Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Hiroshi Kashiwagi

Design Critic

Interview: October 21, 2024 13:30-15:30

Location: Kashiwagi Residence

Interviewees: Mikiko Kashiwagi, Mana Uchiyama

Interviewer: Yasuko Seki

Auther: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Hiroshi Kashiwagi

Design Critic

1946 Born in Hyogo Prefecture

1970 Graduated from Musashino Art University, Department of Industrial Design

1983 Assistant Professor at Tokyo Zokei University

1993 Professor at Tokyo Zokei University

1994 Awarded the Katsumi Masaru Prize

1996 Professor at Musashino Art University (-2017)

2021 Passed away

Member of the Art Selection Committee of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, Professor Emeritus of Musashino Art University, Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Art (RCA), Member of the Jury for Media Arts of the Agency for Cultural Affairs, etc.

Description

Description

The three decades from the 1980s onwards, when Hiroshi Kashiwagi was active as a design critic, was a time when Japanese society matured and concepts such as design, lifestyle and culture became widespread. Design became an important factor as people, who were now well supplied with food, clothing and housing, sought better products, better-looking design and richer lifestyles. Kashiwagi experienced this shift in the times through the city surveys he worked on for many years. It means that people have come to pay more attention to the image (the term ‘added value’ was often used at the time) that things give off, rather than to their function or convenience. In his book “Industrial Design Thought in Modern Japan”, he stated that differences in the form of things are differences in images, and that we were surrounded by a flood of images. This sentence also foreshadows a digital society inundated with images.

Kashiwagi is recognised as a design critic, but he was a civilisation critic wearing the glasses of design.Therefore, he could talk about design from all areas and consider design in all areas. With the spread of social networking and the internet, everyone has become a critic and commentator, and all values have become relative, so that critics are becoming less present in the worlds of art, film, literature, architecture and design as they once were. In this sense, Hiroshi Kashiwagi may have been the last critic who could talk about design from a civilisational perspective. That is why the many books and design critiques left behind by Kashiwagi carry even more weight in an age without critiques. It is a pleasure that many of these materials are now archived at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka.

In this issue, we interviewed his wife Mikiko Kashiwagi and daughter Mana about Hiroshi Kashiwagi's activities, personality and archive, and received text from Toshino Iguchi, head of the Design History Research Centre Tokyo, a non-profit organisation that helped establish his archive.

Masterpiece

Main publications (co-authored)

“Industrial Design Thought in Modern Japan”, Shobunsha (1979)

“The Myth of Toys: Aspects of Modern Toys”, Mainichi Shimbunsha (1981)

“The Design Thought of Daily Necessities”, Shobunsha (1984)

“The Iconography of Desire”, Miraisha (1986)

“The Power in the Portrait”, Heibonsha (1987)

“Design Strategy”, Kodansha Gendai Shinsho (1987)

“The Politics of Tools and Media”, Miraisha (1989)

“The 20th Century of Design”, NHK Books (1992)

“The Politics of Housework”, Iwanami Shoten (first published by Seidosha) (1995)

“Gendai Design Jiten (Dictionary of Contemporary Design)”, Heibonsha (1996),

co-edited by Junji Ito.

“The 20th Century of Fashion: Cities, Consumption and Sex”, NHK Books(1998)

“Hints of Colour”, Heibonsha Shinsho (2000)

“Building houses: Design historians and architects”, Iwanami Shoten (2001)”,

co-authored by Yoshifumi Nakamura.

“How Was the 20th Century Designed?”, Shobunsya(2002)

“Modern Design Criticism”, Iwanami Shoten (2002)

“The Cultural Theory of ‘Shikiri’”, Kodansha (2004)

“Ganbutu-Zoshi’ “, Heibonsha Corona Books (2008)

“Textbook of Design”, Kodansha Gendai-Shinsho (2011)

“The Room of the Master of Literary Legend: Reading from Diaries”, Hakusuisha (2014)

“The Life Force of Vision: The Restoration of Images”, Iwanami Shoten (2017)

Selected exhibitions (supervise)

‘Japanese Avant-garde Art 1910-1970' ,Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, The Japan Foundation (1986)

‘Ikko Tanaka : A Retrospective', Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (2003)

‘People and Robots: The Cybernetic fantasies ', Maison de la Culture du Japon à Paris (2003-04)

‘Japan Design Today 100’ ,The Japan Foundation (2004-2014)

‘WA: Contemporary Japanese Design and the Spirit of Harmony', Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris, Japan Foundation (2008)

‘Design in Musavi: Tracing Design through Collections and Education’, Musashino Art University Museum & Library (2011)

‘Design at Musavi II: Design Archives from 50s to70s’ 〃 (2012)

‘Rabbit Smash Exhibition’, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, co-curated with Yuko Hasegawa (2013)

‘Graphic Design ‘Persona Exhibition’, DNP Art Communications (2014)

‘Dreaming of Modern Living – The Industrial Arts Institute’s Activities’, Musashino Art University Museum and Library (2017)

Interview

Part 1

Interview

The knowledge and relationships he gained there

formed the basis for Kashiwagi's subsequent design criticism.

How the Kashiwagi Archive was created

ー Today, we would like to ask you about Hiroshi Kashiwagi's archive and his life from the perspective of his family.

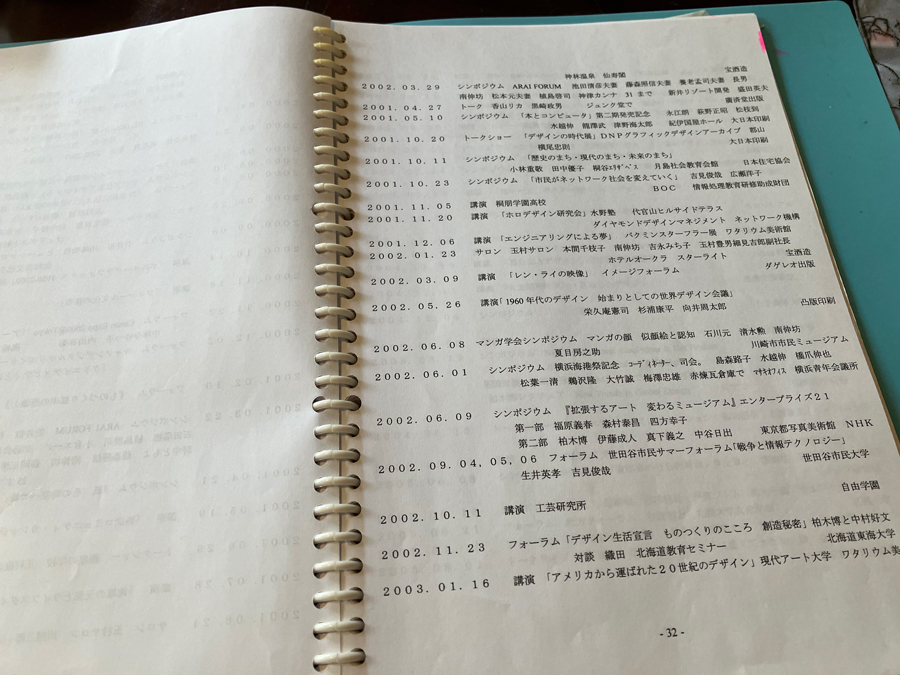

Kashiwagi The first thing I did after Kashiwagi passed away was to produce a catalogue of his activities and donate his vast collection of books. The catalogue of his activities was written down in chronological order according to several items, such as books (co-authored), magazine manuscripts, lectures, exhibitions, TV appearances, competition jury members, etc. I sorted his notes, documents, newspaper clippings and photographs according to the list and stored them in files and boxes. Last year, with the help of design historian Toshino Iguchi, we donated some of these items to the Nakanoshima Art Museum, Osaka (hereafter NAKKA).

Catalogue of Mr Kashiwagi's activities being compiled by Mrs Mikiko.

ー Can you tell us how the donation to NAKKA came about?

Kashiwagi I wanted to put together a huge collection of books somewhere and donate

them. I consulted with the university library through Professor Kyoji Maeda of Musashino Art University (hereafter Musabi). I waited for a year and a half, but it was not possible. I then explored the possibilities with other institutions, but all were unsuccessful.

It was then that Ms Iguchi decided to help us and contacted NAKKA. Tomio Sugaya, the

director of NAKKA, came to our house to look at his collection and materials and said, ‘For

us, the notes, drafts and materials that Kashiwagi used to write his books are more valuable

than the books in our collection. I was very surprised

to hear this, because I had always thought that the books had more value than Kashiwagi's notes and scraps .Then I am grateful that NAKKA is taking these things back.

ー And then you organised them for donation?

Kashiwagi First, Ms Iguchi picked out from Kashiwagi's bookshelves what was suitable for NAKKA from an expert's point of view, and we roughly sorted and sent in about 50 card boar boxes. Without her support, NAKKA would not have been connected and I would not have been able to judge the value of the materials, for which I am grateful. I recently heard that Kashiwagi archive information has been uploaded as a special collection on the NAKKA website.

※ See Nakanoshima Museum of Art. Osaka website

https://nakka-art.jp/

ー NAKKA has always been a museum that focuses on archiving, so it was really good to have the Kashiwagi Archive in the museum. What happened to the vast collection of books?

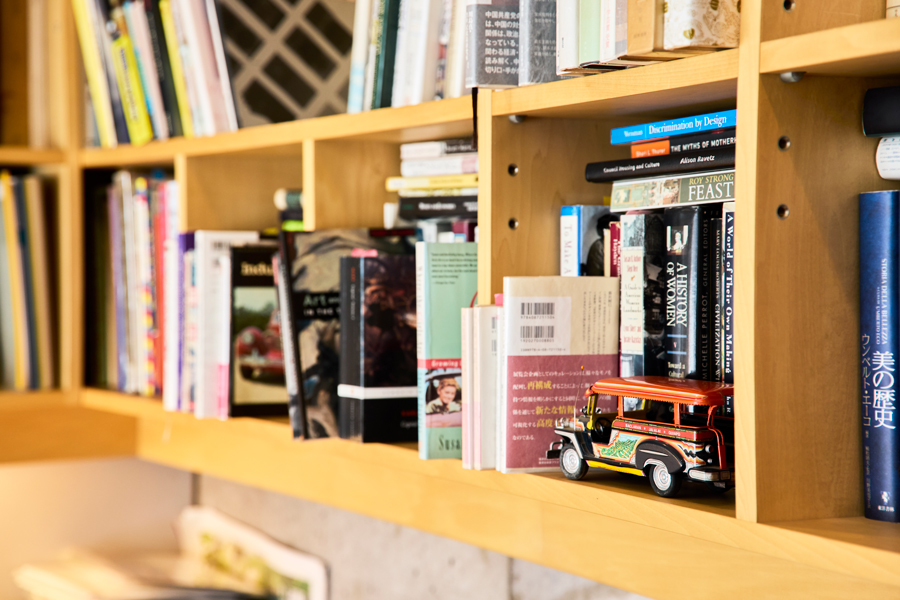

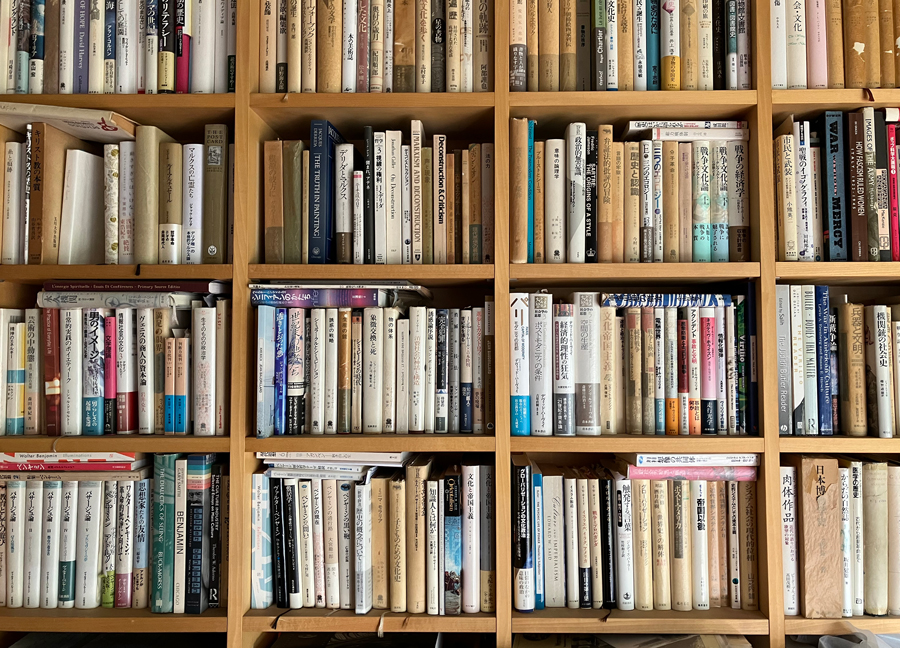

Kashiwagi I had one particular wish for the donation of the books in the collection. That is that I wanted to treat the books as they were arranged on the shelves. The way books are arranged reflects the thoughts in a Kashiwagi's brain, so I think the value of the collection would diminish if the books were to fall apart. And the Mousavi library took some dozens of rare and valuable books, for example, the magazine “FRONT”, which was published during the war, and books on commercial design from the early Showa period.

ー “FRONT” was a propaganda magazine for foreign countries that was art-directed by Hiromu Hara. Did Mr Kashiwagi have a collection of such rare books?

Kashiwagi The purchase of ”FRONT” was accidental. Kashiwagi loved books and bought them from various routes, including second-hand bookshops in Jimbo-cho and book salesmen who came to his university laboratory.

ー I understand that you are continuing to organise the vast amount of material you have, but what about the future?

Kashiwagi There is still a miscellaneous amount of material left at home, which is being organised. I also have scrapbooks and files. In the scrapbooks, clippings from magazines and newspapers are pasted without any context, and I don't understand them at all, but they must have been articles that had some meaning for him.

There is a huge amount of material at work, which is being sorted out.

The road to becoming a design critic

ー Do you know how Kashiwagi became interested in design criticism?

Kashiwagi After graduating from university, he taught at Ochanomizu College of Art and Asagaya College of Art, worked as a magazine editor and surveyed the city. It was a time when the student movement had a strong influence, and it was popular to actually go out and survey the streets, and people who are now active in the worlds of literature, architecture and criticism formed groups to carry out such activities.

For example, Iwao Matsuyama created ‘Konpeito’, Riichi Miyake, Shuji Nuno and others created ‘Hinageshi’, and Makoto Otake and Tomoharu Makabe created groups such as the ‘Institute of Remains’. Terunobu Fujimori and Genpei Akasegawa's “Street Observation Society” was about signboard architecture and Akasegawa's “Tomasson” is well known. Kashiwagi also formed a group called ‘Sokkosyo(Weather Station)’ with Ryuichi Kawamura and others, and went out to Yokohama, Fussa and Hachioji to take photographs of things of interest. I also joined this group and worked with them. I heard that Kashiwagi was applying the surveys' methods to classes at Ochanomizu and Asabi, and that the way he proceeded in what is now called a workshop style was popular with the students. I believe that the activities of the time, the knowledge and relationships he gained there formed the basis for Kashiwagi's subsequent design criticism.

ー I understand that you were also with him in Surveys, what was it like?

Kashiwagi I was close to him and was impressed by his unique perspective. Even when he was looking at the same thing or scenery, he was taking pictures and thinking about things that ordinary people would never think of. The method of Surveys suited his relentless intellectual appetite, and the knowledge and data he gained through his practice and experience became the core of his design criticism.

ー In his twenties, Mr Kashiwagi used the survey method to research cities, lifestyles and social phenomena, and to study customs and public opinion. What do you think is the background to the shift of such perspectives to design, tools, cities and information?

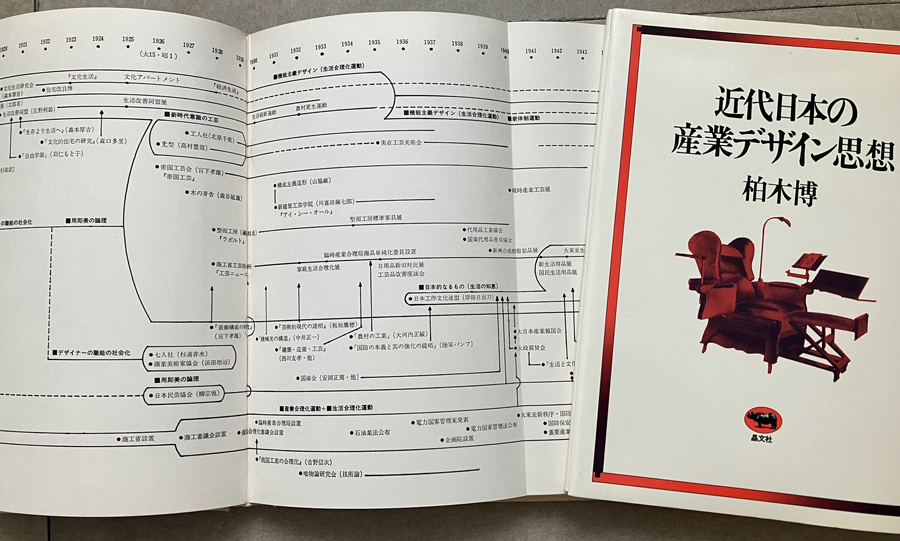

Kashiwagi I don't know the details, but the first book he published in 1979 was ”Industrial Design Thought in Modern Japan”. It summarised Japan's modernisation and design from the Meiji period to the post-war period in the context of industry, and was well received because there had been no such book in the past. In addition to the text, he compiled the chronology, index of people and other data, and all the illustrations in the text by himself. Kashiwagi's interest was not in good design or designer theory, but a broader cultural, semiotic or social perspective.

A diagram compiled by Kashiwagi. It is a first-class resource.

ー In the author's introduction to the book, he says that he is ‘exploring ways to reconsider the things we use unconsciously in our daily lives’, and I thought, ‘I see’.

Kashiwagi He is particular about the word ‘image’ and says that things should be thought of not only from the perspective of their usefulness, but also from the perspective of their ‘image’.

ー Mr Kashiwagi is known as a design critic, and Ms Iguchi said that it is important that Kashiwagi sees design as a theory of civilisation. Also, Seigo Matsuoka, a giant of knowledge, wrote on his website that ‘Hiroshi Kashiwagi has a radical critical spirit towards the major trends that are considered to be the progress of design’.

Kashiwagi He has published 37 books in his lifetime, and while they are centred on design, the thematic settings are very diverse.

ー Really, in the catalogue that Mikiko is compiling, his themes of the books cover all fields, from domestic science and housing, architecture and cities, graphics and tools, images and images, to toys, and the interlocutors for lectures and TV programmes are designers, aesthetics, literature, architecture, theatre and all kinds of researchers and experts. The breadth and depth of Kashiwagi's knowledge and interests is evident.

The housing and lifestyle of Hiroshi Kashiwagi

ー Kashiwagi, after publishing ”Industrial Design Thought in Modern Japan”, he took up a position at Tokyo Zokei University.

Kashiwagi He became an associate professor at the university in 1983, a professor in 1993 and was invited by Musabi to become a professor in 1996. Musabi was his alma mater, and because he was a postgraduate professor, he was not busy with classes and was able to devote his time to the research and writing he wanted to do. He was in charge of design history at the university, but as soon as he finished his business, he went home and did research and writing.

ー Mr Kashiwagi has also published a book about his house, which shows how much he loved his house. Were you particular about your residence and the way you lived there?

Kashiwagi We moved into this house in 2000. We asked Yoshifumi Nakamura to design our current house and left the design to him. Kashiwagi's commitment to his home was not half-baked, and I think he was blissfully happy to have built this house and secured his favourite place to spend time reading books, preparing documents and writing.

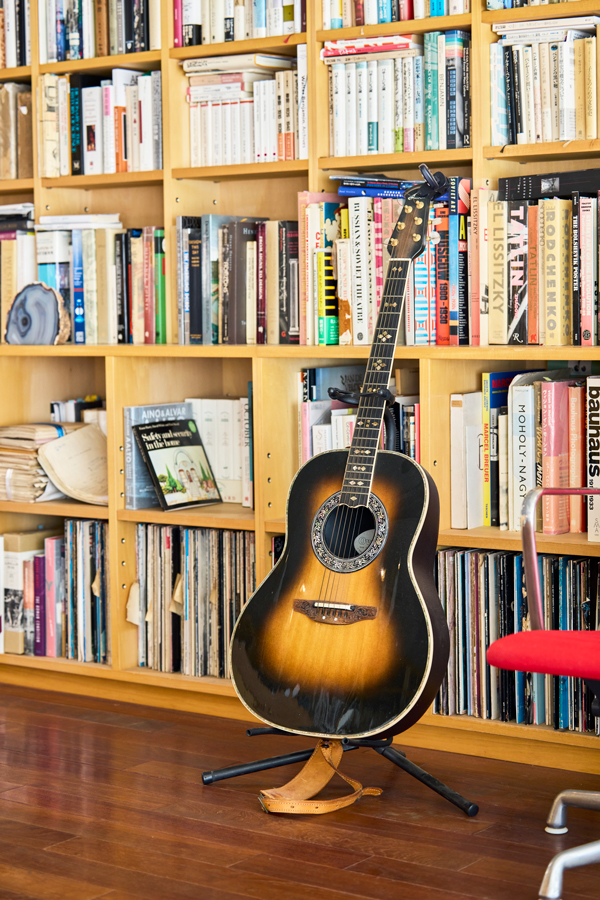

Kashiwagi's workplace and his vast collection of books, documents, etc. Photos: Yuki Akaba.

ー What kind of person was Mr Kashiwagi in general, and what kind of lifestyle did he lead?

Kashiwagi He was kind, serious and very studious. Usually, after dinner, he would go into his study to do research or write manuscripts. His research was not done on the internet, but mainly in printed form, such as books.He was quick to switch between family time and work, and was a person who was able to make a clear distinction between the two. He travelled a lot, including overseas, and was often away from home, but he rarely went out drinking with friends. During busy periods, he would use certain coffee shops in front of Kunitachi Station, Shibuya and Shinjuku as his office, and would hold several meetings and interviews at once.

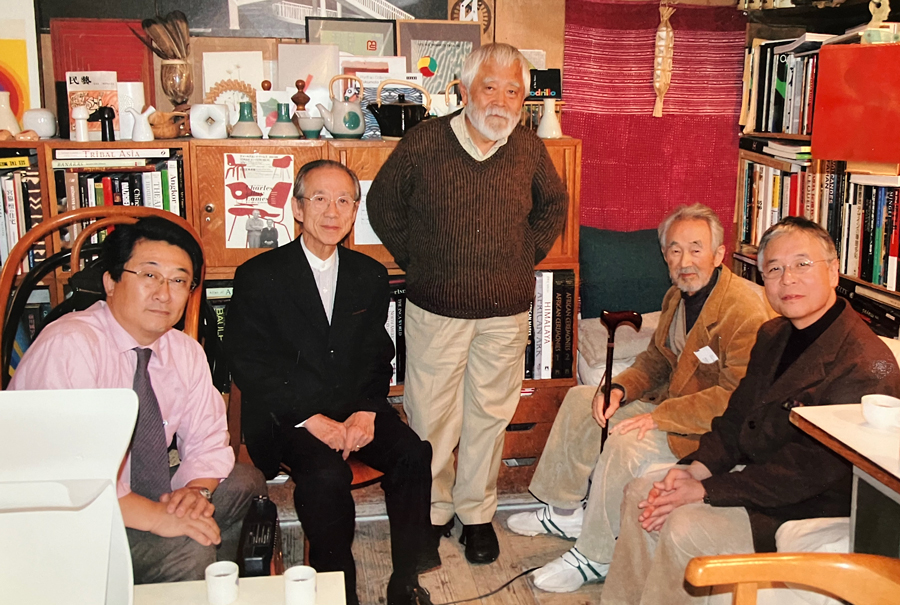

Mr Kashiwagi (far right) and Mr Sori Yanagi (next to him) at a meeting in Yanagi's office.

ー I also had meetings with Kashiwagi twice at a coffee shop in Shinjuku. He was a workaholic, but what were his hobbies?

Uchiyama From my point of view, I think he liked the values of living modestly and living life in the style of the novelist Fumi Koda. He also liked cute things and used to pick up pebbles and pine cones on his walks and display them. There was a time when he collected pin badges, and perhaps because of his job, he also collected camera loupes.

Kashiwagi We still have a blues guitar at his workplace, and when he grew older he also started kintsugi (metal-joining) and went to classes with his friends.

Uchiyama Kintsugi is expensive in terms of materials, and sometimes it costs more than broken vessels.......

Bookcase displays small items.

Kashiwagi By the way, Kashiwagi designed his own New Year's greeting cards.

ー Is this printing block his own work?

Kashiwagi Yes. He used to work as a magazine editor and was good at making block prints and instructions. He designed New Year's cards by himself, made the block prints and ordered them to the printing company, but the people in charge these days did not know the old way of submitting the block prints and it seemed to take them a lot of time and effort.

Uchiyama Why did my father go to the trouble of doing such time-consuming work when he had a PC at home?

Kashiwagi Maybe he was nostalgic about making New Year's cards the old-fashioned way - before PCs became popular, he used Itoya's rather good manuscript paper, and when the manuscript was finished, I copied it at a copy shop and sent it to the publisher by registered post. Then word processors and PCs took over, and he could send manuscripts by email.

The instructions were drafted on Itoya’s manuscript paper before the instructions were compiled.

ー He has properly specified the typeface, grade and even the colour in the instructions. Did he do everything himself?

Kashiwagi Yes. He made all the PowerPoint presentations he used in classes and lectures himself. He used to work part-time as an editor, so he also finished the layouts beautifully.

ー We had a lot of fun talking about the instructions for the New Year's cards (laughs).

Talking about design from a civilised perspective.

ー In Mr Kashiwagi’slater years, he also wrote from a unique approach that links literature and space.

Kashiwagi When he was over 60, he began to compile manuscripts from such perspectives as how literature describes houses, what kind of houses literary figures lived in, or imagining interiors from their writings. He was interested in the theme of good design and how ordinary people incorporated design into their lives.

ー He has written many books on the themes of home economics, living and housing.

Kashiwagi Rather than pursuing a single theme, his interests shifted in various ways, he studied and compiled them into books. He never stayed in the same place. The theme of ‘shikiri’ was stimulated by his interaction with the Living Design Centre in Shinjuku.

ー Kashiwagi's design critiques include ‘humanism’. Recently, design is often discussed from the perspective of economics and science and technology, but Kashiwagi has never wavered from his perspective of human-centred design.

Kashiwagi In that sense, I would be happy if we could continue to organise Kashiwagi's materials and preserve the collection in a better form.

ー Kashiwagi's materials are very difficult to organise, but I think we are very lucky to have an archive at NAKKA. Thank you very much for your time today.

Part 2

Ms Toshino Iguchi, President of the NPO Design History Research Centre Tokyo, who worked hard on the ‘Hiroshi Kashiwagi Archive’ at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka(NAKKA), compiled this article from the perspective of a design historian, answering PLAT's questions about the background to the creation of the Kashiwagi Archive and the design archive.

About the Hiroshi Kashiwagi archive

Text: Toshino Iguchi

The reason for organising Kashiwagi's Archive

After Hiroshi Kashiwagi passed away on 13 December 2021, I was unable to accept the news for some time. Mr Kashiwagi had recovered from a serious illness several years ago and was completely healthy, so I think I was quite upset myself when I heard the news of his passing. A little later, I sent a letter of condolence to Mrs Mikiko and visited her home with a friend who had helped him during his lifetime, which was the inspiration for the idea of creating the archive.

There were numerous precious books and documents remaining in the study and on the bookshelves. Mrs Mikiko wanted to donate them to the library of Musashino Art University, where Mr Kashiwagi worked, but the university has a rule that it will not accept donations of books from retired teachers' collections, so she was looking for a place for the precious books to go.

History of the donation to NAKKA and details of the donation

As a reflection of Mr Kashiwagi's diverse work, his study contained books in the field of design studies, such as woodwork, crafts, advertising, housing and architecture. In addition, there were books on art theory, art criticism, materials related to domestic science, children's literature and books of thought by Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno, Jean Baudrillard and others, showing that his field of study was wide-ranging. In addition, there were ”Imperial Industrial Arts”, ”Kogei News”, ”Commercial Art Complete Works”, and ”Kōkōkai”, which are indispensable for the study of modern art and design, as well as original materials that were not reprints of ”Shashin Shuho” and ”Iwanami Shashin”. There was also valuable material” such as the Russian Constructivist architect Yakov Chernikhov's ”Fantasy Architecture 101” (1933) and the British 19th-century satirical cartoon magazine ”Punch”.

When I visited Kashiwagi's study room, I felt that these rare books and the related materials he collected for his writings needed a place where they would not be scattered and where they could be stored in one place and made available to future generations of researchers. Mr Kashiwagi was involved in various aspects of Japanese design activity, and we felt that his material would also shape the history of design in Japan. Books are available in libraries and may be obtained from second-hand bookshops. However, there are no other records of the domestic and international projects (exhibitions, projects, etc.) in which Mr Kashiwagi was involved, and it is possible to uncover the history of Japanese design through the analysis of these materials.

Materials should never be discarded. I wondered if there was any museum or library where the ‘Hiroshi Kashiwagi Archive’ could be created in a coherent form. I first consulted Shogo Otani, Deputy Director of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, and then, thanks to the efforts of Tomio Sugaya, Director of NAKKA, it was decided to create the ‘Hiroshi Kashiwagi Archive’ in the archive within the museum.

Part of a bookcase. The keynote is a collection of books.

Differences between collections and archives

Archives differ from collections. In a collection, the contents are selected according to the intention of the collector. An archive, on the other hand, contains everything. In the case of an artist, apart from the finished work, everything is to be preserved, from esquisse and sketches related to the work, photographs and magazines that may be the source of inspiration, notes, diaries, letters, exhibition histories and records, contracts, and so on. Mr Kashiwagi is not a designer and has no works, but in addition to his writings, he is a member of national and local government and museum councils, organises international exhibitions abroad with the Japan Foundation, and works in the media, including educational programmes for NHK, and everything related to these is included in the scope of conservation.

As NAKKA only accepts materials related to work that he was directly involved with, the task of sorting the materials on the shelves was carried out by Mrs Mikiko, his daughter Mana and myself. Fortunately, Mrs Mikiko knew almost all of Kashiwagi's work and had organised and filed it away, so the sorting work went fairly smoothly. At the end of 2023, approximately 50 cardboard boxes were transported to the museum.

In autumn 2024, NAKKA, finished sorting and a list of the materials is available on the museum's home page. The actual items can be viewed on request at the museum.

Mr Kashiwagi's position as a design critic and design historian

Kashiwagi has been working under the title of design critic since the study of design history was still a new research field, and since his first monograph, Industrial Design Thought in Modern Japan, was published in 1979, he has authored 35 monographs, co-authored 28 books and contributed 79 articles and papers to journals and other publications. In addition, he has worked on numerous encyclopaedias, including the annual Gendai Design Jiten (Dictionary of Modern Design) and the Gendai Shakaigaku Jiten (Dictionary of Modern Sociology). In addition, he has supervised, planned and coordinated 31 exhibitions, appeared on NHK and other TV programmes and given lectures and symposia too many to count. He is a pioneer in the field of ‘design’, an academic discipline that focuses on the study of activities related to people's daily lives.

What I learnt from Kashiwagi

I myself am a historian, not a critic, but as a design researcher, ‘Hiroshi Kashiwagi’ is one of my goals. This is because there is much to learn from Mr Kashiwagi's work. In reading his books, we can see many of the issues that humanities and sociology deals with, from modernity, media, technology, power, economics, consumption, gender and war. I believe that the viewpoint from which these issues are explored is the essential question ‘What is design?’.

About the Japanese Design Archive

Researchers in design history, including myself, often conduct research in national and international archives. Many archives are located in special collections in the libraries of museums and art universities, and are visited by appointment, checking in advance what is needed for research from the list of resources published on the home page.

Typical archives include the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC, USA, the Paul Getty Research Institute in LA and the Design Library at the University of Brighton in the UK. For specific subjects and designers, materials related to Bauhaus are organised and stored as archives in the libraries of many universities and institutes, such as the Bauhaus Archive in Berlin for Bauhaus-related materials and the Illinois Institute of Technology Library in Chicago for New Bauhaus.

Japan lags behind the rest of the world when it comes to archives, but Keio University's Art Centre is probably one of the early adopters when it comes to art archives. 2018 saw the opening of the Art Archive Centre at Tama Art University, and initiatives to disseminate information outside the university, such as symposia and editing booklets The centre is also involved in symposia, editing booklets and other initiatives to disseminate information outside the university.

On the other hand, when it comes to design, most designers work privately, often in private ownership, or if they have a design office, they maintain it in their office. Materials owned by companies are not only not disclosed as trade secrets, but old materials are usually discarded. Where there is a strong relationship with designers, documents are stored and managed in-house along with the work, but in small numbers. In this sense, the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion's 'Ikko Tanaka Archive' is an excellent example of success, as is 'Hiroshi Kashiwagi Archive' at NAKKA. At present, the Yusaku Kamekura’s materials in the collection of the Niigata Prefectural Art Museum are still being organised by the curator in charge, although there is no specialised archivist.

Many designers who are sole proprietors probably have materials they want to keep as archives, but they don't know which to keep and which to discard, or how to organise them. Even if they eventually want to donate the material somewhere, after the person has passed away, the bereaved family may not know what to do with it, and it will eventually be discarded because there is no place to store it. If historically valuable material is disposed of, it will not remain in history. This is why it is desirable to establish archive centres that can receive donations, or design museums with archiving functions.

The non-profit organisation ‘Platform for Architectural Thinking (PLAT)’ is an organisation that can tackle this problem as well. We are investigating where and how much material is available on design in Japan, and connecting it to the network. The NPO Design History Research Centre Tokyo hopes to be an organisation that can provide research experience and knowledge to the network.

Enquiry:

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka、’Hiroshi Kashiwagi Archive’

https://nakka-art.jp/