Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

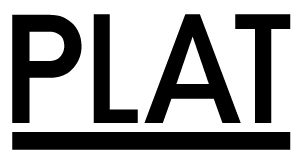

Yoshio Hayakawa

Graphic designer

Interview01: 6 March 2024, 15:00-16:30

Interview02: 3 April 2024, 11:00-12:30.

PROFILE

Profile

Yoshio Hayakawa

Graphic designer

1917 Born in Osaka

1936 Graduated from Osaka Prefectural Kogei High School, Crafts-design department

1937 Joins Mitsukoshi Department Store, assigned to the decoration department of the Osaka branch

1938 Military service

1943 Demobilised from China and reinstated at Mitsukoshi Department Store

1944 Moved to Osaka City Hall, Cultural Department

1945 Re-called up and reinstated at Osaka City Hall after World WarⅡ

1948 Joins the Advertising Department of Kintetsu Department Store

1952 Resigned from Kintetsu Department Store and became a freelance designer

1954 Establishes the Yoshio Hayakawa Design Office

Awarded Osaka Culture Prize

1955 Awarded the first Mainichi Industrial Design Award

1961 Opened Tokyo office in Ginza

1964 Appointed professor at Naniwa University of Arts (now Osaka University of Arts)

1971 Osaka office closed

1982 Awarded Medal with Purple Ribbon

1984 Awarded the 5th Yamana Prize

1988 Awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon

1998 Moved office to his home in Kamakura

2009 Passed away

Description

Description

Yoshio Hayakawa was a maestro of post-war graphic design. In the 1950s, after the end of the war, Japan finally emerged from the post-war recession and confusion triggered by the Korean War Special Demands, and the industrial economic recovery began in earnest. In the field of industrial design, manufacturers established in-house design departments one after another, and in the world of visual design, the Japan Advertising Artist Club was established in 1951 and became socially recognised. In the graphic design world, in addition to those who had been active in the field before the war, a new generation of the war generation emerged and a new form of expression was sought. At the heart of this were the two masters who are said to have been described by the critic Masaru Katsumi as "Yusaku Kamekura in the East and Yoshio Hayakawa in the West".

Kamekura was born in 1915 and Hayakawa in 1917, two years apart in age, but they were almost contemporaries. Kamekura was one of the design members of the propaganda magazine "NIPPON", launched by Yonosuke Natori and others during the war, and after the war he continued to work on national projects and CI designs for major companies, taking the high road in the design world. Hayakawa, on the other hand, served two tours of duty during the war, the first of which was a five-year stint in China, during which time he had to take a break from design work. After the war, he emerged as a graphic designer based in Osaka and later moved to Tokyo, where he developed his own activities that were distinct from national projects.

In terms of style, the two artists were also contrasting, and were described as "Kamekura for composition, Hayakawa for colour", and it is clear from their writings and conversations that they were both aware and conscious of this. In contrast to Kamekura's straightforward design, Hayakawa's characteristic beautiful colours and delicate, poetic expressions have multilayered nuances that entrust the message to the viewer and the recipient without being direct. Kamekura, Ikko Tanaka and their contemporaries objectively perceived design and promoted modernisation, Hayakawa dared to distance himself from this vortex and subjectively explored his own aesthetic sense based on design methods. It is precisely because today's demand for clarity, simplicity and transparency is so high that the complexity of Hayakawa's design, which is not straightforward, and which he describes as being between 'fiction and reality', is seen as fresh and new.

This time, we spoke to Tomio Sugaya, the director of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, which holds the Hayakawa collection, the director of the museum and the chairman of TCD, Takao Yamada, who worked in the Hayakawa office for 10 years, were interviewed about the Hayakawa collection and archive, his personality and his work.

Masterpiece

Representative works

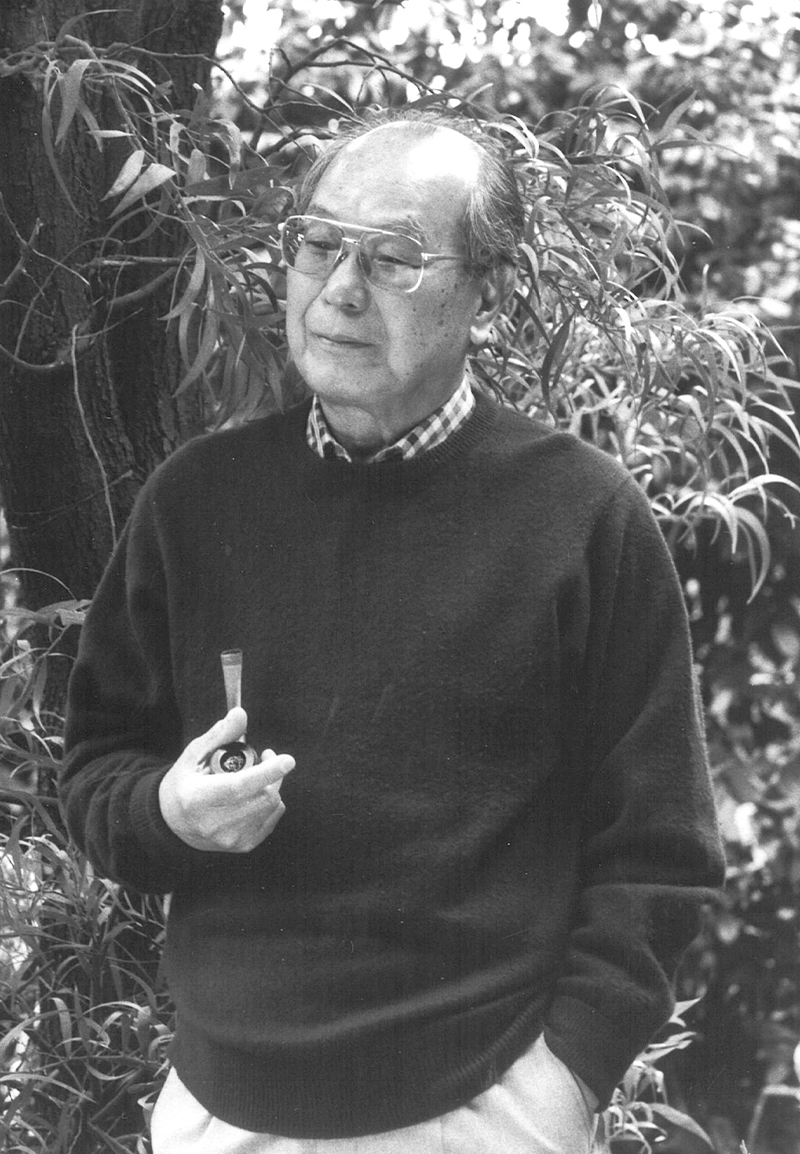

Poster 'Kalon Institute of Western Dressmaking' Kalon Institute of Western Dressmaking (1951-)

Poster 'The 7th Autumn Shusaikai' Kintetsu Department Store (1951-)

Magazine cover "Design" Bijutsu Shuppan-sha (1963)

Logo 'Kansai Television' Kansai Television (1963)

Monument, now Toyobo Tsuruga No. 2 Plant (1964)

Poster 'The 5th Tokyo International Print Biennale' (1966)

Magazine cover "Bungaku-kai" Bungeishunju (1971-1972)

Book cover ” Anthology Shigeru Izumi ” Kodansha (1978)

Tapestry, Tsukamoto Memorial Hall, Osaka University of Arts (1981)

Poster 'Seibu no Kimono', Seibu Department Store (1982)

Ceramic wall, Acty Osaka (1983)

Poster 'The First Tokyo International Film Festival' Tokyo International Film Festival Executive Committee (1984)

Poster 'Understanding Culture' Ina Seito (1984)

Book binding " Works of painting, Shigeru Izumis" Kodansha (1989)

Mural, Nankai South Tower Hotel lobby (1990)

Poster "Zero" Morisawa (1991)

Poster '50 Years of Japanese Illustration' Ginza Graphic Gallery (1995)

Magazine cover "Nikkei Design "Nikkei BP (1995)

Artwork

Artwork 'Shapes' series (1968-)

Artwork 'Faces' series (1968-)

Books

"The World of Yoshio Hayakawa", Takeo (1983)

"The World of Yoshio Hayakawa: His Emotions and Shapes" Kodansha (1985)

"The Sense of Idleness" Youbisha (1986)

ggg books 4 "Yoshio Hayakawa" Ginza Graphic Gallery (1993)

"Yoshio Hayakawa's Work and Surroundings", Rikuyosha (1999)

Naniwa Juku Sosho, Vol. 73, " Between Imaginary and Reality", Brain Centre (2000)

Interview 1

Interview 01: Tomio Sugaya

Interview: 6 March 2024, 15:00-16:30

Place of interview: Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

Interviewee: Tomio Sugaya (Director, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka)

Interviews: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Auther: Yasuko Seki

In Hayakawa's mind, there was a clear line

between design he wanted to leave behind for future generationsand

and those he did not want to leave.

Meeting Yoshio Hayakawa

ー We would now like to talk to you about Hayakawa's work and his archive as the director of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, which houses the Yoshio Hayakawa Collection. First, how did you two meet?

Sugaya I have known Mr Hayakawa since the last years of his life, more than ten years before his death. I think we first met in the mid-1990s. After moving his base to Tokyo in 1961, He continued to work in Osaka, producing tapestries and objects in addition to graphic design.

It should be noted that he energetically held solo exhibitions at places such as Imahashi Gallery and Ban Gallery, run by Mitsue Matsubara, where he presented his life's work, the Shape and Face series. It was also a place of exchange between people related to him and designers in Osaka, and I think it was on such occasions that I met him.

ー Mr Hayakawa passed away in 2009 at the age of 92, and ten years before that, he published a book entitled “Between Imaginary and Reality ”. This was a compilation of talks he gave at a course called 'Naniwa Juku', and the afterword to this book was compiled by you, wasn't it?

Sugaya Naniwa Juku is based on the tradition of the academies that existed in Osaka during the Edo period, and is a series of talks by people active in Osaka, which were later published in book form as Naniwa Juku Sosho . “Between Imaginary and Reality ” is one of the books in the series.

ー Did you two developed a relationship through these meetings?

Sugaya Yes, that's right. I was approached by him when he was in the Kansai. One time, he asked me, "What did you think the Japanese word for 'design' was?" When I replied, "Wasn't it design or planning?", he seemed unconvinced. After thinking for a while, I said, "Was it the nuance of expressing intention or will?" to which he responded negatively. I remember that even in his later years, he was still thinking about "What was design?

ー It was through such communication that you organised the 'The Age of Yoshio Hayakawa: The Trajectory of Osaka as a Design City' in 2002.

Yoshio Hayakawa Collection of the Nakanoshima Art Museum, Osaka.

Sugaya In 2000, the City of Osaka received a donation of more than 60 posters from Mr Hayakawa for the Museum of Modern Art (now the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka), which was to be built in Nakanoshima. The exhibition was held at the ATC Museum in the Nanko area for about a month from 1 June 2002, looking back on the trajectory of Osaka as a design city through Hayakawa's creative activities. However, the venue was 1,000 square metres and had a high ceiling, so two of his most famous posters were enlarged to about 5 metres in height and exhibited. Mr Hayakawa looked at them and said, "Designers are longing for a large format", and he liked them so much that he wanted to take them home after the exhibition, but it was impossible because they were too huge. He himself did not use computers and was negative about their use at the time. However, he did enjoy secondary processing, such as changing the colour tones and stretching the size of past his works through digital technology.

ー The 60 donated posters were selected by him?

Sugaya Yes, I understand that when he moved his workplace from his office in Akasaka to his home in Kamakura in 1998, he donated some sets of works selected by himself to Osaka City, Musashino Art University and other organisations. Later exhibitions were held at the Musashino Art University Museum and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. The posters donated to Osaka City included many of his early work for Kintetsu Department Store, Keihan Department Store and the Kalon School of Western Dressmaking, as well as a number of posters that appeared in the design magazine "Press Alto". This magazine was published in Kyoto in 1937 and attached original advertising art and graphic design in the Kansai region at the time. It is now a valuable source of information on the budding period of advertising design in Japan as well as in the Kansai region. The museum has a collection of ”Press Alto”, which is also useful as a resource

ー Mr Hayakawa must have been relieved to have his work in the museum's collection.

Sugaya However, I was contacted by someone who told me that one of the posters in the "Press Alt" collection was not to his liking and that he wanted it destroyed. It is true that there may have been something he didn't like.

Nevertheless, when we told him that as a museum we could not discard it, he said that we should then give it a big butthurt (laughs). In Hayakawa's mind, there was a clear line between what he wanted to leave behind for future generations and what he did not want to leave behind. However, we should preserve as much as possible for the future, and we cannot destroy the works and materials in the collection.

ー In ” Between Imaginary and Reality ", he says: "Graphic design, such as posters, is no longer valuable to society after it has fulfilled its role. Museums and individuals sometimes collect them, but that is after-use and their original mission is over. So I thought I would organise them and dispose of them, but someone from a museum told me that when looking at Japanese graphic design from a historical perspective, Hayakawa's works are important part of them and must be properly preserved. It is a "difficult issue". What about the works, documents and materials currently donated to the City of Osaka (now the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka)?

Sugaya Most of the donated items are posters and other printed matter and original drawings by the artist himself, with a few material items. Most of his library had been disposed of while he was still alive. We have returned the photographs, letters and albums we borrowed from him for our 2002 exhibition. The current status of the museum can be found on the website at 258 posters. Other items in the museum's collection include approximately 1,100 original drawings, 200 prints, 150 books and other items that were bound by Mr Hayakawa, 16 files of positive films, 700 unused posters, proofs, some wrapping paper, calendars, paper bags, umbrellas and other items. etc. are being sorted out.

Yoshio Hayakawa, graphic designer

ー Now, I would like to ask you about the graphic designer Yoshio Hayakawa from your point of view.

Sugaya He was born in 1917. He was good at drawing from a young age, and on the advice of his homeroom teacher, he enrolled in Osaka Prefectural Kogei High School to study design. There he met Masaski Yamaguchi and was greatly influenced by his Bauhaus-style design education, which mixed German and English.

ー According to the data, after graduation he was engaged in design work at Mitsukoshi Department Store and other companies, but was drafted twice during the World War Ⅱ, which was a very difficult experience. Then, after the war, at the age of 30, he went to work in the advertising department of the Kintetsu Department Store, where he was involved in all kinds of creative work, and in 1952, at the age of 35, he set up his own business.

Sugaya He went freelance and move his office to Midosuji-Honmachi, Shinsaibashi and Sonezaki-Shinchi. Shinchi is one of Osaka's leading shopping districts, but it was also close to advertising companies such as Dentsu and Hakuhodo, and for him it was a convenient place to strike a balance between work and play.

During this period, Mr Hayakawa was involved for many years in what is now known as CI and BI design, from the interior of the coffee shop’ G Line’, which opened in Kobe in 1952, to the logo, symbol mark, wrapping paper, matches and menu. Then, in 1961, he opened the Tokyo office in Ginza, Tokyo, on the verge of making a big move.

ー What was Osaka like in those days? What kind of presence did he have there?

Sugaya At the time, Osaka was much more powerful than it is today, with textiles being the main industry in post-war Japan. In addition to the textile industry, there were also electrical manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, department stores and railway companies, and the city was full of vitality. Hayakawa's work was going well and he was already a major figure in his 40s, receiving the 'Osaka Culture Award' at the age of 37. I have heard that in those days, if the head of a company said "Let's ask Mr Hayakawa to design", that was the decision and all the design work was left to him

ー The background to Hayakawa's move to Tokyo was probably the founding of the Nippon Design Centre in 1959, led by Hiromu Hara, Yusaku Kamekura, Ikko Tanaka and Ryuichi Yamashiro, with Tsunehisa Kimura, Kazumasa Nagai, Tadanori Yokoo and others joining the organisation. The World Design Conference was also held in 1960, and it was a time when the centre of gravity of design was shifting to Tokyo. By the way, Many designers became independent from the Hayakawa office.

Sugaya There are many people here, such as Tadahito Nadamoto,Takao Yamada, Hiroshi Kojitani, Seitaro Kuroda from K2, Naoki Hiramatsu and many others. Mr Nadamoto worked as chief of Hayakawa's Tokyo office before going independent and establishing himself as an illustrator. Mr Yamada, on the other hand, was put in charge of the Osaka office and later established his own design company, TCD, which handles major projects such as CI and branding. Mr Kuroda is more of a painter than a designer, while Hiramatsu is also active mainly in illustration.

ー When I look at the diverse line-up of disciples, I guess that Mr Hayakawa himself must have been a man with deep pockets.

Sugaya Mr Hayakawa I knew in his later years was mild-mannered, but I heard that he was frightening when he was young. When I was talking to him, I would sometimes get nervous. I can't say it well, but even though he was an Osaka native, he consistently spoke in standard Japanese, not Kansai dialect. Even to me, who was as old as his son, he called me "san" instead of "kun". I think he disliked the familiarity of Kansai-style human relationships and the familiarity of people in the industry. I think he had a modern lifestyle in mind, as well as the way he dressed. That's why he was so strict with people who was over-familiar person and undiscerning person.

The reason he moved to Tokyo was because he wanted to work on books. He was interested in designing books as a whole, not just the covers. His love of books was well-known.

ー In “Between Imaginary and Reality”, he said that designers should study design after gaining general knowledge at university.

What is individuality for designers?

ー Hayakawa's style is very diverse. His sense of colour, recognised by Mr Kamekura, his posters with beautiful women and Castori-Mincho script, which fascinated Ikko Tanaka, and his 'Shape' and 'Face' series, which have become his life's work, are truly the essence of his work.

Sugaya With regard to colour, Mr Hayakawa liked the paintings of the Navi School. I remember him talking enthusiastically about the Bonnard exhibition he had just seen. As for the Castori-Mincho, he said that at that time everything was handwritten and there was no transcription, so there was a lot of lettering, but there was no typeface for large letters, so he arranged the Mincho style in his own way. The name 'Castori' is derived from 'Castori shochu'.

ー He didn't have any particular model for the 'woman's face', but he wanted to depict a variety of facial expressions. And he didn't want to draw pictures without eroticism in the broadest sense. However, he said in 'Naniwa Juku' that he is particular about expressing prestige and inner refinement.

Sugaya That is very typical of Mr Hayakawa. I hear that he often visited Shinchi and Ginza, and looking at the ‘Faces’ series, I get the impression that such play was also a source of nourishment for his creative work.

ー Perhaps he was still attracted to hand-drawn works that honestly expressed the individuality of the person expressing them. I think it may be because his graphics are also hand-drawn that they are able to express an individuality that is instantly recognisable.

Sugaya When he made the original drawings, he freely used a variety of painting materials and tools, including gouache, ink, paint and watercolour, and he also used a wide variety of paper, including canvas, water-soaked Kent paper and cardboard. As these were manuscripts for printing, tracing paper was placed over the originals and instructions were handwritten on them. Each one of these can be seen as a reminder of his individuality and personality. However, care must be taken in storing them, for example, in a neutral paper storage box.

ー In ” Between Imaginary and Reality”, he had the following to say about 'individuality'. While accepting the reality that the advent of computers had drastically changed the nature of design, I was concerned about what would happen to the world of design when the inherent individuality and warmth that emanates from the designer's humanity was no longer necessary. Beyond that, the designer's job would simply be to make appropriate selections from computer-generated designs. This is a true prophecy of our times. In the end, I would like to introduce a part of Mr Sugaya's postscript to “Between Imaginary and Reality”.

Today, design methods are undergoing major changes, and Hayakawa has been working with an 'individuality' in his design activities that cannot be assimilated into the system. It is sometimes incompatible with the mainstream of design, and is synonymous with the designer's own 'humanity', and one of the ways in which this is expressed is as a 'physical sensibility' that is incorporated into the work. It was interesting to see how this presented another possibility that contemporary design is trying to truncate." (January 1999)

Location of Yoshio Hayakawa's main collection.

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

https://nakka-art.jp/

Interview 2

Interview 02 : Takao Yamada

Interview: 3 April 2024, 11:00-12:30

Location: TCD head office, Ashiya

Interviewee: Takao Yamada

Interviewer: Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

Overview

We visited Takao Yamada at TCD's head office in a residential area of Ashiya in the spring rain. Yamada founded the branding company TCD and is currently chairman of the company, and in his room was a drawing from Yoshio Hayakawa's 'Face' series. He started working in Hayakawa's Osaka office in 1961 and played the role of watchdog during the latter half of his tenure, before setting up his own company in 1971. Since then, he has faced design from a different standpoint from Hayakawa. Here, Yamada talks about Yoshio Hayakawa's personality, work and what he learnt from him.

Yoshio Hayakawa by Takao Yamada

Meeting Yoshio Hayakawa.

ー Thank you very much for agreeing to this interview today. First of all, please tell us how you came to work for Hayakawa Design Office (hereafter Hayakawa Office).

Yamada I was a close to Mr Hayakawa until he passed away. I joined the Hayakawa Office about five years after I graduated from Osaka Prefectural Kogei High School and began my career as an apprentice designer in the advertising department of the Hankyu Department Store in Osaka. I was asked by my senior colleague, Tadahito Nadamoto, who was already a staff member of the Hayakawa Office, if I would be interested in joining it as they were looking for a staff member for their Tokyo office. My classmate Hiroshi Kojitani was a member of the Hayakawa office and I knew what the office was like, so I decided to take the plunge and join the office. He also understood my relationship with my father, Sui Yamada, who was a member of the design department, and made me a member of the Hayakawa office.

ー Why did Mr Hayakawa move to Tokyo?

Yamada I imagine that the differences in design culture between Tokyo and Osaka - such as sterile design journalism, an unfavourable design market and a lack of an intellectual society that nurtured design - were the cause Hayakawa's departure from Osaka. Tokyo's forward-thinking and diversity must have appealed to him, too.

ー From the Kanto perspective, Osaka culture and Osaka's unique communication is fascinating.

Yamada In Osaka, people always try to maintain a gentle relationship with others, and moderate, relaxed communication is valued in greetings and conversation. The Osaka dialect is well suited to this kind of communication. However, he did not speak Osaka dialect very often.

ー At that time, many people moved to Tokyo in addition to Mr Hayakawa, didn't they?

Yamada The establishment of Nippon Design Center in Tokyo in 1959 was a great stimulus. Besides him, Ryuichi Yamashiro, Toshihiro Katayama, Kazumasa Nagai, Tsunehisa Kimura, Ikko Tanaka and others moved to Tokyo, and it was a time when Osaka became lonely.

ー But after he moved to Tokyo, he often came to Osaka.

Yamada He came to Osaka to work with clients from the past, such as the Kalon Institute of Western Dressmaking and the café 'G line' in Kobe, and to produce solo exhibitions. Among other things, the whole office took up the challenge of participating in the nomination competition for the design of the symbol mark for the 1970 World Expo.

Hayakawa in the West, Kamekura in the East.

ー At the time, it was known as 'Hayakawa of the West, Kamekura of the East' or 'Hayakawa for colour, Kamekura for composition', and I hear that the two of you were the two greatest graphic designers of that time.

Yamada Kamekura's designs were characterised by logic, structure and persuasiveness, and he was involved in national projects such as the Olympics and Expo '70, as well as work for large corporations such as Nikon and NTT. In contrast, Mr Hayakawa was rarely approached by large-scale projects or large companies because of his style, but was often commissioned by local companies and people close to him who were attracted to him. The metaphor "Hayakawa for colour, Kamekura for composition" could be replaced by "Hayakawa for sensibility, Kamekura for logic", and in this sense they were also twin peaks. I learnt a lot about reason and sensibility in the designs of both professors.

ー What you just said is very interesting.

Yamada Design, which was considered commercial art, changed dramatically after the World War II. The lifestyle culture and advertising design introduced by the American magazines brought in by the Occupation Forces were a great stimulus for the commercial designers of the time. On the other hand, they were also fascinated by the rational and sensitive designs of Raymond Loewy and Saul Bass. These overlapped with Kamekura's designs. On the other hand, Hayakawa's style was emotional, poetic, nuanced and painterly. This was probably due to the literary sensibility and human relationships within him.

ー How did you perceive Hayakawa’s Design, Yamada?

Yamada I think his graphic design is close to the world of Haiku poems. He was very skilled at abstracting the object of expression to the utmost limit. His designs were simple, yet had breadth and depth, just as Haiku poems strike one's heart with their finely honed language.

ー On the other hand, he was actively holding solo exhibitions at galleries in Osaka.

Yamada In part, holding solo exhibitions was a way of raising funds for the Osaka office. The Imabashi Gallery and Ban Gallery, which no longer exist, were favourable to graphic designers and encouraged them to hold solo exhibitions, and the ’Shape’ series is one of the works for them. An attempt was made to express geometric shapes so that the staff of the office could share the work, and this was continued.

Silk printing was ideal for creating small batches of work to be sold like prints at solo exhibitions. Once his original drawing was completed and the printing process was underway, I would enter the site and witness the whole process. It was very hard work on site to protect his image.

ー How is Hayakawa's design born? What kind of work did you do there?

Yamada At the time, the his work began with drawing on panels of water-soaked Kent paper covered with Japanese Mino paper. The drawings were pencil drawings, which were used as a rough sketch, and the staff peeled off the pasted Mino paper with a cutter knife and painted the poster colour into it. Drawing was always direct and there was no such thing as idea sketches or rough sketches. His work always included attention to materials. There is an anecdote that when the painted poster colour was drying in the sun, it started to rain and the stains on the screen were left in place as they were interesting. My job was to take the hands of staff with little practical experience and watch the whole process.

ー So artisanal manual work and physical sensibility were also important elements in design?

Yamada In those days, there were no convenient tools such as computers, and all designs were drawn by hand. The tools used were dividers, compasses, drafting machines such as a razor blade and rulers, and for colouring we used faceted brushes, flat brushes and slotting brushes. Expressive techniques were essential for graphic designers as a profession.

Mr Hayakawa was not very good at the craftsmanship of drawing fine lines using a groove holder, and tools such as a crow's feet and a curved ruler were useful for expressions that required precision. While many designers favoured precision expression, he enjoyed the strength and dynamism of freehand and valued the pictorial expression of his work.

ー What you just said reminded me of the 'Castori-Mincho' and 'Face' series.

Yamada The typeface known as "Castori-Mincho" is unique by him. Basically, the horizontal bars of the characters are drawn in Ruling Pen, while the other vertical bars, tome, ‘hane’ and ‘harai’ were drawn freehand, giving the characters a sense of movement and individuality. Without any disrespect, this might be a masterpiece created by a certain clumsiness on the part of him.

The 'Face' series is another work that only Hayakawa could have done. The delicate expressions and beautiful colours are the world of a woman in love. Strangely enough, all the women depicted in the series remind me of Mrs Hayakawa. I may be the only one who feels this way.

What Yamada learnt from Yoshio Hayakawa.

ー Now, we would like to ask you about yourself. What made you leave the Hayakawa Office?

Yamada I felt that my work was worthwhile and that my life was worth living. However, the Osaka office became difficult to maintain as the Hayakawa activities moved to Tokyo. I consulted with Yozo Kobayashi and decided to quit. I had been with the Hayakawa office for 10 years and was over 30 years old. My resignation triggered the closure of the Osaka office and I feel sorry for my colleagues.

ー Did you start working freelance?

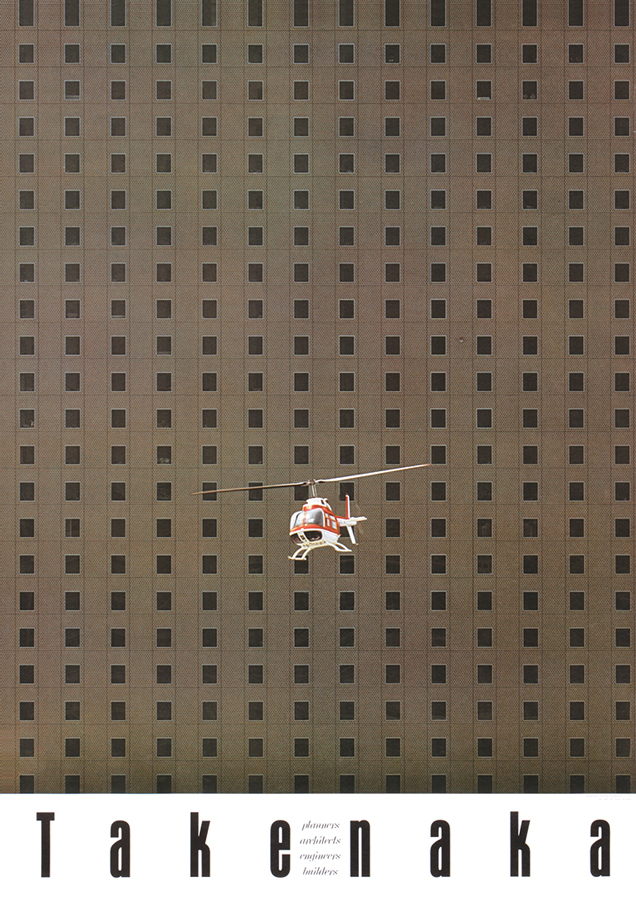

Yamada At first, I looked for a place to work and raised the nameplate of the "Takao Yamada Design Office". After a while, I did a small job for Takenaka Corporation, which was introduced to me by a classmate from Osaka Prefectural Kogei High School. The turning point came in 1977, when a corporate poster designed with the motif of a building which Takenaka had constructed was featured in an exhibition at the New York Art Directors Club, and at the same time received a gold and silver award and was included in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Since then, I have been consulted by companies and governments such as Asics, Matsushita Electric Works, Kobayashi Pharmaceuticals, Nankai Electric Railway and Hakutsuru, as well as Takenaka's brand design work. Then, with the help of friends, the organisation expanded and changed its name to ’TCD’.

Takenaka Corporation corporate posters, now in MoMA's permanent collection.

ー The company name 'TCD = Total Cultural Dynamism' is very innovative.

Yamada This is the concept behind the current TCD. Companies change in the same way as people grow. People and companies alike should change and grow, even if they have the same name. In order to share this reality with our employees, I have reviewed the meaning and concept of 'TCD' several times. The same 'TCD' has changed from 'Total Creative Development' at the start to 'Think Creative Design' and then to 'Total Communication Design'. The current concept is 'Total Cultural Dynamism', which includes the wish that everything we do is cultural and powerful. I think this idea originated from my experience at the Hayakawa Design Office.

ー Finally, what was Mr Hayakawa like for you and what did you learn from him?

Yamada He was a superstar in the design world and was socially recognised, so he was blessed with a great variety of work. As a designer, he had a wide range of sensibilities and was skilled in application, but he was also rational. I think it was only under him that I was able to solve the difficult problem of balancing sensitivity and logic. It was a valuable experience for me to be able to assist him in his work in close proximity.

Mr Hayakawa passed away at the age of 92 when I was 70, but I respected and loved him very much. His rare personality captured people's hearts and did not let go. I continue to believe that the personality and work of Yoshio Hayakawa, the designer, were shaped by his youth in the harsh times of World WarⅡand defeat, and that this was also his charm.

ー Thank you very much for your valuable talk today.