Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Susumu Kitahara

Interior Designer

Interview: July 6, 2020, 13:30-15:00

Interview location: K.I.D. Associates, Inc.

Interviewed by: Susumu Kitahara, Hiroshi Hatanaka (H2O Design Associates)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

PROFILE

Profile

Susumu Kitahara

Interior Designer

1937 Born in Tokyo

1961 Graduated from the Department of Crafts, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Joined Tokyu Department Store and worked in the Tokyu Shirokiya Furniture Design Section.

1964 Joined Pacific House.

1966 Participated in the establishment of Form International and became chief designer.

1970 Established K.I.D. Associates (meaning Kitahara Interior Design) and became its representative.

2020 On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the company, he stopped what he was doing.

Description

Description

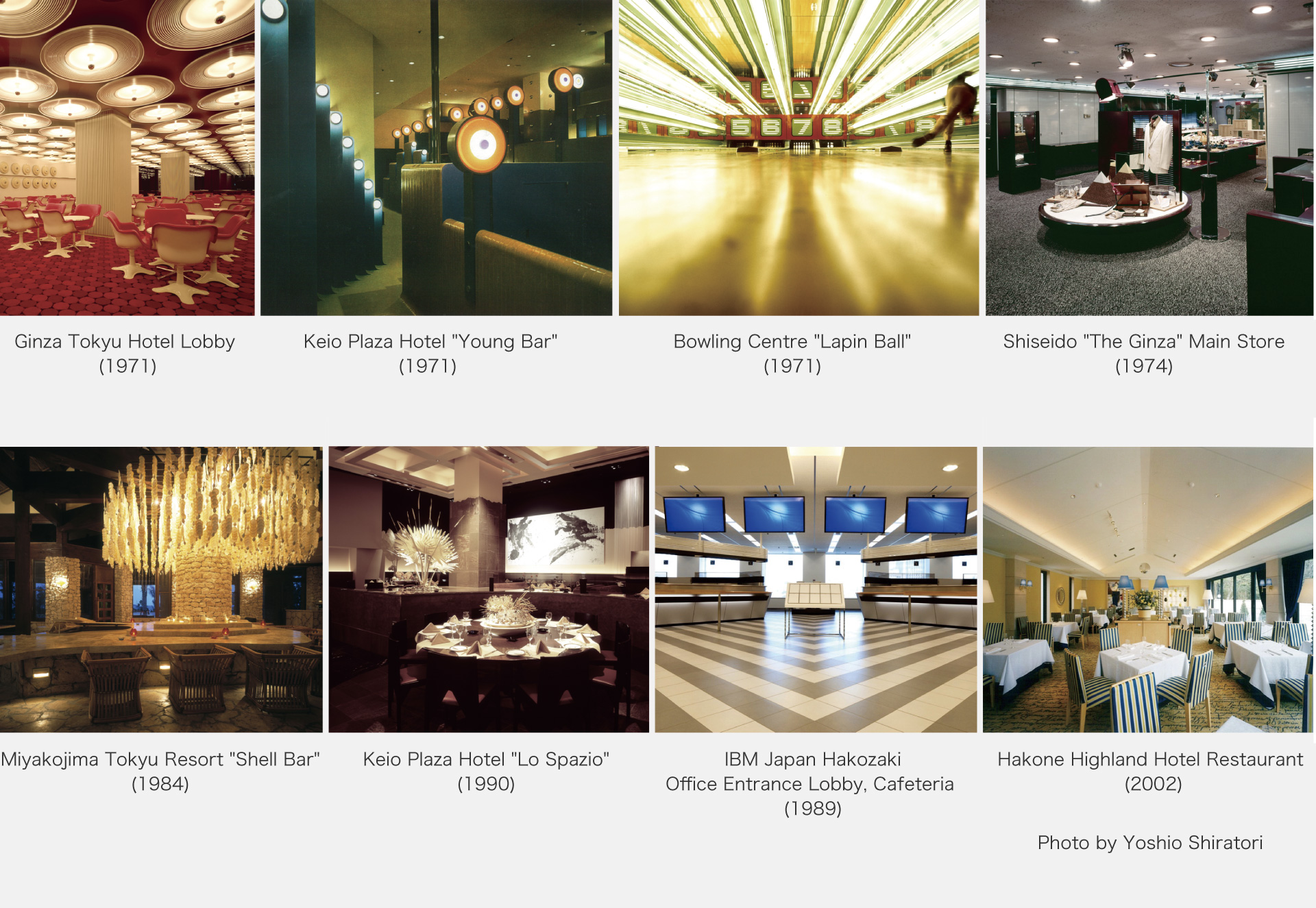

Susumu Kitahara is a leader of an early period in the history of interior design in post-war Japan that should not be forgotten. In the In the 1960s, Japan was aiming for an international level of design, and under the guidance of the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO), there was an urgent need to train ID designers to create products that could be sold abroad. Many of Kitahara's fellow students at the Tokyo University of the Arts went on to work for car manufacturers and consumer electronics companies, but Kitahara was the only one to take the plunge into interior design, a field where the term "interior design" was not even used yet. This was the start of his career, which is now regarded as unique. He worked at Pacific House, where he studied under the American architect Dale Keller, the chief design director. It was there that he was thoroughly drilled in what it means to have a functional and beautiful interior in the international style that symbolises a modern nation. This background, combined with the guidance of the then Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), led him to take part in major spatial projects such as first-class hotels and offices for foreign companies, which were the subject of spatial design at the time. Thus, at a young age, he was entrusted with big projects such as the Kasumigaseki Building Tokyo Kaikan, the Akasaka Tokyu Hotel, the Ginza Sony Building, and the Imperial Hotel.

Since the establishment of K.I.D Associates, he has designed over 120 spaces, including hotels such as the Young Bar at the Keio Plaza Hotel, office buildings, and shops. However, in the history of interior design in Japan, there has been a tendency to focus more on design as an expression of the individuality of domestic artists, and not much has been said about design with a high public profile. The spaces designed by Kitahara were considered to be a unique step in the interior design trend at the time, even though they were the mainstay of society.

Shiro Kuramata, in his analysis of Kitahara's book, cites his decision not to use his personal name as K.I.D. Associates when he became independent as an example of "a macro perspective rather than a micro one". However, K.I.D. has the name Kitahara hidden in it. The "heart" of K.I.D. is the pride that the face of expression should be anonymous, and that individuality should be hidden from the public. Without a perspective based on how to objectively respond to the demands of society, rather than a pursuit of authorship, Japanese interior design would never have been promoted to the global level.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Office/Showroom

IBM Japan, Hakone Sengoku Lodge (welfare facility, 1965), Fujisawa Plant (1967), Head Office Building Audio Room, Entrance Hall (1970), Yasu Plant Cafeteria, etc. (1974), Hakozaki Office Lobby, Cafeteria (1989), and other projects throughout Japan.

Fujie Textile showroom (1972), Fujie Shop "Heart Art" (1974).

Ricoh Showroom, Ginza (1977), Osaka (1980), OA Port Tokyo (1984).

Concept work for the entire building of Toyota Motor Kyushu Plant (Lexus' main plant), mainly interior and exterior colour scheme for the plant (1993)

Hotel

Tokyu Corporation Hotel Group: Tokyu Hotel, Akasaka (1969), Seoul (1970), Ginza (1971), Hakuba (1971), Sapporo (1974); Tokyu Excel Hotel, Narita (1985), Sapporo (1996), Shibuya (2000); Tokyu Inn, Sapporo, Shibuya, Umeda, Kobe (excluding guest rooms), etc.; Tokyu Resort, Miyakojima (1984), Imaihama (1987), Saroma Lake (1985).

Keio Plaza Hotel, Keio Electric Railway Group, Shinjuku (1971), Hachioji (1994), Tama (1996).

Odakyu Electric Railway Group "Hakone Highland Hotel" (2002), "Yamano Hotel" (2010).

"Imperial Hotel" (1969).

"Kyoto Hotel" Chinese restaurant (1994).

Shops & Restaurants

The first Sony Plaza (now PLAZA) in Ginza (1966) and 40 other shops.

Kasumigaseki Building 36th floor, Tokyo Kaikan "Crystal Lounge" (1968).

Shiseido "The Ginza" main store (1974) and two other stores.

Bowling centre "Lapin Ball" (1972).

"Hana Juban" Azabu branch (1984).

Medical Affairs

Renovation of Hatsutomi Health Hospital (2013) and 6 other hospitals.

Renovation of Sun City Machida Retirement House (2015) and five other facilities.

Book

"Seven Designers for Shops" (co-author, Rikuyosha, 1986)

Co-author of "7 People's Commercial Space Design" Rikuyosha (1986)

"Susumu Kitahara's Modernism: 1960s-2000s / A Half Century of Interior Design" Parade (2018)

Interview

Interview

At a time when companies are losing interest in culture

The achievements of brilliant people should be passed on as a legacy

Special structure of interior design

— Mr. Kitahara, you have been at the forefront of Japanese interior design since the 1960s, and have been a driving force. In your book "Susumu Kitahara's Modernism 1960s-2000s: A Half-Century of Interior Design" (Parade), published in 2018. In the book, Shiro Kuramata, who is three years older than you, wrote "Kitahara's thoughts" in which he said "he was trying to understand interior design from a macroscopic and urban planning point of view rather than a microscopic one". The generation one year younger than you includes Shigeru Uchida and Takashi Sugimoto. Among them, Mr. Kitahara seems to have taken your own unique path, working on hotels and offices.

Kitahara In Japan, thanks to the success of Kuramata, Uchida, Sugimoto, and others, the work of atelier-style interior designers like them tends to be seen as the mainstay of the industry, but most of their work is focused on restaurants, boutiques, and other places where people play, so to speak, and their targets are limited. With these stars, the world of interior design has expanded. However, interior design is not only play environment oriented. We believe that it is important to create a comfortable environment based on a good balance of the three elements of human working, living and playing. And in fact, the majority of spatial projects, such as offices, hotels, and public spaces, are large in scale and complex, and many of them were never commisioned to atelier-style designers in the first place.

In my case, I belonged to an office with many Americans from early on, and I was entrusted with such a large project in that world when I was just 30 years old or less. That's why I'm the only one with a sub-culture, but in terms of the original flow of interior design work, this may be the mainstream.

When the economy boomed due to the bubble economy, people who worked like artists had jobs that suited their characters, and they drifted further away from the conservative work of the core industries. I am the only one left in this situation. Structurally, interior design in Japan is unique.

These projects were designed in the anonymised style of an organising office.

— It is true that there has been little coverage in the media of the interior design of key industries that originated in the pos-twar reconstruction period.

Kitahara After the war, as Japan rebuilt and its economy grew, American companies began to arrive in Japan, setting up offices and expanding their operations in the country. NCR brought American-style supermarkets to Japan and developed cash registers, while IBM introduced office automation and large computers to the country. The lifestyle of American civilisation and culture has been increasingly introduced into Japan, bringing with it American lifestyles and forms.

The Marunouchi office district was filled with foreign companies one after another. These large companies had accounting and law firms attached to them, and this became a civilised community. Naturally, these families would need flats to live in. I was once commissioned by the president of AIU to design a ski lodge in Yuzawa, but at that time there was no one in Japan who could build the kind of modern, sophisticated flats and hotels that they were looking for. Partly because our leader was an American, but also because we had developed a design style that could only be achieved by someone who had been inspired by Western design and culture, we were constantly receiving requests from foreign companies. The fact that we had sales staff who were fluent in the language was also an advantage in terms of communication.

— After graduating from Tokyo National University of Fine Arts, you worked at Tokyu Nihonbashi Design Office, and then moved to Pacific House, an interior design company where Americans work.

Kitahara The Tokyu Nihombashi Store was a department store, so it was focused on interior design products. We had to think about the space from the perspective of how to sell chairs and carpets. We end up becoming a coordinator rather than a designer. I joined Pacific House because I wanted to work on the spatial composition for the total living space.

— Pacific House was established in 1956 as the first design centre in Japan to offer total interior design and goods.

Kitahara The reason why Pacific House established an interior design company was because of the government's intentions. After the war, the U.S. provided a huge amount of financial assistance to rebuild a devastated and impoverished Japan, amounting to 12 trillion yen in today's value. Of course, it was a give-and-take with the expectation of benefiting from Japan's development later, but at any rate, there were no five— star hotels in Japan to receive the dignitaries on their mission to Japan. The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (now the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) had a strong sense of urgency. It was then decided that five— star hotels and other such interiors should be built as soon as possible, and that an organisation should be created to meet these needs.

It was an organisation of about 15 people, consisting of several young Americans and Japanese, and headed by an American architect named Dale Keller from the University of Washington, who at one time was a member of the Tange Institute at the University of Tokyo. We were responsible for the design of places for Americans to live and work. IBM had already developed an office design that included a modern, new American style of management, but there was no one in Japan who could apply it, so Pacific House was in charge of the design. We also designed most of the offices for foreign companies such as Mobil, NCR, and Citibank, as well as hotels such as Marunouchi, Okura, Palace, and Hilton. It was almost like studying in the U.S., where English was spoken in the office even though I was in Japan. As MITI had hoped, we were able to create a series of offices and condominiums for visiting dignitaries in response to American demand in Japan.

— So you joined the company and learned the cutting edge of American modernity.

Kitahara I was a young man when I joined the company, so I found the American modernist interiors to be bright, refreshing, and heartwarming. I learned a lot from Mr. Keller, not only about design, but also about the little comments and presentations that persuade others, all of which were completly unknown to Japanese people. However, management was also the American way, so it was not uncommon to come to work and find that the colleague sitting next to me had been fired the same day. I quit there after two years and started an organisation called Form International (Form) with five people, led by Hiroshi Yabuki of Pacific House, who was a project manager who understood architecture and English. I stayed there for three years, and when my work for Tokyo Kaikan and the Imperial Hotel was finished, I became independent.

Design requires sleight of hand

— You often work in collaboration with architects and designers such as Yoshinobu Ashihara, Shoji Hayashi, and Isamu Kenmochi.

Kitahara In 1968, FORUM received a joint project to create Tokyo Kaikan's "Crystal Lounge" on the 36th floor of the Kasumigaseki Building, and I participated as chief in charge. It was a request from Professor Yoshinobu Ashihara. Professor Ashihara was a professor at the University of Tokyo at the time, and he gave a lecture on architecture at the Marunouchi Rotary Club, which happened to be attended by Tokyo Kaikan Chairman Masatomo Yoshihara. Mr. Ashihara was personally consulted by Mr. Yoshihara about moving into the Kasumigaseki Building, and he readily agreed to oversee the design, but he felt a great sense of responsibility.

Kenmochi & Associates was in charge of the main dining room and we were in charge of the casual tea lounge, but the design team had to deal with the interior design restrictions of the first skyscraper. When the building was completed, Chairman Yoshihara was overjoyed and Dr. Ashihara seemed relieved of his burden. All the staff were really tired.

In this way, skyscrapers were extended towards the sky as a revolutionary movement, and at the same time, new cities were born underground, like underground shopping malls, and our living space was extended upward and downward, becoming the era of rapid economic growth that started the future-oriented dynamic city.

After this project was completed, Mr. Kenmochi asked me to participate in the interior design of the Keio Plaza Hotel, which I gratefully accepted, and just as the construction of the Imperial Hotel's Coffee House was completed, I left Form and started my own office. At the Keio Plaza Hotel, I was in charge of the "Young Bar" and the Chinese "Nan Yuan".

— Mr. Kenmochi died before he was 60 years old. If he had been active longer, the genealogy of design history might have changed after that. Did you work with Shoji Hayashi of Nikken Sekkei on the IBM Japan headquarters building in 1971?

Kitahara I was in charge of the lobby furniture, the audio room and the company cafeteria at the IBM headquarters. We needed about 1,000 seats in the cafeteria, but after the basic design was completed, the manager in charge of construction came to Japan from New York and strongly suggested that we could reduce congestion in the elevator hall by making the cafeteria on two levels. Since the basic design, which had already been approved by IBM Japan, had been completed, I rebelled against this suggestion and stepped down as the person in charge of the cafeteria area.

Mr. Hayashi of Nikken advised me, "You are young. You should be more careful in your long life". According to him, the entire process and construction cost of this project had already been decided between the head office and the top management in Japan, so there would be absolutely no change. Mr. Hayashi was right, so we went back to the current plan, and another designer was assigned to the project, and I lost tens of millions of dollars in design fees and about a year of design time. Since then, I have always remembered that an emotional temper is a bad temper.

As for Mr. Hayashi, the Palace Side Building, one of his masterpieces, took the world by storm by visualising the gutter through which rainwater passes as a design rather than concealing it within the curtain wall. He was truly a man of genius. It is not often that the number one person in the conservative Nikken Sekkei organisation is a design conscious person. Since that time, I've had many relationships with IBM, and Mr. Hayashi often advised me, "Mr. Kitahara, you have to have magic tricks in design".

— Magic tricks, huh?

Kitahara I interpret magic as the esprit and wit in the design. When I was working on the showroom for Fujie Textile in 1972, Mr. Hayashi came to see the showroom and said, "You have a little magic trick, just a little". A magic trick requires you to create the seed yourself. In this showroom, I applied the balancer of a pulley, which is suspended from above to carry goods in factories, and used it to display movable textiles that can be pulled freely. It also creates a change of vertical movement in the space. Mr. Hayashi said, "It (the balancer itself) wasn't your idea, but there's a bit of magic in the way you use it" (laughs).

However, there was absolutely no response from the interior design world. Only two magazines, "Geijutu Seikatsu" and "Geijutu Shincho", recognised that design is anonymity, but the interior design journalism didn't appreciate it. It may have looked like an anonymous design that just used the power of the balancer.

On the contrary, the bowling alley in Ginza 7-chome, Lapinball, was a huge hit. The architectural design was done by Takenaka Corporation, but the president came to the completion ceremony and told his subordinates, "It's interesting, you guys should go see it," so Takenaka employees lined up to see it. It was regarded as a revolutionary design in the interior design world. The gutter line on the floor was suspended from the same ceiling surface, and the rest of the ceiling was mirrored to create an optical illusion effect.

Fujie Textile showroom (1972)

Photo by Yoshio Shiratori

— So the reactions were contrasting. But you could say that "Fujie Textile" became, in a sense, a prototype for one of the textile exhibitions. In a later interview with Mr. Sugimoto in "Shoten Kenchiku", Shigeru Uchida mentioned this showroom as an interior design that shocked him. Also, at the Shiki Fabric showroom in 1974, Kuramata used a magnet to attach fabric to the floor and make it float, probably with an awareness of your work. I think Mr. Kuramata must have been disappointed to see this.

Kitahara I don't know. Kuramata and his colleagues were creating their own world, which was different from the work I was doing as a design business within a large organisation. They nurtured not only those who would follow in their footsteps, such as Uchida and others, but also small but dreamy clients, but after two or three years, their design lives would wear out and become increasingly short-lived. Mr. Kuramata would only do work that allowed him to do what he loved, so he would voluntarily turn down big jobs, saying, "I don't want to do anything big". I don't think there has ever been anyone with that much talent. His work is still shining in the history of interior design. It's a pity it was so short-lived, but the legacy of great design remains strong even today.

Not alive in writerly terms.

— Takashi Sugimoto and Motomi Kawakami are your juniors at Tokyo University of the Arts, but at the time when you were enroled, were there not many people aiming for interior design?

Kitahara At the time, Japan was trying to export its industrial products to the world, such as Sony's transistor radio and Honda's Cub. However, the world ridiculed Japanese products for their lame design, even though they performed well. Even in the 60's, professors at the University of the Arts actively tried to get students to work in industrial production in response to strong demand from the industry. In this developing country, if you don't put up a flag and urge people to look this way, the power will be dispersed and you won't become powerful. That's why everyone went in that direction, but I was different. I thought that from now on, design would be oriented towards space. We didn't even have the word "interior design" yet, and we called it tacky interior decoration.

Hatanaka What was it that made you focus on space when the trend was towards products?

Kitahara I don't remember exactly, but in industrial design, for example, televisions, washing machines and refrigerators are just square boxes with packaging. I guess I didn't find that attractive. One of my classmates was a designer named Atsushi Ishiyama. He was very talented. He was the president of GK Dynamics and designed Yamaha motorcycles. I thought that motorcycles were interesting. Even when the engine is not running, they must have a form that looks as if they are going to run, and there is a dream of speed in them.

Ishiyama was asked by a professor if he wanted to stay at the school and pursue a career as a teacher, but he refused, saying he had no interest in it.

When Japan was at its poorest, it developed by making up for what it lacked, and the United States, which supported it, benefited from Japan's economic growth. Since then, Japan has become completly dependent on the United States, but now, like the United States in the past, Japan is sending a new wave of culture and civilisation to Asian countries. It is through interdependence that the economy develops. In order to enrich their lives, people want not only rugged machines, but also tools and objects with warm dreams. There is a need for a variety of designs. Humanistic and warm design will be closely linked to the economy, and will develop more and more while being interdependent.

— In your thirties, you were entrusted with a major job, and you have continued to work in key industries without interruption.

Kitahara I think we were lucky that way. When the economy went into recession, Uchida and Sugimoto once said to me, "When we were going through a tough time, Mr. Kitahara was lucky". But their talents opened up because they stood up to us and said, "What the hell". We don't need big names like artists for our work, and I haven't lived my life like a artist either.

Also, at present, big jobs, whether for hotels or shopping centres, are being absorbed by large organisations, with the likes of Nomura Kogeisha and Tanseisha taking on all the work. Unfortunately, there doesn't seem to be a design environment where a lone wolf big name can leave something behind as an atelier. It's becoming more and more conservative, and large companies tend to prioritise relationships with other large organisations. It would be nice if there were sponsors who would let young, fast-growing people do what they want on a guerrilla basis, like there was a long time ago, but it seems like they're more concerned with protecting the company than being creative, and they're not interested in culture, and they're not spending money on it. And the IT chiefs are only interested in Michelin. In this sense, we can say that Japanese architectural design culture is in danger of dying out.

That's why, more and more, we have to leave a legacy of the achievements of the people who have come before us, and I think it's increasingly important to do so. It's important to be able to properly convey the necessary information about their achievements in an archive. It takes a lot of energy to do that, though.

A book is an archive

— Now, let me ask you about the status of your archives, Mr. Kitahara. You recently moved to a new office, but what is the state of your drawings, sketches and other materials?

Kitahara I brought the CAD data to the new address, but I donated all the tracing paper drawings that had not been converted to CAD to the Kanazawa Institute of Technology Architectural Archives. When we moved, we had to discard all of them, but Kazumasa Yamashita, the architect, said that would be a waste of money, so we donated them to the Kanazawa Institute of Technology.

When I asked Kanazawa Institute of Technology for his advice, they said they would take on as many projects as I wanted, and I sent them a set of Trepe drawings covering hundreds of projects for 30 to 40 years.

— We have had the pleasure of interviewing him twice so far. Since he is in charge alone, it seems to take a lot of time to organise the files, but he has kept them in order.

Kitahara For example, it might have been helpful if I had sorted them by item, such as hotel, office, or Sony Plaza, but I couldn't even do that on a daily basis, so I just handed them over. I don't see much cultural value in my past work, and I don't have any desire to preserve it for posterity. So I didn't want to keep them at all. I am no longer active in design, and my social mission as a designer is over. I was so busy with the moving process that I threw away all the bricks, tiles, carpets, etc. that I had stored in the warehouse, as well as all the samples. The cost of that process was quite high. But there were some things that were a bit disappointing to discard, like the colour schemes we used for the project process.

Hatanaka I worked at K.I.D. Associates for 13 years until 1992 as chief of staff. At that time, there were about 10 staff members, and we were always busy with about 10 projects. The projects were running concurrently, and there were many of them. Each file had a project name, but we didn't have time to organise them by field or anything like that.

— Kitahara-san, your work is covered in this collection, isn't it?

Kitahara This was directed by Takahisa Kamijo, a graphic designer who was also a junior at the University of the Arts. This one book contains all the major works of interior design, which has been my life's work for nearly 50 years. All the photographs were taken by Mr. Yoshio Shiratori. I also tried to include as much text as possible in the book, rather than just photographs and drawings. You can read and understand how the interior design developed and how it was born from the interaction with the client. Mr. Kuramata and other third parties also wrote articles for the magazine. I also re-recorded some of the articles that had appeared in "Japan Interior" magazine, which was at the height of its popularity at the time.

— In 1986, you also published "The Modernism of Susumu Kitahara".

Kitahara We also made an English version of the book, which sold 4,000 copies on the East Coast, mainly in New York. In Japan, it sold about 1,000 copies. It was a time when Japan was in the midst of a bubble economy, so the Americans must have been interested in Japan and Tokyo.

— It shows the booming interior design of the mid-80s.

Kitahara Let's talk about liberal street design. Each of the spaces we designed fulfiled its mission and was then torn down, and since then it has lived on in photographs showing its current state. Among the restaurants I have designed, there is one that has been operating economically for over 30 years without any changes to its interior. It's the yakiniku restaurant Hana Juban in Azabu Juban, and it opened in 1985, so it's been 35 years now. The average lifespan of a fashionable restaurant in the central Tokyo area is about 10 years, at which time they change their business model, but this restaurant has remained unchanged to this day. It's the only one with longevity in my more than 50 years of design life, and it's an unusually casual type of business for me. I thought it would be nice if you could cheque out my designs while eating yakiniku, so I introduced them to you. I think this kind of thing is an archive of survival preservation.

I remember Takashi Sugimoto's "Bar Radio," which was renovated 10 years after it opened and lasted for more than 20 years, was a good bar. Coffee houses in city hotels are heavy duty and are considered all day dining, morning, noon and night, and 10 years is their lifespan and they are always refurbished. Literally, 10 years is a lifetime for interior design software and hardware.

— Earlier, you talked about the importance of the archives of Kuramata and other atelier artists. As one of the leaders of Japanese interior design, do you have any desire to pass on this culture to the next generation?

Kitahara In the past, Mr. Kuramata was surrounded by a cheering section of youthful apparel and other industrialists who were riding the tailwind of the high economic growth period. They said, "Kuramata, do what you want to do, but let us do the rest!" And so on. I rode the coattails of the times and was blessed with more than my fair share of big projects in the 60s and 70s. Veterans of the industry gave up their seats and encouraged us, saying, "It's your time now". It was a good time. As for the future, of course, there is a lot of excellent cultural information from the past, especially from the 60s and 70s, when design was in its infancy, and we need to preserve it carefully. What worries me is today. Contemporary creative culture is completly lacking in vitality, and if there is any information to be found, it is in the form of specialised paper-based media such as "Japan Interior", "Architectural Culture" and "SD", which have all ceased publication, and the remaining magazines have lost their former vigor. Even if we have created cultural information, we have lost the media to distribute it.

The Internet is a medium that excels in speedily conveying cause and effect, but it tends to produce flimsy information, and in the current state of devastated culture since the 2000s, we are in the slow and insensitive process of the boiling frog phenomenon, so to speak, and I am worried about the future in which sensitivity and intelligence will degenerate as a result. I am worried about the future when our sensitivity and intelligence will degenerate.

— I think that is also a frank opinion. I was able to hear a lot of frank talk. I think we were able to hear a lot of valuable history of interior design. Thank you very much.

Hana Juban" Azabu shop (1984)

Photo by Yoshio Shiratori

Contact information for the location of Susumu Kitahara's archive

Architectural Archives Research Institute, Kanazawa Institute of Technology

http://wwwr.kanazawa-it.ac.jp/archi/

Maru Kitahara / Informal Co.