Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Kazuko Koike

Creative Director

Date: 4 August 2021,16:30 - 17:40

Location: Remote interview

Interviewee: Kazuko Koike

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

Profile

Profile

Kazuko Koike

Creative Director

1936 Born in Tokyo.

1959 Graduated from Waseda University with a degree in English Literature. Joined the Ad Center, where she was responsible for editing and writing.

1961 Resigned from the company and became a freelancer. Founded Comart House with Isamu Takano and Tamotsu Ejima.

1962 "PRINTING INK" magazine is published, with Ikko Tanaka as AD. Interviewed Issey Miyake.

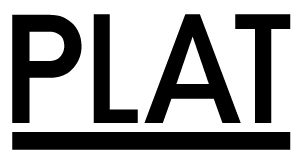

1969 Participated in the launch of Ikebukuro Parco and has since been involved in advertising and public relations activities and event planning for the Seibu Group.

1975 Organised the exhibition "Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939" at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, and was responsible for the planning, implementation and production of the catalogue. Retirement from Comart House. Invited by the University of Hawaii to train in curation (September 1975 - March 1976).

1976 Establishment of Kitchen Inc. In response to Ikko Tanaka's call, she was one of the founders of Tokyo Designers Space.

1979 Appointed Associate Curator at Seibu Art Museum. Participated in the planning and supervision of MUJI (launched in 1980).

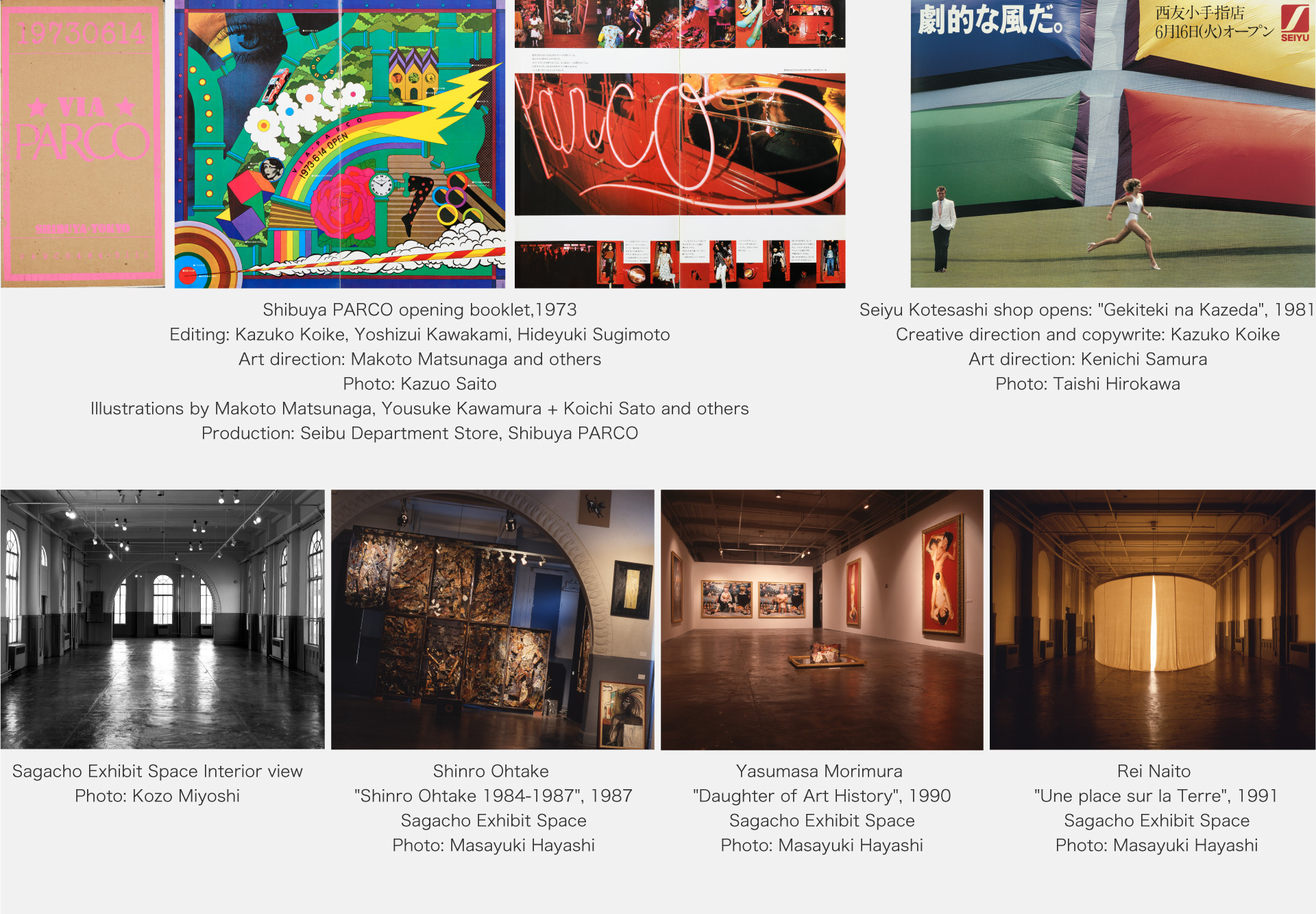

1983〜2000 Founder and director of Sagacho Exhibit Space.

1986 Wrote a book entitled "5 Sensors of an Age (Hi-pop design series)" (Rikuyosha). She was awarded the Mainichi Design Award for "the activities of five designers and Kazuko Koike".

1987〜2006 Professor at Musashino Art University, Department of Spatial Design.

1989 Curated and edited the catalogue for the exhibition "Frida Kahlo: Love and Life, Sexuality and Death in the Bodyscape" at the Seibu Art Museum.

1995 Awarded the Japan Contemporary Arts Promotion Prize.

1998 Curated and edited the catalogue for the exhibition "50 Years of Japanese Lifestyles" at the Utsunomiya Museum of Art, which travelled to the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art in 1999.

2000 Curated "City of Girls" for the Japanese Pavilion at the 7th International Architecture Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia.

2008 Went to London to study contemporary art again.

2011 Establishment of "Sagacho Archive" in 3331 Arts Chiyoda.

2012 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT "Ikko Tanaka and Future/Past/East/West of Design" exhibition curator.

2016〜2020 Director of the Towada Museum of Contemporary Art.

2017 Won the Avon Women of the Year Award.

2019 Awarded of Merit, 22nd Japan Media Arts Festival.

2020 Curated "Sagacho Exhibit Space 1983-2000: Fixed Point Observation of Contemporary Art" at the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma. Awarded by the Commissioner for Cultural Affairs.

2021 General Director of the Tokyo Biennale 2020/2021.

2022 Exhibition "Alternative! Kazuko Koike Exhibition - Soft-Power Movement of Art & Design" at 3331 Arts Chiyoda.

Description

Description

An archive that can be passed on to the next generation is not only the material of the work, but also the process by which the work or project was completed, and the traces of this process can be the seeds of the next creation. Kazuko Koike has been at the forefront of design and art for a long time, quickly discovering talented people, creating spaces and bringing new ideas to the times. She is also a creative director. She was involved in the launch of MUJI and continues to serve on its Advisory Board. She has also worked as a copywriter, translator, author, producer, curator and educator. The essence of Koike's work is to connect people with each other and to bring to the world a creativity that can only come from the present, and which is difficult to grasp in isolation. This is why Koike herself has become what could be called a living archive. In recent years, she has published a series of books looking back on her life, and has also been working on the archiving of Sagacho Exhibit Space, which she presided over, in order to bring out the tangible and intangible traces of creativity that she has woven with creators.

She was the fourth of five sisters born to Tokumitsu Yagawa, an educationist, and was adopted by her mother's sister Motoko and Mr. and Mrs. Koike Shiro. Shiro Koike, who were social activists who founded a publishing company called Clara-sha, and her childhood spent shuttling between the two families became the starting point of her unconventional way of life.

After studying under the graphic designer Seiichi Horiuchi, she began her career as a copywriter at Ad Center. In the 1960s, she became independent, and was quick to detect and collaborate with the talents of Ikko Tanaka, Issey Miyake and Eiko Ishioka.

In 1975, Koike was the producer of the legendary "Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939" exhibition at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, which was born out of a visit to the "Inventive Clothing" exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York with Makiko Minagawa, who had been invited by Miyake to see the exhibition. The exhibition made a big splash as it was the first time that fashion as a culture was introduced in Japan. Koike's interest in exhibition planning led her to study curation at the East West Center, a research institute at the University of Hawaii, before 1983 founding and running Sagacho Exhibit Space, Japan's first non-profit alternative space to museums and galleries. She has a natural talent for discovering new talent that has yet to be recognised, and from here has emerged artists such as Yasumasa Morimura, Shinro Ohtake, Rei Naito, Hiroshi Sugimoto and many others who have gone on to work internationally. The gallery closed in 2000 due to the age of the building, but in 2011 she established the "Sagacho Archive" within 3331 Arts Chiyoda, and is curating the "Sagacho Exhibit Space 1983-2000" exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma in 2020. In 2016, she was appointed director of the Towada Museum of Contemporary Art (-2020), and was appointed general director of the Tokyo Biennale 2020/2021. She is also working on the idea of a free school for children to develop their creativity. The aforementioned "archival activities" seen in recent years could be a valuable resource for this purpose.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Books

"Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939", edited by Kazuko Koike, Kyoto Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 1975; "Issey Miyake East Meets West", edited by Kazuko Koike, composition by Ikko Tanaka, Heibonsha, 1978; "Mackintosh's Design Exhibition: Furniture, Architecture and Decoration", edited by Kazuko Koike and Yoshio Takebe, Seibu Museum of Art,1979; "Japanese Coloring", composition by Ikko Tanaka and Kazuko Koike, Libroport, 1982; "The Undercover Story", edited by Kazuko Koike and Mitsuko Watanabe, Atsuko Koyanagi, Body Fashion Association and Kyoto Costume Culture Research Foundation, 1983; "Péro Isaka Yoshitaro's Works", edited by Ikko Tanaka and Kazuko Koike, PARCO Publishing, 1983; "Snoopy in Fashion", edited by Kazuko Koike, Libroport,1984; "5 Sensors of an Age (Hi-pop design series)", edited and written by Kazuko Koike, Tadao Ando et al, Rikuyosha,1985; "Fashion Word Collection", by Kazuko Koike and Akiko Fukai, Kodansha,1985; "Mujirushi no Hon (The Book of MUJI) ", planned and edited by Kazuko Koike, designed by Ikko Tanaka, Libroport,1988; "Aura of Space", by Kazuko Koike, Hakusuisha,1992; "50 Years of Japanese Lifestyles", curated by Kazuko Koike, Utsunomiya Museum of Art,1998; "Fashion: Fashion as a Form of Polyhedron", written and edited by Kazuko Koike, Musashino Art University Press, 2002; "On Conceptual Clothing", planned, supervised and edited by Kazuko Koike, Musashino Art University Art Resource Library, 2005; "Ikko Tanaka and Future/Past/East/West of Design", planned and edited by Kazuko Koike, FOIL, 2012; "Where Did Issey Come From?", by Kazuko Koike, planned by Midori Kitamura, Heil, 2017; "MUJI IS", edited by Kazuko Koike, Ryohin Keikaku, 2020; "Bijutu / Chukanshi: Koike Kazuko no Genba (Art/Meson: The work of Kazuko Koike)", by Kazuko Koike, Heibonsha, 2020; "Nokosu kotoba Koike Kazuko: Hajimari no Tane wo Mitsukeru (Finding the seeds of beginnings)", by Kazuko Koike, Heibonsha, 2021

Translation

"The Woman with the Flowers: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago, Feminist Artiste of the West Coast", by Judy Chicago, Parco Press, 1980; "Alulu: A Beautiful Life", by Diana Vreeland, Parco Press, 1981; Translation of the musical "Cabaret", 1982, Hakuhinkan Theatre, etc.; "Eileen Gray: Architect Designer", by Peter Adam, Libroport, 1991, new edition Misuzu Shobo, 2017

Advertisement

"PARCO Kankaku", art direction and design by Eiko Ishioka, illustration by Harumi Yamaguchi, copywriting by Kazuko Koike, photography by Kazumi Kurigami, 1972; "Wakeatte Yasui", art direction by Ikko Tanaka, illustration by Yuzo Yamashita, copywriting by Kazuko Koike, MUJI, 1980; "Shizen, Tozen, Mujirushi", art direction by Ikko Tanaka, illustration by Makoto Wada, copywriting by Kazuko Koike, MUJI,1983

Exhibitions and projects

"Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939", planning, execution and catalogue editing by Kazuko Koike, art direction by Ikko Tanaka, space design by Takashi Sugimoto, mannequins by Ryokichi Mukai, The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto,1975; "Issey Miyake. A piece of cloth", curated by Kazuko Koike, Seibu Museum of Art, 1977; "Mackintosh's Design: Furniture, Architecture and Decoration", curated by Kazuko Koike, Seibu Museum of Art, 1979; Osaka International Design Festival "Modern Design", 1983; "Magritte and Advertising", curated by Kazuko Koike, Sagacho Exhibit Space, 1983; "The Undercover Story", curated by Kazuko Koike, Laforet Museum Harajuku, 1983; "Japanese Design Tradition and Modernity", organised and implemented by Kazuko Koike, Central Artists' Hall of the Union of Artists of the Soviet Union,1984; Higashikawa cho, Hokkaido, Japan, participated in the establishment of the Higashikawa Prize, a photography award, 1985; "Three Women: Madeleine Vionnet, Claire McCardell, and Rei Kawakubo", New York Fashion Institute of Technology, 1987; "Earth & Sky: Naga Folk Art", curated and supervised by Kazuko Koike, Yurakucho Art Forum, 1988; "Frida Kahlo: Body Landscape of Love, Life, Sex and Death", curated and edited by Kazuko Koike, Seibu Art Museum, 1989; "Yves Saint Laurent: Innovation and Glory of Fashion", curated by Kazuko Koike, Saison Museum of Art, 1990; "Ikko Tanaka and Future/Past/East/West of Design", curated by Kazuko Koike, 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, 2012; "Sagacho Exhibit Space 1983-2000: Fixed Point Observation of Contemporary Art", planned and curated by Kazuko Koike, The Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, 2020; "Tokyo Biennale 2020/2021", general directed by Kazuko Koike

Interview

Interview

Budgets for archives should be

created by the state as a cultural policy

Oral history is important

ー In 2020, you published a book entitled "Bijutsu/Chukanshi: Koike Kazuko no Genba" (Heibonsha, written by Sonoka Yasuda), and in 2021 a book entitled "Nokusu Kotoba: Koike Kazuko Hajimari no Tane wo Mitsukeru" (Heibonsha). The word "chukanshi (meson)" in the title of the former is a word that came to you when you thought about your own position in your long career as a creative director working with Ikko Tanaka and Issey Miyake, and is taken from the role of holding matter together in physics. I believe that the archive of your activities as a meson includes your books, including your writings. Today, we would like to ask you about your archive. We would also like to hear your opinion on how you see the design archive.

Koike As the General Director of the Tokyo Biennale 2020/2021, I have been one of the busiest in my 85 years of life. In the midst of my busy preparations, I published a book entitled "Nokosu Kotoba: Koike Kazuko Hajimari no Tane wo Mitsukeru". I think that leaving an archive is a very difficult thing to do. Basically, in my case, I think that oral histories and videos are the archives.

As a creative director, I have always valued bringing together professionals in the creative field and using me as a medium to connect people with each other. If it's a graphical visual work, it's ultimately the designer's work that goes out into the world. In the case of my work, I collaborate with designers and other professionals, so it's not just my work, and it's not just about me. It's different from a designer's archive where the visual expression comes first, so in my case I think it's better to use it as a reference case.

Even if the final result is a visual expression, I am someone who started my relationship with design in the realm of words, so it is important for me to know how the words came to be, which is difficult to preserve in a tangible form. I am keenly aware of the importance of preserving an oral history of how these words came to be, while they are still in our memories.

ー You were involved in the launch of MUJI with Ikko Tanaka and have been active in the company for a long time. You have also done copywriting for Parco with Eiko Ishioka. You have curated several high-profile exhibitions, including, "Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939" at the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, and "Frida Kahlo" at the Seibu Museum of Art. You have also curated events on a global scale, such as the Japanese pavilion " City of Girls " at the 7th International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale.

You have also curated Sagacho Exhibit Space, the first alternative space in Japan, and your work is very diverse and wide-ranging. In addition, you are also involved in translation and education, and have written many books. Your are Creative Director. I assume that your job involves writing proposals first. Do you have a direct archive of proposals, mapping and graphic materials for planning? Are those recorded for each project or do you keep a record of them?

Koike That's not good at all. We've been running and making things, and we haven't put much effort into storing and organising them by project, so now we're in a panic. I wanted to compile a list of all the work I've done, so I've been doing this kind of looking back since about 2019.

In 2020, I organised "Sagacho Exhibit Space 1983-2000: Fixed Point Observation of Contemporary Art" at the Museum of Modern Art, Gunma, and edited and wrote the catalogue for the exhibition. In addition to the two books mentioned above, I edited and wrote "MUJI IS" (Ryohin Keikaku) and The Asahi Shimbun also ran a column called "The Gift of Life".

In the process of looking back, I've collected various ephemera, such as proposals and flyers, and I've noticed that some of them are missing, little by little, and I'm reflecting on them. Many things have been lost in the process of moving from one office to another.

Many designers have their work neatly organised as an archive in their office. By comparison, we tend to be messy and disorganised. When we ask designers we have worked with if they have any of our work, they often have it in their archives, so we have to rely on them for help.

Passing on an identity for the next 30 years

ー Do the parent companies of the Saison Group, Parco advertisements and Seibu Museum of Art exhibitions from the 1960s to the 1980s still have their own materials?

Koike We are also acutely aware of the difficulties that companies face when it comes to archiving. The harsh reality is that even MUJI, which was born in 1980, does not have the products and advertising productions that it should have. In fact, we have been very insistent on the necessity of archiving, but in reality it is very difficult to set up a budget for it and to secure human resources.

In 2020 we published the book "MUJI IS " (Ryohin Keikaku), but we had to make an effort to find things that we could look for in our memories and channels, and we have already started to do that.

The background to the creation of a particular poster does not come out in the open. When I was writing copy for MUJI in the 1980s, and I was wondering how to express myself, I was talking to Makoto Wada, who was in charge of the illustrations, and we said, "Of course it's natural, but the nature that surrounds us doesn't have any kind of branding". I asked him if it was possible to express the strangeness of the fact that people today are not aware of this natural thing. Then Wada-san drew an illustration of a child with a Jupiter-shaped hat on his head and Jupiter floating outside the telescope. So the similarity was kind of strange. It's obvious, but it creates something strange. It was the copy "Shizen, Tozen, Mujirushi." that put it into words. This was the copy.

Then, in 2015, Kenya Hara became the director of MUJI, and when he made a corporate advertisement about the similarities between the creatures of the Galapagos Islands and MUJI products, he thought it was appropriate to use this copy again. It's one of those things that happens when a company and a designer come together to use it again in a different way over time.

I thought it was important to convey the drama behind the creation of a visual work as a record of the times as an archive. It's an interesting example of how the identity and spirit of a company can be transmitted over 30 years.

ー It's not easy for a designer to put into words what is difficult for a visual designer to do, but you have been able to put into words what is difficult for a visual designer to do.

Koike It depends on the context in which each piece is created. Mr. Takashi Sugimoto, who designed the MUJI shops, and I worked closely together, and we never had any detailed discussions. The first shop in Aoyama debuted in the category of lifestyle. The design of the shop and the way it was furnished was a result of Mr. Sugimoto's understanding of the MUJI identity that Mr. Tanaka and I had created, and he quickly gave it shape. For example, he used bricks from a blast furnace for the walls and old tubs for the fixtures. There was a sense of nostalgia, and Mr Sugimoto was a designer who was able to show through his materials that this was MUJI. With people like that, it's like an A-Un breathing.

ー MUJI's value was in the very materials he used. The difference in materials shows that it is not Shiro Kuramata, but Mr. Sugimoto.

Koike Mr. Sugimoto's certainty about materials has been the most important thing for MUJI, and his suggestions about earth, metal, wood... appear without discussion. This is because we share the same sense of corporate identity, and Mr. Sugimoto understood what Ikko Tanaka was aiming for, and expressed it more dramatically.

Empathy needs time to develop

ー However, because it can be formed in such a way, the answer is in the head, and the process of getting to that point is not easily expressed in form, so it does not appear in the archives. I think that in order to understand each other, you need to be able to empathise. You often travel with creators, but have you made any effort to cultivate empathy, for example by spending time looking at beautiful things?

Koike Yes, there was a time when we had to make a run for it. I think it was a time when we had more time to relax. The first time I worked with Mr. Sugimoto was for the exhibition "Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939", where I asked him to create an installation for the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, as a young designer who appeared like a comet with bar "Radio". We invited Ikko Tanaka to be the AD. I've known Mr. Tanaka since I asked him to be the art director of "PRINTING INK" magazine published by Comart House in 1961, when he was still working at Nippon Design Center, but that time when young creators met each other was just the beginning. We both really like to eat. We had a lot of sympathy for each other's feelings about food, clothing and housing. That's why when we stand in the actual place of work, there is an A-Un breathing, and maybe it's a way of working that doesn't involve creating a project on the spot for the first time. We're both people who are constantly creating, and I think that was the basis of our sympathy.

The fever of the times that made One Week, One Show possible

ー Mr. Tanaka and you were the founders of Tokyo Designers Space (TDS), which was established in 1976 and later had its own space in the Axis Building. You became the founders at the request of Mr. Tanaka. Until it was disbanded in 1995, 250 creators from different genres got together and held weekly exhibitions as "One Week, One Show". I think that such a place was also a mechanism to create a springboard, and in those days there was time to make it possible.

Koike It is the TDS archives that I am interested in what is going on. I would like you to look into it. You have done something very valuable. The main theme was to create a circle of people, led by Mr. Tanaka, and to create a place where people from different genres could get together. In the field of design, we have industrial, interior, graphic, fashion, architecture, and we also have a copywriter, Shinzo Higurashi. It may be said to be one of the new youth movements stored up by the late seventies. The members paid a monthly membership fee, from which the rent of the space was paid, but it was a space that was created by everyone, a true artist initiative, which I think is rare in the history of Japanese creativity.

Every week there would be a solo exhibition by one of our members and it was a real competition for expression. There was always a party on the first day, including food and drink, and the theme was what to drink and what to eat. It was very difficult because we were all very particular. It was a miracle of the times that we were able to keep doing it, and it would have been unthinkable in the days of Corona.

ー It was a time when the economy was booming and the demand for design was doubling, growing and permeating the world. I'm sure you were all very busy, but I can't help wondering how you managed to find the energy to do all those things. Did they have time to spare?

Koike We couldn't afford it, but we were making it up as we went along. I think it was a time when we were caught up in a kind of fever. The Japanese economy was on the upswing, and soon we started to hear from members that they couldn't afford to pay their membership fees, and we thought that the times and the environment were changing, so we pulled back. I think the economic environment is a big factor.

ー Mr.Tanaka was at the top of the graphic world, but did he also have a strong will to promote not only the graphic world, but the design world as a whole?

Koike Mr. Tanaka is a lover of both theatre and music, and when he was young he aspired to the world of the Ballets Russes and opera, and I think his goal was to create a culture for the times that would unite and create through dramatic theatrical expression. I have been involved for a long time in the creation of places where people can come together and interact, and have been instrumental in the creation of not only TDS but also the Ginza Graphic Gallery (GGG) and TOTO's Gallery MA.

ー You studied theatre at Waseda University, where you gained experience in Jiyuu Gekijo. I read in one of your books that Mr. Tanaka worked on stage art posters and were close to Butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata, and that you became friends with him from the first time you met because you had theatre in common. It's well known that Arata Isozaki was a fixture in Shinjuku, where underground culture and anti-war folk music flourished, and Juro Kara's Aka Tent was located at Hanazono Shrine. There was also Shuji Terayama's Tenjo Sajiki, Tadashi Suzuki's Waseda Sho Gekijo and Makoto Sato's Kuro Tent, known as the "Four Heavenly Kings of Underground". I feel that they all shared this exciting time, when the spectacle of the city could be experienced through graphics.

Koike When I look back on those days, what I am proud of is that there was an attitude of creating our own culture, rather than retrospectively studying and re-enacting history. There was student theatre, because we were doing creative theatre, but I think it was because of this that we came to the standpoint of contemporary art. I think it is important to put aside the masterpieces of art history and focus on the creative work that comes out of me now. It was a time when the main focus was on what we wanted to express now. We put a lot of effort into creating an environment where that could be expressed. The willingness and passion to create new things made the small theatre interesting, and that was the momentum of the time. I think that was my starting point.

The first alternative space in Japan

ー Sagacho Exhibit Space is an alternative space in the Shokuryo Building in Koto-ku, Tokyo.1983 Alternative means outside the mainstream, was this inspired by the existence of places in design such as GGG, where you and your colleagues have been working?

Koike I was more influenced by what was going on abroad than by what was going on in the domestic design scene. It opened my eyes to what was happening in New York, London and Paris. In those cities, there were places where artists could co-create and work together in a way that was not possible in so-called commercial galleries. I realised that it was possible to do something like that in Japan, and that's what led me to Sagacho. It was set up by Atsuko Koyanagi, who now runs the Koyanagi Gallery, and Miyako Takeshita, an art researcher. As I wrote in my book "Aura of Space" (Hakusuisha,1992), man-made structures and organisations, such as government offices, eventually become skeletal and conservative. There were no opportunities for inexperienced emerging artists in Japan at that time. There were galleries for established artists, but they did little more than charge a rental fee to emerging artists. This situation is the reason for the creation of Sagacho.

ー So it is an alternative, "another place", neither a museum nor a commercial one. Until the closing of the gallery in December 2000, 106 projects were held and 400 creators were presented. As an emerging artist, you discovered young people who were not yet appreciated and gave them opportunities. What were your criteria for selecting them?

Koike The key word was to have the first show in Japan. As far as using the space we offer, we look for artists who will give us their first solid solo show. Yasumasa Morimura, Shinro Ohtake, Rei Naito, they all do. That has naturally become our policy.

ー TDS is membership fee based and Gallery MA is capitalised by TOTO, while Sagacho was funded by you and your company Kitchin. It was an operation that was only possible because of your boldness.

Koike That's why the business was always in the wind. When the economy was strong, we put the money from the project into it. We were stuck doing it that way, and there was a small part of us that felt that if we had been in the dealing business we might have survived, but we wanted to keep it as independent and self-sustaining as possible.

ー Why is that? I think it would have been possible to find a sponsor if you had offered. I bow to your integrity.

Koike I appreciate that you see it as a graceful move, but I think it was a bit reserved on my part. There is something to be lost by having a capital relationship. It's a difference in mindset that I've developed, so it's a result of that policy.

ー Since the exhibition "Origins of Contemporary Clothing: Inventive Clothes 1909-1939", you have shifted your work from advertising to exhibition planning and curation.

Koike After that exhibition, I was invited to study at the University of Hawaii, where I majored in curating. At the stage when I learned that there was such a thing as a curator and chose it, I switched from working in advertising to working for the Seibu Art Museum. After that, I founded Sagacho because I felt that it is not possible to have a sponsorship from the beginning if there is a form that we want to express independently.

At Sagacho, we do not have a dealing contract with the artists. We do sell the work that is shown, but where a typical gallery would have a 50:50 dealing contract with the artist, we try to make it 30:70, or at least 40:60, so that the artist gets as much benefit as possible.

ー You established the "Sagacho Archive" in 3331 Arts Chiyoda in 2011. What is it about?

Koike The basic archive. In the course of our activities at Sagacho Exhibit Space, we have received donations and purchases of artists' works. The aim is to share and inform people about these things as much as possible.

ー I see that you have the works and data etc. Do you plan to keep them as an archive in the future?

Koike We have a shelf called "Sagacho Project", where we put all the books. It is an archive to be given away in the future, but it is still in the process of being organised. There are a lot of interesting things in the exhibition records, but 3331 does not have the capacity to make use of it, so we are trying to put it somewhere else. I would like it to be passed on to future generations as a valuable resource for contemporary art.

The importance and challenges of design archives

ー I also visited "Sagacho Exhibit Space 1983-2000" at the Gunma Prefectural Museum of Modern Art, I mentioned earlier. Like the exhibition at that time, if we can feel the background of the time together, it becomes a more three-dimensional archive. In your case, you often work together with art directors, but sometimes you have to borrow works from the artists or ask for permission to exhibit them. Rights issues are one of the difficulties in archiving.

Koike That's exactly where we've hit a wall. In fact, now that digitalization is progressing, I think that the archive business can be a business, and it is progressing in national museums. On the other hand, if there is an organisation that manages an archive with the consent of the copyright holder, I will have to ask permission to use the work, even if I am a co-author. There are many people involved in a work. The rights of the creator and co-creator should be considered in the future development of the archive, and I would like to fight for it. I think there should be more discussion.

ー A work of art is the sole property of the artist, but a design involves many different people, organisations and companies, including the client. There are a lot of permissions and applications that need to be made for just one design, and this is one of the reasons why it is so difficult to establish a design archive. Although the need for a design archive has been raised for a long time, there is still no design museum or other design archive organisation in Japan.

Koike Issey Miyake was the first person who foresaw the importance of a design archive and spoke out about it. He said that he started the archive as a will to preserve the identity. That's why it's important. At the same time, Mr. Miyake said that he wanted to create a design museum in Japan. This is based on the same will. At present, powerful designers keep their own archives as far as they know, but I think that many of them do not feel like commissioning or donating them to the Japanese government. If there were such a solid design museum as Mr. Miyake had envisaged, I think everyone would be happy to donate their work.

ー You were the director of the Towada Museum of Contemporary Art from 2016-20, which opened in 2008 as a base for urban development projects. It was designed by Ryue Nishizawa. It is a unique museum where the works are displayed in a way that is open to the city. Do you think it is possible for a public museum with such a new concept to establish an archive activity?

Koike First of all, it would be difficult. I don't think it is possible for a local government in Japan to make a policy on design, unless it is a rare case that the prefectural governor has a cultural officer as his right-hand man. Museums have permanent collections, but they are only collections, they don't have archival ideas. The fact that contemporary art is transitory makes it even more difficult to think of it as an archive.

However, when it comes to fashion, the Iwami Art Museum in Shimane has one of the largest collections of clothing in Japan, and together with the Kobe Fashion Museum, forms an important archive of clothing. I think there is a possibility for local governments to do the same. The Utsunomiya Museum of Art, which Mitsuo Katsui was deeply involved in, also has a collection of historical design works such as products and graphics, with the main pillar being "Life and Art". It would be a good idea to talk to the curator, Yuko Hashimoto.

ー The archive also includes the background in which things are created. I would like to ask Ms. Hashimoto about how this is preserved in museums. However, there is a huge amount of material and works in museums, and the material that traces the essence of the work is often discarded. What do you think is the first step to preserve such archives?

Koike I think the first step is for everyone to raise their voices and move the authorities. In this sense, the activities of PLAT are very important. Basically, the government should create a budget for archives, but it will be difficult to do so in Japan unless the Agency for Cultural Affairs becomes an independent Ministry of Culture instead of being under the Ministry of Education. In 1988, I participated in a Franco-Japanese cultural summit, and I was astonished to see the difference between France and Japan in the way the French government had a clear cultural policy and invested a huge budget to promote culture. That gap is still growing today, and there is a huge difference in the understanding of culture at the top of the country.

ー In Japan, design has been seen as an economic activity, and I think this is one of the reasons why it is left out of cultural policies. Lastly, I would like to ask you about the field of art and design. At the Tokyo Biennale 2020/2021, of which you were the general director, art was scattered all over the city and we were able to experience art in the real world. From the point of view of daily life, it feels similar to design, but for you, are the fields of design and art connected?

Koike It is a question that has been running unanswered since I started work in the 1960s, and even now there is no clear answer, but what is clear is where the initiative lies. What comes out of an artist can have an anti-establishment message or a strong poison in it, but the expression that comes out is art. Design, on the other hand, is something that fits into social systems, economies and organisations. However, this is what I think of as a characteristic, and in simpler terms, it is for the viewer to decide. Some see a great work of design and feel it is art, others see an artist's work as design-like. I believe that the sensibility of the viewer is increasingly important.

ー Thank you very much for this extensive and in-depth talk on archives. Thank you very much.

Enquiry:

Sagacho Exhibit Space

3331 Arts Chiyoda https://www.3331.jp/floor/b110.html