Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

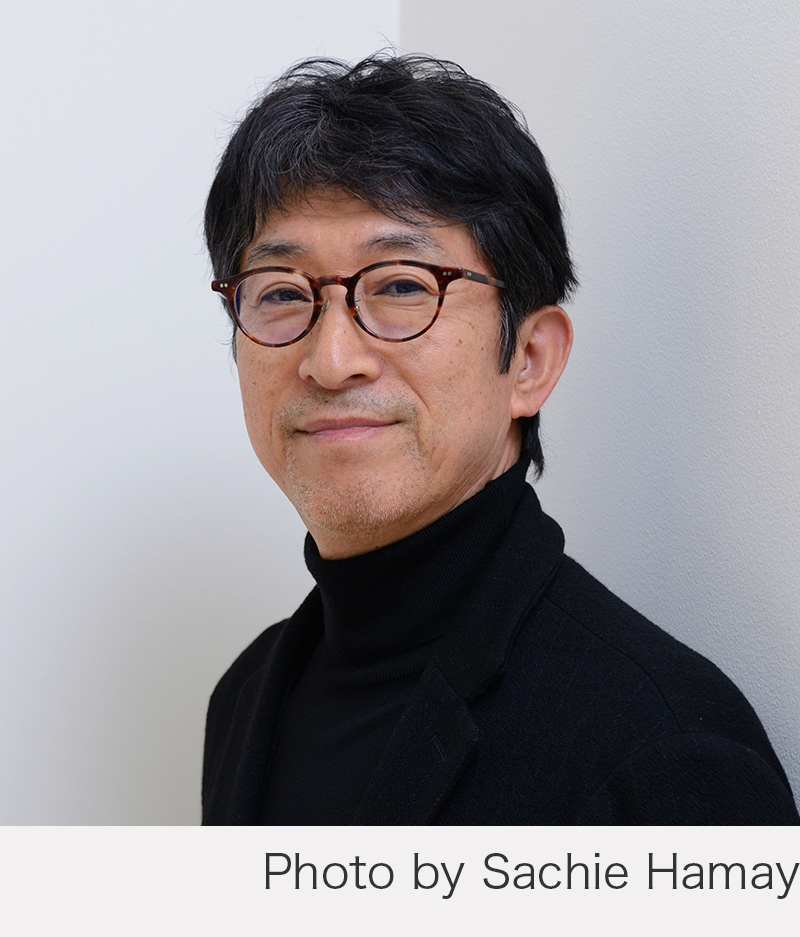

Masaaki Hiromura

Graphic designer

Interview: 18 September 2024, 14:00-15:30

Location: Hiromura Design Office

Interviewee: Masaaki Hiromura

Interviewer: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Masaaki Hiromura

Graphic designer

1954 Born in Aichi Prefecture

1977 Graduated from Musashino Art University Junior College of Art and Design

Joined Ikko Tanaka Design Office

1987 JAGDA New Designer Award

1988 Established Hiromura Design Office

2009 Mainichi Design Award

2010 Professor, Department of Design, Faculty of Arts, Tokyo Polytechnic University (-2018)

Good Design Award Gold Prize

2011 Representative Director and Creative Director,

General Incorporated Association Japan Creative (-2021)

2016 Visiting Professor, Department of Design, Tama Art University

2019 Visiting Professor, Nagoya Zokei University

Description

Description

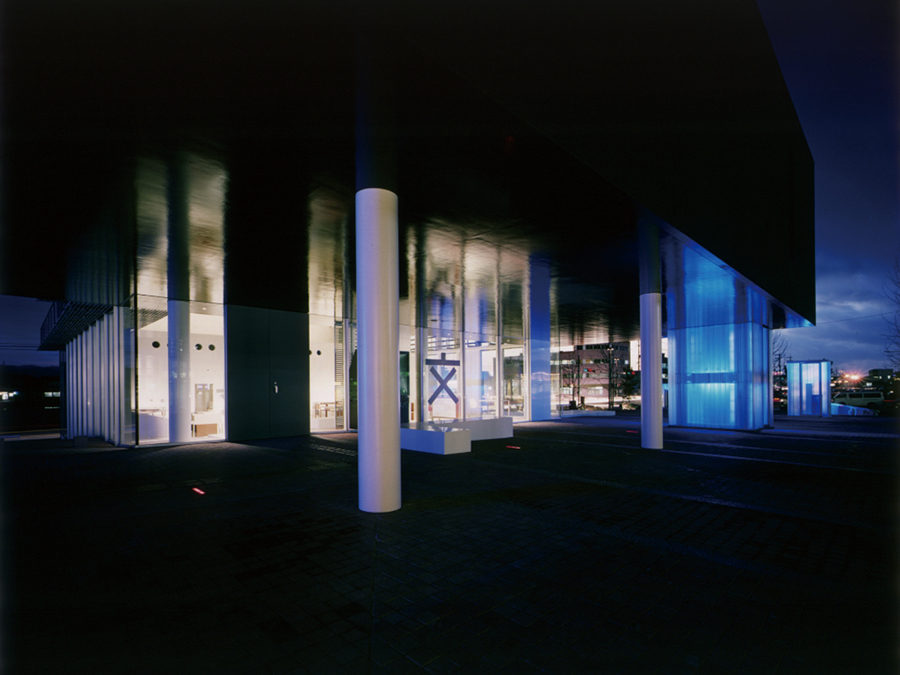

Kaoru Kasai, who is also involved in graphic design, describes Masaaki Hiromura's work as follows. ‘The pictograms in a lot of his work are tranquil and warm. They are clear, intelligent and colourful. Hiromura's designs always support someone. Now, Hiromura must be experiencing the happiness of design, which is complete only when it is in conjunction with people and things’ (ggg books-81). 17 years ago, Kasai's message was given to Hiromura, and his designs have made great strides while preserving their essence. Hiromura specialises in ‘areas of graphics that are more theoretical and mathematical than sensory’ and in ‘design with a clear purpose (sign) that can be designed while searching for a rationale that can be divided by theory’. In fact, Hiromura's VI and CI, sign design is expanding from public buildings to commercial facilities and temporary exhibition venues.

And its design features a ‘Sacherlich appearance’. In other words, it is immediate. Graphic materials include letters, figures, colours and illustrations, but Hiromura doesn't fiddle around with them, but combines them in surprisingly simple ways to create graphics and signs. Yet there is no rigidity, but rather an exquisite spoon-feeding of freedom and playfulness! This characteristic of Hiromura's design is probably the reason why it is accepted by architects who are space supremacists and clients who are looking for a sophisticated space.

Hiromura has begun to break new ground in sign design. It is a sign design that ‘requires us to go out and get what we need (information)’, which is a breakthrough in today's flood of information. It may be a new kind of graphism that incorporates what Masato Sasaki calls ‘affordance theory’ and does not rely on letters, shapes or colours. We cannot help but have high expectations for the future work of Masaaki Hiromura, who has established ‘signage’ as a field of graphic design.

Masterpiece

Representative works

1989 Issey Miyake im VI design

1996 Iwadeyama Junior High School sign design (renamed Osaki Municipal Iwadeyama Junior High School in 2006 following the merger of municipalities)

2000 Takeo Mihoncho Honten General AD, VI and sign design

Future University Hakodate UI, sign design

2001 The National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation CI, sign design

2006 Commemorative mark for the 1300th anniversary of Nara Heijo-kyo Capital

2007 Yokosuka Museum of Art VI, sign design

2009- 9h nine hours Kyoto Teramachi VI, sign design

2011- Loft Yurakucho General AD, sign design

2012 Sumida Aquarium VI, sign design

Japan Creative exhibition CD, AD (-2021)

2015 Seibu Shibuya Department Store renewal General AD, sign design

2016 National Taichung Theater sign design

2019 Tokyo 2020 sport pictograms development

2020 Artizon Museum sign design

2022 Ishikawa Prefectural Library, sign design

2024 The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka VI, sign design, exhibition graphics

TODA BUILDING VI, sign design

Book

"New Generation Graphic Designer, Hiromura Masaaki",

Guangxi Arts Publishing House/China (2000).

"SPACE GRAPHYSM", Rikuyosha (2002)

“What design can do. What design should do.", ADP (2007)

World Graphic Design Series ggg Books 36, "Masaaki Hiromura", Ginza Graphic Gallery (2007)

"JI BORN", ADP (2009)

"From Design To Design", ADP (2015)

Interview

Interview

Even in graphics,

I liked areas that had theoretical and mathematical elements

rather than those that were intuitive.

The road to becoming a designer

ー How did you decide to become a designer?

Hiromura When I was a senior in high school, I had been recommended to enter the Faculty of Economics at a certain university, but I was conflicted about whether this was really the right choice.

I was looking for an opportunity to change my life. It was then that it suddenly occurred to me that ‘design’ might be a good idea. ...... I then persuaded my parents to let me waste a year and enrolled in an art preparatory school. However, I was surprised by the high level of ability of the students there, all of whom had been studying practical skills for years with the aim of going to art university, and I learnt how naive I was.

ー Most people give up at that stage.

Hiromura I changed my course of study after talking to my parents against my university recommendation, so I can never say that I changed my mind there again. In the end, I went to a preparatory school for a year, went to Tokyo and enrolled in the graphics department of Musashino Art University Junior College of Art and Design. At the time, I was thinking that I could just transfer to a four-year course when I graduated.

ー Why did you choose graphic design?

Hiromura The reason was that graphics had a wide opening. But when I started studying, I discovered how interesting graphics could be. Among them were two-dimensional composition, colour composition, typography and optical art design. Optical design was pioneered by Kazumasa Nagai and was very popular at the time. I was fascinated by such things, so I liked areas of graphics that had theoretical and mathematical elements rather than sensory ones.

Encounter with Ikko Tanaka

ー So the germ that led to the you of today was already there when you were at university? What happened after that?

Hiromura I tried my best in my own way for two years, but I was unable to transfer to a four-year course, so I entered a specialised course. That's when the turning point came. Katsuhiro Kinoshita, who was a year my senior and had won various awards since he was a student, had already joined the Ikko Tanaka Design Office (hereafter Tanaka Office) as a staff member. That's when Mr Kinoshita approached me and I got a part-time job in 1975. That was when I met Mr Tanaka for the first time.

At the time, the demand for design was increasing rapidly, with the launch of magazines and the opening of commercial facilities, and the Tanaka Office was extremely busy with a lot of work. However, my work was not in design, but in helping him with his hobbies. As it happened, our hobbies were close and I was able to continue working part-time.

ー It's a very Hiromura’s episode. What are your common interests?

Hiromura Mr Tanaka was a music hobbyist and a regular reader of “Stereo Sound”, a magazine specialized in audio and audio-visual equipment. He would look at the magazine and buy the latest audio equipment featured in it, and it was my job to tune these devices. Incidentally, the company emblem of Ishimaru Denki, where I went to buy parts, was designed by Tanaka, and the wrapping paper and other graphics were done by Makoto Wada. After a while, he told me to get a driving licence, so I became a driver to the newly completed villa on Lake Yamanaka. That is how I spent four or five years in the office.

ー I can't imagine it at the moment, but I got the impression that you were not a proactive person.

Hiromura Staff of Tanaka Office take an entrance examination before being officially hired, but I continued working part-time after graduation without being officially hired, and it took me quite some time before I was entrusted with design work. Counting from my part-time job, I was with the Tanaka Office for 13 years.

When I was a student, Ikko Tanaka, Kazumasa Nagai, Shigeo Fukuda and Tadanori Yokoo were known as the ‘Graphic Four’, representing the new generation. From that time onwards, Mr Tanaka was special, and I heard that during his time at Nippon Design Center, a special aura leaked out from his room and that some part-time workers in Tanaka office had a nervous breakdown and had a stroke. I, however, was not familiar with such a situation, so on the contrary, I think I was able to behave comfortably.

ー You were eventually entrusted with the graphic work as well, weren't you?

Hiromura In the 1970s, the Tanaka office was a really fulfilling time. Under these circumstances, he separated ‘corporate work’ and ‘cultural work’, and I was in charge of corporate work. I designed for Seibu Department Stores, Seiyu Stores and Family Mart, which Mr Tanaka was asked to do by Seiji Tsutsumi of the Saison Group, and later on for MUJI, where I travelled to sales floors and sites across the country to design everything from packaging materials to shop displays and pop-ups. The number of design items was enormous, and the schedule and budget were very strict, so I was trained considerably. Mr Tanaka was more focused on ‘cultural work’, and his method for ‘corporate work’ was to decide on the main direction and leave the rest to us on site. The Saison Group was growing at the time and I was happy to be able to take on new challenges. But I wasn't doing ‘cultural work’, so I was a designer without a culture in the Tanaka office.

ー But those experiences have led to the work you do now.

Hiromura Indeed. Because my corporate work included not only graphics but also sales floor design. Mr Tanaka entrusted me with most of the sales floor design, and that experience is the basis of my current work.

ー Tanaka Office at that time did a lot of work for the Saison group?

Hiromura At the time, the Saison Group had eight core companies, so I think 70% of our work was Saison-related. In terms of cultural work, clients included “Ryuko Tsushin”, the Seibu Museum of Art, Issey Miyake and JAGDA. I started as Mr Tanaka's hobbyist and was finally put in charge of design work, and finally became chief in my sixth or seventh year. There are many people who entered Tanaka's office, but surprisingly few who worked there for a long time. Tetsuya Ota, Kenichi Samura, Tokiyoshi Tsubouchi, Katsuhiro Kinoshita, myself and Kan Akita, who later passed away, followed. There are 11 people who can be said to have come from the Tanaka office.

ー What did you learn about design from Ikko Tanaka?

Hiromura Mr Tanaka was able to use his dual skills as a corporate director and a graphic artist in an exquisite way. His designs were carried out very sensitively, but his attention to millimetre-scale figurative differences and colours was unparalleled. His collection of coloured paper, collected from wrapping paper and other sources, was renowned. We, the staff, were able to gain multifaceted experience, from the exquisite and sensual design trained in graphic arts to commercial design such as corporate advertising.

When he had time, Mr Tanaka cooked, organised the bookshelves and wrote thank-you letter for the books he donated. He would get furiously angry at me if I had anything that upset him, whether it was my work or my behaviour, and it was a tense time for me, but he also taught me the importance of searching for the essence of things, and to do so, it was important to study and gain experience without stint. Every Monday morning we reported on what we had done over the weekend. Film, theatre, concerts - he was very pleased when he found them interesting.

After becoming independent

ー Why did you become independent?

Hiromura In 1988, twelve years after I joined Tanaka Office, the office was unusually busy, so Mr Tanaka decided to set up a subsidiary company. The name of the new company was IKKS and I was put in charge of the whole company, but I had to undergo a design check by him. However, I was so busy that sometimes I couldn't show them to him, and he found out about it.

In the middle of the friendly banquet at Masayoshi Nakajo's Mainichi Design Award party, a red-faced Mr Tanaka appeared at the venue and came straight to me, saying in front of the guests, ‘Immediately resign from my company’. I understood the reason, said ‘I understand’ and left the venue, and went around greeting clients the next day. I had no problem quitting because it was Mr Tanaka's company, but only president Masao Kiuchi of MUJI said, ‘I was the one who ordered it, so you could not just quit’. So I continued working for MUJI for a while. Then, MUJI invited me to participate in a four-company packaging competition, which I won, so I did the packaging and advertising work on my own.

At that time, Mr Tanaka, Takashi Sugimoto, Hiroshi Kojitani and Kazuko Koike were the directors of MUJI, and they decided on the overall creative concept. However, in 2000, Mr Tanaka suddenly said that he was quitting after 20 years, and Kenya Hara was appointed his successor, and I also quit. However, shortly after that, Mr Tanaka passed away....... Looking back, I wonder if he had a premonition about what was to come.

ー How did you develop work outside of MUJI?

Hiromura For a while after independence, I did a lot of work for MUJI. I think there was a time when it accounted for 80% of my total work. From there, I gradually developed my business on my own, and through various connections, I gradually began to receive other commissions.

Collaboration with architects

ー How did you get involved in sign design in collaboration with architects?

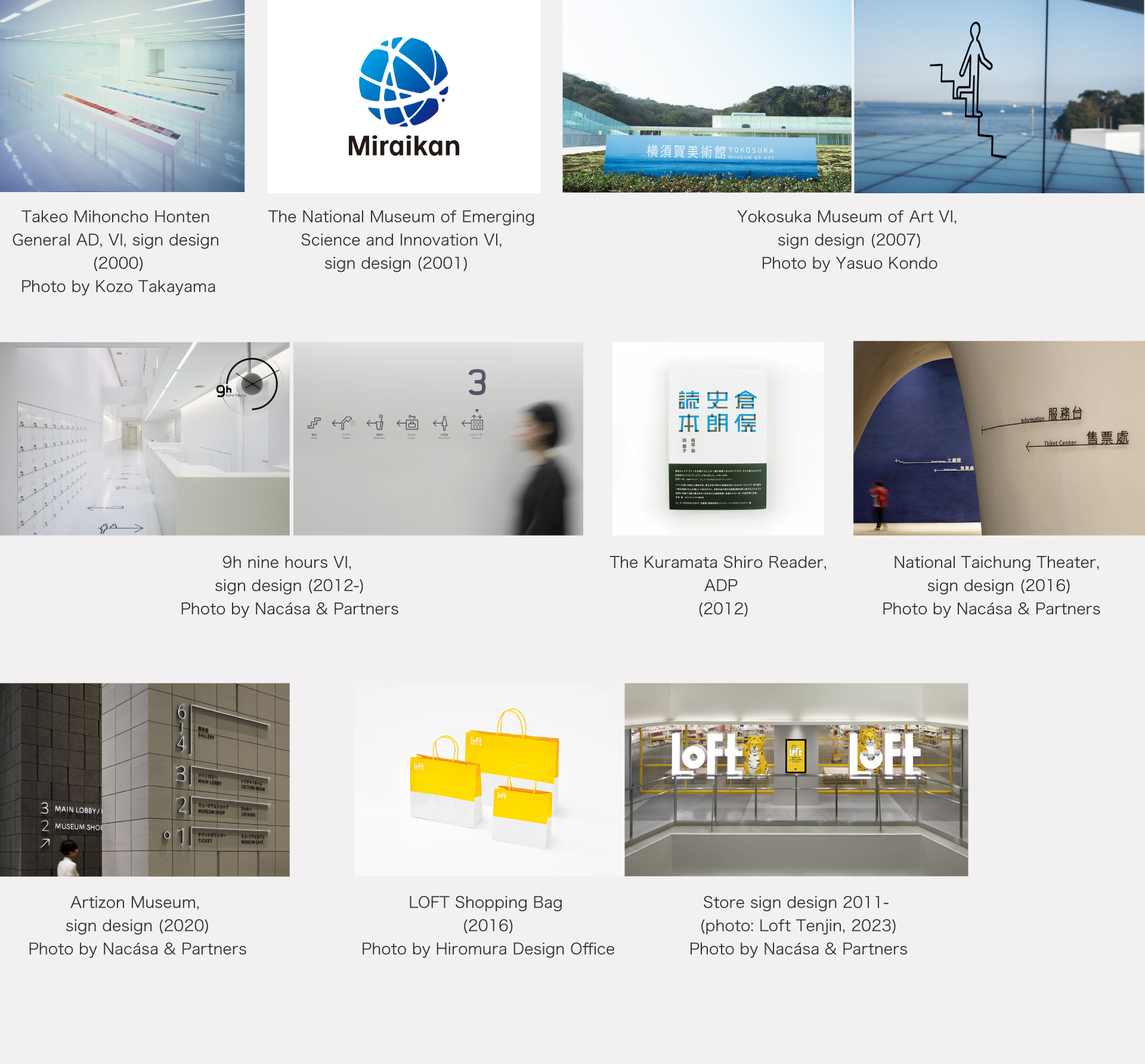

Hiromura In 1995, Riken Yamamoto designed a project called ‘Iwadeyama Junior High School in Osaki City(renamed Osaki Municipal Iwadeyama Junior High School in 2006)’. Mr Yamamoto was known for designing housing complexes, but this was his first time designing an educational facility, so he wanted to collaborate with a designer for furniture, lighting and sign. He told us: ‘I want an idea with an impact that will open up a hole in my architecture’.

His design was a plan in which the walls on the corridor side of the classroom were partitioned off with movable fittings, which could be opened and closed to create an open space with a high degree of freedom. Then I came up with two ideas. One was to incorporate the design intent into the sign design and have people experience it, and the other was to design the sign as a system that runs through the entire school. He agreed to this idea. Therefore, signs for classroom numbers, directions, locker numbers, etc. were expressed as dots on the fittings, and an attempt was made to ‘integrate the fittings with the architecture’, where the fittings became the signs as they were. The dots blur the boundary between the interior and exterior of each room, emphasising the sense of openness that he was aiming for.

This project gave me a real sense of the interaction between sign and architecture when it was designed as a system, and this was a great stimulus for me. I also discovered new graphic design possibilities that I wanted to explore as my own theme. This led me to collaborate with many architects, including Mr Yamamoto.

‘Iwadeyama Junior High School in Iwadeyama Town (renamed Iwadeyama Junior High School in Osaki City in 2006)’, new sign system integrating fittings and dots.

Photo by Mitsumasa Fujitsuka

ー When you were at university, you said that you ‘liked areas of graphic design that were more theoretical and mathematical than sensual’, and this became clearer when you met him?

Hiromura Yes. After the bursting of the bubble in 1991, Japanese design was in a strange situation compared to the West, with a self-reflective atmosphere. In the advertising industry, there was a focus on artistic design that straightforwardly expressed a rich sensibility, as typified by Makoto Saito. I didn't have those ability. When I was searching for my own design, I met Mr Yamamoto and began to work seriously on sign design. I began to think that although graphics had the restriction of being two-dimensional, expression was limitless, and in addition, sign design was interesting because it went back and forth between two and three dimensions because it had the fetters of functionality.

ー Sign design became the core of your work.

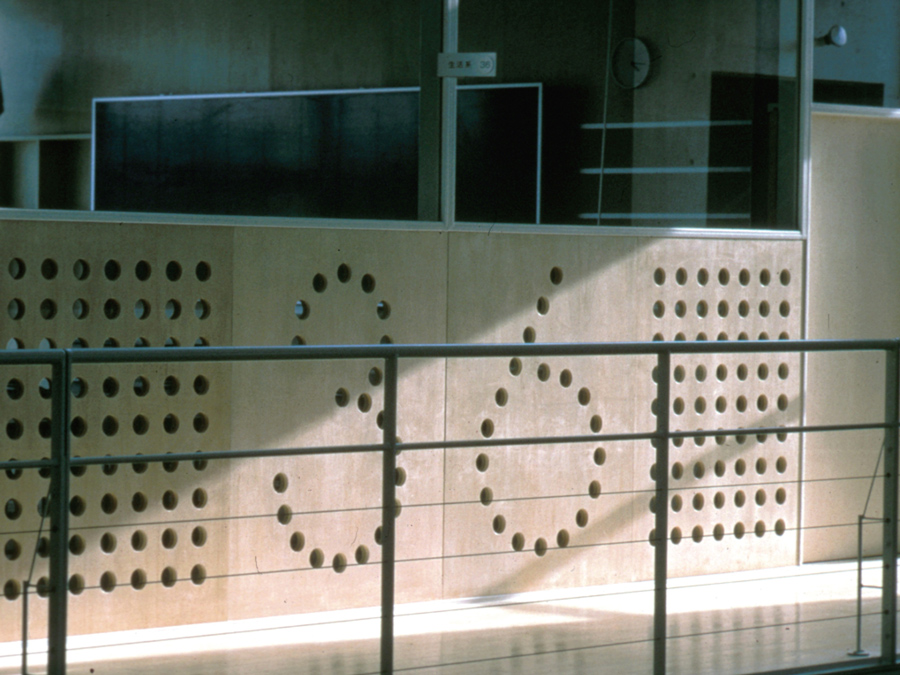

Hiromura Although the number of requests for sign system work has increased, there has also been a lot of trial and error. ‘Big Heart Izumo’ in Izumo City, Shimane Prefecture, where I worked with Kazuhiro Kojima of Coelacanth and Associates, was a local cultural and exchange centre consisting of meeting rooms and a cultural salon. The design I came up with here was to express the facility's room names using a single Kanji character, for example, ‘会’ = meeting room and ‘文’ = cultural salon. Izumo City was a place of faith known for its mythology, with the Izumo Taisha shrine, so I thought it would be appropriate to use ideographic Chinese characters to express its characteristics. I designed solid characters using straight lines to be in line with modern architecture and placed them in the space. However, when I found out the opinion of Toyo Ito, who later came to observe the project, I realised the importance of harmony between architecture and signage. I began to think that I wanted to realise a sign that had warmth and spoke to people's hearts.

‘Big Heart Izumo’ was an impressive large ‘Kanji’ sign, improvised in the space.

Photo by Hiroyuki Hirai

ー You and Mr Ito have also designed signs for the ‘Ibaraki City Cultural and Childcare Complex ‘Onikuru’ in Osaka, etc. Do you often collaborate with Mr Yamamoto as an architect?

Hiromura Yes. I have worked with Mr Yamamoto on many projects, including ‘Saitama Prefectural University’, ‘Future University Hakodate’, ‘Shinonome Canal Court CODAN Block 1’, ‘Yokosuka Museum of Art’, ‘Tianjin Library’ and ‘Nagoya Zokei University’, etc. I imagine that the reason I have been able to work with him so much is because of the good compatibility between his architecture and my graphics. I would be happy if I could add graphic elements that correspond to the concise and dignified architecture based on his theory.

ー That's right.

Hiromura Since I was a student, I've been designing while searching for a rationale that can be divided by theory, so I'm suited to sign design that has a clear purpose, and I think it's fine if I can play freely after fulfilling the function.

ー What is the most impressive work you have done outside of architecture?

Hiromura In terms of being deeply involved in the development of a new type of business, we have been involved in the capsule hotel ‘9h nine hours’ since 2009. The name ‘9h’ is based on the fact that the minimum amount of time required for minimal activities in the hotel, such as sweating, sleeping and getting ready, is approximately nine hours. The operation of this hotel is almost entirely unmanned. Information that would normally be explained by staff, such as how to use the rooms (capsules), amenities and almost all the rules in the hotel, have to be signposted. Furthermore, we wanted to express the idea and innovation of the new 9h business model. I think the project was a successful fusion of space, function and graphics, which created a synergistic effect.

The concept of "9h" was directly translated into visuals.

Photo by Nacása & Partners

ー What aspects of the design did you pay particular attention to?

Hiromura Sign design for train stations and airports, where people of all ages and languages can quickly understand and move around. We aimed for signs and pictograms that are simple and can be understood intuitively from the diagrams, colours and locations where they are placed.

Outside of routine work.

ー You have regularly published ‘SPACE GRAPHYSM’ and ‘What design can do. What design should do.’ , ‘JI BORN’ and ‘From Design To Design’. What is the timing of your publications?

Hiromura The first opportunity came from Ikko Tanaka. I had been a little distant from him since his rage incident, but when he looked at my work in my tenth year of independence, he said I should write a book, even though he had no comment on my designs. I wondered if he recognised my design in his own way, so I immediately went to Keiko Kubota of ADP for advice.

Kubota The first time I met you was when Takashi Sugimoto introduced you to me when he produced the book ”Shunju” in 2004.

Hiromura Ms Kubota readily agreed to publish the book, and with an exhibition planned for October 2002 at Design Gallery 1953 in Matsuya Ginza, I made preparations to publish the book at the same time. However, Mr Tanaka, whom I most wanted to have a look at it, passed away suddenly in January. Since then, I began to think that I had to record my work.

ー In ‘SPACE GRAPHYSM’ you analysed the possibilities of graphic design in space from the four concepts of ‘system’, ‘graphism’, ‘presentation’ and ‘visual identity’. The third book, “JI BORN”, is based on the history of letters, and looks at the relationship between the five human senses and instincts and letters, making it a book that can be enjoyed by non-designers as well.

Hiromura As I wrote in the introduction to” JI BORN”, graphic design has evolved by combining the visual elements of ‘letters’ and ‘diagrams’ to create new expressions and messages. As a designer, I have been involved with ‘letters’ and wanted to review them from a scientific angle, so I collaborated with the editorial director Kuniyasu Kato to compile this book.

ー Not only signs, but also your work is often simple and immediate, combining letters, arrows, lines and shapes, which is a result of his research for the” JI BORN”. Putting together a book is of course a good influence on the design work?

Hiromura Yes, it does. At first, I didn't think about it deeply, but I learnt by taking methods such as publishing and exhibitions when I hit upon a theme I wanted to organise my thoughts or research.

ー One of these was ‘Junglin’’, wasn't it?

Hiromura Yes. Junglin’ was a project that focused on the theme of ‘discovering design hint in everyday life’. ‘Junglin’’ is a coined word that combines ‘ing’ with ‘sequential(junguri)’, and we held three exhibitions between 2011 and 2018. Sign design is about finding the starting point of people's behaviour, such as whether it communicates something to people, how people notice it and what people follow, and we also experimented with this. We thought that if we looked at the moments in people's daily lives when their awareness and minds are triggered, new ideas and designs would emerge. In other words, we look for ‘triggers’.

Color-batons(2011)

Photo by Nacása & Partners

Image presented at the exhibition of Junglin’.

Slice (2014) Shot by Akihire Yoshida VP amana inc.

ー ‘Japan Creative’ (hereafter JC) is a project that explores the very origins of ‘Japanese creativity’ in various parts of Japan and connects them to the future. It started just in 2011, the year of the Great East Japan Earthquake, and was led by Mr Hiroshi Naito and you.

Hiromura ‘JC’ started as a project of the Seibu Department Store, and in 2011 it made a new start as a general incorporated association. Everyone took it seriously because of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Its activities are aimed at widely disseminating the ‘new value of Japanese craftsmanship’, developing products through collaboration between Japanese manufactures and creators in Japan and abroad, organising exhibitions and talk events, and recording and publishing. In the 10 years I participated in the project, we developed 24 projects, held 10 exhibitions in seven countries and continued the talk sessions on the future of Japanese craftsmanship for seven years. What I wanted to focus on was to explore the essence of ‘creativity’. I was empowered by the energy of the activities of all kinds of people, regardless of generation and nationality, and I enjoyed the projects.

During 2012-21, the project's results were presented in various parts of the world, including at Milan Design Week.

Photo by Nacása & Partners

ー Mr Naito states in the 10-year history book of JC that ‘true communication beyond words has taken shape’. It is wonderful that you organise research activities and exhibitions in parallel with your routine work.

Hiromura Actually, I am currently researching the tentative concept ‘Hypothesis and Temporary’ and plan to publish it and hold an exhibition at Gallery A-quad in Takenaka Corporation's Tokyo head office. The theme ‘Hypothesis and Temporary’ is a concept that is an extension of ‘Junglin’’. This involves hypothesising about the flow of people's behaviour and actions, analysing and testing these hypotheses with video and photographs, constructing them as an exhibition, and then publishing them in a book.

ー ‘Hypothesis and Temporary’, the tentative title alone is exciting.

Hiromura For example, signage plans are always required to be strong and durable, but are they really? I make a hypothesis. Then, when it comes to signs, for example, the venue sign for the ‘World Design Assembly Tokyo 2023’ only needs to be in place for a few days during the event, so a light and easy-to-remove design is better. In other words, it needs to be temporary rather than sturdy. In this way, ‘Hypothesis and Temporary’ became more and more connected, and we thought it was a topic worth researching. Sign design has many rules and regulations, such as font size, colour, JIS (Japanese Industrial Standards), etc., and there are many cramped areas. However, the places where signs are actually installed are very diverse, including the colour and material of the wall, the position of the sign, the line of sight, and so on, so I thought it would be good to be more free and sensible.

ー When I hear your story, I feel like it has something in common with Naoto Fukasawa's "WITHOUT THOUGHT."

Hiromura That's exactly right, I was very moved and inspired by ‘WITHOUT THOUGHT’. The approach that Mr Fukasawa aimed for, which is to analyse the essential psychology and behaviour hidden in people's everyday lives, and to design on that basis, is a common one. It is important for signs to be understood without logic. For example, there is a hypothesis that humans subconsciously look for ‘human faces’, and we want to consider the reasons why we gaze suddenly at an arrow or a single line from the angle of sign design.

ー I've heard that babies respond to ‘faces’.

Hiromura The things I have just mentioned may be fundamentally imprinted in human beings. If so, sign design could be simpler, with a different approach. These days, we are inundated with information and even digital signage is not as impactful as it used to be. Sign design should be about getting the information you need from here. That's the kind of hypothesis I'm going to conceive at the exhibition.

ー What do you keep in mind on a daily basis?

Hiromura I always summarise the parts of a book that interest me, and then I organise and visualise them in writing through my own empirical experiments. By publishing a book, my thoughts become fixed in my mind, and when I go through various contradictions, I can stop at a certain moment and move on to the next stage. Publishing in particular may be a very human desire to leave a trace of something.

ー For you, is there a difference between two-dimensional graphics and three-dimensional spatial design?

Hiromura Spatial design is a ‘temporary’ form, as I work on exhibitions and events that have a limited time frame. So it's a game of how interesting you can make things within spatial and temporal limitations, which is different from architecture, which requires permanence. When I design spaces, I consider the span of time in three stages: signage design, exhibitions and short-term events.

ー You also made headlines with the design of the ‘Tokyo 2020’.

Hiromura This project was a team effort and took about two years to develop. We considered a number of ideas to express the current ‘Tokyo’, and finally came up with a proposal that inherited and evolved from the sport pictograms that was first officially adopted for the Tokyo 1964 Games. The goal was to achieve a brevity that anyone could understand without language, while at the same time maximising the appeal of dynamic athletes and how to depict the highlights of a moment in modern athletics.

Pre-digital and post-digital.

ー Your generation experience the pre-digital and the post-digital design, what are your thoughts on this?

Hiromura I think it was around the year 2000 that digitalisation really took off, and the effects of this are evident in my own designs. Today, the process of selecting and verifying the means to realise the finished image is important. The thing to bear in mind with digital is that although it can be made to look like it, there is something uncomfortable about it, or it doesn't give a sense of depth. ...... This can be reflected in the presence. It would be good if the designers themselves had a range and could decide whether this is something that can be done digitally or by hand. Even if technology evolves, you always have to think from that perspective. I think it is the same with art.

ー I recently summarised Yoshio Hayakawa, who writes in his book, ‘In the age of computer design, I worry about what on earth will happen to the world of design when the inherent individuality and warmth that exudes from the designer's humanity is no longer necessary’. Digital seems to be able to do everything, but in fact, everything is pre-programmed, including line, colour and movement. In the end, I wonder if the designer's job will be different from manual skills when it comes to ‘choice’.

Hiromura It is important to have a certain degree of image at the beginning. Students and young designers have to try all kinds of methods and gain experience. This is the same for both digital and analogue. Once you know to a certain extent, you will be able to express the image you want in both analogue/digital (or hybrid). However, as you say, in the case of digital, there are tens of thousands of options to decide on a single colour, so it is difficult to make a choice. This is because you don't have an image at the beginning.

ー On the other hand, it is important for you to properly convey the image in words.

Hiromura Of course. The choice of words and the context are important, so I am learning a lot.

ー Words too, but what about shared experiences? Does the accumulation of the same place, time and shared experience have an impact on design?

Hiromura Very much so. What is important before that is what kind of experiences you have in early childhood. If possible, by the time they graduate from primary school, they should be developing their senses through a variety of experiences. Experiences and memories of contact with nature and culture can deepen our understanding of others and trigger dialogue, and I believe that design is based on such experiences.

ー Before the digital age, ‘places’ such as ‘Tokyo Designers Space’, for which Ikko Tanaka made great efforts, were places for exchange and triggers for empathy and conversation, which had the aspect of enriching design. Now, however, each designer is fragmented as an ‘individual’. Has the loss of these shared design spaces affected the design world?

Hiromura It is not good or bad, but the ‘nature’ if communication is changing. It is becoming an activity and exchange based on what each person has connected, experienced and shared.

About the archive

ー I would like to ask you about your own archive.

Hiromura I have organised the posters and other materials that I used to store in an external warehouse and archived them in the office when I moved out of the office in 2021. The digitalisation of design has progressed and we don't need as much stuff as we used to. I have decided to keep one stock of posters at present, and we keep design drawings and materials for sign design in digital data, so we hardly need any space. Past works are grouped by project by age, while projects of current are organised and stored by each stuff. Both packaging and printed materials that had deteriorated or faded too much were disposed of when we moved. For the last 10 years or so, dedicated staff have been digitising.

ー What are your plans for the future?

Hiromura It is not easy to donate to universities and museums. Data, but the actual objects are difficult. I will organise as much as I can while I am still alive, but after that I don't know what will happen. But I think I am more organised than most designers.

ー Do you have any opinions on the design archive initiatives in the design world?

Hiromura That is necessary. When I go abroad, I envy design museums because they are so well organised. Ideally, we should also organise and data-code our works in preparation for that time. I also think that design organisations such as JAGDA and JIDA should take the lead in preserving valuable works. In any era, it is very important to know about past designs and the thoughts and activities of the designers who created them. I think archiving initiatives are important for this purpose.

ー Archive specialists, design historians and curators, insist that everything should be preserved for the future, but in practice it is difficult. In this context, I think it is essential for the designers themselves to make their own choices to some extent, but what do you think of the criteria for this?

Hiromura Ideally, the designers themselves and a third party with specialist knowledge should jointly make the decision.

ー What about your sketches or prototypes?

Hiromura In my case, I primarily work on sign, design related to CI and VI, and spatial design such as exhibitions, so I can preserve the work as digital data that has been photographed. Some people may have a lot of sketches and models, and it ultimately depends on how they judge a ‘design archive’.

ー There are many opinions about the design archive and it is an issue for the future.

Hiromura The Tokyo Midtown Design Hub recently organised an exhibition “Roots of Future: Exploring the Past to Discover the Future.” in collaboration with the ‘Japan Design Organisations as One(DOO)’ is a council of seven Japanese design organisations (space, interior, industrial, graphic, packaging, signs and jewellery) in Japan, which is involved in a variety of activities. The exhibition consisted of a ‘Chronicle’ section that looked at design from 1950 to the 2020s, and a ‘Discover’ section that explored the future of design through approximately 90 pieces selected according to themes from the design archive project undertaken by the council's ‘Japan Design Museum Establishment Research Committee’. The ‘Chronicle’ part was composed of a general view of design from the 1950s to the 2020s from the design archive project. By exploring Japanese design from multiple perspectives, the exhibition provided an opportunity to discover design in different eras and to consider design in relation to future life and society. I was asked by JAGDA to support them with the graphic design of the timeline and venue.

“Roots of Future: Exploring the Past to Discover the Future.” Hiromura was in charge of the main visuals and the exhibition graphics at the venue.

ー We at PLAT are also on friendly terms with DOO.

Hiromura DOO was founded in 1966, and in 1993, with the goal of establishing a design museum, it held valuable data after nearly 30 years of study groups. It is important to unify such projects with support at the national level. Therefore, it would be ideal to unify the data held individually by individuals, companies and organisations before creating a museum-like facility.

ー Not only DOO, but design museums are becoming increasingly active in design archiving. Collections of works and writings by the designers themselves are important archives. Thank you very much.

Enquiry:

Hiromura Design Office

http://www.hiromuradesign.com/