Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Isamu Kenmochi+Tetsuo Matsumoto

(Kenmochi Design Associates)

Product designer, Interior designer

Date: 21 November 2017, 15:00 - 17:00

Location: Kenmochi Design Associates

Interviewees: Tetsuo Matsumoto (Kenmochi Design Associates)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Keiko Kubota, Aia Urakawa

Author: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

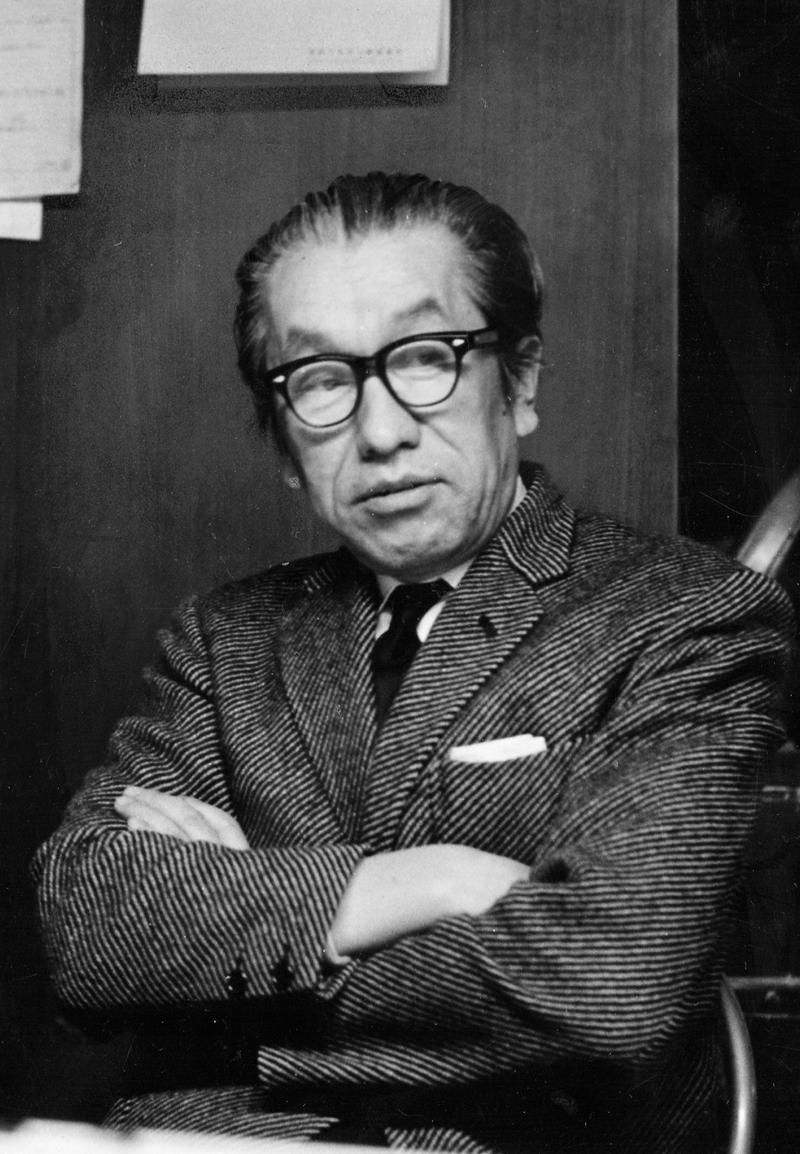

Isamu Kenmochi

Product designer, Interior designer

1912 Born in Tokyo

1929 Entered the Department of Wood Crafts at Tokyo Polytechnic High School (now the Faculty of Engineering, Chiba University)

1932 Joined the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), studied under architect Bruno Taut

1955 Founded Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates

1971 He Passed away

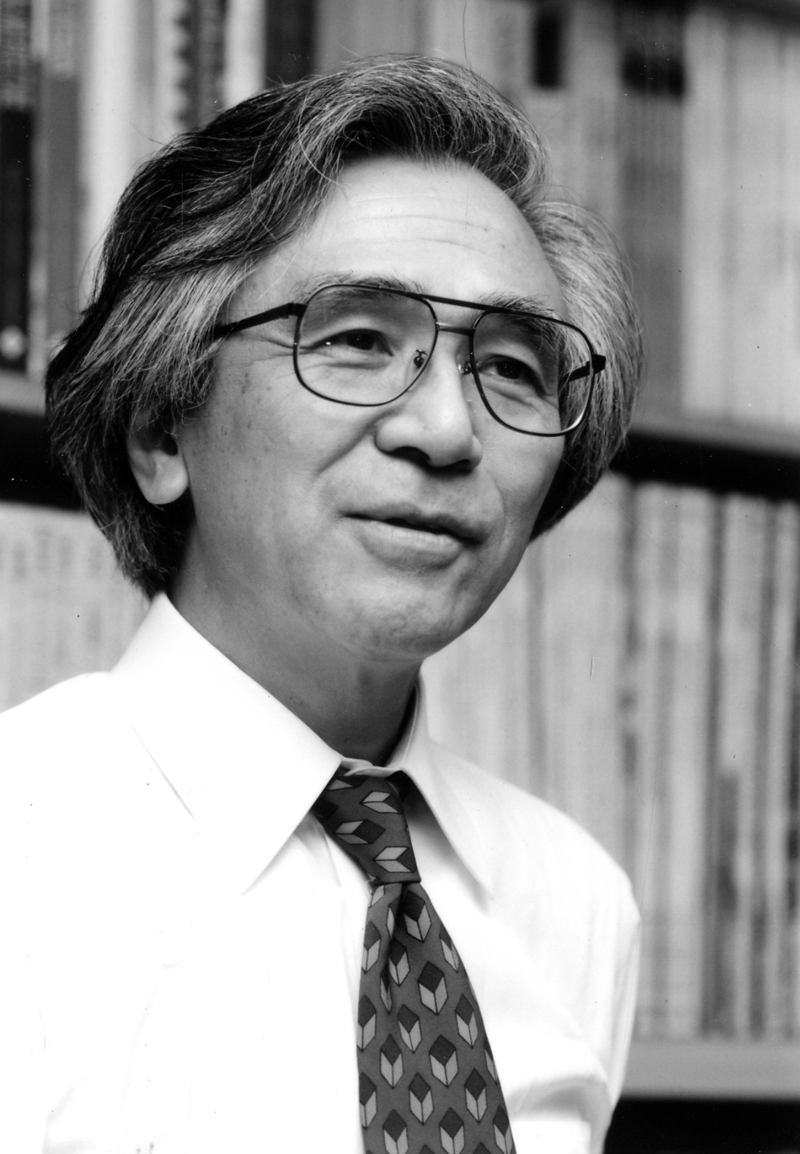

Tetsuo Matsumoto

Product designer, Interior designer

1929 Born in Tokyo

1953 Graduated from the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering, Chiba University and worked as a technical officer at the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute, Industrial Technology Research Institute, Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry)

1957 Joined Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates

1971 President of Kenmochi Design Associate after Isamu Kenmochi passed away

Description

Description

Isamu Kenmochi worked with Riki Watanabe, Sori Yanagi and others to enlighten design and improve the lives of Japanese people at the dawn of post-war design. At the Ministry of Industry and Commerce (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry), where he started his career, he learnt from architect Bruno Taut about the "normative prototype of the chair", and in 1952 he became the first Japanese designer to visit the USA to broaden his knowledge, and was greatly influenced by his encounter with Charles Eames. On his return to Japan, he was involved in the founding of the Japan Industrial Designers Association, which aimed to establish and improve the profession of industrial design, and in 1955 he was involved in the establishment of the JAPAN DESIGN COMMITTEE, which campaigned for "Good Design Enlightenment", and developed its activities.

In product, he is famous for the container for "Yakult", which became a world-renowned anonymous product. In furniture, many of the chairs he produced for architectural spaces were later commercialised and have become long-sellers. The Hotel New Japan rattan chair "Lounge Chair" was the first Japanese furniture to be selected for inclusion in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in 1964. In interior design, he often collaborated with architects and demonstrated his skills not only as a designer but also as a director. One such example is the "Keio Plaza Hotel", the first skyscraper hotel in Japan. The hotel brought together renowned designers and artists in the fields of furniture, textiles, fine arts, ceramics and landscaping, with Kenmochi acting as general advisor and taking the lead. Unfortunately, he took his own life on the day of the opening of the Keio Plaza Hotel, ending his short life, but his achievements in leading the post-war design world and introducing Japanese design to the world will go down in history.

After Kenmochi's passing, Tetsuo Matsumoto took over the office and, in addition to interior and furniture design, as a member of the Transportation Design Organization (TDO) with Kazuo Kimura, Tezeni Masamichi and Tetsuo Fukuda, worked on a wide range of projects, including the interior and exterior of bullet trains and other railway vehicles, and is still working on various projects. We asked Tetsuo Matsumoto about his time at the Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates and the archives of it.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

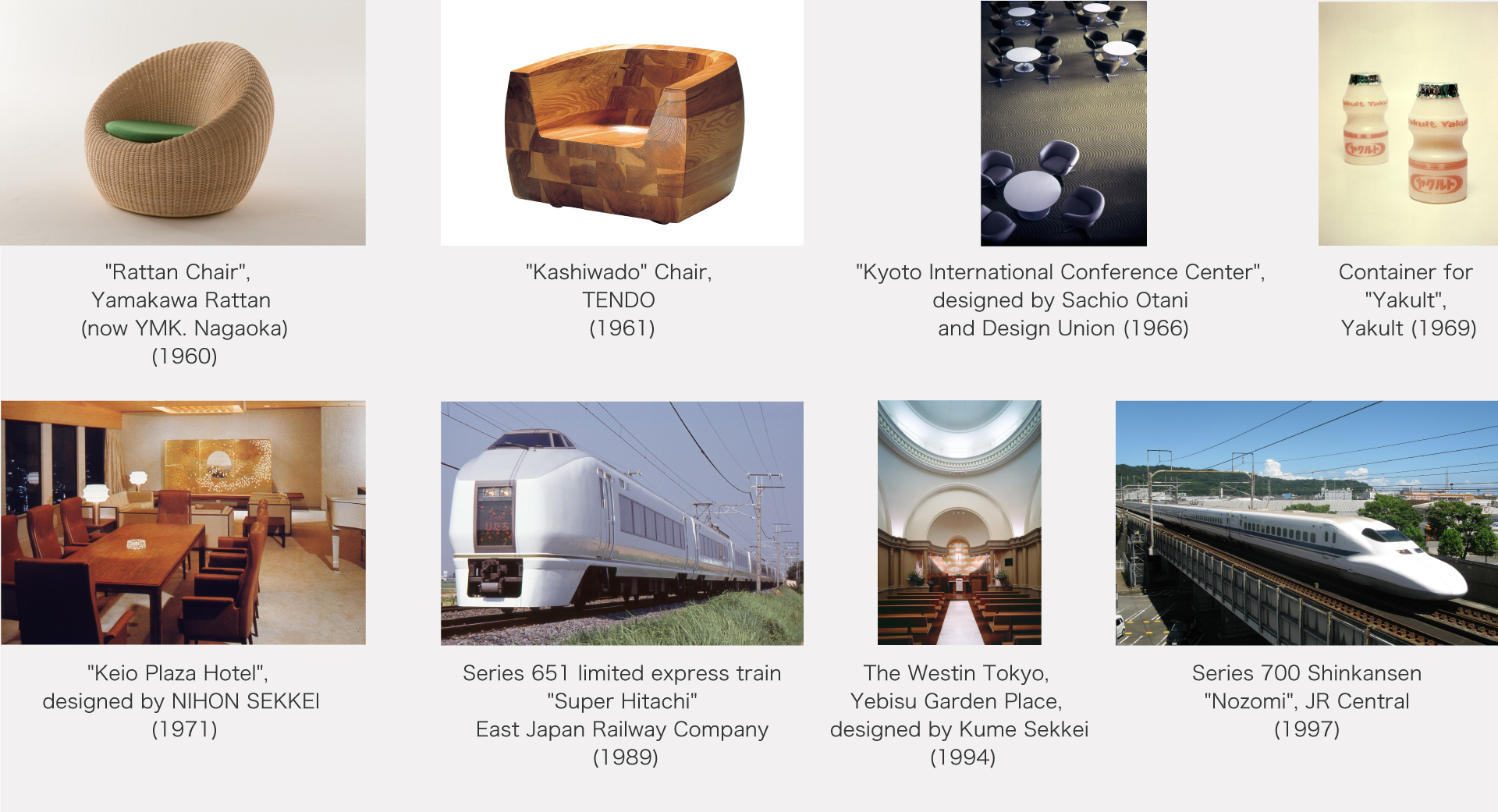

〈Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates〉

Interior

Kagawa Prefectural Government Office, designed by Kenzo Tange (1958); Hotel New Japan, designed by Takeo Sato Design Office (1960); Kyoto International Conference Center, designed by Sachio Otani (1966); Japan Airlines B-747 (1968); Keio Plaza Hotel, designed by NIHON SEKKEI (1971)

Furniture and products

"Stacking stool" Akita Mokko (1958); "Rattan Chair", Yamakawa Rattan (now YMK. Nagaoka) (1960); "Kashiwado" Chair, TENDO (1961); "Chair T-3048M" TENDO (1961); "Stackable Ash Tray" Sato Shoji (1963); Container for "Yakult", Yakult (1969)

〈Kenmochi Design Associates〉

Interior

Yakult Honsha and Hall (1972); Nagoya Kanko Hotel (1972); Recruit G8 Hall and Conference Room (1981); Yebisu Garden Place (Sapporo Breweries head office building, executive floor, Westin Hotel Tokyo wedding hall, chapel and Japanese restaurant) (1994); GINZA NIKKO HOTEL (2009)

Furniture, products and signs

Various Duskin products (1972-); seats for linear motor car, KOTOBUKI (1986); "Super Hitachi" JR-EAST (1989); cruise ship "Asuka" NYK Line (1991); "Shonan Liner" JR-EAST (1992); "international flight furniture signage for new Takamatsu Airport passenger terminal building" (1992). (1997); "MAX E1 series", JR-EAST (1994); Series 700 Shinkansen "Nozomi", JR Central (1997); furniture for the official room of Prince Akishino's residence (2004)

Books

"Kenmochi Isamu no sekai" Kawade Shobo ShinSha (1975); "Kenchikuka no hirogari Mumei no koukyou dezain" Tetsuo Matsumoto+Written by Tetsuo Matsumoto's Book Making Society, KENCHIKU JOURNAL (2017)

Interview

Interview

As for archiving, I think it's best to let my next, next generation thinks about that issue

In the 50s it was called "interior decoration", not interior design

― At present, there is a generational shift among Japanese architects and designers, and as the first generation of architects and designers age and pass away, one of our NPO projects is to ask them how their works and materials are being preserved and maintained, and to document and preserve their works and materials. There is talk of a design museum in many places at the moment, but our aim is to explore the current situation before that.

Today, I would like to ask you about two main themes. One is the current status of the materials and drawings of Mr. Kenmochi, who pioneered post-war design in Japan, and the other is how the office under his personal name was taken over after his passing. I think there were many possibilities, but I would like to ask you about your awareness of the issues and methods involved in making the decision and actually running the office.

Matsumoto People talk about design museums all over the place, and they all have various things to say. When the world's economy improves, such talk appears, and when the economy worsens, it disappears. Recently, a book like this ("Kenchikuka no hirogari Mumei no koukyou dezain") has been published, which also includes a summary of me.

― It has a chronology and it's highly documented. That's one valuable archive. How long did the interview take?

Matsumoto It took about four days. I was surprised that the editor did a lot of detailed research beforehand. Our staff made the chronology. It took a considerable amount of time and a lot of hard work.

The book starts with my childhood. I really wanted to be an architect, and in 1949 I entered the Faculty of Engineering at Chiba University as a first-year student to study architecture. But none of them took me. Japan was still under occupation at the time, and Japanese architectural firms were designing houses for Americans and there was a lot of work, but by the time we graduated from university, such work had almost disappeared.

― Mr. Kenmochi was also a graduate of Tokyo Higher School of Arts & Technology, the predecessor of Chiba University.

Matsumoto Kenmochi graduated in 1932, when I was three years old. It was a wood craft department, so he was quite familiar with woodworking techniques. At that time, most people who wanted to design joined the decoration department of a department store, but Kenmochi joined the Ministry of Industry and Commerce, which later became the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. He really wanted to be a painter, but his father, a retired army major, would not allow it. He was allowed to enter the Tokyo Higher School of Arts & Technology because he wanted to learn techniques.

― I would like to ask you about the archive, what is the current state of Mr. Kenmochi's drawings and sketches?

Matsumoto All the drawings of the products I worked on at TENDO during the Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates period have been digitised. In the post-war 50s, interior design work was very different from what it is today: it was what we call "decoration", such as choosing wallpaper and curtains for a blank space. Some furniture was made by furniture manufacturers such as TENDO and KOTOBUKI, and later commercialised. That is why many of Kenmochi's works were made by such furniture makers.

― How did you go about digitising TENDO’s drawings?

Matsumoto We organised the drawings on our side and gave them to TENDO to be digitised. They are all large, almost full-size drawings. Kenmochi believed that a full-size drawing of one-thousandth of an inch was a design drawing. He also did tenths and fifths of a drawing, but he used to say that if he didn't eventually get to a full-size drawing of a tenth of a drawing, the design was not finished. At the time, most offices did not draw up full-size drawings. They end up with a tenth of a drawing, and then the manufacturer or factory draws the rest. At the time of the "Kyoto International Conference Center", our office even drew the full-scale drawings and handed them over to the manufacturer, who was very surprised. They told us, "We are sorry that you have done all the drawings that we do".

"A design that is not backed up by technology is not a design at all"

― What was the reason for sticking to full-size drawings?

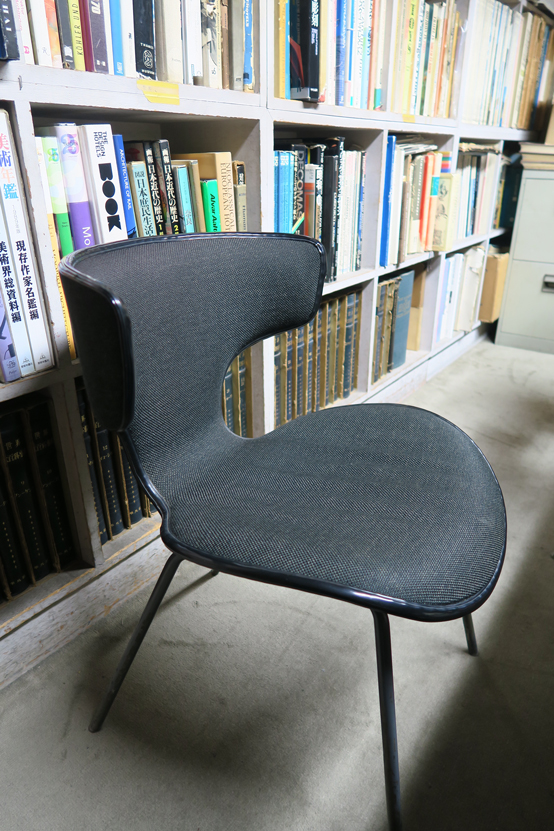

Matsumoto To get a sense of scale. It is also necessary to communicate details to manufacturers and factories. The chair I am sitting on now is a development of the one I designed for the "TOTSUKA COUNTRY CLUB". Instead of simply laminating the vinyl fabric together, I first put the fabric on the plywood inside, fixed it with nails and then covered it further to hide it. We also draw those details on the drawings to tell the manufacturer or the factory about the structure. With architecture, you may not have to go that far, but with furniture you have to draw all the details to get the message across. Some designers don't even draw the plans. They just say, "Make it like this" and the manufacturer draws the plans and makes it for them. Kenmochi never did that. Kenmochi used to say, "Don't design furniture if you don't know how it will be made" and "A design that is not backed up by technology is not a design". In our office, we still draw full-scale drawings.

― You were also involved in technical research and experiments to realise such furniture, weren't you?

Matsumoto I think Kenmochi really wanted to work on the mock-ups. Charles Eames had a workshop in his office, which also did its own work.

To do this, they have to be able to draw full-scale drawings properly themselves. They created a system whereby they would buy it from furniture manufacturers. In Japan, it is difficult to have a workshop in an office due to space limitations. There is no space for that, as the building only has three floors totalling 90 tsubo (3.5 square metres). In the beginning, we used the first floor as a showroom to display our work, but as the number of staff gradually increased, we started to use the whole floor as an office. Kenmochi's room was on the second floor and I was on the third floor.

― In the case of the chairs, were the mock-ups made by the manufacturer?

Matsumoto Yes, that's right. We asked the manufacturer to make them, and then we checked them together with the drawings and made adjustments as we went along. For the mock-up, another full-scale drawing is made at the factory.

― What is the difference?

Matsumoto These drawings contain the information needed for production and vary depending on the machine used. We have an approximate idea of what we would be able to produce with that machine. Nowadays, production is done by computer and drawings are now digitalised, so production is much faster.

Preserving production techniques is part of the archive

― In the days of Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates, you often collaborated with architects such as Mr. Kenzo Tange. I think, you went on to design the interiors and furniture to suit the space. How did you communicate with the architect?

Matsumoto Surprisingly, architects are not very specific. With Mr. Tange, we often decided through discussions rather than having a firm image from the start. For example, for the chapel chairs in the "Tokyo St. Mary's Cathedral", we made a partial full-scale model, and based on that we made various proposals and discussed them before making a decision.

― Are the original pieces of furniture you first made for such projects still at TENDO and other companies?

Matsumoto I don't think there are any left at TENDO. Some of the original furniture is on the third floor of my house. Some of them ended up as prototypes and were never actually commercialised. The taxation system has changed a bit now, but if it's something that can be sold or sat on, all prototypes and mock-ups are taxed. So it is considered as a piece of stock. That is why manufacturers and factories like TENDO destroy prototypes and mock-ups once they are finished as products. But I didn't want to see something I had worked so hard to design and painstakingly create burnt, so I asked TENDO to contact me when it had to be destroyed, and I started storing it at my home. We don't have that many, but we have some on the third floor of this building. It's still nice to have that kind of furniture that has become a product, but the building is suddenly demolished and the furniture is destroyed with it.

― In Japan, there are museums and universities that have collections of chairs and posters. Are Mr. Kenmochi's chairs stored in such places?

Matsumoto There may be museums that have collections of commercial products, though. Unlike posters, furniture and other products are three-dimensional objects, so they take up a lot of space. It is really difficult to leave a legacy of furniture. I think other offices also face difficulties.

― Other well-known pieces of furniture include the "Rattan Chair" from the Hotel New Japan.

Matsumoto That rattan furniture has a three-dimensional shape, so it's a lot of work to draw it up and weave it. It takes one person to weave it, but it is made of a horizontal and vertical mesh, with a single vertical line running from top to bottom. There used to be three craftsmen in Japan who could make this, but now there is only one. We are now discussing how to preserve this technique.

A small design museum with one's own residence

― That is also an archive that must be bequeathed to the future. I would like to ask you about the interiors, you said you were working on the decoration at the time, do you still have any drawings of this work?

Matsumoto I also have interior drawings on the ground floor of my house. I haven't digitised them yet, and the first floor is almost a storeroom. I live on the second floor, and the third floor is a hall large enough to hold workshops, where I also keep my original chairs and so on.

― Are the drawings in paper form, or are they rounded up?

Matsumoto No, it is folded up and placed on the floor, but it is tracing paper, so it is becoming tattered. It is in such a state that if you touch it just a little bit, it will rip apart.

― What will you do about that in the future?

Matsumoto There is nothing we can do. To digitalise it, we have to take pictures with a very large machine, and I think it would cost quite a lot of money.

In terms of interiors at the time, for example, when the Kasumigaseki Building, which became the tallest building in Japan, was built in 1968, we designed the interior of TOKYO KAIKAN on its 36th floor. To prevent fires, steel plates were used for the pillars of the building and painted on top of them. The interior walls also had to be made of materials that would not burn, so we thought a lot about things like earth and mud, but in the end we decided to use bronze boards with textures etched into them. Bronze was cheap when I first got a quote, but then the Vietnam War started, so I rushed to call the manufacturer and got all the materials I needed. Sure enough, the price went up immediately. I remember jokingly telling the manager of the Tokyo Kaikan that if sales fell and you couldn't pay everyone's salaries, you could remove these panels one by one and supply them.

― What is the current state of TOKYO KAIKAN?

Matsumoto I don't know about now, but when I went to a party to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the building's construction, half of the bronze walls were gone. The space was also home to a large screen made of bronze squares by sculptor Ms. Aiko Miyawaki at the time. It was beautiful to see the view of the building opposite in that piece.

― Going back to the archive, does Mr. Kenmochi's archive still contain sketches and idea notes as well as drawings?

Matsumoto Most of the sketches and idea notes have gone somewhere, but we have some. I think they are in the storeroom, but they are not properly organised as to which project they are.

― Are there any contracts from your work, or any sort of memorandum exchanges, that are still there?

Matsumoto I have bound the contracts since I became Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates, but I don't think anything before that has survived.

― Do you have any photographs of the site, or photographs to document when the mock-up was completed?

Matsumoto The photos are also kept on the ground floor of my house. They are not organised. That room is half-underground and humid, so I don't really want to keep them there. After Kenmochi passed away, the photographer Mr. Yasuhiro Ishimoto gave me all the original negatives and positives films of the interior and other photographs he had taken. I thought it was such an important thing, but perhaps for him it was just a connection with Kenmochi, and he didn't think of them as his own work. Otherwise, I don't think he would have entrusted me with such important things.

Later, when we produced a collection of Kenmochi's posthumous works ("Kenmochi Isamu no sekai", 1 volume, 5 parts, limited to 1000 copies, Kawade Shobo ShinSha, 1975), most of the buildings were still in existence, and Mr. Ishimoto took photographs of these as well, which he gave to me. I have that at home too, but I am wondering what to do with it. Both he and his wife have passed away, and there is an his museum ("Ishimoto Yasuhiro Photo Center") in Kochi, isn't there? If that is where they want it, I would like to give it to them.

He had a strong obsession with colours, materials and textures

― Your home has become one design museum. I would like to move on to another question. Mr. Kenmochi passed away suddenly and the office was then taken over and run by Mr. Matsumoto. Does the fact that you inherited the name Kenmochi mean that you are still carrying on Mr. Kenmochi's design style and ideas?

Matsumoto That is a difficult question. One time, a client I have known for a long time said to me, when I was working on an interior, "Mr. Matsumoto, your use of colour is a bit different from your predecessors". "Would you prefer the Kenmochi’s style?" When I asked him, he said, "No, I don't think so, you should use the colours of the Mr. Matsumoto’s style".

Kenmochi had a unique use of colour. It was a colour I would not have chosen, but I did not dislike it. For example, when he used yellow, he would say "bitter yellow". It has a green in it, although only slightly. With red, he chose a colour with a little bit of blue in it, not vermillion red. I gradually became aware of the colours Kenmochi would choose, so I made colour samples by cutting paper to the right size and painting it with poster colours, and handed them out to manufacturers, and if he said "bitter yellow", I would bring them out and decide on the colour.

― The colours of the carpets in the "Kyoto International Conference Center" are unique, and the colour combinations of the furniture fabrics are also interesting.

Matsumoto Three types of green are used in this "Kyoto International Conference Center", but instead of the colour of grass, the motif is the colour of moss. According to Kenmochi, "The colour of moss changes with the seasons". In truth, four types are needed because of the four seasons, but he chose three different colours of moss - early spring, rainy season and summer - because in winter they look withered. For the carpets, we asked Kawashima Selkon Textiles to do the colouring many times. The unique colour of this kenmochi was so good that a Graphic designer Mr. Kohei Sugiura later even designed a case to hold the colour samples, which were then sold. At the time, that seemed to sell rather well.

― Did Mr. Kenmochi incorporate sensory elements into his design ideas and expressions, such as the bitter yellow, the colour of the changing seasons of moss?

Matsumoto I think so. He always had that kind of image of colour in his mind. He was also very picky about materials and textures. I think that was natural for an interior designer.

― The interior plays the role of connecting the building and the people, doesn't it?

Matsumoto That's right. In some cases, the inside and outside materials of the architecture are the same, so for example, in the case of a cool, inorganic concrete space, I created a chair with a soft fabric surround for the human seat.

― Were there many material samples in the office at the time?

Matsumoto There were many of them. At a certain point, I started to get a general idea of what Kenmochi always used, so I organised them like colour sample. "I have that one, I have this one, which one would you like? " Instead of saying to him, when he said "that one", I said "yes" so that I could give it to him.

― In terms of products, the design of the Container for "Yakult" is world-famous. It is so recognisable that if you look at the shape of that container, you know it is Yakult. Is it some kind of rational form that that one has remained amongst similar products?

Matsumoto We initially aimed for something like a milk bottle. We don't know who designed milk bottles, but they are very functional. In this way, We wanted to design objects that are widely integrated into our daily lives, even though we don't know who designed them. The same is true of the Kikkoman soy sauce bottles designed by Mr. Kenji Ekuan of GK. Anyone who sees it can tell from the shape and design that it is a kikkoman soy sauce bottle. I think that the more anonymous a design is, the longer it will last.

The difficult thing with Yakult was to change the material from glass to plastic, but the plastic made the bottles about one-tenth the thickness of the glass, making them smaller and thinner. However, the content was to be the same and the production line was to be the same as before, so that shape was inevitably created as we designed it to fit the height and width of the filling machine. Later, when it was decided to collect and recycle the containers, we were asked to think of something that could be used with the melted plastic, and after much thought, we designed a rack to arrange the containers.

First meeting with Isamu Kenmochi

― When did you first meet Mr. Kenmochi?

Matsumoto We first met when I joined the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute. I wanted to work in an architectural office after I left university, but I couldn't find a job, and the head of the department, Mr. Seiji Tsujii, who was worried about me, introduced me to the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute, which had a lot of design books and magazines and paid me a salary. When I went to visit, I was told that the departmental examinations were to be held that day, so I told them that I had not come here to join, but just to have a look, and they told me that I would have an interview in the afternoon. I later found out that Kenmochi, who was head of the design department at the time, was looking for someone with a background in architecture and had ordered my drawings and CV in advance. In other words, it was decided from the start that I would be hired.

When I first met Kenmochi, I thought that I didn't want to work with such a brash bastard, but he seemed to like me a lot. He had just returned from his first visit to the USA and was wearing a fluttering nylon shirt and bow tie, a type of clothing not seen in Japan at the time. In fact, Eames and George Nelson all wore bow ties, but Kenmochi later told me that it was good because it didn't hang down like a tie when he was drawing.

― What kind of work did you do at the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute?

Matsumoto My main task was to make knock-down furniture. Jobs came in rapid succession, such as designing booths for exhibitions and foreign trade fairs. The biggest job was at the International Design Exposition in Sweden in 1955. The offer for the job came one evening in December 1954. There were only seven months to go before the exhibition. I was told by Mr. Kenzo Tange that I would meet him the next day and that I should have it ready by then, so I thought about it overnight and drew the plans. That work was an opportunity for Kenmochi to incorporate my opinions and ideas in many ways.

I was at the Industrial Arts and Crafts Research Institute for four years, but Kenmochi left in the second year, in June 1955, to set up his own office. He told me, "I'll call you when I can pay you", and until then he asked me to go and help him just at night. I would only go at night, so the other staff at the office called me the "night chief". There was quite a lot of work and I was on the last train every night.

Thoughts and determination when taking over the office

― You were prospective as a partner. Later, when Mr. Kenmochi passed away, there were two paths: one was to continue the Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates, and the other was to make it the Tetsuo Matsumoto Design Associates. Why did you choose the former?

Matsumoto At some point, Kenmochi started suffering from depression, and I knew that he never wanted people to know about it, so Kenmochi's wife, myself and my wife, who worked in the office, dealt with it and kept quiet because we didn't want the office staff to worry about it either. As much as possible, I looked after him so that he would not be left alone, but he passed away on the day of the opening party of the "Keio Plaza Hotel" in July 1971.

His eldest son, Ryou, was 33 years old at the time and a graduate of architect Mr. Yoshichika Uchida's laboratory, where he also had his own office. However, the year after Kenmochi's passing, he was killed in a car accident while on an inspection trip in Austria. I think he had some ideas about the future of the office. I thought it would be better to close the office. However, I received many requests from various architects, including Mr. Kunio Maekawa and Mr. Yoshichika Uchida, both of whom I have known since the Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates, who said that they didn't want the office to disappear and that they wanted it to continue. They said, "Matsumoto has no choice but to do it". I had a lot of worries and thought about it, but I couldn't say "I can't do it" after being told that much. I thought it was my mission and decided to continue. But it was not good to keep the name Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates without him, so I took Isamu's name and changed it to Kenmochi Design Associates.

― So that's how you decided to continue. Did you have any kind of strategy as you made the big change in direction from Isamu Kenmochi's personal office?

Matsumoto At the time, we were desperate to move things where we could. Everyone had to eat. That was all I could think about.

― After that, your work expanded to include a wide variety of areas, such as vehicle design. I knew that designer Mr. Kazuo Kimura was designing Shinkansen, but I was reminded once again that you are also doing a lot of different things at Kenmochi Design Associates.

Matsumoto I became involved in Shinkansen and train design when I wrote a lot of complaints in "SD" (KAJIMA INSTITUTE PUBLISHING) about how uncomfortable the Series 0 Shinkansen were, even though the theme was ergonomics. One day, Mr. Jiro Kohara, a professor at Chiba University, read that article and came to visit me at the office. At the time, it was the era of the former Japanese National Railways and Mr. Kobara was chairman of the committee of the Japan Association of Rolling Stock Industries (JARi). As we talked about various things, it became an opportunity for me to be invited to join the research committee and I became a member. There was also a vehicle design office, and together with Mr. Kazuo Kimura, a designer at Nissan Motor, and Mr. Masamichi Tezeni, a professor emeritus at Tokai University who was also from Nissan Motor's design department, we formed a group called the Transportation Design Organization (TDO). Then, as a team, we worked on a project to design rolling stock for the national railways.

Archive since becoming the Kenmochi Design Associates

― What is the current state of the documents, drawings and models that have been kept since you became the Kenmochi Design Associates?

Matsumoto That is more problematic. In recent years, drawings and photographs have been digitised, so everything is still there, but it is not very well organised. Models and prototypes are also not organised, and I can't find the plaster casts I presented at Yakult because they've gone somewhere.

― What are your thoughts on archiving, given the current generational shift in designers and architects in Japan? I think architecture is still good, but the problem is in the industrial and product fields.

Matsumoto I think this is a very difficult problem. Especially in product design, for example, when working with manufacturers, it is no longer possible for a design office to own the product.

― Nowadays, if you ask, you can find out when the drawings and sketches were made and what they look like, but if you were to leave, I think the staff at the office would be in trouble. How many people are working in the office now?

Matsumoto Excluding myself and my chief of staff, we have about 16 people. At one time there were almost 20 people. During Kenmochi's time there were very few, but since my time, after a certain level of development, people have started to say they want to quit and go off on their own. In such cases, I try to support them as much as possible by teaching them how to survive, such as the know-how of signing a contract with a company and royalties. I think that's how I'll be worrying about all sorts of things until the day I die.

But everyone has done so well that now I don't have much to worry about anymore, so I say, "I'm quitting", but everyone says, "The director has to be Matsumoto". In fact, I think they can do without me even if I quit at any time.

― You have all the drawings and other materials at home, so isn't that also a concern for you?

Matsumoto Everyone in the office knows that the materials are at my home. They are all busy every day, so I don't think it would be good to tell them now, so I think I'll let the next, next generation think about that issue. I think that's the best thing I can do.

― It might be better for the generation that has never experienced those days to sort it out, so they can actually pick it up and look at it, so they can learn from it. Thank you very much for your time today.

Chair developed from a design for the " TOTSUKA COUNTRY CLUB". Commercialised by TENDO.

(Photographed at Kenmochi Design Associates).

Enquiry:

For questions about Isamu Kenmochi Design Associates and the Kenmochi Design Associates design archive, please contact the NPO Platform for Architectural Thinking (https://npo-plat.org).