Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Hiroshi Kojitani

Graphic designer

Date: 27 September 2019, 14:00 - 16:30

Location: Office PLAT

Interviewees: Hiroshi Kojitani

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Aia Urakawa

Author: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Hiroshi Kojitani

Graphic designer

1937 Born in Nara Prefecture

1957 - 59 Worked for Hayakawa Yoshio Design Office

1959 - 66 Worked in the publicity department of MATSUYA GINZA

1967 – 70 Worked at Delpire Studio, Paris, France

1972 Founded and presided over Kojitani & Irie Design Office

1993 Founded and presided over K-Plus

Awards: Incentive Award of the Japan Advertising Artists Club; the Japan Sign Design Association Award, Gold Prize; the Minister of International Trade and Industry (now Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry) Award, the Asahi Advertising Award, the Mainichi Design Prize and the Dentsu Advertising Award. Also awarded the title of "Chevalier" of the Order of Wine of Bordeaux, Burgundy and Champagne, "Honorary Sommelier" of the Japan Sommelier Association, and the French Government's "Chevalier de l'Ordre des Services de l'Agriculture". Award for the promotion of tea ceremony culture.

Description

Description

Hiroshi Kojitani was one of those who saw and experienced the upheaval in the Japanese design world from the 1950s to the 1970s up close and personal. Until the 1950s, the Kansai region led the way in graphic design, but with the World Design Conference 1960, the mainstream shifted from Kansai to Tokyo. After the TOKYO 1964 Olympic Games and the Japan World Exposition, Osaka, 1970 (Osaka's Expo '70), Japanese graphic design flourished even more significantly as a result of exchanges with other countries. Kojitani studied under masters such as Yoshio Hayakawa, Ikko Tanaka and Hideo Mukai, and honed his skills in design offices in Tokyo's MATSUYA GINZA and Paris. After becoming independent, he developed a diverse range of designs that paved the way for a new era. Through his friendship with Ikko Tanaka, he joined Seiji Tsutsumi, Kazuko Koike and others as a founding member of MUJI, where he came up with product concepts that proposed a new lifestyle, designed logos and developed ethical and simple packaging designs.

Meanwhile, while living in Paris, he became aware of the delicious taste of wine, introduced Beaujolais Nouveau to Japan and established the "NPO Japan Wine Lovers Association". In recent years, he has also produced glass works and held solo exhibitions. We spoke to Kojitani, who is active in a wide range of fields, about valuable stories from the design world at the time, as well as the birth of MUJI, episodes with Ikko Tanaka and his own archive.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Poster

MUJI (1980-)

Shiki Theatre Company (1984-)

Package

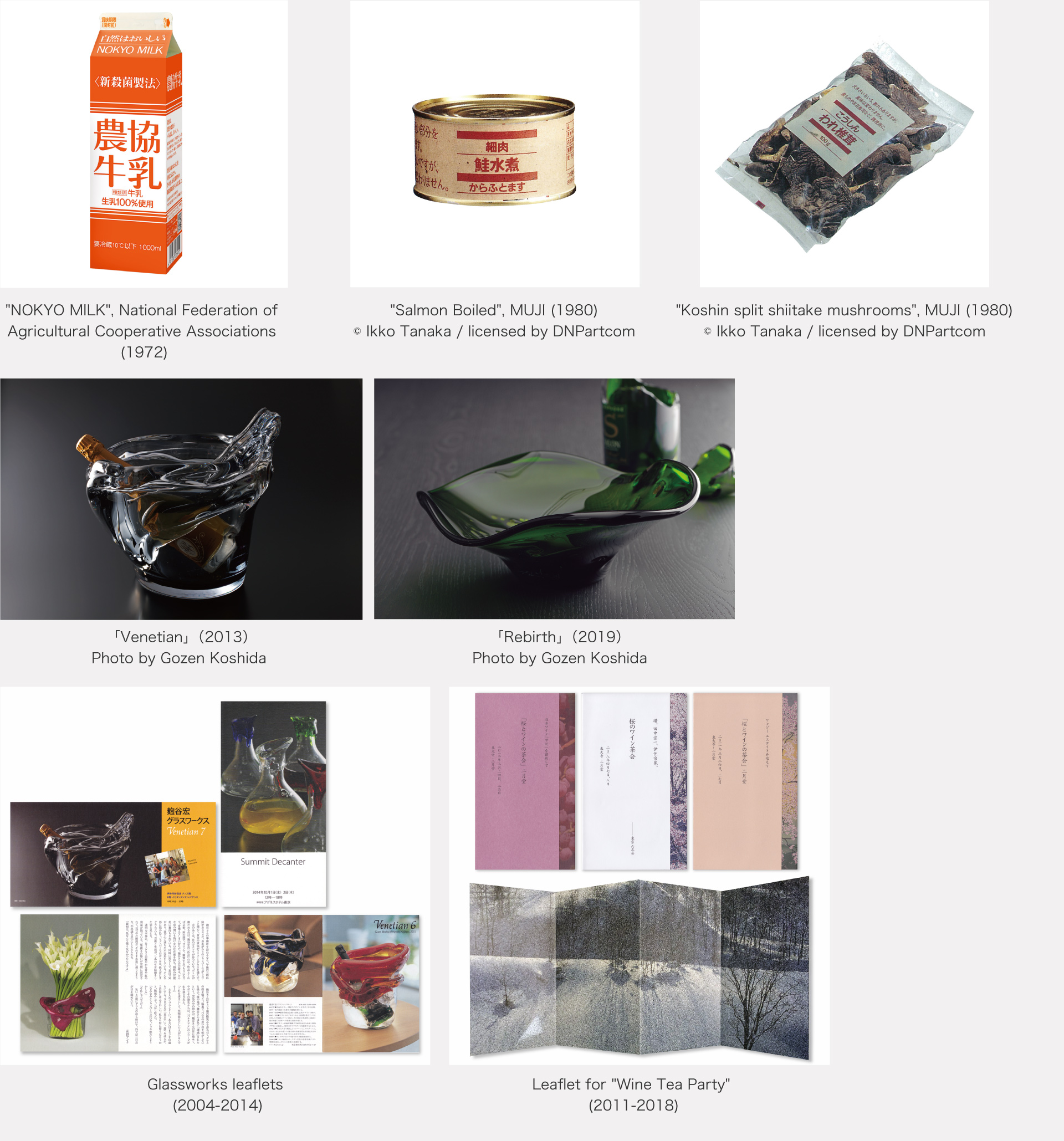

"NOKYO MILK", National Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations (1972)

"Salmon Boiled", MUJI (1980)

"Koshin split shiitake mushrooms", MUJI (1980)

Photographic works

"CATS", Shiki Theatre Company (1984)

Interview

Interview

Leaving behind an archive is important

Meeting Ikko Tanaka

― How did you first become interested in design?

Kojitani I did not originally aspire to be a designer. My family still runs the Kojitani Studio in the Kintetsu Nara Station shopping street, and I vaguely thought that since I was the eldest son, I would probably take over the business.

I was born in Nara in 1937, before the war. I entered a local junior high school in 1950, after the war. Science studies did not suit my body, so I enrolled in a preparatory school for high school, but when I entered, I was astonished to find that my classmates were all geniuses and brilliant students from all over Nara Prefecture. The only part of my school life that I enjoyed was the cultural festival, where I was good at organising events, bringing people together and conducting a theatre performance or a music concert.

Usually, I was always scolded by the teachers. In the middle of my first year of high school, I felt like I was hopeless and told my father that I didn't want to go to school, to which he replied: "If you don't want to go that badly, you don't have to go". I think my father also thought that I should take over the photo studio in the future. He told me about an art school in Osaka called Kogei Senior High School. It was a time when the word "design" had not yet been coined, and I chose the design department. At the preparatory school in Nara, I was scolded no matter what I did, but at this art school in Osaka, I was praised for doing something different, and my world changed completely. That's when I was awakened to design. In the midst of these happy days, I heard from some of my classmates that there was a genius in Nara called Ikko Tanaka, and I felt somewhat proud.

― While attending that art school, did you decide that you wanted to pursue a career in design?

Kojitani No, but I still thought that I would take over the family business after graduating from school. However, one day, one of my design teachers asked me if I would like to work in Mr. Yoshio Hayakawa's office, where he was looking for an assistant. Mr. Hayakawa was like a god in the world of graphic design, and he was also a senior student at my alma mater, Kogei Senior High School, Osaka. When I talked to my father about it, he said, "I don't have such a good offer, so why don't you just meet him", so I took the exam, passed it without a hitch and ended up working in Mr. Hayakawa's office.

It was about three months after I joined the office. A man in a sober navy blue suit, carrying a furoshiki wrapper, who looked like an insurance diplomat, came to the office and asked, "Mr. Hayakawa, are you there?" When I replied that he was out for a moment, he said, "Okay" and left. When I told my senior colleague that an insurance salesman had just arrived, she was surprised and said, " Oh no, you don't know him, that man is Mr. Ikko Tanaka".

When Mr. Hayakawa returned to his office, she immediately told him that I had mistaken Mr. Ikko for an insurance diplomat, and they laughed hysterically. Mr. Hayakawa immediately called Mr. Ikko and told him about it. I thought that if Mr. Ikko scowled at me because of this mistake, my design life would be as good as gone. As I was feeling down, Mr. Ikko came to our office again that evening and asked me, "Is that him?" And then he looked at me and laughed hysterically. For some reason, Mr. Ikko found me amusing and said, "Let's go back to Nara together" and we ended up having a drink at a shop on the way home. I was extremely nervous and I don't remember what we talked about. Since then, Mr. Ikko has treated me well in many ways. He is seven years older than me, so he was like a mentor and a big brother to me.

― Many graphic designers are from the Kansai region, with Mr. Ikko and Mr. Kojitani from Nara and Mr. Hayakawa from Osaka.

Kojitani In the 1950s, the Japanese graphic design world was led by the Kansai region, including Osaka, Kyoto and Kobe. In addition to Mr. Toru Sawamura, Mr. Yoshio Hayakawa and Mr. Ryuichi Yamashiro, Mr. Toshihiro Katayama, Mr. Tsunehisa Kimura, Mr. Ikko Tanaka and Mr. Kazumasa Nagai were known as the Four Young Kings. The World Design Conference held in Tokyo in 1960 was a major epoch-making event for the Japanese design world. It was an opportunity for designers from the Kansai region to move their bases to Tokyo, shifting the center of design from Kansai to Tokyo. Mr. Ikko moved to Tokyo in 1958 and I followed him to Tokyo in 1959.

Design activities in Tokyo and Paris

― Did you become independent after you came to Tokyo?

Kojitani No, I first joined MATSUYA GINZA. Mr. Hayakawa introduced me to Mr. Yusaku Kamekura if I wanted to go to Tokyo, and Mr. Kamekura introduced me to MATSUYA GINZA, where Mr. Hideo Mukai was working. Mr. Mukai was the first person in Japan to establish the job of Art director, which involves the overall direction of graphics, photography, copy and video. He started his art direction work while working in the advertising department of Sapporo Breweries. Gradually, his work was recognised by the Tokyo Art Directors Club (ADC), and Mr. Mukai was taken on by LIGHT PUBLICITY, establishing a full-fledged art direction genre.

― At the time, department stores were a coveted profession for designers.

Kojitani MATSUYA GINZA was confiscated after the war and turned into a department store for the Occupation Forces, and even after it was returned to Japan, it retained its western atmosphere and carried many modern and stylish design products from abroad. Around the time I joined the company, the Good Design Corner was established, selling Scandinavian furniture and gaining a reputation. Takashimaya had an outstanding sense of window displays, and Mr. Yamashiro directed the design of newspaper advertisements and posters.

There were no full-page advertisements in the newspapers at that time, and MATSUYA GINZA had the opportunity to produce a 10-page advertisement once or twice a month, which was so exciting that I couldn't sleep at night. Newspaper advertising at that time was one of the few places where design culture could be presented to society, and gradually I began to win awards such as the ASAHI ADVERTISING AWARD, the Dentsu Advertising Awards and the Mainichi Design Prize, and the variety of awards increased. I also produced a variety of other things, such as train hangings, posters for train stations and DMs. There were so many jobs that required design, and I was so absorbed in design that I only went back to my flat to change clothes.

― What made you decide to go to Paris after that?

Kojitani Around the time of my sixth year, I decided it was time to see design from around the world, so I attended the International Design Conference Aspen in Colorado, USA. After returning to Japan, I didn't go back to MATSUYA GINZA, but stayed at Mr. Ikko's home for a while, but as I wasn't getting any work and was hanging around, Mr. Ikko couldn't see me and introduced me to a design office in Paris. Later, an acquaintance introduced me to the Delpire Studio and I did a lot of work for major companies such as Citroën, Prisnick and BNP Bank. I was in Paris for about four years.

― What did you learn from working in Paris?

Kojitani I don't know if it was a learning experience, but I had a strong culture shock. Europe is a huge melting pot of different races, languages and cultures. The atmosphere created by this soil was very interesting, but the graphic design and communication design work, in which I had to assert myself, made me sweat and cold sweat every day. It was a turbulent time in world culture, with the student demonstrations at the University of Paris, the general strike that spread throughout France, de Gaulle's victory and resignation in the May Revolution, and the supersonic aircraft Concorde and Apollo 11 landing on the moon. I was in Paris, the heart of Europe, where I learnt how important international sensibilities and sensitivities are.

― When did you return to Japan?

Kojitani I temporarily returned to Japan in 1970, when the Osaka Expo was being held. I decided to return to Japan because Mr. Ikko asked me to help with the production of the official guidebook for the Osaka Expo. When I returned to Japan, I was surprised. The world's design information was gathered not in New York, Paris, London or Milan, but in Tokyo, and I realised that if I wanted to continue working in graphic design in the future, this meant I should stay in Tokyo. So I went back to Paris again immediately, left the Delpire Studio, cleaned up my Parisian life and came back to Tokyo.

At first I stayed at Mr. Ikko's home again, but after a while I rented a room in a flat in Nanpeidai, Shibuya, and started doing freelance work. Mr. Kensuke Irie came to help me at that time. He was a junior colleague at MATSUYA GINZA and we were good friends from that time. Mr. Ikko told me that it was time to start a proper company, and Mr. Irie wanted to quit MATSUYA GINZA and work with me, so we set up a company under the name Kojitani & Irie Design Office. That was in 1972.

Work for "NOKYO MILK", MUJI and the Shiki Theatre Company

― Your work since becoming independent is widely known as the package design for "NOKYO MILK".

Kojitani Soon after I returned to Japan, the Nokyo (National Federation of Agricultural Cooperative Associations) decided to enter the milk market anew and asked me to design the packaging. There I drank all the Japanese manufacturers' milk again and wondered why it didn't taste so good compared to French milk. I found out that cows lose weight and become low in fat in summer and gain weight and the milk fat content increases in winter, but the reason was that in Japan the low fat figures in summer are legally adjusted so that they are the same all year round.

I suggested to them that this was not the right way to go about it and that they should deliver milk with its natural, unadjusted taste. For the packaging design, the other company's packaging was so glamorous that they wanted me to go beyond that with a flashy, glittery, French-style design. However, I insisted on a simple design, saying that I preferred to evoke an image of nature, with the smell of earth and grass. It must have been difficult for them, but it was also hard on my stomach. The product name was also straightforward, emphasising the funkiness of "NOKYO MILK". Also, at that time there was no such thing as a message on the packaging other than the name of the product, but I included two words: "nature tastes good" and "ingredient-free". The product was launched in 1972 and became a long-seller lasting more than half a century. In hindsight, I think this work was rooted in the spirit that would later lead to MUJI in terms of establishing the product concept, omitting waste, and organising information and making it graphic.

― The MUJI project was born around Mr. Ikko Tanaka, Mr. Kazuko Koike and Mr. Kojitani -what was the initial impetus?

Kojitani One day, Mr. Ikko and I were approached about a magazine project, and Creative director Ms. Koike joined us, and I think the sponsor was SEIYU, of which Mr. Seiji Tsutsumi was president at the time. That project eventually died out, but we had lots of ideas for editorial themes and articles, so the four of us met often. At that time, from the late 1970s to the early 1980s, the foreign brand licence business was flourishing, and brand logo marks could be attached to anything, which added value to the product and made it more expensive, even though it was not of high quality. Are we talking about the frustrations and criticisms of that bubbly era, and when we looked into the background of things we had previously questioned from that perspective, we found a lot of things that made us gasp. For example, Mr. Tsutsumi wondered why shiitake mushrooms for year-end and mid-year gifts were packaged in the same size and beautifully aligned. When he looked into it, he found that only the beautiful ones are selected and packed, and those that are chipped or broken are discarded. Shiitake mushrooms are chopped and used in cooking, so there is no need for them to be well-shaped, and even if they are misshapen, the taste will not change. The values of the time when it was considered good to have such a uniform appearance have continued to be produced one after another, without being questioned.

― I remember when MUJI first started selling unripe shiitake mushrooms. You were involved in all MUJI projects, from the ideology as well as the design of the products.

Kojitani That was the most important point. Being a good product despite being MUJI was the same stance as that of "NOKYO MILK", which insisted that nature tastes good. It was design before design. When that happens, this is no longer simply the designer's job. What is it? A chance meeting led to the launch of a project, and product creation began in earnest. It was made possible because Mr. Tsutsumi, a businessman, happened to be at the table, and if it had been just us designers, it would have ended up as a mere complaint of the times.

― How was the name MUJI decided?

Kojitani We decided on "Mujirushi" right away, and "Ryohin" was suggested as the word to follow it, but it was difficult to decide because we thought that would be too heavy a reading. In the end, however, it was decided that it was good because it sounded good and the concept was easy to understand at a glance. As for the design of the logo, we originally thought that the product had no need for a logo due to its origins in the philosophy and spirit of the anti-brand logo. However, when I designed the first poster to launch the product, I decided that a logo was still necessary to announce the MUJI product. I told Mr. Ikko that I thought it would be best to use the most neutral newspaper type, so I decided to use Gothic letters, and he agreed with me that this was a good idea. At first, the type from that newspaper was used as it was, but then Mr. Ikko said he would sort it out, and the straight sections were straightened out, and the sections facing downwards at an angle were also straightened out. So I think the credit for the logo design goes to the Art director, Mr. Ikko Tanaka.

I then suggested that, as was the case with "NOKYO MILK", the reason why the product is good quality should be stated on the packaging. I also decided that the contents should be visible from the outside as much as possible, without excessive design and without superfluous packaging, and I created the prototype for packaging design that has led to the present day.

― What was the design fee for the logo, for example? When we asked others, they said they had never seen a contract.

Kojitani I did not receive any design fees. We come up with plans for this and that from chatting with each other, so there is no one to place the order. I thought it would be good to have a logo like this, so I came up with it on my own. After about 10 years, a board was formed and the first members became advisors. I left the MUJI job when I retired about ten years ago.

― I would like to ask you about another of Mr. Kojitani's masterpieces, the posters for the Shiki Theatre Company. What prompted you to work with them?

Kojitani "CATS" premiered in Japan in 1983 to great success and they decided to produce a photo book for the first anniversary the following year, which I was given the task of art-directing. I tried various creative ideas, such as looking down on the stage from a high vantage point and photographing only the stage set without any people on it. The finished product was so well received that Mr. Keita Asari, founder of the Shiki Theatre Company, liked it so much that he began to receive advertising and poster work from them. However, there were times when I could not get an OK even after submitting 10 or 20 design proposals. For The "Lion King", Walt Disney Company had very detailed rules and regulations, which were very strict and difficult.

Hideo Mukai's commitment to archiving

― I would like to ask you about design archives. Many graphic designers want to bequeath their work to future generations by donating it to universities, museums, etc. How about you?

Kojitani When I first started working in design, I kept some of the work I did for a while, but I never thought about doing something with it later. I think it is enough that the works that were widely introduced at that time are published in design yearbooks and other publications. That's because I've been working on advertising for a long time, and I've won awards and so on, and there are things that I think I've done well, but times go by quickly, don't they? When I look back, I still feel like it's an old event, an old memory, an old era. As for my own work, I wonder what the point is of leaving it behind. And if I keep them, where do I show them? If I do an exhibition, I want to show something new, not something from the past.

― In your work for the Shiki Theatre Company, you said that you submitted 10 or 20 ideas, but did you also discard the rejected ideas?

Kojitani In hindsight, it would have been interesting to keep it. Mr. Ikko, Mr. Makoto Wada and others were the type to keep them. Moreover, when someone says that thing at that time, it comes out in a flash. I am not at all interested in what has passed about myself. Of course, I think it is important to preserve the archives of the design world. After the dissolution of the Japan Advertising Artists Club in 1970 due to the student movement, it was decided that a professional association was still needed, and in 1978 the Japan Graphic Designers Association (JAGDA) was established, led by Mr. Yusaku Kamekura, together with Mr. Susumu Sakane and several others, including myself. The name "JAGDA" was proposed and decided upon by me. At that time, I proposed that the archive should be left behind, but it still didn't work out.

― What will you do with your own archive in the future?

Kojitani My archive is completely meaningless and unnecessary. I think there are more people who would be better off doing that. What I found particularly strange was that there was nowhere to accept the work of Mr. Hideo Mukai, one of Japan's leading Art directors. I thought that Mr. Mukai, who established the world of Art Direction in Japanese advertising design, was the one who had to preserve the archive, so I contacted every museum and university I could find. Most of the archive was held by his bereaved family and LIGHT PUBLICITY, but I felt that if this was not done, the paper would be damaged by newspaper advertisements and the works would be in danger of being scattered. But everyone was reluctant to do so.

One day, Mr. Kiyoshi Awazu introduced me to the newly built Kawasaki City Museum. When I met the director and heard his story, I realised for the first time that it costs an enormous amount of money to manage and maintain such an archive. I heard that it costs a lot of money to preserve even a single newspaper advertisement. However, he said that Mr. Mukai was a special person and agreed to accept the archive. I hope that in the future, the archive will be used as the basis for exhibitions and research groups.

― You worked hard to find a recipient for Mr. Mukai's archive, didn't you? This is the first time I have heard of a designer making an effort to find a recipient for a designer's archive.

Kojitani He is my benefactor and mentor. Mr. Mukai's work is an important advertising cultural heritage of the times.

― Mr. Kojitani, as well as design, you are also energetically involved in making glass works, wine and tea, all as part of your creative activities.

Kojitani I started making glass works from upcycled waste wine bottles in 1995, and in 1998 I founded and presided over the men's tea group "rosshikai" to propose new ways to enjoy the tea ceremony. For the Kyushu-Okinawa Summit 2000, I created a glass decanter for the Head of State Dinner. Although I retired from graphic design in 2009, I continue to make glass work and have held solo exhibitions.

In a word, my glass work is my love for wine. I first discovered the taste of wine in Paris. I thought it was a pity that wine bottles are thrown away when they are finished, so I came up with the idea of using waste products and transforming them into new works of art. Everyone said it was interesting and that was enough for me. I don't think about bequeathing my glass works to posterity as an archive either.

Anyway, every day I play around as I please, looking for something different and interesting to do. I still call myself a Graphic designer for the sake of convenience, but now I am just a playful person and I am very happy and stress-free.

― I look forward to seeing your new work in the future. Thank you very much for your time today.

Enquiry:

K-Plus

http://www.kojitani.jp