what it would be like if I had done it myself by creating a design company.

And there was also another personal reason. I got married in Milan and divorced 10 years after our two children were born. There were many reasons for that, but the woman I met later, my current wife, told me she wanted to try her hand at production. I thought what I could do, and because I remembered the Gedy story I mentioned earlier, I put together my feelings, my strategy and my vision. At that time, bags were more common than backpacks, and most were heavy work bags with aluminum frames. I thought I would like to have a lighter bag, and maybe because I am Japanese, I tried to make one with an origami-like structure, using lightweight plastic. My intention was to put my design ideas in this lightweight and thin bag and give it away once I finished the design work. But I wondered how other people could use this bag. I designed eight models of both the drawing case and the handbag. The technology consisted of folding the plastic and fasten it with a button. Since this is a very simple process and easily replicated by others, to avoid imitations on the market, we used original molds made by us to make the handles and fasteners. In the beginning, optimistically, I rented a booth and exhibited at a trade show in Milan for stationery and other products, and I was surprised to hear that on the first day people were arriving from all over the world and orders were coming in from Australia, Malaysia, the United States, and more than a dozen other European countries. This became a full-fledged business. I created the brand name MH from my initials and branded it.

In Milan I noticed professionals, especially architects, graphic designers and journalists, who appreciated MH WAY products and used them right away. In the blink of an eye, the number of people who had one bag increased to the point that if you walked down the street, you were sure to meet someone. Subsequently, I thought about designing something new, something different. But what I didn't realize was that as a brand, once you got into the stationery world, you would be tied to that world. People who were selling and doing business with me started asking me for something in line with that market because they were in that specific market. I thought, "Well, then I have no choice but to make the next stationery product." It's as if the first product established the fututre development. However, with the spread of personal computers, the need to draw on paper diminished. About a year after the initial bag was launched, a dozen Italian manufacturers began producing similar products, and those bags, for example, were rinstead used by children for carrying drawings. I realized that running a business is not only about having a good product, but also about relationships, accounting, distribution, taxes, problems with subcontractors, and product management--a number of difficult issues. In this context, I can now realize that what was considered "about 20 percent design" was a generous assessment. Such experiences have also deepened my understanding of the companies business.

ー There are not many projects in Japan, is there any reason for this?

Hasuike Long time ago, a magazine article appeared in Japan that said "Hasuike moved to Italy because he hates Japan and will never work in Japan" creating a misunderstanding since this is not true. For more than ten years now, I have been working on new designs for the Japanese design company Richell, which is headed by my cousin, and there was even a year when I was commissioned by design producer Mr. Toshiki Kiriyama to do work for Canon.

Design Archives in Italy

ー From here, we would like to know about the Italian design archives. What specific efforts are being made by each design institution?

Hasuike In Italy, design is particularly concentrated in Milan. There are currently two institutions in this city that house the achievements of various designers.

One is the Triennale di Milano (Triennale Design Museum). Rather than looking at each designer's career from a panoramic viewpoint, the museum selects works by period and preserves projects considered important, with a view to making them part of the history of Italian design. The other is the Italian Industrial Design Association (ADI = Associazione per il Disegno Industriale). It is an organization that administers the Compasso d'Oro, the most prestigious design award in Italy, similar to the Japan Institute of Design Promotion in Japan. With the support of the City of Milan, it has expanded as a design museum, managing works awarded the Compasso d'Oro and organizing temporary exhibitions. Recently, the museum has begun using the association's old building to keep records of past designers and to archive the works of designers who have passed away in recent years. The issue of design archiving is also becoming a growing problem in Milan, and although there is no clear evidence yet, they are in the process of starting to work on it. The Triennale has formed a sort of selection committee, with about 10 people working each time to select the projects to be held. ADI, on the other hand, is working on a systematic organization project for individual designers, and is trying to put together a museum for the Compasso d'Oro Award, which has been going on since the 1950s, and for the important projects that are kept in the museum. ADI has been working on this since the 1950s. The Triennale also has a similar collection from 1950 to the present and includes some of my projects.

Alternatively, there are several situations where individual designers, such as Achille Castiglioni and Vico Magistretti, for example, have established foundations represented by their surviving family members for archiving.

ー There are several important furniture manufacturers in Italy, such as B&B, Cassina, and Kartell, and is there not a lot of activity in such company-oriented design museums?

Hasuike Kartell has a museum outside Milan, but in many cases it does not. On the other hand, there are definitely private collectors. Just last night, at the opening of the exhibition, I met a private collector who told me he had a collection a hundred times larger and that only a fraction of his collection was on loan for the exhibition. But to hear him tell it, it is a bit different from an archive of historical importance, in that it is a collection of his personal taste in Italian design from the 1960s onward.

Storage of works in the office and archiving for the future

ー Your design studio is involved in a wide range of projects, from cosmetics to furniture and interior design. How do you keep such work materials, sketches, drawings, models, etc.?

Hasuike As you know, I am getting very old, and although I am still working, we have more and more discussions about the future. If there are 1,000 past projects, even 1/10, or 100 pieces, is too many, but I would like to keep even 30 or so. You can digitize them, but I want to keep them as objects, in other words, the prototypes and the products themselves. In fact, in the last year or so, we have had people from the University of Milan join us in discussing which method was best. The content is very broad, so we finally got started. In my case, I was involved in a wide range of design activities, not limited to one section, so obviously it was impossible to collect large real objects such as interiors, but they remained in the form of drawings, sketches and renderings, with 1990 probably being the dividing line. Before that time, most designs were done on paper and drawings were done by hand, but around 1990 computers were used. Digital data must still exist somewhere, but another problem is that it is easier to find paper than digital data. It is rather easy to find paper and objects prior to the 1990s. There is some confusion, but I am sure they are somewhere.

ー Is there some sort of storage in your studio?

Hasuike My studio is a large building, about 1000 square meters. I am using about half of it for storage. Our work also varies considerably from time to time, so at the time I set up this studio, I had a staff of about 20, but I was thinking of an environment where a maximum of 50 people could work at a leisurely pace. With that image in mind, I decided on this location for my studio, and since my present staff is only a few people, the space is very generous, and it serves as a storage area.

ー Are there any staff members who will carry on Mr. Hasuike's intentions?

Hasuike While I am still in my active years, I would like to talk about each of my jobs, why I came up with this kind of design, and what I have been trying to achieve. Because a design is not complete just by giving it a form. I would like to talk about my own work, because a design is not complete just by giving it a form. With this in mind, my daughter, Naomi, is now playing an increasingly important role in my studio. When I first started working in Milan, I worked for four years in Bonetto Studio. So, I had a pretty good idea what to do, but I think I was the first foreigner to set up my own studio in Milan at that time. It was like stepping into the Milan design industry, but in 2016 I won the most prestigious award of my career, the Compasso d'Oro lifetime achievement, and I was deeply moved by the fact that I had already reached such an age. I continued to work for a long time after that and received another Compasso d'Oro award in 2022. I hope to continue designing as long as I still have energy.

ー We look forward to presenting new designs in the near future. Thank you very much for your time today.

Enquiry:

MAKIO HASUIKE & CO

https://makiohasuike.com