Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Motoko Ishii

Lighting Designer

Date: 22 June 2022, 13:30-15:30

Location: MOTOKO ISHII LIGHTING DESIGN

Interviewees: Motoko Ishii, Yoko Kanii (Managing Administator)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seiki, Aia Urakawa

Author: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Motoko Ishii

1938 Born in Tokyo

1962 Graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts

1965 - 1966 Moved to Europe and worked for a Finnish lighting manufacturer and a German lighting design company.

1968 Returns to Japan and establishes MOTOKO ISHII LIGHTING DESIGN

Honorary Member of the Illuminating Engineering Institute of Japan, Member of the Japan Lighting Manufacturers Association (JLMA), Fellow of the International Association of Lighting Designers (IALD), Member of the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES), Honorary Chairperson of Asian Lighting Designers' Association (ALDA), Honorary Director of Japan International Association of Lighting Designers (IALD Japan), Representative of Inter Light Forum

Description

Description

Motoko Ishii is a pioneer in the field of lighting design in Japan.

After graduating from Tokyo University of the Arts with a degree in product design, she worked for Q Designers, a company run by Riki Watanabe. During this time, she developed an interest in lighting design, and her subsequent experience studying luminaire design at a Finnish lighting manufacturer and architectural space lighting design at a German lighting design company formed the basis for her later work.

She returned to Japan in 1968, when there was still no field of lighting design in Japan, and her lighting designs were incorporated for the first time in Kiyonori Kikutake's "Hagi City Hall" and Kisho Kurokawa's "Space Capsule Akasaka" architectural spaces, and were regarded as a major newcomer Ishii is regarded as a major newcomer and has attracted much attention. In addition, as Japan did not have a culture of lighting up buildings, she began steadily spreading her work through the "Light-up Caravan", an independent project she started in 1978. Later, she began to work on lighting up various buildings, cultural assets and bridges, but she did not just illuminate buildings; she also adopted new technologies and original ideas to change the night landscape of Japan through light. She came up with an unprecedented production that used different colours of light depending on the season - cool white in summer and warm white in winter - to bring the Tokyo Tower, which had been buried in the darkness of the night, into vivid relief with light. The beautiful light moved people and the Tokyo Tower became a symbolic landmark of Tokyo. Now in her 80s, she is still actively involved in a wide range of work. In addition to lighting projects for large cities, lighting design for bridges and other civil engineering structures, lighting for cultural assets, lighting fixture design, light objects and performances, in recent years she has collaborated with her eldest daughter, lighting designer Akari-Lisa Ishii, on overseas projects. She also organises the "Light Culture Forum" and is committed to the inheritance and development of light culture at home and abroad. She has received various awards for her achievements over the years, including the Person of Cultural Merits award in 2019 and the Medal with Purple Ribbon in 2000.

We visited her office to ask Ishii about her work in lighting design, her thoughts on preserving archives for future generations and the design museum.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

(Domestic)

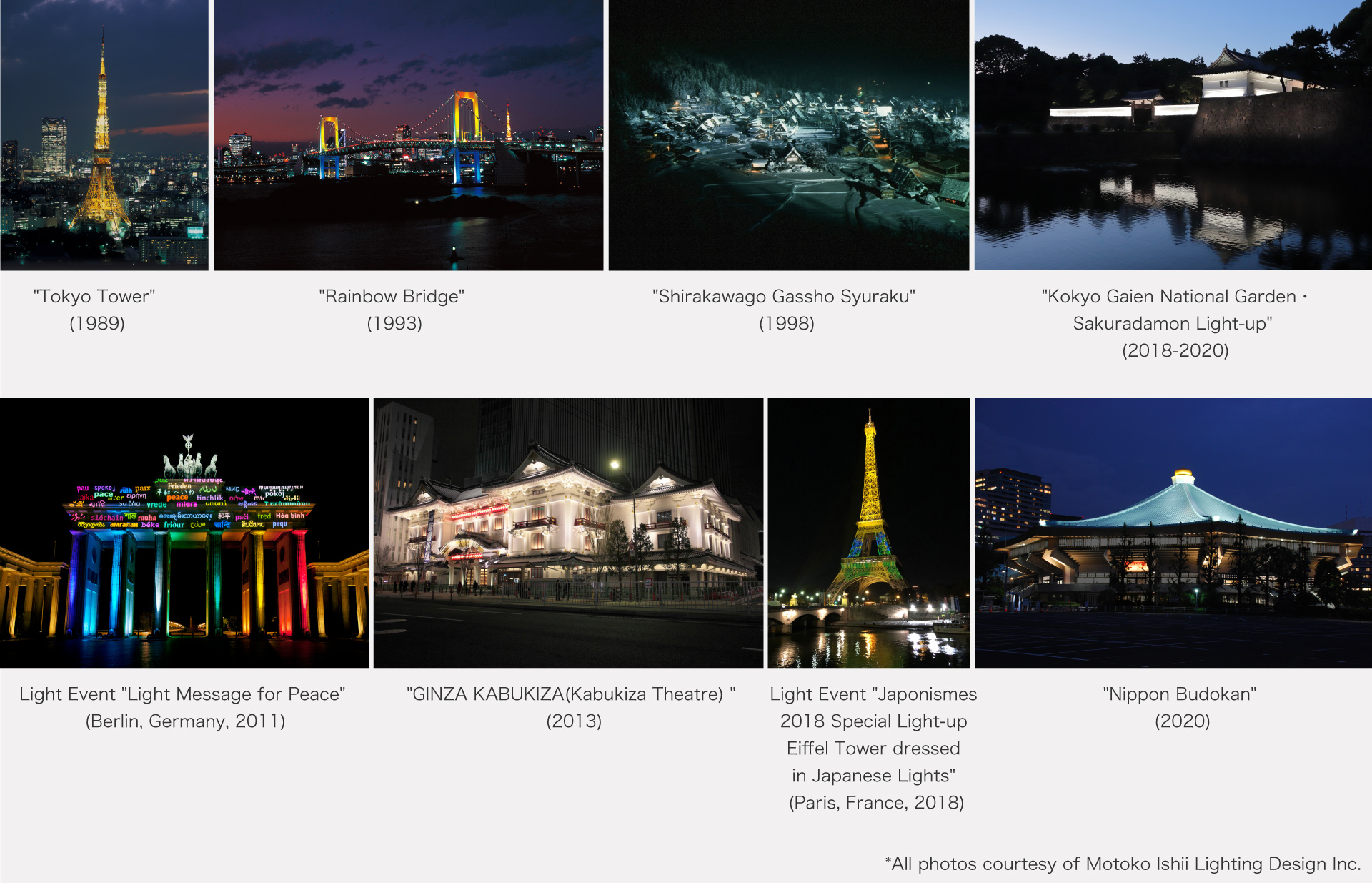

"Tokyo Tower" (1989); "Yokohama Bay Bridge" (1989); "Rainbow Bridge" (1993), "Shirakawago Gassho Syuraku" (1998); "Akashi Kaikyo Bridge" (1998); "Zenkoji Temple Olympic Colors Light-up" (2004-); Lighting projects in Kurashiki and Kagoshima (2006~2008); "Heijo-Kyo Light Up, Daigoku Palace" (2010); "Yomiuri Land Jewellumination" (2010-); "Tokyo Gate Bridge" (2012), "Soene Akari Park" (2012-); "GINZA KABUKIZA(Kabukiza Theatre) " (2013); "Kokyo Gaien National Garden" (2018/2020); "Sumida River Bridge Group" (2020); "Nippon Budokan" (2020)

(Overseas)

"Royal Reception Pavilion" (Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, 1981); "Shanghai World Financial Center" (Shanghai, 2008); Light Event "La Seine – Light Messages from Japan" (Paris, 2008)*; Light Event "Light Message for Peace" (Berlin, 2011)*; Light Event "Colosseum Light Messages" (Rome, 2016)*; Light Event "Japonismes 2018 Special Light-up Eiffel Tower dressed in Japanese Lights" (Paris, 2018)*

* Collaboration with Akari-Lisa Ishii

Products

"Space Crystal Series", YAMAGIWA (1970); "Space Jewelry Series", YAMAGIWA (1973); "THE Office Lighting System" OKAMURA (2009) etc.

Books

"MOTOKO ISHII MY WORLD OF LIGHTS", Libroport (1985); "LIGHT TO INFINITY", Libroport (1991); "CREATION OF LIGHTSCAPE", Libroport (1997); "LIGHTING HORIZONS", Rikuyosha (2001); "Utsukusii Akari o Motomete- Shin Ineiraisan", SHODENSHA (2008); "LIGHT+SPACE+TIME", Kyuryudo (2009); "LOVE THE LIGHT, LOVE THE LIFE", Tokyo Shimbun (2011); "MOTOKO∞LIGHTOPIA", Kyuryudo (2020)

Interview

Interview

I would be very happy if my archive could be preserved for future generations and be of use to young people

Encountering and learning from lighting design

Ishii I am very interested in and support the activities of this PLAT (Platform for Architectural Thinking) design archive, and I hope I can be of some help. I have been wondering what has happened to the items belonging to those who have passed away, and what is happening to Mr. Riki Watanabe's items now?

ー Mr. Riki Watanabe's family took the items he was attached to and METROCS has kept the drawings, furniture and photographs. In addition, Mr. Akira Yamamoto, a former staff member of Q Designers who supported her work in his later years, has acquired furniture and books from his home (see Riki Watanabe's page, interviewed in July 2017).

You worked part-time at Q Designers while you were a student at Tokyo University of the Arts, and after graduation you got a job, which is when you first encountered lighting design.

Ishii I was with Q Designers for about three years. At that time, design was in its infancy, so I did a lot of different jobs. I designed everything from small objects like ink bottles to large appliances like refrigerators, as well as graphics like logos, and I was taught all the basics of product design, including plaster models, prototypes and how to draw line diagrams.

At one point I was given the opportunity to design a lighting fixture, which was the starting point. When the prototype was finished and the light came on, I was very impressed. The books and cups on my desk were illuminated by the light, and their colours and shapes came into clear relief. This means that without light, we would not be able to see or understand anything. I thought how great light is. From there I became interested in light and lighting design and wanted to learn more about it.

I saw a design book called "Scandinavian Domestic Design" (Methuen, 1963) and sent a letter to Stockman-Orno Ab in Finland, which was published in the book, and the head of the design office, Ms. Lisa Johansson-Pape I received a reply from the head of the design office, Ms. Pape, saying that she would accept me as an assistant. I learnt a lot there, and what Ms. Pape said, "Light is not something to be seen, but something to be bathed in and felt", became my motto.

ー How was life in Finland at that time?

Ishii I was impressed by the cleanliness and the beauty of everything in Finland. When I went into a shop to buy some crockery, I found that all the crockery was sophisticated and in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art, New York. It was completely different from Japan at that time. In Japan, modern design was finally coming onto the market, but it was a time when things with floral patterns and designs were considered good, and plain white tableware was thought to be strange.

I think it was good for me to go to Finland when Japan was in such a situation. And in Japan at that time, women only had two choices: to be single and work for the rest of their lives, or to get married, quit work and become a full-time housewife. It was unthinkable for a woman to live alone, and when the husband was transferred, it was commonplace for the wife and children to accompany him to his new post.

At that time, 1965, there were women in the Finnish Cabinet, Stockman (Orno's parent company) had a number of women on its board, and there were nurseries for people with children. I was surprised to see how advanced the country was, with single people and married people all working naturally and as a matter of course.

The following year, I had the opportunity to work for Firma Lichit im Raum in Germany, which does lighting design for architectural spaces, but in Germany, many women are full-time housewives, which is similar to the situation in Japan. At Firma Lichit im Raum, the projects were large and the amount of work was enormous, so I worked hard from morning till night every day.

Working as a female designer

ー You established your office after returning from Europe in 1968. I don't think there were many women designers or freelance designers. You established a new genre of lighting design in Japan, and it must have been quite a struggle for you to be so successful in your work.

Ishii At the time, there was no field of lighting design in Japan, and when I spoke to various people, I was told that it would be impossible in Japan, such as where I would get my design fees from, or that such a position was impossible.

But I have never thought of myself as a woman who has worked hard or struggled. I have never thought that because I am a woman that it is difficult to do my job, or that because I am a woman I am losing or gaining, or because I am a man or because I am a woman. There are many things that make me angry when I work, but I think it's the same for men.

When I get a job, I do it honestly and properly. And if it goes well, the next job comes along and I do it well again, and I have been doing it with the belief that the only way is to build up trust with each project. I think the three most important things in gaining people's trust are being on time, keeping promises and achieving the best possible results within the budget. I am very careful with construction projects because they involve a lot of money.

ー You first started working in lighting design in Japan when you met five prominent architects through an introduction in an architectural magazine. When you met one of them, Mr. Kiyonori Kikutake, he showed you a model of the "Hagi City Hall" and asked you "What kind of lighting can you do for this space? " You immediately responded with three design proposals. Later, for "Tokyo Station", you came up with the idea of "a light that gently and softly envelopes, as if illuminating a famous actress of the past", and for "Shirakawago Gassho Syuraku" in Gifu Prefecture, you came up with "a light like gentle, faint moonlight". Light is a conceptual and abstract thing, so I think it is very difficult. How do you always come up with such light?

Ishii In my case, it is usually always intuition. As soon as I see a site, an idea pops into my head of what I want to do here. Sometimes I make sketches so I don't forget, but all the ideas are in my head.

I also work quickly. In architectural space projects, as soon as we start, we are in a battle for position. If I want to put a chandelier in the middle of the ceiling, they say there's an air-conditioning vent there or a sprinkler system, so I'm always the first to decide on the design and hold the place where the light will look most beautiful.

ー You have the idea in your head, but for large-scale projects involving many people, such as "Rainbow Bridge" or "Japonismes 2018 Special Light-up Eiffel Tower dressed in Japanese Lights", how do you explain the idea to your collaborators?

Ishii In the case of large projects, we make a lot of drawings, models and prototypes to explain the project. However, light is something that cannot be understood without seeing the actual thing, so it is essential to conduct experiments beforehand, using illuminance calculations as a guide only. We conduct experiments in studios at different locations from the office, as well as on site. For bridge projects, I do things like taking a boat ride to see the site.

Whenever I am approached about a project, I always go into it thinking that I want to try "something new". For the "Yokohama Bay Bridge" project, I not only tried to make the white bridge float with light, but also to dye the top of the main tower blue for 10 minutes every 30 minutes to symbolise the colours of the city of Yokohama. The "Rainbow Bridge" was the first bridge in the world to partially incorporate photovoltaics in its lighting design.

So I am always on the lookout for new technologies. Whenever I see or hear about something in the newspapers or on TV, I immediately contact the manufacturer to show it to me, or I am approached by them to sell it to me. There are a lot of large lighting trade fairs in Europe and elsewhere, so that's where I find out about them.

Sometimes we try out new technologies in our projects, or if we want to create this kind of light, we develop new technologies to create it. For the "Eiffel Tower" project, we wanted to colour the brown tower gold, like a golden folding screen, so we consulted a Japanese manufacturer and together we developed a floodlight that emits a golden light, projecting Korin Ogata's National Treasure Irises Screens onto the golden-tinted tower. About 120 floodlights were transported to Paris from Japan.

Creating new value through light

ー In 1978, you started the "Light-up Caravan", an independent project to illuminate buildings in various locations, on your own initiative, while the culture of lighting up buildings and the term "light-up" had not yet existed in Japan. This is a wonderful activity that has made a great effort to promote lighting design.

Ishii The initial impetus for the "Light-up Caravan" was the decision to hold the International Congress of Illuminating Engineers in Kyoto in 1978. I was astonished to see the city of Kyoto at night because I had seen the wonderful urban landscape lighting in London, the previous host city. At that time, Japanese cities had only three ways of lighting: street lighting, streetlights in shopping streets and neon signs on pachinko parlours and bar signs, and Kyoto was no different at night, with all the wonderful cultural assets shrouded in darkness.

So I created a lighting plan for the city of Kyoto on my own and approached the Kyoto City Hall. I was still young and there were only one or two people in the office. I visited the city hall without any introduction and tried my best to explain the plan, saying, "I'm from Tokyo, I made the Kyoto Landscape Lighting Plan, please have a look at it, and I think we should do it". In the end, they didn't take me up on it, so I chose Nijo Castle and Heian Shrine and decided to do it as an independent project, using my own money to rent a power supply vehicle and procure equipment.

ー Then you went on to light up typical buildings and cultural assets all over Japan: Sapporo, Sendai, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Hiroshima and Kumamoto. It wasn't until 1986, eight years later, when the city of Yokohama asked you to light up the city for an event, that it led to an actual project. Did you ever give up along the way?

Ishii No, it was interesting and fun for me. When I illuminated a building with lighting, I was impressed by myself, "Oh, it's so beautiful!" I was always excited thinking about what to light next. That's when I realised that I was lucky to have gone to Tokyo University of the Arts. Sculpture students had to pay for materials, as well as for transporting their work to exhibitions and returning works after they were unsuccessful, while oil painting students had to buy cheap browns as much as possible, as beautifully coloured paints were expensive. Some people didn't have money and ate white rice with sauce in the school cafeteria. I saw those people, so I thought that if I wanted to do it, I would have to pay for it myself, and I was happy to go to the administration office to ask for permission to light up that building, or to go to the fire station, police station or police box to say hello.

ー Even when architects created wonderful buildings in cities, at night they were buried in darkness. You have shown the possibilities of new architecture and urban design by bringing them to light and bringing them to life, and by bringing excitement to them through light.

Ishii My theory is that daytime sunlight shines from above, but landscape lighting shines from below, so we can see things that we cannot see during the day, and that is where new value is created. When I give lectures, I often say that the Earth we live on has 24 hours a day. Half of the planet is daytime and the other 12 hours are nighttime. We have not used the night time as an object of design until now. We are going to explore this time.

"Nippon Budokan" was also dark at night until then, even though it hosted so many rock concerts. When the building was extended and renovated, plans were made to light up the exterior, and we were told about it. Fuji, and as a martial arts hall of fame and a sacred place for transmitting culture, I came up with the idea of "a quiet, pure light like the light of a full moon on the sacred mountain Fuji". The roof's tile rods (Shingi) were each fitted with a small LED floodlight, which emitted light as if the entire main roof were a mountain. It is actually an amazing technology to make such a small lighting fixture emit so much light. The technology at this time was also newly developed, and we conducted a number of experiments on the number and arrangement of the floodlights, some of which were carried out in advance.

Gentle light like moonlight

ー I've heard that light-ups abroad are often dramatically and strongly crisp, whereas yours is characterised by a quiet, gentle light.

Ishii I don't like the contrast between light and dark very much, and I prefer night scenes with gentle light, such as the light of a full moon. That's what I'm aiming for. I think the light of a full moon is a light environment that the Japanese have loved since ancient times.

The "Kokyo Gaien National Garden" was also conceived around the theme of moonlight. Although it is in the heart of the city, this is the only place in the city that is shrouded in darkness at night, so I had wanted to illuminate it for a long time. We came up with the idea of a Japanese-style lighting scheme, incorporating the world's first attempt at fence lighting, in which two types of LED light sources with special lenses are built into the lawn fence, so that the light quietly illuminates your feet and you can enjoy the moonlight pouring down from overhead.

ー There has always been a culture of moon-loving in Japan, as seen in the Katsura Imperial Villa and Ginkakuji Temple. Is such Japanese culture the origin of your idea of light?

Ishii Actually, I was never really interested in Japan. It was after the war, when American culture had entered the country, when I became aware of things, so I didn't want to put myself in the Japanese thing.

However, one day my daughter suddenly said she wanted to do lighting design, and after a trip to Paris she said to me: "Your designs are very Japanese, Mum". I was surprised. And she said, "You think it's nice to have moonlight over the whole place, not a clear division between light and dark, don't you?". I had never thought of it that way myself, but when she said it, I realised she was right. That was when I was in my 60s.

ー You and your eldest daughter Ms. Akari-Lisa Ishii have collaborated on a number of projects, including "Colosseum Light Messages" and "Japonismes 2018 Special Light-up Eiffel Tower dressed in Japanese Lights". Does Ms. Akari work as the Paris office of your agency?

Ishii No, she has her own company and we collaborate on each project when I work abroad. She graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts, the same university as me, and went on to postgraduate studies at The University of Tokyo, during which she studied at a design school in Paris. After returning to Japan, she joined my office as a staff member, and after three years, she said, "It's time for me to go and train as a warrior" and joined a lighting design office in Paris, where she was selected as chief after about two years. She then set up her own company, I.C.O.N., in Paris in 2004.

I was worried about how she would find work in Paris, where she has no geographical or blood ties, but she is now one of the five leading mid-career lighting designers in France and has been elected to the board of the French Association of Lighting Designers. She works not only in Europe, but also in the USA, the Middle East and Japan. I actually think how much easier it would be for me if she were in Japan, but she works hard and enjoys it, so I am happy for her. I get on very well with her and we have never had a fight. She may be reserved with me, though, or perhaps she is afraid to offend me.

ー Among all the projects you have done around the world, is there a light or lighting design in your life that has left a lasting impression on you?

Ishii The most beautiful and beautiful light is, after all, natural light. The sea of clouds illuminated by a full moon that I saw on the way back from Guam by plane, the Northern Lights in Lapland, which are so spectacular that even the locals don't get to see them very often, the big sunset on the Big Island of Hawaii, the full moon shining like a komorebi in the garden of a villa in Karuizawa in winter. Then, when I went to Lake Biwa for some filming, I saw the lake's surface turn pink at sunset. I wondered what kind of phenomenon caused the lake to turn pink like that. That kind of natural light is incomparably beautiful. It is not a direct source of inspiration for my work, but it is a good experience for me to see various kinds of beautiful light.

I believe that there are still many unexplored aspects of lighting design. At MAISON & OBJET this September, I will be presenting a kind of solar-powered dress that I made with my daughter. It generates electricity from the sun and uses the stored energy to charge your mobile phone.

The material is compiled with reference to German companies

ー From here I would like to talk to you about your archive. I understand that you have numbered your projects in serial numbers, in reference to what used to be done at Firma Lichit im Raum in Germany, where you used to work.

Ishii At Firma Lichit im Raum, drawings and projects were numbered consecutively, with the date and the name of the person who wrote them, and related documents were filed together and neatly arranged on shelves. This was so that if someone was on leave or quit, another person could smoothly take over the work. I thought it was a very good system and I have been filing drawings and documents in the same way since 1968, when I set up my office. I also keep a project number, which is now around 2000. I also keep a record of the contents of our meetings. I adopted this system based on what the American architect Mr. Minoru Yamasaki used to do in his office when I often worked on lighting design for his architectural spaces in the 1970s. The staff in the general affairs department work very hard to organise and manage those materials, and they are very helpful.

ー Aside from those project files, ledgers and records of meetings, what else do you keep as documentation?

Ishii There are more drawings, publications, photographs and, more recently, videos. It is a great pity, but I have generally disposed of prototypes as they take up a lot of space. I also make a lot of models, including full-scale and 1/100 scale models, but now I think about it, it's a waste, but I've thrown most of those away too. I have kept the models that I liked, though.

ー Do you keep hand-drawn sketches?

Ishii Most of the time, I don't keep them. If I think something should be kept, I put it in a box without writing the date on it. I don't think it's worth keeping sketches and other things that are in progress, and I think that when a project is finished, the only thing that will remain are photographs.

Kanii Other items stored include videos of Ms. Ishii's TV appearances and audio data from the radio. We convert photos to data and have VHS videos converted to DVDs, and we always try to budget for such work and set a time frame for it. The materials are stored in two rooms on the ground floor of this office and on the fourth floor, with others stored in Ishii's Karuizawa villa and in an external warehouse.

ー You regularly publish collections of your work and have written many books, and in 2020 you published a collection of your work entitled "MOTOKO∞LIGHTOPIA", which covers 50 years of your career. I think that these collections of works and books can also be considered as an archive. Do you have a desire to preserve them as archive material for future generations?

Ishii Every two years we compile our projects in the booklet "LIGHTING SENSOR" (Published by LIGHTING SENSOR), and when we have accumulated a certain amount of work, we publish it in a book. Of course, there are publishers who accept our projects, so we publish them, but thankfully, "MOTOKO∞LIGHTOPIA" seems to be selling so well that the publishers have almost no stock left.

I don't want to keep them as an archive, but rather to give young people who want to become lighting designers an idea of what I used to do. In some respects I don't know what will happen to lighting design in the future, but if I can preserve it for future generations, I would be very grateful, and if I can give young people something to refer to, I will be very happy. If there is anyone who is interested in such a movement, I would like to support them and I would encourage them to do it.

ー In most design offices, I think they are too busy with their day-to-day work. But I think it's wonderful that you not only carry out projects, but also organise and archive materials, and proactively carry out activities that lead to the future, such as educational activities to promote the culture of lighting design.

Ishii Thank you very much. I am very happy to hear you say so.

ー A final question: what are your thoughts on the current situation in Japan, where there are almost no design museums archiving designers' materials?

Ishii I think the activities of the PLAT members are wonderful. However, I think that the national government should be responsible for these activities. Just as I used the name "Landscape Lighting Study Group" when I organised the "Light-up Caravan", why don't you create, for example, the "Secretariat of the Preparatory Committee for the Establishment of the Japan Design Museum" and tell the government how wonderful Japanese design is and what would happen if they don't do something like this now? Why don't you encourage the government to do something about it? First of all, you need to clarify the definition and purpose of the Japanese Design Archive and estimate the necessary costs. You are all young, so please do your best - people in their 60s and 70s are still in their prime. I'll be happy to help you.

ー Thank you very much for your very useful advice on the enhancement and continuation of our project. We will refer to it and do our best. Thank you very much for your time today.

Enquiry:

MOTOKO ISHII LIGHTING DESIGN

https://www.motoko-ishii.co.jp