Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

University, Museum & Organization

Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

Date: 9 July 2019, 13:30 - 15:30

Location: Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

Interviewees: Mikihiro Yamazaki (Director, Research Institute, for Architectural Archives / Professor, Kanazawa Institute of Technology),

Koji Sato (Researcher, Research Institute, for Architectural Archives)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki and Akiko Wakui

Author: Akiko Wakui

Description

Description

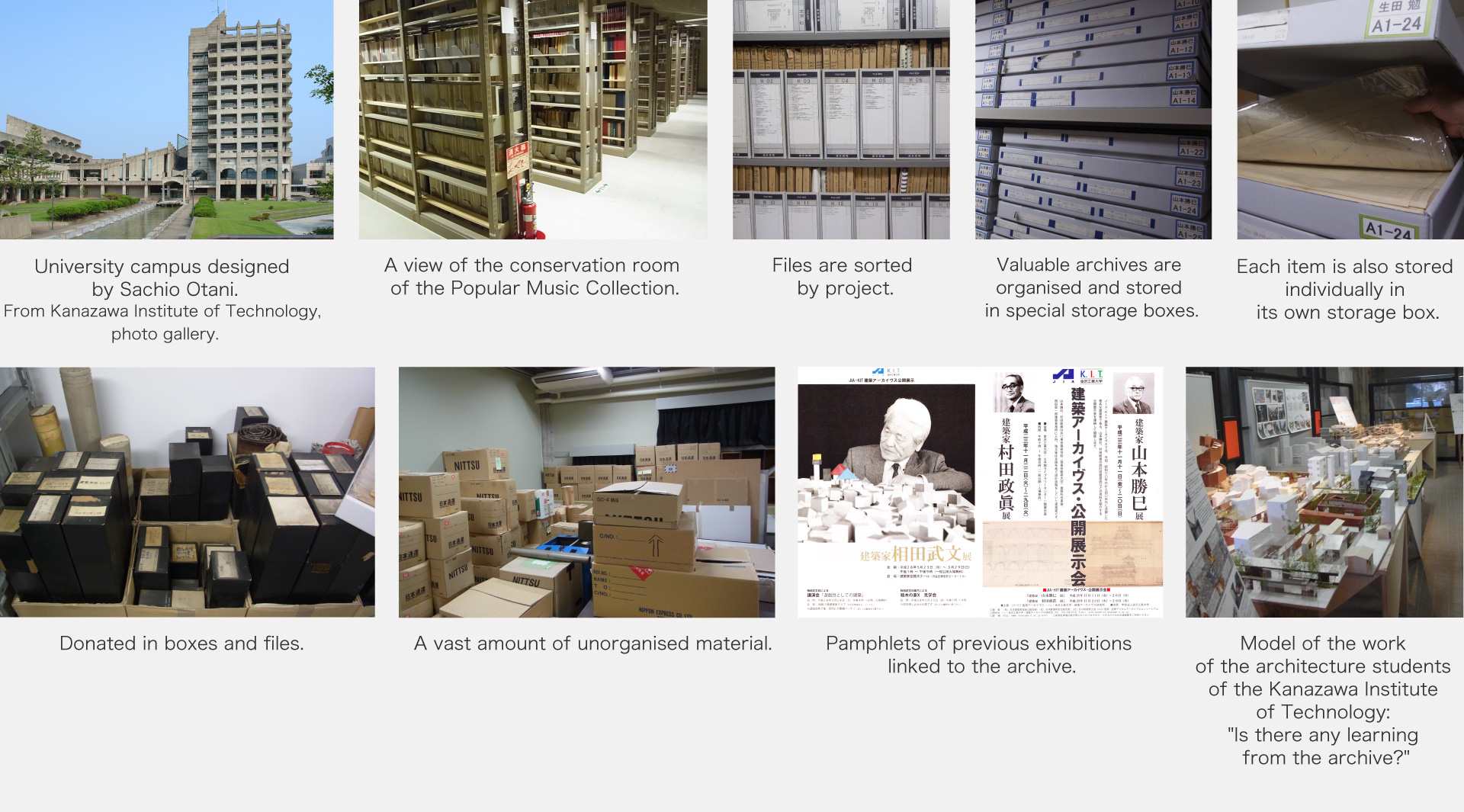

Research Institute, for Architectural Archives at the Kanazawa Institute of Technology (KIT) was established in 2007 to house the archives of the JIA-KIT Archives, a joint initiative of the Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) and the Kanazawa Institute of Technology (KIT). Since then, the Institute has been collecting, preserving, organising and researching architecture-related materials for the past 12 years. During my last visit in January 2017, I was given an overview of the Institute and had the opportunity to see the archives vaults dotted around the campus. We were overwhelmed by the sheer volume of material, some of which was carefully organised and stored, while others were covered in cardboard boxes, many of which had not yet reached that stage of organisation. How do they receive and manage these mountains of material? How do they manage to find the manpower and space to organise them? We wondered if it would not be possible for those who send archives to reduce their workload a little. In order to find out more about this situation, we visited the Research Institute, for Architectural Archives again and asked about the situation on the ground, from the reception of the archives to their organisation and use.

Interview

Interview

We scoop up what someone else has worked hard to leave behind and leave it behind.

That's why we try to keep it going for as long and as thin as possible.

Managing large volumes of material requires a step-by-step approach to organization.

― During our visit in January last year, we heard a talk from Mr. Chiku Kakugyo about the overall approach of the Research Institute, for Architectural Archives. This time, we would like to hear about specific ways of organising the archives and future challenges.

Yamazaki I took over the role of Director of the Institute of Architectural Archives in 2007, ten years after its foundation. Chiku is still involved as an advisor. As for the organisation of the archives, our full-time researcher Sato is involved in this on a day-to-day basis, so he will talk about the specifics and I will try to supplement him.

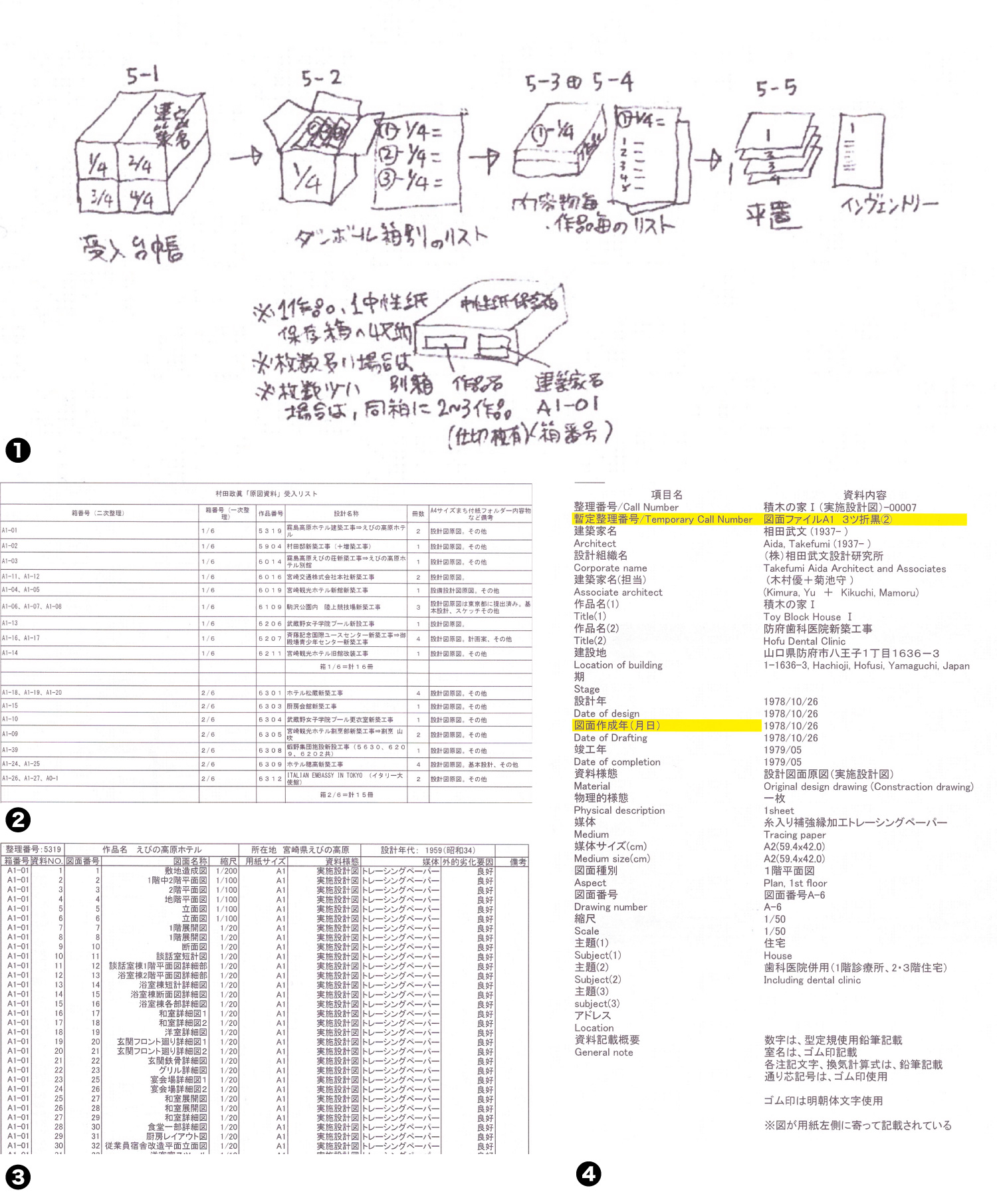

Sato The general flow of my day-to-day work is shown here (the following diagram). The first thing we do as a temporary arrangement is to create a register of incoming materials. At this stage, we write the box number of each cardboard box that arrives, and create a file with the storage location, the name of the donor, the number of cardboard boxes and the date of receipt. We then send this ledger, together with photographs of the cardboard boxes, to the donors to report that we have received them correctly. Whenever possible, we do this on the day of receipt.

The next stage is to open the cardboard boxes we have accepted. The cardboard boxes contain drawing files, tubes, etc. Each of them is given a box number and the information on the contents of each box is recorded and listed. Up to this point, this is the work we do on a daily basis.

Yamazaki At this stage, we do not check the contents of the boxes against the actual contents, as this list will ensure that we can respond to any external enquiries about the availability of the material. Beyond that, when our students use the materials for research, or when outside researchers come to look at them, we ask them to sort them out as well. This means that items that are in demand will be sorted out, while those that are not will remain in the same condition. II also ask students in my seminar and in other research seminars to organise the material for me.

Sato At that time, we check the contents of the file or tube and extract the name of the work, the date, the name of the person in charge and the type of drawing on the drawing to make a list. Furthermore, they are classified and listed by work and transferred from cardboard boxes to neutral paper storage boxes. At this point, a new serial number, prefixed by the size of the neutral paper storage box, is added to the inventory. At the end of the process, an inventory (a list of each item of material) is drawn up.

1. A diagram showing the stages from receipt of materials to sorting them into individual items.

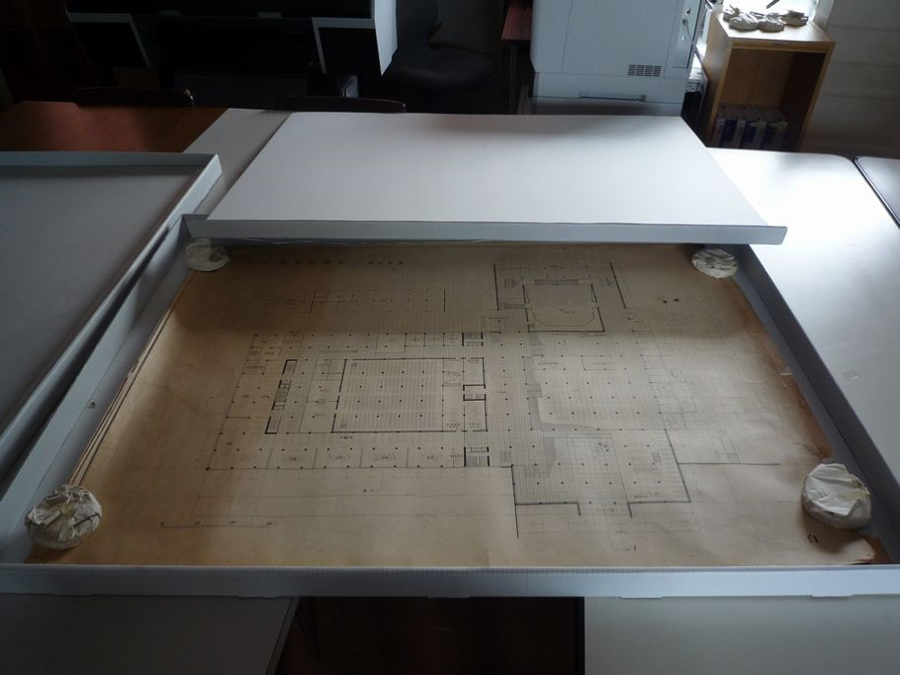

2. List of materials classified according to their contents after secondary sorting (corresponds to 5-3 in the figure).

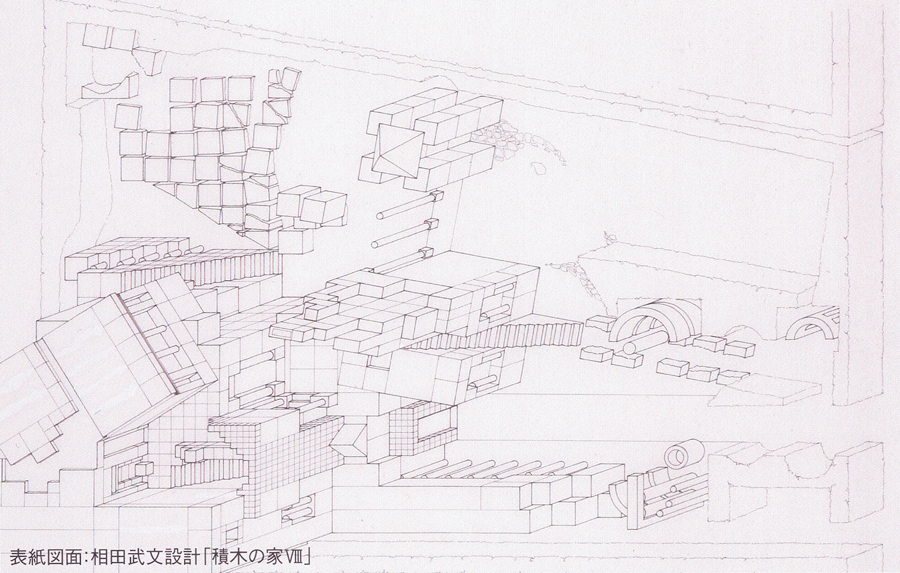

3. In addition, a list of materials classified by work (corresponding to 5-4 in the diagram).

4. Inventory created at the end of the consolidation process.

― You must have had a lot of work to do to develop this method of organisation. Did Mr. Sato study archiving before?

Sato No, I don't. I used to work in a architectural design office. So I was brought in because I knew the flow of design and construction, and I could draw by hand and in CAD, so I was the right person for the job. Initially, it was a case of opening one box at a time and sorting through one item at a time, but I have found through practice that I need to have a complete picture of the material before I can get to the final sorting. This is because no single piece of work is organised in a single cardboard box, and we can only find out by opening them all. For example, there is a list of drawing numbers from 1 to 50 for a single work. It is only when all the cardboard boxes are opened and sorted that we finally find out that there are 50 drawings for that work. If we had received donations of specific works, we could have sorted them one by one from the beginning, because the total number of works was not so large. However, this was not possible, because we sometimes received dozens of boxes, and sometimes as many as 100 boxes, without sorting.

― Sometimes the name of the work and the name of the project are different, aren't they? Is it possible to tell them apart from the beginning?

Sato At the stage of making the first list, we do not check the contents against each other, so we cannot identify them. When we create the inventory, we use the name of the work as it was published, work 1, and the name of the project as work 2.

Yamazaki Even if it's a famous building, the name of the project alone doesn't tell us anything. That's why we have a separate list of project and work names, which we have to analyse. So, when I make the first list, I record the names as they appear on the drawings or on the bags outside.

5. Drawings stored in a neutral paper storage box.

Pre-acceptance field checks to ascertain the actual situation

― How do you check what and how much material is available before you accept it?

Sato We try to visit the site as much as possible to see how much of the material is stored and in what condition. We respect the will of the donor and try to accept as much as we can, so if the architect himself chooses what he wants to donate, that is very helpful. However, when the person has died, it is not uncommon for the family and the pupil to have no idea what to leave. Sometimes they send us the items they have found, but sometimes they send us everything, so it is very difficult to find storage space for them. So we go to the site and see what they have, and ask them to donate only what they want to keep.

If it is not possible to carry out a site visit, we will also ask you to check if there is a list of documents available beforehand, or to send us photographs of the documents.

Yamazaki There was an architect who kept a collection of drawings, books and hobbies in the basement of his house and architectural design office. He once showed me around the storeroom and told me directly that he wanted to keep this and that drawing. We were able to get a rough idea of the volume on the spot and were able to move quickly to the stage of getting a quote from the transport company.

In the case of the deceased person, the architectural design office that also served as his home was left as it was before his death, and neither the family nor his apprentice could grasp the extent of the donation. At that time, we had a list of materials that had been made by a former member of staff, but the drawings were still on the shelf, so we couldn't check them against the real thing, and we couldn't predict the actual volume. So we had to go back and forth for a long time until we got the package ready.

Recently, after his death, his wife and a former member of staff from his office, who had kept and organised the material in his home, came to us for advice on the donation. Since spring last year, we have been exchanging information with them, asking them to visit our Institute to see the state of conservation in person, and us to visit the site to check the actual items.

― How long do such exchanges take per case?

Sato It's about one or two years.

― That's a long time. On the other hand, in which cases is it not possible to check the site?

Yamazaki This is when there is no time to spare. If you are in a hurry, we may ask you to take photographs of the material and send them to us to see if we can accept the volume. For example, he was about to move out of his office and if he didn't make it by then, everything would be destroyed. As we could not come to the office at short notice, we asked them to send us the items as an emergency evacuation.

― When you do that, you get all kinds of stuff, so it can be quite a lot. How many cardboard boxes do you receive at the most?

Sato We once received about 100 boxes.

6. Storage room with donated materials.

Sorting out what to keep and what to get rid of

― You say that you try to follow the donor's wishes as much as possible, but are there any items that you do not accept?

Yamazaki Basically, we do not accept books. The books that are not in our university library are kept in the library, and those that are necessary for the archive, such as design works and collections of works, are kept, but the others are disposed of. Rather than not accepting them, we often ask people to send us their books together with materials, with the prior consent of the library that they will be disposed of.

Sato The most common are the magazines in which his work has been published.

Yamazaki We do not accept digital data. The aim of the Institute is to preserve hand-drawn drawings in the face of their loss, so we basically focus on sketches and other hand-drawn drawings and related materials. We sometimes keep post-digital items together with hand-painted ones, but there are a number of problems that arise when we try this, so for now our policy is not to include them.

― What about architectural photography?

Yamazaki We've kept some construction photos in our archives. But we do not collect architectural photographs, because the copyright of the photographs is very difficult. When we need architectural photographs, for example to display drawings at exhibitions, we work with a digital archives organisation called DAAS.

― Are there many cases where you accept more than just drawings?

Yamazaki We often receive not only drawings but also private things. If the person has died and we don't know their intentions and we receive all the material, we will generally accept it if we can see a portrait of the person, and we may display it with the drawings at an exhibition. On the other hand, if the person wishes to leave only this and that, we will keep them within the scope of the donation, and will not ask the person to donate anything else.

― Will hand-drawn drawings be digitised?

Sato We do not convert them into digital data from the outset, although our students may copy or photograph them for use in their theses, for exhibitions, or in response to requests from external visitors. As I told you earlier, we can only make an inventory after a stage, so if we make digital data before that, we don't know where it is and what it is.

Yamazaki When we set up the institute, our first priority was to create a digital database and make it available to the public at any time, so that donating to the regions would not be a disadvantage, but when we started, we realized that we could not do it all at once.

What donors need to do before they donate

― It's difficult to find the budget, human resources and space for the project, so I think it's important for the donor to prepare in advance in order to reduce the burden on the recipient. What are some of the things that donors could do to help?

Sato Firstly, it would be helpful if the donors themselves could make a selection of what they would like to keep and what they would not. If the person dies without communicating his or her wishes, both the bereaved family and the pupil are emotionally inclined to leave everything behind. But we can't take it all in ourselves, because we need so much space, and if the bereaved don't know anything about architecture, we don't know what's important to them. It would be a pain for everyone who is left behind.

Yamazaki Some of the things that are thrown away may be of value to another person, so it's best to leave everything behind, but if there are too many, even the most important things can get buried. So it would be very helpful if you could sort out what you definitely want to keep and what you want to keep if you can.

Also, at the end of a project in any architectural design office, only the important things are left and the unnecessary things are disposed of, and the next job is started. This is how we have been organising the material day by day, and this is what remains at the end of the day, and this is how we end up keeping it. The work flow itself is archiving, so we would be most grateful if you could bring the items to us in the same condition in which you have organised them at work, rather than having to repack them in new boxes.

Sato It is also useful for archiving if there is a good record of the work. The blistering work ledger contains all the clues to who did what, when and where, including the project name, location, design period, construction period, person in charge who designed the project, general contractor who constructed the project, design control amount and construction contract amount.

― What is the minimum you would like us to do when we send you things?

Sato It would be helpful if you could make it clear what is in each cardboard box. If it is possible, a list of the contents of each box would be greatly appreciated, so that we can quickly create an inventory.

Space availability and cost effectiveness issues

― Twelve years on from the launch of the Institute, what are the biggest problems you have found so far?

Yamazaki It's still a question of space. The more we organise, the more capacity we have, and the more space we have to make each time. If we were to open the contents and replace them in a neutral paper storage box, it would triple the amount of cardboard.

At the time of setting up, we expected that there would be a certain amount of headway, because some important architects had already died, some things had already been thrown away, and the move to CAD would mean that new hand-drawn drawings would never be produced again. In fact, the volume has not exploded in the last 12 years and we have not run out of space, but we still have to negotiate with universities all the time. Naturally, we are expected to deliver results commensurate with the space we provide, but archives do not directly generate money. We have managed to find space for it, because if we can build up a certain volume and make it more valuable, it will be a good advertisement for the university.

― Is there any funding from the JIA?

Yamazaki All the costs of organising the materials are borne by the university. So we have to do everything we can to make it as inexpensive as possible. That's why we don't sort them all out, our first priority is to evacuate them so that they can't be thrown away. I think that the things that are left that we haven't been able to get rid of are either by luck or because someone else has worked hard to leave them behind, so I'm trying to think of a way to keep them going for a long, long time so that we can at least scoop them up and leave them behind.

― Have you had any problems in the past?

Yamazaki At the moment we don't have any. We have a donation contract first and then we start organising, so there is no need to get into trouble. However, if the donation is made as a deposit, the scope of the donation will be decided and contracted after the arrangement is made, so a deadline must be set before the arrangement is made. Then we cannot accept anything that is too much. That's why we have a donation contract and leave it to us to sort out the rest, which is why we are able to do what we do now.

Sato In the end, I think this is due to the fact that we have built up a relationship of trust by having people come and see the storage area and check the site beforehand, so that we can both go back and forth.

7. Drawings of Takefumi Aida's 'Toy Block House VIII', which have already been sorted out.

How archives are used and what the future holds

― We were told that these archives are used not only for papers but also for exhibitions and teaching materials. I think that is one of the outcomes that universities are looking for, but what is the current situation?

Yamazaki We don't do a lot of exhibitions, so we don't have that much PR yet. As a teaching aid, we use it for practical work making drawings and models. Some students also suggest that design drawings can be traced and used as a reference for drafting. However, since it is the work of an architect from a long time ago, students today can learn how to draw, but the design is not the same as today's trends. So I don't think that we have been able to use them directly as teaching materials yet. However, I believe that by continuing to have the archives, they will eventually be of value. This is because the "Kōgaku no Akebono", a collection of rare books that my advisor, Mr. Chiku, has been collecting for many years, has finally become known throughout the country after more than 30 years of touring exhibitions.

― What is the main aim of the university's archiving initiative?

Yamazaki Some universities are research-orientated and some are education-orientated, but as we are an education-oriented university, our main aim is to use the materials entrusted to us for educational as well as research purposes. For the students, just to actually see the drawings and documents that they will have to deal with in the future is a living teaching tool, so we give back to them as an education, including making models.

Sato A picture is worth a thousand words, and if students make a careful list of all the documents they need to organize, it will help them when they write their graduation thesis, and when they get a job, they will know that they need so many documents, which is a great learning experience. So even when we get enquiries from outside, we tell them to come and have a look here first.

Yamazaki It is very important to have one resident person in the institute. Research can be carried out concurrently with teaching, but there must always be a point of contact who can respond immediately to enquiries, and who can also be trusted by donors. As a depositor, their biggest worry is that if they donate it, they will never be able to get it out again.

― Did any of the students who were helping to organise want to study archiving?

Yamazaki In the past, we've had students who go on to postgraduate study help with archiving, but now the economy is good and there are no job opportunities, so no one wants to make a living doing this. As an archivist in a large organisation, this might be different if the work of organising the company's materials on a daily basis were to be done in a conducive environment. However, it is difficult for universities to do so, so that is something we would expect from the private sector.

Sato In major companies such as general contractors, there are people in the administration department who make company histories and in the field, and there is a manual that defines what should be kept as a minimum. Private architectural design firms don't have that luxury because they have to move on as soon as one job is finished, and different people have different ways of organising things.

Yamazaki I hope that the students who study with us, although he doesn't have to be an expert, will see the importance of this kind of behind-the-scenes work, and when they start working in architectural design offices, they will take the initiative to organize the archives and donate them to the university in the future, and become a link between the company and the university.

― I think you are right. Thank you very much for sharing your valuable stories about the field of archiving with us today. It was clear to me that it is very important for people to be clear about their intentions for the archives and to be able to see what they have packed in the cardboard boxes when they send the material so that it does not get buried.

Enquiry:

Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

https://wwwr.kanazawa-it.ac.jp/archi

Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

Chiku Kakugyo

Date: 23 January 2017, 13:30 - 15:00

Location: Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

Interviewees: Chiku Kakugyo(Advisor, Research Institute, for Architectural Archives), Koji Sato (Researcher, Research Institute, for Architectural Archives)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki and Akiko Wakui

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Chiku Kakugyo

Doctor of Engineering, Professor at Kanazawa Institute of Technology

Director of the Library Centre, Advisor, Research Institute, for Architectural Archives

1971- Assistant, Lecturer, Assistant Professor and Professor at Kanazawa Institute of Technology

2007- Appointed as Director of JIA-KIT Architectural Archives and Director of the Research Institute, for Architectural Archives

2012- Appointed to the Management Committee of the National Archives of Modern Architecture

2014- Appointed to the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives Committee and to the Board of Directors of the specified non-profit corporation for the Inheritance of Architectural Culture

2017- Appointed advisor to the Research Institute, for Architectural Archives

1985-1991 Visiting researcher at MIT, International Trainees at the Library of Congress

1994-1995 Director of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Director of its Library

Description

Description

The Kanazawa Institute of Technology (KIT), located in Nonoichi, adjacent to Kanazawa City in Ishikawa Prefecture, is recognised for its high educational value-added and supportive approach to independent student learning. The Ougigaoka campus, which we visited, was designed by architect Sachio Otani (1924 - 2013), known for his work on the Kyoto International Conference Hall and other buildings, and the new campus has been extended in line with the times and technological developments. According to Mr. Chiku Kakugyo, advisor to the University's Research Institute, for Architectural Archives (Director of the Institute at the time of this interview), "The University is very active in supporting extracurricular activities as well as classes, and has excellent facilities such as the Self-Development Centre, Innovation and Design Studio and Entrepreneurs' Lab. As a result, students spend a lot of time at the university and can study 300 days a year". The library is famous not only for its books and journals, but also for its PMC (Popular Music Collection), one of the most extensive archives of LP records in Japan. The library is open not only to students but also to the general public with certain procedures.

Mr. Chiku, a university library professional, is one of the few people in Japan who has been involved in the development of this environment. After studying library science at the Library of Congress in the United States, Mr. Chiku planned a comprehensive library center for the Kanazawa Institute of Technology. The center also has a collection of rare books called the "Kōgaku no Akebono", which were collected through Mr. Chiku's network. These include Alberti's "Ten Books on Architecture" and Palladio's "Four Books on Architecture", both of which are coveted by architects, as well as famous works by giants of science such as Galileo, Newton, Faraday and Darwin, who changed the course of natural science and engineering. As the digitalisation of information accelerates, these rare editions are a valuable cultural heritage that allows us to experience first-hand the greatness of human creativity.

The JIA-KIT Architectural Archives is a collaboration between the Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) and the Kanazawa Institute of Technology (KIT) that began in 2007. The Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, which is responsible for the material, is one of the few institutes of higher learning in Japan established with the aim of collecting, preserving, organising, researching, publishing, using and passing on material relating to architecture.

Interview

Interview

The "Research Institute, for Architectural Archives" is one of the few valuable research institutions in Japan.

Background to the establishment of the Institute of Architectural Archives

― Japanese architecture has attracted attention from all over the world, including many Pritzker Architecture Prize winners, the Nobel Prize for architecture. However, there is no single institution in the country that collects, preserves and studies these valuable archives in one place. In this context, the presence of the Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology is very valuable. First of all, could you tell us about the background to its establishment?

Chiku It is true that Japanese architecture has gained an international reputation. This is the result of many years of steady achievement. We believe that sketches, drawings and models, which document the process of creating an architecture, are valuable assets and that it is our important responsibility to pass them on to future generations. In Japan, however, the preservation and transmission of architectural archives is almost non-existent, and valuable materials are being lost and dispersed. Once something is lost, it cannot be regained. Especially before computers, drawings and sketches were "handwritten on paper" and had to be worked on as soon as possible.

So, as an emergency evacuation, the Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) and others decided that we had to do something about it. In 2007, the Japan Institute of Architects (JIA) and the Kanazawa Institute of Technology (KIT) joined forces to establish the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives, and at the same time, the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives was established as a center for the collection, preservation, organisation, research, publication, use and transmission of architectural materials.

― What kind of materials related to architecture do you collect and preserve?

Chiku The archive is divided into three main categories. The first is what we call the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives, which includes drawings and photographs by architects such as Mr. Takefumi Aida, Mr. Hiroshi Oe and Mr. Mayumi Miyawaki, as well as sketches by world-famous architects such as Mr. Louis Kahn, which were collected by Mr. Toshio Nakamura. The second is a collection of documents relating to historic buildings in Kanazawa, including drawings and photographs of the period. The third is KIT's own archive of architecture, including lecture notes and papers by Mr. Hideto Kishida, and research materials on modern and contemporary architecture in Kanazawa that the university has produced.

― What kind of material do you collect for the architect's archive? How do you select the architects for the archive?

Chiku They include original design drawings, sketches, models, structural calculations, facility plans, photographs, correspondence, notebooks, notes, slides, microfilm, contracts and books. Rather than selecting the architects, members of the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives committee meet to decide on the management policy, collection targets and to encourage JIA member architects to donate their work. After consultation with the architects, JIA-KIT Research Institute, for Architectural Archives and the architects have signed a contract to hold the valuable materials. The JIA established the specified non-profit corporation for the Inheritance of Architectural Culture (Representative Director: Mitsuru Senda) in 2014 in order to permanently plan and manage the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives, which includes the JIA-KIT Architectural Archives Committee.

― What are the expectations of the donating architects?

Chiku For them, it means that valuable materials are organised and stored according to certain rules. What is even more important is the desire to pass on these materials to future generations as living documents and to make them widely available for the development of architectural culture, rather than just storing them in a box. Our aim is to make architectural archiving an academic discipline and to establish it as such.

― How much material do you actually collect?

Chiku That's about 600,000 items. So far we have received material from 26 architects, architectural design offices and architectural associations. The main architects are Takefumi Aida (11 works), Kazumasa Yamashita (400 works), Kiyoshi Kawasaki and Azusa Kito (300 works each) and Masayuki Kurokawa (296 works) , for whom the collection includes original design drawings, sketches and photographs.

What is archiving of architectural documents?

― What exactly does archiving mean?

Chiku We need to consider many different aspects.

The first is to obtain information on the whereabouts and condition of architectural materials and to collect them in order of priority for conservation. In addition, materials that are expected to deteriorate are recorded digitally and made available to the public in digital format. At the same time, we are developing repair and storage techniques with the aim of preserving the originals for many years. The second is to create a system that allows everyone to access the vast amount of material, by organising it, converting it into data, and developing a common national search system. The third is to make our database on archives widely available through the internet, exhibitions and publishing activities, so that everyone can have access to and make use of architectural knowledge, and to increase its convenience.

And fourth, of course, is to find ways to use it in architectural education. The University has a wide range of programmes for architecture students. Fifthly, we would like to carry out measured surveys and photography of historical buildings and urban design, accumulate the records of these surveys, and develop an efficient storage system. The sixth is the storage and organisation of information and records relating to the architectural design process. And finally, we will use current digital technology to create three-dimensional data on a wide range of buildings and cityscapes, and to make effective use of this data.

― That's a task that requires a huge amount of effort and time.

Chiku Yes, it would be difficult for our institute to do everything on its own, but we think it is not impossible if different organisations work together in a network. In fact, it can be a challenge just to keep the vast amount of material that is sent to us in cardboard boxes in a proper condition. In addition, it takes an enormous amount of effort just to open a cardboard or drawing case, read through the drawings and documents one by one, and sort them by project. At the moment, Koji Sato, a full-time researcher at the Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, is leading the work, with the participation of students, but it is not easy.

― Since its inception, the Architectural Archives Institute has been organising exhibitions and lectures focusing on architects, using the JIA-KIT architectural archives. Last year there was also an exhibition by Mr. Takefumi Aida, known for his "Toy Block House" series. The brochure shows not only the works on display, but also a lecture by the architec himself and a tour of the actual work ("Toy Block House X"), which I think is a wonderful multi-faceted approach.

Chiku The archive is important, but what you get from the actual architecture and architects is even more valuable.

The current state of Japan's architectural archives

― In recent years, more than ever before, I feel that there is a growing awareness of the need to pass on things of historical value and cultural heritage. In terms of architecture, the collections of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris and the Museum of Modern Art in New York are well known, but as far as you know, what is the state of architectural archiving in Japan?

Chiku There are only a few organisations in Japan that systematically archive architectural materials, but in 2012 the National Archives of Modern Architecture was established in Yushima, Tokyo, under the jurisdiction of the Agency for Cultural Affairs. I am also a member of the Steering Committee, which is responsible for collecting information about architectural materials, collecting and storing materials, exhibiting and disseminating education, and conducting research.

― They also hold special exhibitions. Last year, I went to an exhibition called "How to Create with Everyone", which dealt with Takamasa Yoshizaka + Atelier U, and it was very informative and carefully structured with models, drawings and VTRs featuring people who knew Mr. Yoshizaka. In 2014, they also organised an exhibition called "Towards Architectural Archives".

Chiku That's exactly what makes archives so important. As I have said many times before, it is not enough just to store valuable materials. The goal of the archive is to organize them, reproduce them in a story that is relevant today, and make them accessible to a wide audience.

― You mentioned the National Archives of Modern Architecture, but what about the others?

Chiku The Togo Murano Archive at the Kyoto Institute of Technology Museum and Archives was established in 1996 when Mr. Murano's family donated over 50,000 drawings and other items to the museum. Mr. Hiroshi Matsukuma, a professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology, who is also an architectural historian, has been organising the archive and making it available to the public. Since 2000 he has also organised the "Togo Murano Architectural Drawing Exhibition" as part of his research and documentation. The museum originally housed art objects such as Art Nouveau posters, but Murano's archive is a valuable source of information about modern and contemporary Japanese architecture. Another example is the Digital Archives of Architecture and Space (DAAS), which makes use of digital technology. It is a consortium of major construction companies, architectural design offices and architectural organisations, of which I am a member of the steering committee, that collects and digitises photographs of outstanding architectural works, preserves them and makes them available on the website. The archives are not limited to photographs, but also include architectural drawings, images of outstanding buildings that are disappearing, and video interviews with famous architects. In short, it is a digital archive that organises, preserves and publishes valuable architectural material in digital form.

― How did you get interested in archiving in the first place?

Chiku I studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and my experience at the Library of Congress. American universities are open 24 hours a day and students are free to study at any time. I was very surprised by the difference between the Japanese universities.

In the United States, learning by yourself in the library is as important as lectures by professors. That's why every university puts a lot of effort into improving its library environment. However, when it comes to research, it is critically important to examine not only books, but also primary sources such as drawings, photographs, various archival documents and data, which are stored, accumulated and organised for use in archives. The MIT Museum maintained an archive of such material in various areas. In the United States, governments, companies and universities have set up archives. After MIT, I studied library science as an international trainee at the Library of Congress, which is not only the largest library in the world, but also a huge archive of cultural materials. There was also an architectural archive, which held a vast amount of survey and architect's material from the United States Department of the Interior's Historic American Building Survey (HABS).

So, in the United States, there is a well-established profession of archivists in various fields, and there are architectural archivists all over the country, and there is a society for them. The current architectural archivist for the Library of Congress is a Japanese woman. At KIT I am involved not only in architecture, but also in music (records, magazines, etc.) and the collection and preservation of rare and antique books. We would like to explore the possibilities of the library as an "accumulation of human knowledge" as well as an architectural archive.

To continue, Koji Sato, our full-time researcher, will explain how we store and organise our architectural archive.

Organisation and preservation of architectural archives

― You have a dedicated building for the collection of materials.

Sato The building was originally used for other purposes, but the University bought it to store the architectural archives and renovated it for use.

― How exactly are they stored and organised?

Sato As explained earlier by Chiku, the documents range from drawings, sketches, photographs and models. Architectural drawings and other documents are often handwritten on tracing paper, or blue prints made from photosensitive materials, and are often damaged or otherwise deteriorated. This is especially important if they have been stored rolled up, as they will tear or shatter just by being unfolded.

The first step is to carefully spread them out, classifying and organising them according to project and age. Then, if necessary, repairs are made and the final product is delivered in a neutral paper storage box. We have our own storage boxes, ranging in size from A2 to A0, which we use according to the size of the drawings. Organising it requires an enormous amount of effort and patience. After all, we have to read each drawing or sketch that we come across for the first time, relate it backwards and forwards, and organize it in an archive.

― Do you work alone now, Mr. Sato?

Sato I am the only one who works on a full-time basis, but fortunately we also have the participation of students from our architecture department. However, in order to be more efficient, we may need to expand our organisation and systems.

― How are the materials stored and used after they have been sorted out?

Sato Once we have a good idea of how to organise the archives, we organise exhibitions and lectures to give students and the general public the opportunity to get to know the archives. In addition, the students of the "Yumekobo Architectural Design Project" at the University develop their ability to express the world from two-dimensional to three-dimensional through the creation of models from drawings as part of the project, and at the same time use the project as a valuable teaching tool to learn about the design ideas and methods of their predecessors in architecture. Furthermore, reading and interpreting the drawings, which are also a record of the design process, and reconstructing the building while reliving the design process, seems to foster empathy for the architecture.

― I was very impressed with your very careful work. Thank you very much.

Enquiry:

Research Institute, for Architectural Archives, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

http://wwwr.kanazawa-it.ac.jp/archi/

Reference:

National Archives of Modern Architecture

http://nama.bunka.go.jp/

Digital Archives for Architectural Space

http://www.daas.jp/