Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Yoichiro Kawaguchi

CG Artist

Interview: 15 July 2025, 14:00–16:00

Location: Keio Plaza Hotel Lounge (Shinjuku)

Interviewee: Yoichiro Kawaguchi

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Yoichiro Kawaguchi

CG Artist

1952 Born in Tanegashima, Kagoshima Prefecture.

1976 Graduated from Kyushu Institute of Design, Department of Image Design (now Kyushu University)

1978 Completed postgraduate studies at Tokyo University of Education (now University of Tsukuba)

1992 Appointed Associate Professor, Faculty of Arts, University of Tsukuba

1998 Professor, the Research into Artifacts, Center for Engineering, University of Tokyo

2000 Professor, The University of Tokyo Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies(until 2018)

2010 Received ACM SIGGRAPH Award

2013 Awarded the Minister of Education Award for Fine Arts and the Medal with Purple Ribbon

2018 Inducted into the ACM SIGGRAPH Academy

2023 Designated a Person of Cultural Merit

Principal Awards

Eurographics Best Artistic Achievement Award, Shibata Prize (1984),1987 Grand Prix, France's New Image Exhibition; First Prize, Paris Graph Art Category; First Prize, Montreal Future Image Exhibition Art Category (1987), First Prize, Art Category, IMAGINA Exhibition, France; First Prize, High Vision Art Category, International Electronic Cinema Festival '91; Silver Prize, ARS Electronica '91 (1991); First Prize, Art Category, Eurographics (1992); Chairman's Award, MMA Multimedia Grand Prix (1993); First L'Oréal Prize Grand Prize, Tokyo Techno Forum Gold Medal (1997), Minami Nippon Cultural Grand Prize (2000), Fukuoka Prefecture Cultural Award (2002), The Society for Art and Science Society CG Japan Award (2009), ACM SIGGRAPH Award - Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement in Digital Art (2010), among others.

Description

Description

Yoichiro Kawaguchi is a pioneer of computer graphics (CG) in Japan. In the 1970s, during the dawn of computing, Kawaguchi had already designed a unique CG algorithm called the “Growth Model”. He created a method employing this as a function akin to DNA in living organisms. In the early 1980s, he presented astonishing works where two-dimensional CG self-replicated, attracting worldwide attention. This represented the birth of new life within the virtual environment of the computer, growing, multiplying, and evolving much like life forms on Earth – imagery humanity witnessed for the very first time. Kawaguchi's achievement as an artist lies in transforming CG from 2D to 3D, and then incorporating “time = movement” to create 4D expression. From the 1980s onwards, the development of CG in Japan was remarkable, and at its centre stood the artist Yoichiro Kawaguchi.

Kawaguchi has been active as a performer while also fulfilling various roles as a researcher and promoter of CG. As a researcher, starting at the University of Tsukuba and subsequently at the University of Tokyo's Centre for Artificial Systems Engineering and as a professor at its Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies, he engaged not only in research but also in nurturing the next generation. Notably, his work from 2006 to 2012 on ‘Technologies for Creating New Traditional Performing Arts Spaces where Ultra-High-Definition Imaging and Biologically Inspired Three-Dimensional Form Respond to Each Other’ involved researching and developing naturalistic and biological 3DCG expression methods. This pioneered subsequent fields such as projection mapping, 3D printing, and Ultra High Definition (8K). As a driving force, he contributed to the establishment and operation of the Digital Content Association as its Chairman, and also served as Chairman of the Convergence Research Institute, contributing to the promotion of CG. In recognition of these activities, he was selected as a Person of Cultural Merit in 2023.

And now, in this era of AI, Kawaguchi's creative drive burns ever brighter. Having weathered the pandemic, he now possesses an environment where he can focus entirely on creation. Speaking with the dreamlike enthusiasm of a boy, he describes his vision: ‘I want to give birth to life 500 million years from now and see it survive in outer space’ – a vision he pursues with both hands, digital in the right and analogue in the left. Kawaguchi's constant goal is to surpass his past self. He embodies the growth model he himself designed.

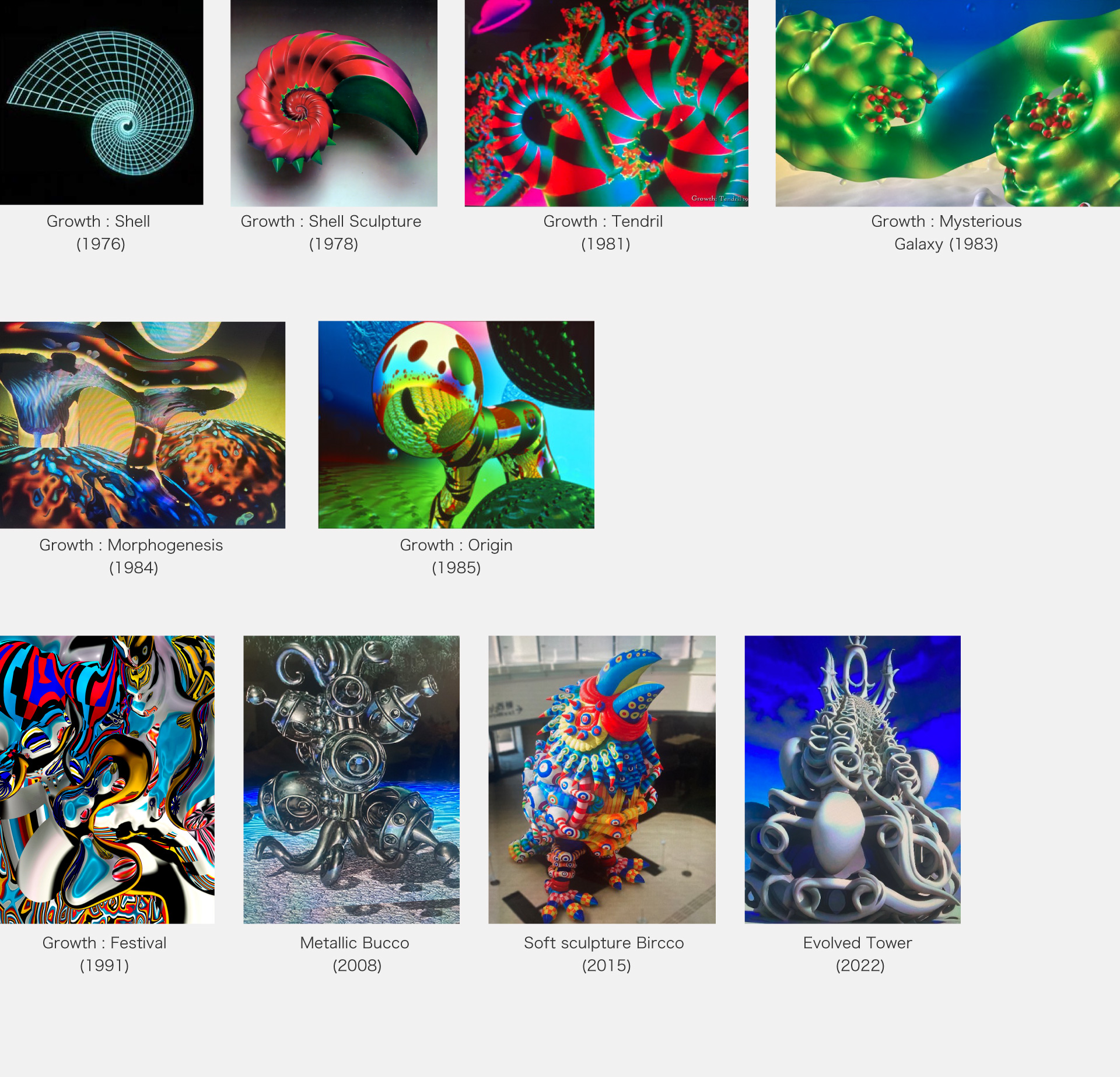

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Growth : Shell (1976)

Growth : Shell Sculpture (1978)

Growth : Tendril (1981)

Growth : Mysterious Galaxy (1983)

Growth : Morphogenesis (1984)

Growth : Origin (1985)

Growth : Festival (1991)

Metallic Bucco (2008)

Soft sculpture ‘Bircco’ (2015)

Evolved Tower (2022)

Interview

Interview

My starting point is the idea of whether life itself can be transformed into

art through a logical approach.

From Tanegashima to CG Pioneer

ー I believe your roots lie in your birthplace, Tanegashima. Could you tell us about your journey from childhood until you encountered CG?

Kawaguchi The origin of my creativity lies in my birthplace, Tanegashima. With the JAXA Space Centre's rocket launch facility nearby, I would gaze up at rocket launches, my fascination with space steadily growing, dreaming that one day I too would venture into the cosmos. At the same time, Tanegashima is a tropical island blessed with diverse natural environments – sea, land, and sky – teeming with varied wildlife. I was particularly captivated by the vividly coloured fish and marine life, in shades of red, blue, and yellow. My curiosity deepened: what shape and pattern do these fish scales form? What flavour and texture would they have if eaten? How do they swim? Furthermore, jellyfish existed on Earth as far back as the Cambrian period, approximately 500 million years ago. Whenever I spotted one, I found myself wondering how they had managed to survive on this planet all this time, and how it was nothing short of a miracle that one was now swimming so gracefully before my very eyes... Whatever I saw, I couldn't help but question its origins and fundamental nature. Meanwhile, shifting one's gaze from the sea to the land and sky, one finds vividly coloured plants and insects nurturing life, while the skies are filled with brightly coloured wild birds. I distinctly remember the beauty of one bird in particular, the “red-bearded” bird. In this way, Tanegashima felt like a natural museum, so I think it was only natural that I turned towards creativity from a natural scientific perspective. Had I been born in Tokyo, I probably wouldn't be who I am today.

ー Were you a child of nature?

Kawaguchi Yes, I loved being out in nature and moving my body. Tanegashima was simply paradise for a child; I could take in nature with all five senses. That’s the driving force behind my creativity.

ー I believe you possessed a particularly rich sensitivity towards the cosmos and nature. What was it that enabled him to transform this into creativity?

Kawaguchi It was realising that to explore the origins of the beauty in living forms and their movements, the element of “time” was indispensable. Ever since childhood, whenever I handled various living things, I'd playfully imagine them on an immense temporal scale – what form did they have a million years ago? How might they change a million years hence? In essence, my thinking and creativity have always existed along the vector of time. I was conscious that I was always observing everything by capturing it at the “here and now” moment within the flow of time. This sense of perception comes naturally when you live on Tanegashima, where the scale of time feels vast.

ー So what prompted you to start working with CG.

Kawaguchi My starting point was the idea of whether life itself could be approached logically and transformed into art. Normally, one would go to an art university, but for me, science and art were equally important. I entered Kyushu Institute of Design(now Kyushu University), Department of Image Design, as it seemed to offer both. There, I specialised in image design and encountered CG during my second or third year. The university was full of distinctive peers, and the mutual stimulation proved invaluable. When it came to actually creating CG, my interest lay in expressing life itself. I wanted to see what kind of art could be made by adding the element of “time”, so I absorbed the principles of algorithms and the fundamentals of computer languages. Being a nature-loving child raised on Tanegashima, I was like a blank slate. This allowed me to absorb knowledge like a sponge soaking up water. At that time, computers possessed only very rudimentary capabilities. However, just as I was embarking on my graduation research, a high-performance computer capable of graphical display was introduced. This allowed me to undertake research on CG amplification, where a collection of dotted lines rotates, expands, and contracts. Consequently, although it was line art, I was profoundly moved when the amplified motion, rendered for the first time in CG, moved on the display. It felt like witnessing the very moment of creation from nothingness. It convinced me that CG could visualise the invisible concept of time.

The CG works I worked on during my student days, “Pollen” (1976) led to the development of the growth model.

ー After graduating university, you went on to the graduate school at Tokyo University of Education (now the University of Tsukuba), didn't you?

Kawaguchi I still wanted to study in Tokyo, so I entered the graduate school at Tokyo University of Education, which had an arts-focused programme. But then I discovered the postgraduate students were drawing geometric figures by hand! I'd fully expected to study computer graphics, but instead I spent days on end just drawing figures by hand. Looking back, though, I was completely absorbed in it, and it proved a valuable experience. It was during this time that I met Eiichi Izuhara, who was working at the Agency of Industrial Science and Technology within the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry). Professor Izuhara advised me, ‘You should cherish your individuality, having grown up on Tanegashima,’ and further offered me the opportunity to become a research student. Fortunately, the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology had introduced equivalent high-performance computers, enabling me to finally engage fully with CG. Thus, my mornings were spent relentlessly sketching geometric figures by hand at graduate school, while afternoons involved CG research through programming at the Institute. I found myself leading a dual life as both a graduate student and a researcher. The gap between these two worlds was vast, yet experiencing both extremes simultaneously proved an invaluable asset. After graduating university, most people would have joined a design firm or similar. I chose an unconventional path to continue my research. It was a tightrope walk, but gradually I found myself able to pursue what I truly wanted to do.

ー It's remarkable how you taught yourself programming languages and algorithms.

Kawaguchi Back then, computer languages like ‘FORTRAN’ were mainstream, and with no textbooks available, I had to study from scratch entirely on my own. Even cutting-edge CG at the time meant graphics displays were unbelievably primitive, capable only of drawing simple line art. But taking on such challenges can sometimes lead to unexpected futures.

ー There's more to the story?

Kawaguchi As part of the development of the Tsukuba Science City, the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology was to relocate from Shimomaruko to Tsukuba. My mentor, Professor Izuhara, invited me, saying, ‘I've decided to go to Hokkaido. Would you like to come along? But I'm not fond of cold places, so I declined. Then, the professor introduced me to a position as a CG lecturer at the Japan Electronics College in Shinjuku. It was a privileged environment where I could freely use the school's equipment, but the computers there could only handle simple characters and text; creating the 3D images I wanted was impossible. But I'm a positive person by nature, and I felt it would be a waste to do nothing. I started a project titled “The Future of Tradition”. It was a kind of experiment: scanning Noh masks with a computer and then recreating them using points and lines based on that data. But as I kept at it, word got around that there was this bloke doing something interesting. One day, the dean of my technical college invited me to attend the SIGGRAPH International Conference in Chicago, presenting a chance to witness the cutting edge of CG. SIGGRAPH is a conference where America's top CG researchers gather. I met Hollywood creators and saw computers capable of rendering colour 3D images on display – it broadened my horizons. Above all, there were few artists or researchers like me working with a ‘growth-based × complex-based’ model. This convinced me that completing my unique CG work using my “Growth Model” would allow me to take the next step. Fortunately, shortly after returning home, the dean procured a computer costing several million yen. My dream of “visualising the invisible concept of time through CG” seemed to be drawing closer from the other side.

*SIGGRAPH (Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques) is an international conference organised by the Association for Computing Machinery.

Taking the Growth Model to the World

ー So you were already working on the Growth Model at that time?

Kawaguchi Once the equipment was in place, we refined the Growth Model while aiming for CG like what we'd seen at SIGGRAPH. We worked on making the 256 colours available on computers at the time appear as tens of thousands of colours. Since PCs back then had low processing power, we'd set programming tasks running until the last train home, then render all night long. It would finally be finished by the next morning. Careful time management was essential. It's a nostalgic memory now.

*Kawaguchi's self-replicating CG modelling algorithm, developed from the mid-1970s, which behaves like a living organism. A representative example is the algorithm creating spiral structures. By the 1980s, rich colours reminiscent of Tanegashima were introduced.

ー In 1982, you presented CG using the Growth Model at an international conference in America, which brought him to prominence.

Kawaguchi By the 1980s, word spread that ‘there's this bloke exploring unusual expressions of self-replicating systems,’ and overseas visitors began coming to observe. Around that time, I was fixated on the image of an infinite double helix with no beginning and no end, stemming from the idea that ‘all forms of life are moving, growing.’ In other words, from the fluid vortices on Earth to the spiral of the Milky Way galaxy, nature and living things exist within an infinite loop, a spiral of perpetual motion. Since CG can express loops and movement, I became engrossed in representing organisms that repeat birth, growth, and extinction over time, rather than static forms. Essentially, my keywords were generation and growth, evolution and genes, and sudden mutations – themes I've been exploring for fifty years.

ー At the time, you wrote in issue 6 of the design magazine AXIS: ‘By slicing the morphogenesis process—that is, the various stages of growth—along a temporal axis, one can discern how the laws and differences of the natural world influence form. The spiral is an exceptionally convenient shape for growth.’

Kawaguchi A renowned professor advised me regarding my Growth Model, suggesting I incorporate an ageing model alongside growth. However, I consider ageing to be an integral part of growth itself. I do not perceive ageing as ‘withered decay or decline’; rather, within the continuum of growth, I view ageing as part of the “evolutionary” process.

Beyond AI

ー Technology has advanced, and we are now in the age of AI. How do you incorporate AI into your creative work?

Kawaguchi AI has gained accelerated attention since the pandemic, but rather than being swept up in this trend, I'm sticking to my own pace, walking my own path. I'm more interested in how to transcend AI than how to master it. Looking back over the past fifty years, many friends around me who worked in CG have faded from the limelight; only a handful continue to be active. This shows that merely riding technological trends leads to being consumed. That's why, since the pandemic, I've been working under the concept of ‘Beyond AI’. In my view, creativity isn't a short-term battle but a long-term challenge, something existing within the vast flow of time, much like biological evolution. Therefore, rather than being absorbed by AI, pondering what expression beyond AI might look like promises a more interesting future.

ー You've mentioned “taking AI as your apprentice”.

Kawaguchi AI evolves daily, so I say I'm taking AI as my apprentice now. But next year, AI might surpass me. Hence ‘Beyond AI’ – it's better to see AI as my right-hand man. My competition isn't AI itself, but my past selves: 50 years ago, 10 years ago, 5 years ago. I'm bringing AI in to help me overcome those past versions of myself. My purpose now is ‘to surpass my past self and live joyfully.’

ー What kind of creative work have you been doing recently?

Kawaguchi Since around 2022, I've been employing AI in my creative process. One approach involves feeding my original works into the AI, then crossbreeding them to generate new creations. For instance, my existing works feature swimming, walking, and flying motifs inspired by living creatures, alongside jellyfish, crab, and octopus-like forms. I crossbreed these elements. Essentially, it's like passing traits from parent to offspring, offspring to grandchild, and so on through successive generations. Similar things could be done with conventional CG techniques, but by having the AI carry traits akin to biological DNA, I'm attempting to surpass the original works. Repeatedly crossbreeding original CG pieces leads to the birth of mutant descendants – some vigorous, others mischievous. Strangely, even in artificial CG, by the great-grandchild or great-great-grandchild generations, things can suddenly collapse and break down.

ー Is that to say AI has its limitations?

Kawaguchi At present, yes. That's why it's best to use AI now with a positive sense of playfulness; over-reliance requires caution. An acquaintance of mine, a professor, mentioned that when he experimentally tried to use AI to compile a pioneering design paper, it suddenly stopped working at one point. He said it would sometimes halt improvements and even regress.

ー At present, it seems best to treat AI as a companion you get along with.

Kawaguchi Indeed, when I tried feeding my own CG depicting a spiral from 50 years ago to the AI, the program couldn't understand it and froze. For AI, refining still images is straightforward, but when motion is introduced, as in my work, it suddenly becomes difficult. In the realm of design too, moving and non-moving elements are fundamentally different. For now, I simply try out various AI systems indiscriminately and select the ones I like. But predicting what will happen in three or five years is impossible. The current immaturity of AI is enjoyable and full of discoveries. I just keep trying things out. I'll leave the objective evaluation of AI to you all in the years to come.

ー Following the pandemic and Beyond AI, I get the impression that the scope of your work has expanded considerably.

Kawaguchi My work includes non-biological pieces using minerals and gemstones as motifs, so perhaps they appear different from the biological ones. When I feed images of natural minerals and gemstones into the AI and apply growth models, they don't grow because they aren't living things, but they do change according to a set algorithm, so I apply that. For instance, crystals don't change in nature, but I was curious to see what would happen if they stretched or bent in CG. Fundamentally, I'm interested in ‘movement’ and ‘time’. I want to see what happens at the boundary between the living and the non-living when something impossible in nature occurs.

ー How do you input mineral data into the AI?

Kawaguchi Fundamentally, it's the same for both living organisms and minerals. With AI, we input material properties, brightness, transparency, and so forth through trial and error. However, when it comes to creation, I simply cannot entrust it to others—I do it myself. The process itself is enjoyable, you see.

CG work ‘EGGY’ (2016) which attempted a crystal-like expression

ー I read in your article that since CG and AI can be copied endlessly, proving ownership of one's work is essential.

Kawaguchi Indeed, while paintings and sculptures can be signed, proving ownership of CG works requires alternative methods like NFTs*. In my case, it encompasses not only papers but also original paintings; essentially, it's about properly preserving the basis for digital works.

*NFT (Non-Fungible Token). A system whereby artists issue NFTs to prove the authenticity and ownership of their work.

ー This is also something I read in your text: Mr Kawaguchi stated that while Japan may struggle to become a world leader in AI technology itself, Japanese sensibilities hold an advantage in creative applications of AI.

Kawaguchi Japan may be lagging behind in AI technology development, but I believe we should focus intensively on niche areas within the creative field. There is potential if we can pioneer creative fields that leverage the unique, delicate sensibilities and meticulous attention to detail characteristic of the Japanese. For instance, Japanese cars, renowned for their precision and refinement, have taken the world by storm, and manga and animation are also highly regarded. I believe we should seek avenues that harness these uniquely Japanese traits: delicacy, meticulousness, and a sensitivity to the myriad phenomena of the universe. If we can discover and nurture such talents, I expect we will see tangible results in five or ten years' time.

ー Could you elaborate a little more?

Kawaguchi To use an analogy, jellyfish emerged 500 million years ago and evolved into sea anemones, starfish, and sea urchins while adapting to diverse environments. Yet the genes of these four species are almost identical.

My work operates on a similar principle to jellyfish: the goal isn't predetermined at the outset. Instead, it continuously changes and evolves through the ‘process = programmed’. I believe this resonates with creativity and design. For fifty years, I've pursued the algorithm of form, wondering how such biological evolution might be harnessed creatively – and I still see no end in sight. I believe Japanese designers could become far more creative if they studied and mastered the algorithm of form.

ー By 2027, the University of Tokyo, where you taught, will establish a new faculty, the College of Design, initiating education for new creative talent.

Kawaguchi Cultivating talent isn't about creating frameworks and proceeding systematically. What matters is the personal struggle of discovering new talent and figuring out how to nurture it. Sometimes, such talent emerges all at once, contemporaneously. Personally, I believe it's better for art and science not to fuse at a higher level, but rather to spark off each other. It's within that friction that sudden, positive transformations occur in both fields – that is, the Aufheben happens. We mustn't resort to facile fusion.

ー But the Japanese temperament seems ill-suited to progressing amid sparks flying.

Kawaguchi Indeed, creative work like design differs from art in that it often involves advancing projects with clients as a team or group. This necessity for the industry to function as such undoubtedly presents its own difficulties.

ー In Japan too, we're seeing the emergence of creators like teamLab's Toshiyuki Inoko, Yoichi Ochiai, and Rhizomatiks' Daito Manabe, who are developing new expressive realms and gaining global attention.

Kawaguchi In 2008, at the 10th anniversary event for the World Heritage designation held at Tōdai-ji Temple in Nara, I gained recognition for projecting ultra-high-definition CG of biological and natural imagery onto the vast walls that form Japan's traditional spaces, alongside various other experimental large-scale expressions. Though the term “projection mapping” didn't exist back then, I undertook experimental activities and creations, such as projecting images into large spaces for events like the Butoh performance with Kansai Yamamoto. In my case, it was positioned as research and experimentation at the University of Tokyo. However, design must be commercialised. That is to say, there is the aspect of systematising the production process, establishing a mass-production framework, and generating profit.

ー Is that where the difference lies between you and Kawaguchi and Inoko?

Kawaguchi I hadn't considered taking what I was doing to the point of commercialisation. If I had that time, I would have preferred to immerse myself more purely in creative research. Managing people, organisations, and companies is demanding work. What I find truly impressive is how Mr Inoko and Mr Ochiai have successfully established what I deliberately avoided as both a design and a business. Both studied at the University of Tokyo, and I know them well. I believe it's vital to step beyond the confines of academia and research to achieve what they have. I hope they persevere in the long term and I have very high expectations for them.

Digital Museum

ー Traditional art museums collected and exhibited physical objects like paintings and sculptures, but I imagine CG and AI creations are different. Digital art requires regular software updates, and the media itself has shifted from floppy disks, CDs, and DVDs to the internet and cloud storage today. This necessitates ongoing maintenance, which involves both effort and expense.

Kawaguchi That's true. While the programming and images of digital works don't degrade, they do need to be constantly converted to the latest version. Many of my works from 50 years ago can no longer be reproduced or have vanished because they weren't converted. Furthermore, works stored on videotapes or film have deteriorated to the point where they can no longer function as artworks. The latest digital works are fine, but those preserved on film or tape are difficult to recover. Therefore, we mustn't rely too heavily on technology. How to address ageing over time is one of the challenges ahead.

ー That said, in this day and age, art galleries have no choice but to embrace digital art.

Kawaguchi I'm also considering creating works where CG serves as moving paintings lasting several tens of seconds. Cryptocurrency is becoming widespread now, and digital art needs that kind of groundbreaking concept too. Instead of owning the physical object as before, I think it would be perfectly acceptable to have ideas like owning the usage rights to digital art.

Future Goals and Outlook

ー What are your goals moving forward?

Kawaguchi The immediate challenge is determining how far we can take Beyond AI. The emergence of AI was the major catalyst that prompted me to surpass my past self and forge the future. For me, the major difference between my pre-pandemic work and Beyond AI is that AI has become an extension of my arm, joining the production process I previously navigated through trial and error alone. I've come to realise that with a clear direction, involving AI allows us to delve deeper into creation and expand the range of expression – something you simply wouldn't know without trying. Recently, I collaborated with AI to create “Cosmic Butterflies”, evolving them through multiple generations to depict their form 500 million years from now.

ー I'd very much like to see that.

Kawaguchi Furthermore, I wish to involve astronomers and evolutionary biologists in the creative process, seeking new forms of creativity while being stimulated by their thoughts and ideas. Nowadays, time to immerse oneself purely in creativity is truly precious. Creating new lifeforms alongside AI, travelling to space and establishing those lifeforms on the lunar surface—such ideas might have seemed utterly preposterous in the past, but in the age of AI, they are no longer impossible. Thinking about such things is truly thrilling.

ー What about something a bit more accessible?

Kawaguchi Well, I'd like to try creating three-dimensional objects, not just CG. The immediacy of physical works is excellent!

ー The print you provided already shows a three-dimensional work, a massive one that seems to fill the entire space. Is this CG?

Kawaguchi I have created physical three-dimensional works, but what you see here is CG.

ー Really? It looks exactly like a real three-dimensional work placed in a physical space. I thought it was a scene from an actual exhibition.

Kawaguchi Creating physical pieces incurs significant costs, and securing storage space alone is a major challenge. With current digital technology, we can achieve this level of realism. AI simulates the space, allowing us to place the artwork within it and insert light, shadows, and other elements as needed to match the conditions. While difficult to realise with physical pieces, by harnessing AI, we can offer infinitely realistic experiences of time and space in various locations.

Soft Sculpture ’Cracco’ , 2016 Maintains its shape by circulating air through a blower

ー Please do make it happen. By the way, this year marks your 50th year of activity, doesn't it?

Kawaguchi That's right. As this year is the 50th anniversary, I'd like to challenge myself with a new form of exhibition or publication if possible.

ー What kind of exhibition would you like to create?

Kawaguchi My foundation has always been digital CG imagery. However, during the pandemic, I began creating hand-drawn sketches using oil-based coloured pencils on roll paper cut to 1×2 metre sizes, becoming utterly absorbed in this process daily. Consequently, I'd like to exhibit these hand-drawn works alongside my CG pieces. Come to think of it, back when my CG work first gained attention, visitors from abroad would often request sketches when I gave them CG prints. I suppose people still crave original, one-off pieces. So, during long journeys both domestically and abroad, I'd bring my sketchbook and gradually built up a collection of hand-drawn sketches. I also felt that for museums, art dealers, or research institutions, hand-drawn sketches would hold more value than CG. Then the pandemic hit. With no one to meet and no gatherings, I holed up in my studio and completed over 100 hand-drawn pieces.

One of Kawaguchi's hand-drawn works

ー That's quite something.

Kawaguchi Fundamentally, I find pleasure in balancing digital CG in my right hand with real, hand-drawn paintings in my left. So while the exhibition centres on CG video, I also want to display hand-drawn paintings and three-dimensional objects. Real stereoscopic 3D lenticular works are also fascinating. Previously, I recreated past works as large-scale lenticular pieces, around 2×1.5 metres, and exhibited them at the Japan Pavilion for the Venice Biennale '95. They were very well received. Ideas like this are limitless. lenticular They're quite rare these days. But I find that unique three-dimensional quality and materiality rather appealing.

ー I'm looking forward to it.

Kawaguchi I want to further invigorate Europe, America, and Asia through art and science! The Middle East is also worth keeping an eye on.

ー Finally, what is the current status of your works and archives?

Kawaguchi The digital works are stored on computers, while the original paintings and three-dimensional pieces are kept in storage. Organising them as an archive and the specifics of that process are still ahead of us. Up until now, I've simply wanted to focus on creation...

ー As a pioneer who pioneered Japan's CG field, preserving your works and materials is incredibly important. Digital works require essential maintenance, so please do take care of them. Hearing such positive news today has really lifted my spirits. Thank you very much.

Location of Yoichiro Kawaguchi's Archive

Contact

Yoichiro Kawaguchi Institute for Art and Science

contact@kawaguchi.net