Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Reiko Kawakami

Textile designer, Interior designer

Date: 28 November 2024, 13:30-16:00

Location: SWEDEN GRACE STORE

Interviewees: Reiko Kawakami

Interviewers: Aia Urakawa

Writing: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Reiko Kawakami

Textile designer, Interior designer

1938 Born in Fukuoka Prefecture

1957 Entered Joshibi University of Art and Design, Life Design Department

1958 Entered Kuwasawa Design School Living Design Department

1959 Graduated from Joshibi University of Art and Design,

Entered the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) as a research student. After leaving the institute, joined the Mayekawa Kunio Associates, Architects & Engineers

1960 Graduated from Kuwasawa Design School

1963 Left Mayekawa Kunio Associates, Architects & Engineers & Engineers and studied at the University of Arts, Crafts and Design, Sweden(KONSTFACKSKOLAN)

1966 Returned to Japan

1967 Founded Shinji and Reiko Kawakami Design Laboratory

1990 Founded Scandic House

1991 Form SKR established

1994 JID Award for Interior Space Awarded the JID Award in the Interior Space category

2002-2006 President of Japan Interior Architects / Designers' Association (currently Lifetime Member)

2017–2025 President of Scandinavian Architecture and Design Institute (currently Director)

Description

Description

Critic Hiroshi Kashiwagi states in his book "Interia dezain no hanseiki" (Rikuyosha, 2014) that "1960 seems to have been a nodal point for interior design in post-war Japan". He points out that the Air France Tokyo Office, designed and supervised by Charlotte Perriand and Junzo Sakakura, completed in 1960, attracted a great deal of attention and may have been the catalyst for the development of interior design.

Until then, the main designers of furniture for architectural spaces in Japan had been the Industrial Arts Institute and the design departments within department stores, but after 1940, furniture design departments were established within Japan's three leading architectural firms, with Tadaomi Mizunoe in Kunio Maekawa's office, Katsuo Matsumura in Junzo Yoshimura's office and Daisaku Cho in Junzo Sakakura's office, up-and-coming furniture designers. Since then, the collaboration between architects and interior products (furniture) designers has increased, with Kiyoshi Seike and Riki Watanabe, Makoto Masuzawa and Katsuo Matsumura, Kenzo Tange and Isamu Kenmochi, among others, establishing the Japan Interior Designers' Association (now the Japan Interior Designers' Association) in 1958 by Isamu Kenmochi, Riki Watanabe and others.

In those pioneering days of Japanese interior design in the early 1960s, Reiko Kawakami was a pioneering designer who worked on textiles for furniture for architectural spaces and studied textiles abroad. It was Kunio Maekawa who encouraged Kawakami to enter the world of textiles. Maekawa foresaw the success of designers working with interior fabrics and advised, "Textile design will become more important in the future, so if you are going to study in Northern Europe, why not study textiles" ("Hokuo interia dezain" (Taiyo Lecture Book; 3), Heibonsha, 2004). In the early 1960s, when overseas travel had not yet been liberalised, Kawakami travelled to Sweden to experience and learn about textile design, which was closely connected to daily life. After returning to Japan, she was involved in various architectural and interior projects and expanded his creative activities by entering the world of textile art.

She was the first woman to be appointed President of the Japan Interior Designers' Association, and has worked hard to improve the bottom line of the interior design world in Japan. She is also involved in promoting Scandinavian design in Japan through lectures and seminars as chairperson of the Scandinavian Architecture and Design Institute of Japan, and established Scandic House in 1990 to import and sell carefully selected quality Swedish furniture, and currently has a SWEDEN GRACE STORE in Yanaka, Tokyo, which Currently sells Swedish kitchen and interior accessories. Under her own brand ReikoKawakami, she has developed original textile designs, including the “1&2” carpet series for diverse spaces such as public, commercial and residential settings, as well as carpets utilising rush grass traditionally used for Japanese tatami mats.

In "Ineria dezain no hanseiki", Kawakami states. "Scandinavian furniture is (omitted) fundamentally based on the idea that it is not design for design's sake, but design for the people who use it every day". What Kawakami learnt in Sweden and passed on to Japan is not superficial colours and shapes, but the way of thinking about design itself.

The number of opportunities for textile designers in the Japanese architectural and interior world remains low, but a younger generation is certainly growing up. The path that Kawakami has paved must serve as a guideline for future generations. Such materials on the river have just been sorted out at the end of 2023. I visited the Sweden Grace Store in Sendagi, Tokyo, and spoke with them about their history and the related materials.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Interior Textiles

Sweet Room Tapestry (Keio Plaza Hotel, 1971), Textile Design (IBM Yamato Research Laboratory, 1985), Interior & Textile Design (Okayama Prefectural Government Building Extension, VIP Room, 1991), Textile Art & Interior Design "Stainless Fantasy"

(Yokohama Central Library, 1994), Interior & Textile Design (Morioka Grand Hotel), Textile Design (Shin-Yokohama Wedding Palace), Model House Design for Swedish Imported Homes, etc.

Original Brand

ReikoKawakami (Around 2003~)

Publications

Hokuou interia dezain"(co-authored), Heibonsha (2004)

Interview

Interview

It is strange that there doesn't seem to be a museum that deals with design archives

Fascinated by Scandinavian design

ー I understand that the SWEDEN GRACE STORE we visited today is run with your daughter (actress Maiko Kawakami) , when did it open?

Kawakami The shop opened in 2016. My daughter is the owner and I sometimes stand in the shop. In this shop, we carefully select and sell quality products that are rooted in our daily lives, mainly from Sweden where we used to live, as we wanted to introduce products that we can confidently introduce to our customers. In addition to tableware and interior accessories, we also sell glassware and cat goods designed by my daughter, and occasionally hold classes and workshops on the second floor. I used to teach Shinshu tsumugi, a Nagano silk weaving technique, and through this connection we recently held an exhibition of kimonos by a group that produces Shinshu tsumugi.

Inside the SWEDEN GRACE STORE in Sendagi, Tokyo.

ー I would like to ask you how you first became interested in design: were you influenced by your father's work for a construction company?

Kawakami My father was not an engineer, but a salesman. Perhaps I inherited my father's brother's lineage, who loved art. At that time, after the war, there was still no term or job title for interior design, and designers were considered to be a job for apparel. At that time, there were many magazines on interior design that my father ordered from our house, and I used to look at them from childhood. From around the sixth grade, I started copying the drawings in those magazines and drawing the floor plans of my own house. Later, when I was in the first year of junior high school, my father renovated my room based on the drawings I drew. The drawings were simple, though, such as adding a new window. That was the start of my interest in interior design.

ー After graduating from high school, you entered the Women's Art Junior College in 1957 and also studied at the Kuwasawa Design School.

Kawakami In 1958, the year after I entered Joshibi, the new Kuwasawa Design School building was completed in Shibuya. Because I agreed with the founder, Yoko Kuwasawa's approach to education and design philosophy, and because the Living Design Department, which now teaches interior design, was available, I studied at Joshibi during the day and began attending the evening courses at Kuwasawa. I I was part of the inaugural cohort at Kuwasawa's Shibuya campus. The teaching staff included individuals from the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute, established as an industrial promotion and research body under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), alongside renowned artists. Many students were already working professionals, which proved highly stimulating.

ー Then you were engaged as a research student at the Industrial Arts Institute, how did that come about?

Kawakami In the late fifties, Scandinavian design began to emerge and attract worldwide attention, and I began to think that I wanted to study in Scandinavia. At the time, I was more interested in furniture design than interior design in general, and I wanted to study in Denmark, where many of the finest examples of Nordic furniture design are concentrated. I once exhibited furniture I had designed at the Good Design Exhibition held at Matsuya Ginza, which opened in 1955. However, having been advised by those around me that it would be better to gain two or three years of work experience before studying abroad, I entered the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology as a research student after graduating from university. At that time, they were collecting and researching modern design products from all over the world, and I was also working on disassembling chairs and drawing full-size drawings.

My husband, furniture designer Shinji Kawakami, who is about 8 years older than me, also joined the Industrial Arts and Crafts Laboratory after graduating from university. He is the man in the photo of the “chair support surface experiment with snow moulds” on the page of industrial designer Mr Katsuhei Toyoguchi in the PLAT report you sent us. When my husband was still a newcomer at the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute, he was researching these chairs with Mr Toyoguchi. My husband will be 95 years old this year, but thanks to you he is doing very well. This shop also has it on display, but recently, someone expressed interest in acquiring the lighting fixture my husband designed, so I was making one. It consists of units combining materials such as paper and plastic, and won the gold prize at the first Yamagiwa Tokyo International Lighting Design Competition in 1968. Recently, a lighting manufacturer has commenced mass production, so it should be appearing on the market soon.

Worked on textiles in the office of Kunio Maekawa

ー How did you join Kunio Maekawa's office after working at the Industrial Arts Institute?

Kawakami Before that, I joined another design office, but I left after about six months because I felt the direction was different from what I wanted to do. I thought I would take it easy for a while, but the construction company my father worked for often worked with MAYEKAWA Kunio Architects & Engineers, and I think my father probably told someone in the office that our daughter was thinking of becoming a designer. My father thought it would be better for women to have a job in the same way as men, which I think was unusual at the time, and that's why he talked to the Maekawa Office. At that time, the Maekawa Office opened a furniture design department and furniture designer Mr Tadaomi Mizunoe was in charge of the department by himself, so I was asked if I would like to be his assistant. Mr Mizunoe had also been a research student at the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute, and was acquainted with my husband.

ー What kind of work did you do as Mr Mizunoe's assistant?

Kawakami The architectural design department was on the third floor of the Maekawa office, and there was a room for the furniture design department with a library corner on the second floor, where Mr Mizunoe and I were the only two people. The first project I was involved in was the Tokyo Culture Hall in Ueno. Mr Maekawa told me that I should meet with the manufacturers and propose chair upholstery for the hall's furniture. When I asked him why, he told me to give it a try even if I didn't have any experience, because there were times when colours were used and it would be better to have a woman's sense of style. I had no experience with textiles, but I was very interested in colour, so I decided to give it a try. The most difficult thing was the way Mr Maekawa expressed herself.

ー Maekawa told you in this book, "Maekawa Kunio deshitachi ha kataru" (Kenchiku Shiryo Kenkyusha, 2006), that he imagined the colour of the upholstery of the chairs in the Tokyo Bunka Kaikan in Ueno to be "the wine colour when a woman's lips are slightly purple because she was standing in cold weather".

Kawakami Mr Maekawa gave such poetic expressions to the other staff members. I told the person in charge of the manufacturer as it was, because the colours were not even in the colour samples, but I thought that was not good enough.

The library section attached to the furniture design department had many international books and magazines, which I began to read for study when I had time. The one that impressed me the most was the textiles of Alexander Girard, the designer and head of Herman Miller's textile department. I thought that if I could acquire specialist knowledge and skills and create textiles like these as a designer, I would be able to confidently explain them to manufacturers while making and showing them samples. I had wanted to study furniture design in Scandinavia, but I changed my mind when I realised that I also needed to study textiles in interior design, and my teacher encouraged me to go into textiles.

ー Mr Maekawa was one of the leading figures in post-war Japanese architecture as a jockey for modernism, and was the first Japanese to join the office of Le Corbusier, the French master of modern architecture, and became Corbusier's apprentice. From your point of view, what kind of person was Mr Maekawa?

Kawakami In the book "Maekawa Kunio deshitachi ha kataru", there are contributions from people who worked in his office, including myself, and it seems that he was very strict with the men. It seems that everyone was nervous when Mr Maekawa came and looked at them from behind or stood beside them while the people in the design department were working on drawings. Perhaps because of his experience of living in France, Mr Maekawa was gentle and lady-first towards the female staff, including myself. At the Maekawa office, there were only a few women other than myself, one in his secretary, one in the design department and one in the office. Mr Maekawa's clients had meetings in the library corner, and I once had the opportunity to talk with some prominent architects from abroad.

ー What do you think about Mr Mizunoe? I have the impression that he has not published any books and there are not many articles that talk about his personality.

Kawakami Someone who knew Mr Mizunoe well told me that she would not last long if I became her assistant. Mr Mizunoe is a very detailed person when it comes to her work, but I never once saw her get angry or irritated, she was very gentle and calm. Mr Maekawa's room was at the far end of the furniture design department, so he would walk past us in the morning and on his way home, and when he saw us, Mr Mizunoe would shake. His voice when he spoke to Mr Maekawa was also muffled, and I always had to step in between him and Mr Mizunoe to act as an interpreter. I would explain things to Mr Maekawa, reminding Mr Mizunoe, "This is how you think, isn't it? Looking back, I think I was young and had no fear.

Mr Mizunoe's atmosphere was similar to that of Swedish designer Mr Bruno Mathsson. Mr Mathsson was awarded the title of Professor by the Swedish Government. As well as his personality, there is a famous episode in which a drawing of the chair for the Kanagawa Prefectural Library, designed by Dr Maekawa, was always on Mr Mizunoe's drawing board, and he made slight adjustments every day, making about 100 corrections. This “S-0507” was sold by TENDO and is still a long-selling masterpiece. I have the impression that Mattsson made the same kind of detailed corrections to each leg many times, and through such careful work, he produced a number of wonderful pieces of furniture. Of all Swedish furniture, I like the chairs designed by Mr Mathsson the best. His masterpiece, EVA, has graceful curves based on moulded plywood technology, and the backrest and seat are woven with hemp belts, which provide a good amount of elasticity and enhance the seating comfort.

Studied at the Swedish University of Arts, Crafts and Design

ー Then you went to study in Sweden, but at that time it was rare to study abroad, wasn't it?

Kawakami I studied in Sweden in 1963. In Japan, overseas travel for tourism purposes was liberalised in 1964, and until then travel was permitted only for work or study. Illustrator and designer Ms Aoi Huber Kono, eldest daughter of graphic designer Mr Takashi Kono, studied at the Royal College of Fine Arts in 1960. Furniture designer Ms Midori Mitsui studied at the furniture department of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts from 1964, while lighting designer Ms Motoko Ishii worked for a Finnish lighting manufacturer from 1965. At that time, many Japanese designers went to the USA, and few people chose Scandinavia. Moreover, around that time, designer Miyoko Ohno travelled to Switzerland in 1966 as an overseas design trainee with the Japan External Trade Organisation, undertaking a training placement at Otto Graus Architects.

ー How were you able to study abroad?

Kawakami Initially, I had been considering going to Denmark, so I wrote to Ms Lis Ahlmann, the designer who had worked on the upholstery for Danish designer Mogens Koch's furniture. "Right now I am in an architectural office, where I see the need for textile design, and I would like to go and study. But I can't do anything yet, so I would like to learn how to weave textiles first." She recommended that I should study there rather than teach myself, as she was in her 80s at the time, and she told me about the Swedish University of Arts, Crafts and Design.

Moreover, when I joined Mr Maekawa's practice, it so happened that Mr Maekawa had just completed the joint design of the Swedish Embassy in Japan (the previous building) and the official residence with the Swedish architect Mr Nils Arbom. The furniture was designed by the architect and furniture designer Mr Carl-Axel Acking, who designed the famous “Tokyo Chair” furniture for the Embassy of Sweden. The textiles for Mr Acking's furniture were designed by Ms Astrid Sampe. Ms Sampe was a textile designer and head of the textile department at Nordiska Kompagniet, the largest department store in Scandinavia, where she worked with many architects and artists on commercialisation, and also worked with Isamu Noguchi and Charles Eames.

Inspired by Ms Lis Arman's recommendation to study at a Swedish university and struck by the beauty of the completed interior design at the Swedish Embassy, I decided to study in Sweden and conveyed this to Mr Maekawa. Mr Maekawa wrote a letter to Mr Acking, and Mr Acking introduced me to the headmaster of the Swedish University of Arts, Crafts and Design. With the help of these people, I was able to embark on my studies in Sweden. I am still very grateful to them.

By this time I was married to my husband, who decided to study furniture design at this university, and I opted for textile design. The university did not have an entrance exam, but required work experience. Having no prior experience in textile work, I learnt the fundamental techniques from a textile artist in Japan and took a summer course in textiles at the Swedish National University of Art, Craft and Design. My previously created furniture pieces were also submitted for assessment, and I managed to secure admission for September.

ー How was your actual visit to Sweden in the early 60s?

Kawakami I had read books and magazines, so I thought I knew roughly what to expect, but I felt that everything was different from Japan. I was impressed by the abundance of nature and the cleanliness of the cities, and I have visited many times since then, but my impression is that it was and still is the same. In Japan, it seems as if the economy cannot survive unless new products are released one after another every year, but in Sweden, I was impressed by the way old and new things are used carefully and for a long time in a way that suits the times and is well combined in daily life.

Of the Scandinavian textile manufacturers, Finland's Marimekko is well known in Japan, but Sweden also has a wide range of textile manufacturers: JOBS, with its highly skilled hand-printed textiles; Svenskuten, with its bold colours and motifs of flora and fauna; and many others. There were also a number of textile designers such as Mr Alexander Girard, Ms Lis Ahlmann and Ms Astrid Sampe.

At that time in Japan, the term "textile design" was still relatively uncommon, and even today it remains somewhat obscure, particularly to the general public. Among textile designers, Mr Hiroshi Awatsuji was a pioneer: he established the Hiroshi Awatsuji Design Office in 1958, and from 1963 he worked for FUJIE TEXTILE and others.

ー What did you study at university in Sweden?

Kawakami The university is a four-year institution, where students learn the basics in their first and second year and can create freely in the workspace from their third year. I had graduated from an art university in Japan, so I finished the basics in my first year and skipped to the third-year class the following year. So I was able to spend more time on practical production skills than other students.

The most important thing I learnt was about colour. In textiles, I received guidance from Professor Edna Martin, Head of Department, and gained valuable experience. She is the chief art director of the Handarbetets Vänner (the Association of Friends of Textiles) and has been instrumental in turning original paintings by various artists into tapestries, embroideries and carpets. Textiles are interesting because the threads can be freely combined to create magical colour schemes.

ー Your first piece of textile work caught the eye of the King of Sweden, who bought it.

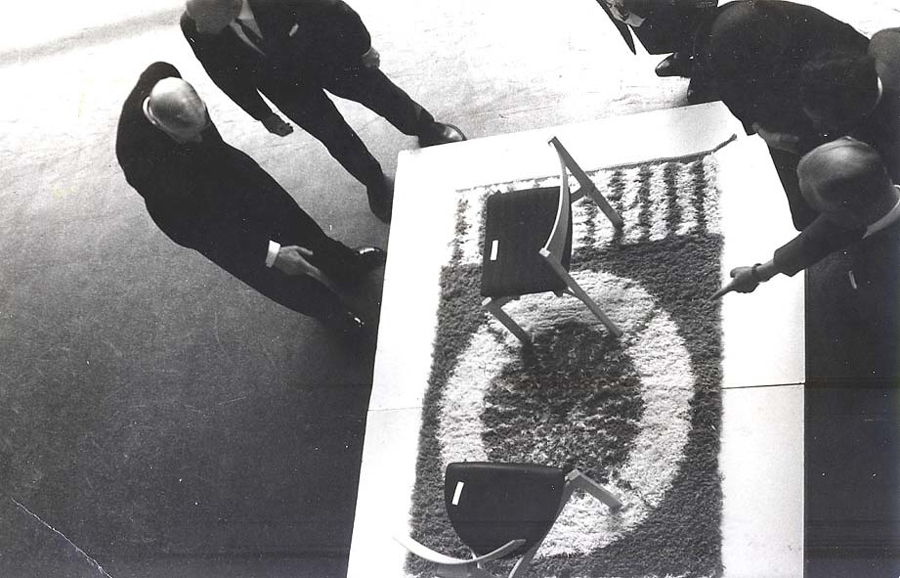

His Majesty the King of Sweden viewing textile works by Reiko Kawakami. The chair is designed by Shinji Kawakami.

Kawakami I made a rug to put under the chair to coincide with the presentation of a chair designed by my husband on campus. It is an artistic piece that can also be hung on the wall, and it is the first piece I have made with textiles. I like old Japanese things, and I have often used serpentine motifs in my work before, and I came up with the idea of a rug with a serpentine design. Japanese kimonos are particular about what you don't see, such as elaborate designs and flashy colours for the lining of cuffs and hems. Drawing inspiration from this, we used Nordic hemp thread. When laid out normally, it displays a natural colour tone, but as diverse coloured threads are incorporated into the top, bottom, left and right edges, shifting your perspective reveals these colours. The King of Sweden always attended students' exhibitions when they were held. On one occasion, when summoned by the head professor, I was told directly by His Majesty that he had been searching for something to lay in his own bedroom and had taken a particular liking to your work, requesting that it be given to him. I People around me advised that I should keep my first work to hand, but as His Majesty the King took such a liking to it, I decided to hand it over to him. I later heard that the piece subsequently entered the King's collection.

Creation of textile artworks in architectural spaces

ー Your work has been archived in the collection of the King of Sweden. What kind of work did you do after you finished university and returned to your home country?

Kawakami Once back home, when my daughter was in second grade, I consulted with the school and went to Sweden again with her for a year. A university friend shared an atelier space with me at a collaborative studio facility for artists supported by the city council. There, whilst undertaking work for a Japanese company, I also carried out upholstery work on chairs designed by Mr Bruno Mathsson. It was a printed fabric, not a woven fabric, and I corresponded with the company that produced it for mass production. I was a close friend of Mr Mathsson 's for many years, as it was a family affair.

Later, I happened to be able to buy a room in a Swedish apartment that a friend had, so I went there several times a year to work. In Japan, while working as a part-time lecturer at Musashino Art University and Showa Women's University, I entered the world of textile art, working not only in textiles but also in interior and furniture design. I felt that there were limits to what I wanted to express with mass-produced textiles alone, and I had always been interested in the world of art, so I created works of art and presented them in exhibitions. An architectural firm that saw my work approached me, and I began to create textile artworks in architectural spaces. The first textile artwork I created after returning from Sweden was for the Keio Plaza Hotel, which opened in 1971, with Mr Isamu Kenmochi as the general producer of the space. People from a variety of fields participated in the project, including ceramicist Mr Yusuke Aida, artist Ms Toko Shinoda, painter Mr Matazo Kayama, and designers Mr Hiroshi Awatsuji and Mr Riki Watanabe.

ー You have also done work for the Yokohama City Central Library and the Okayama Prefectural Government, where was this work commissioned from?

Kawakami My public-sector work often involves being approached by TAKENAKA CORPORATION and MAYEKAWA ASSOCIATES, ARCHITECTS & ENGINEERS. During Mr Maekawa's lifetime, I was not working professionally; it was only after his passing that I was given the opportunity to create works tailored to specific buildings. At Yokohama Central Library, I created a work to be displayed in the entrance hall. As it is a library, the concept involved achieving an acoustic effect without being overly formal, aiming to realise an art piece resembling a textile. Natural materials such as cotton and wool could not be used due to fire-retardant requirements. After much consideration, I proposed a tapestry-like woven piece using stainless steel, iron plates, and glass, treating these materials as threads. The aim was to create a design that would give a sense of tranquillity and peacefulness, and the lighting would create a warm expression, and because it is metal, the colour would deepen over time. It was the most difficult piece I have ever worked on, but it has become my masterpiece.

Work on textiles for architectural projects typically commences after the overall design concept has been finalised, meaning involvement is often partial. However, for projects such as Yokohama Central Library and Okayama Prefectural Government Building, I was privileged to be involved in the interior spaces more comprehensively, including the textiles.

At Yokohama Central Library, it was created using stainless steel, iron plates, and glass.

ー In recent years, many young textile designers with a lot of individuality have emerged in Japan, but when we talk to them, they say that they would like to work on textiles for architecture and interior design, but find it difficult. How do you feel about the current situation in the Japanese textile design world?

Kawakami I feel that not much has changed in the past or now. In the Japanese architecture and interior design industry, if there is a special budget for a project, textile designers may be asked to develop textiles, but in general I feel that there is little demand for their work. Textiles deteriorate over time, so I think there is also a bottleneck in terms of maintenance costs.

Then, when you are a student, you can create your work in the workroom on campus, but after graduation it is quite difficult for an individual to have access to expensive machinery and equipment. In Sweden, there is a joint workshop facility for artists, which I also used, which was donated and supported by the city and the local council, where I was able to expand my field of activity while balancing my own research and work. I feel that such an environment is also necessary for creators. In Sweden, the “1% for Art” law, which allocates 1% of the total cost of public buildings to public art, was enacted in 1937, one of the earliest in Europe. In Sweden, there is a tendency to treat textiles as art, with silk-screened and woven tapestry works adorning various public spaces, including schools, banks, hospitals, community centres and churches. “1% for Art” seems to be gaining ground in Japan as a legislative initiative. If textiles by young people are increasingly incorporated into public buildings in the future, the situation may change.

ー I saw some pictures of the interior of a friend's house that you visited during your stay in Sweden, and textiles have become a part of the lifestyle and culture, and I felt that this was also different from Japan.

Kawakami In Sweden, using tablecloths and napkins is an everyday thing and textiles are part of daily life. In Sweden, everyone drinks a great deal of coffee. While I was studying abroad, during an afternoon coffee break, someone who had been weaving removed the finished cloth from the loom, spread it over the table, and we all drank coffee together. I was also surprised to see tablecloths laid on the outdoor tables at the summer house, and at my daughter's school parents' association meeting held in the evening, where they laid tablecloths, lit candles, and chatted over coffee and cinnamon rolls. In Japan, if there is a beautiful tablecloth, you might put plastic over it to prevent it from getting dirty. One reason interior textiles have not gained much traction in Japan may well be differences in lifestyle culture and mindset.

The sale of the mansion was an opportunity to start sorting out the materials

ー I would like to ask you about the archive story from here, and I heard that your daughter helped you to declutter at the end of last year.

Kawakami After my wife and I returned from Sweden in 1966, the flat we were living in was like a storage unit, so we decided to get rid of it. The condominium was built by my father's company. During construction, design changes were made: walls were removed to create a spacious open-plan area, the flooring was replaced with parquet, and the furniture was custom-made. It was a time when more and more people in Japan were interested in interior design, but it was rare to refurbish a flat in this way. At that time, I contributed interior design proposals to magazines and even recreated a corner of my own home in an NHK studio to give interior design lectures on a programme. I had a lot of things that I was very attached to, such as materials from that time, Scandinavian furniture and vintage tableware, and it was difficult to get rid of them.

However, we couldn't just leave it there, so last year we decided to take the plunge and contact a real estate agent to get rid of it. My daughter happened to write an article on the internet or something about how she was going to get rid of the things in the house, and a TV station saw it and contacted us, and we were invited to interview and film the process in a programme about decluttering. The property had been sold and there was a deadline, so I had very little time to sort out what was there. In the hectic two months or so at the end of last year, we put what we thought we needed into storage for now.

What we appreciated was the network that the TV programme had. In particular, we were introduced to a specialised bookshop for books on interior design, and the owner of the shop was very excited to see some of the rare books. He also took some postcards from a designer he knew, as he thought they were valuable. Later, an architect who frequents that bookshop was also pleased. He said that he was thinking of collecting things from people of that era and compiling them into a book, and that one of his notes and receipts were among our materials. It is strange how even a piece of paper can be important to someone who needs it, but if they don't know its value, they may throw it away.

ー What are the drawings, sketches and photographs of your work?

Kawakami I haven't been able to sort it out yet, because I have some in storage and some where we live now. We have enough for both my husband and me, so it is very difficult. I have discarded the furniture my husband designed because it took up too much space, but I have kept the hand-drawn drawings. I kept the textile work I presented in my first exhibition after I returned to Japan, but I discarded it. The rest of my work is in storage. I really wanted to keep the design drawings, but I took photos of them with my smartphone and made digital images of them and disposed of most of the originals. I have a few design drawings left that I am very attached to, and I still have a lot of books, and I am wondering what I am going to do with them. I think all designers have the same problem. Come to think of it, I haven't had any conversations with people of the same generation about what to do with these materials.

ー Ms Kawakami, as a textile designer, how do you wish to preserve your own archive? Furthermore, how do you believe textile archives should be preserved?

Kawakami I feel it is very important to preserve works so that younger generations have the opportunity to encounter the creations of their predecessors from a historical perspective. Naturally, I also want my own works to endure as long as possible.

However, I recognize that storing large works created for exhibitions, for example, has inherent limitations for an individual. Additionally, works using fabric materials like textiles present challenges due to their highly delicate preservation requirements, such as humidity control. On the other hand, works like "Stainless Fantasy", which I created for the Yokohama Central Library, use materials like stainless steel, iron plates, and glass instead of fabric. These can be preserved long-term with maintenance like washing. However, performing this maintenance requires scaffolding, and I understand setting it up involves considerable expense. This highlights how textile works present difficulties not only in "storage" but also in "maintenance and management".

ー There are archive museums for garments in Japan, such as the Kobe Fashion Museum, but are there any museums in Scandinavia or elsewhere that hold archive material on textiles?

Kawakami There is no museum in Sweden that archives textiles, and I don't think there is an independent design museum that deals solely with design. Previously, as a founding member of the Japan Textile Design Association, I had the opportunity to discuss this with Mr Awatsuji and others. Yet, upon reflection, it strikes me that museums dedicated to design archives seem to exist only in name. It is rather curious, isn't it?

Come to think of it, I was close to the designer Ms Miyoko Ohno, who was featured in the PLAT report you sent to me, before her death. Ms Ohno and I and Ms Mineko Yamamoto were members of the Japan Interior Architects / Designers'Association, and as there were not many women in the Japanese design world at the time, and as we were almost the same generation, we attended meetings abroad together and were also close friends in private. Ms Ohno passed away in 2016, a little too soon.

ー I think so too. We would like to continue to speak to as many people as possible who have laid the foundations of the Japanese design world. Thank you very much for your valuable talk today.

Enquiry:

NPO Platform for Architectural Thinking

https://npo-plat.org