Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

河野鷹思

グラフィックデザイナー

Interview01: 12 May 2022, 13:30-15:30

Interview02: 24 June 2022, 13:30-14:30

Interview03: 7 July 2022, 14:00-15:00

PROFILE

Profile

Takashi Kono

Graphic designer

1906 Born in Kanda, Tokyo

1929 Graduated from Tokyo Fine Arts School (now Tokyo University of the Arts), Department of Design. In the same year, joined Shochiku Kinema (now Shochiku) and was assigned to the Advertising Department.

1934 Joins Nippon Kobo (second phase).

1936 Establishes Atelier Kono.

1941 - Served in the Pacific War, interned after the war and returned to Japan in 1946.

1948 Worked as a contract art director at the New Toho Film Studio

1959 Establishes Deska

1964 Member of the design committee for the 18th Olympic Games in Tokyo

1970 Exhibition designer, Japanese Government Pavilion, Japan World Exposition

1976 Awarded the Order of the Rising Sun, Fourth Class

1992 Awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Third Class

1999 Passed away

Other

Participated in the founding of Japan Advertising Artists Club (1951). President of the International Jury of the Warsaw International Poster Biennale (1968). First Japanese member of the Royal Society of Arts (1983).

Taught at Musashino Art University, Joshibi University of Art and Design, Tokyo University of the Arts and Aichi University of Fine Arts, and served as President of Aichi University of Fine Arts from 1983 to 89.

Description

Description

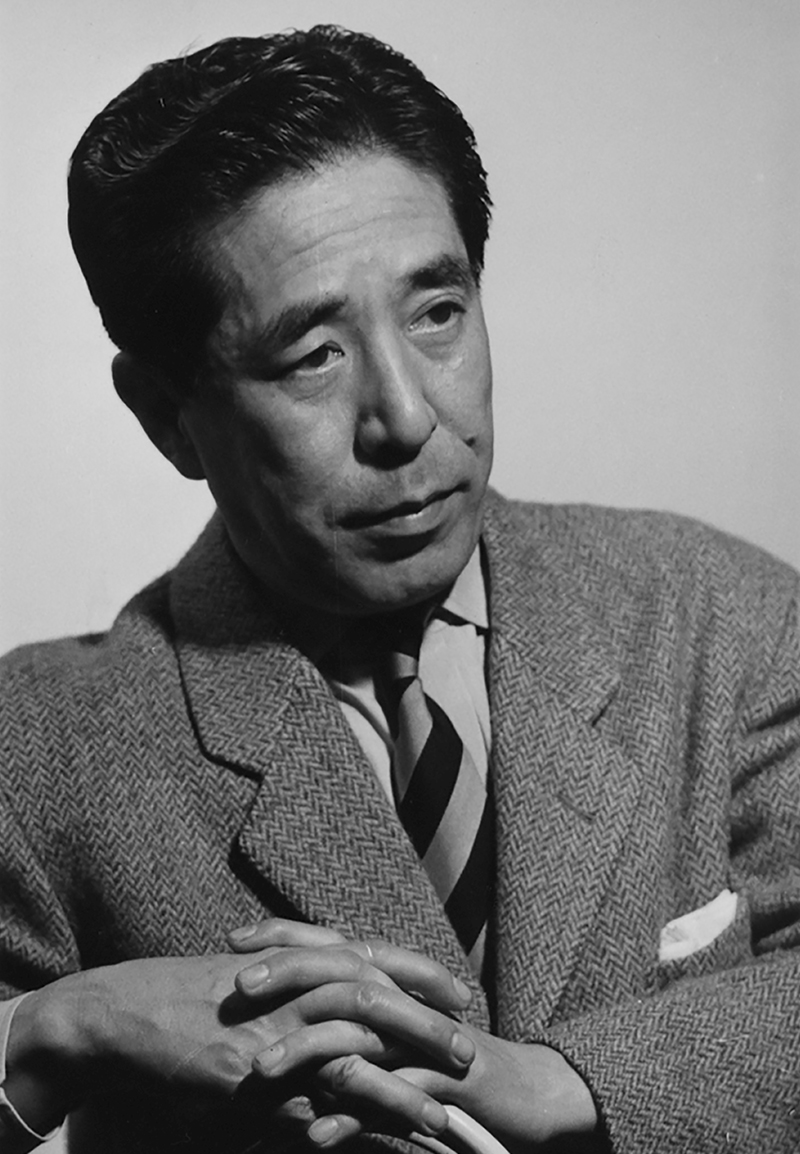

Kono Takashi is a designer who represents the dawn of Japanese graphic design. Yamana Ayao, who created the foundations of Shiseido design by arranging Art Deco in a Japanese style; the theorist Hara Hiromu, who left his mark on typography and book design; and Kono Takashi, who established his own world by combining Western modernism with the stylishness of the Edo period. In pre-war Japan, these highly individualistic individuals cultivated the soil of graphic design.

Kono's first steps as a designer began as a member of the advertising art staff at Shochiku Kinema (now Shochiku), after working on stage sets at the Tsukiji Little Theatre. There he was in charge not only of film and theatre posters, but also of stage design and props, showing his talent for designing in the three-dimensional world. Later, he joined Nippon Kobo, which was founded by the photographer Yonosuke Natori, and through the editorial design of the wartime foreign propaganda magazine NIPPON, he tried his hand at fusing photography and graphics. He was drafted into the army in 1941 and ended the war on the Indonesian island of Java, and after nearly a year as a prisoner of war, he returned to Japan in 1946 and made a comeback as a designer. He then established the general design office Deska and worked in a wide range of fields, from postage stamps to rug designs, hotel interiors, department stores' and exhibition displays, and public architecture concepts. As a leading figure in the design world, he played a central role as a member of the design committee for the Tokyo Olympics and the Osaka World Exposition, and also worked to improve the design world and t including founding Japan Advertising Artists Club, and serving on the executive committee of the World Design Conference.

Looking at Kono's work today, it is possible to read the insights and messages contained in his simple designs. In an interview with Arata Isozaki, Kono said of his expression, "(My style is) extremely simple, abbreviated, and what is called a design style". His signature poster 'SEHLTERED WEAKLINGS-JAPAN' has his unique satire, and is still fresh even 70 years later.

This time, 23 years after his death, we interviewed his daughter Sumire, his grandson Kyuichiro, who maintains the archive, and former Deska staff members Teruyo Shiina and Kenji Kaneko about the archive and Kono‘s personality.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Magazine advertisement, film 'The Lady and the Beard' Shochiku Kinema 1931

Magazine advertisement, film 'Young Inspiration' Shochiku Kinema 1932

Cover of foreign propaganda magazine 'NIPPON', Nippon Kobo 1940

Cover of the satirical magazine 'VAN', Evening Star 1946

Poster "SEHLTERED WEAKLINGS-JAPAN" Self-produced 1953/1983 (reproduced)

Poster "Tanko" Tankosha 1955

Poster "JAPAN" Self-produced 1955

Illustration "SAKANA" Self-produced calendar 1963

Tokyo Olympics official book "LES JEUX OLYMPIQUES DE TOKYO". Organising Committee of the 18th Olympic Games, Tokyo 1964

The first official poster. "XI OLIMPIC WINTER GAMES SAPPORO '72", the first official poster. Organising Committee of the 11th Sapporo Winter Olympics 1967

Symbol mark "Good Design Corner" Ginza Matsuya 1960

Symbol mark Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank 1971

Illustration 'Sakana' self-produced calendar 1963

Books

The Design of Takashi Kono" Nishikawa Shoten 1956

My Design by Takashi Kono, Rikuyosha, 1983

Takashi Kono’s movie poster, Seiki Shobo 1933

Interview 1

Interview01:Sumire Kono, Kyuichiro Kono

Interview: 12 May 2022, 13:30-15:30

Place: Deska

Interviewee: Sumire Kono, Kyuichiro Kono

Interviewer: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

Kono's work desk was always tidy.

He was fastidious about everything having to be straight.

Current status of Kono's works and document

― It is more than 20 years since Takashi Kono passed away. I understand that his works and materials are kept by his family.

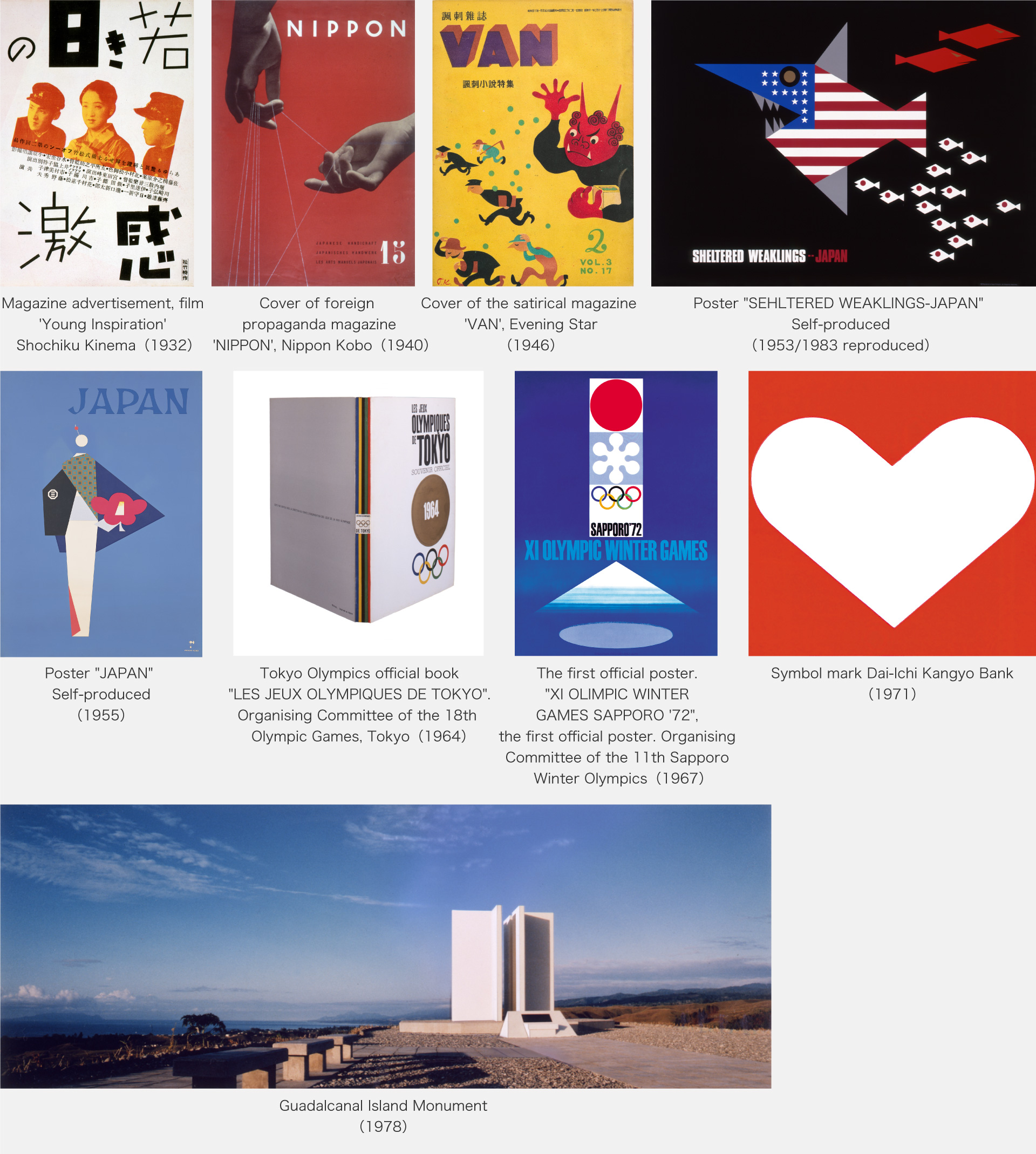

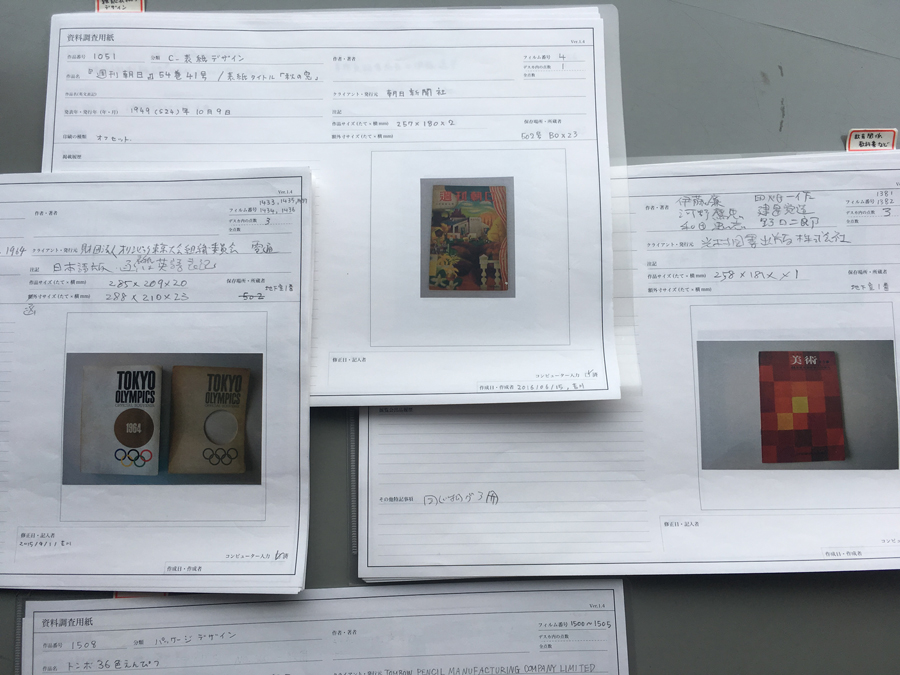

Kyuichiro The majority of them are kept here in Deska. We are working on this with the advice of experts. First, each piece of artwork or material is numbered, and the information is entered by hand on a special research form, after which it is digitised on a PC. The works are roughly categorised and stored as posters, books, photographs, etc.

― What prompted you to start the work?

Kyuichiro After my grandparents passed away, the publication of ‘Seishun Zue: Collection of Takashi Kono's Early Works’, supervised and written by designer Naomichi Kawahata in 2000, and the Great East Japan Earthquake, we had a sense of crisis. We recognised that the storage of our works and materials had been sloppy and asked for expert advice on how to properly store and organise them. The work was based on a list of artwork materials that Kono himself and his staff at the time had compiled during the production of ‘My Design, Takashi Kono’, published by Rikuyosha in 1983. We have also collected items as necessary, including those donated by several acquaintances. Items whose details are unknown at the moment are put on hold and updated as and when new information becomes available.

Handwritten survey form. A photograph of the work is attached and

data such as the name of the work, date of creation, etc. is written on the form.

The data is being input into a PC and converted into digital data.

― The book ‘Seishun Zue: Collection of Takashi Kono's Early Works’ is a very thorough account of Kono's pre-war and wartime career. It is also valuable as an archive.

Kyuichiro I am very grateful for the fact that it includes things that my family didn't know.

― Speaking of which, I was surprised to hear that during the new sorting process, a greeting card for Masayoshi Nakajo's first solo exhibition ‘Studio’ (1973), which was held at Gallery 5610, was found. Even Mr Nakajo himself didn't have it, but Mr Kono had it in his possession.

Kyuichiro We were also surprised. It is exciting to make various discoveries when organising the materials.

― What other items are in the collection apart from posters and books? Are there any preliminary drawings or handwritten sketches?

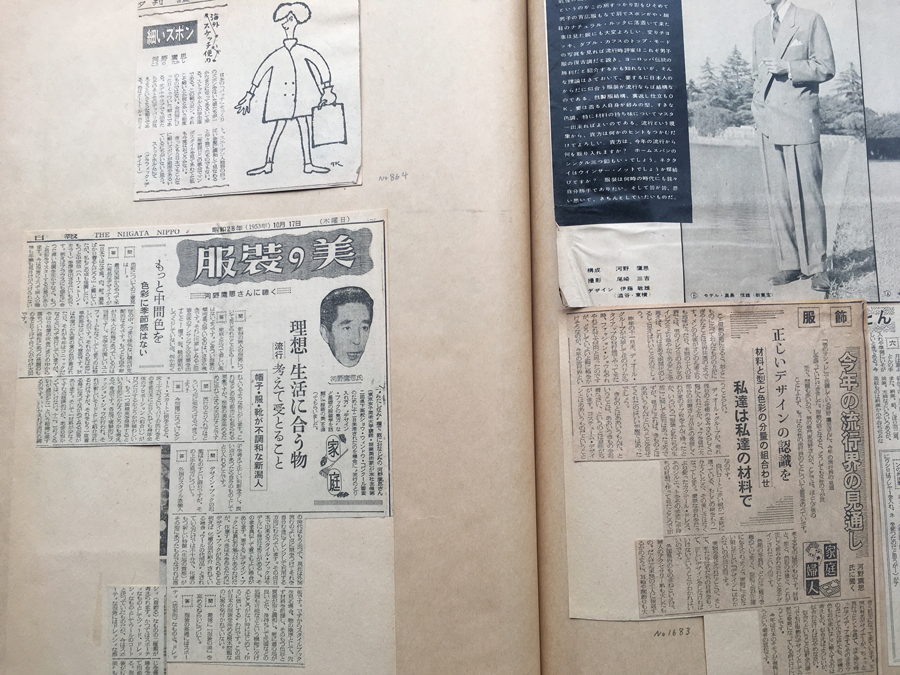

Kyuichiro Most of his work is in printed form, including posters, books and magazine advertisements. The material includes scraps of magazine and newspaper articles written by Kono, photographs, films and a very small number of handwritten manuscripts before they were printed. There are also very few autograph oil paintings and illustrations for book and magazine covers. In the past, once the original drawings were handed over to the printers, they were never returned, and Kono did not care for them, so many have been lost. For him, the printed matter was the work of art, and he probably had no intention of keeping sketches or notes of the production process.

― The same seems to have been true for Yusaku Kamekura. Having said that, it is a pity that no autograph drawings have survived. This is because, at that time, I heard that all the designs for the patterns and letters were done by hand.

Sumire When I started helping my father's office after I graduated from junior college, I saw my father designing the designs and letters and Toshihiko Morishita, a staff member, colouring them in along those lines. Mr Morishita coloured out the colours many times and got my father's approval each time.

― There were also handwritten manuscripts and esquisses in the scrapbooks, but there were almost no corrections, and the letters lined up straight and neatly on the paper without any squares. The handwriting shows his personality.

Scrapbook. Some of the scrapbooks contain newspaper and magazine articles compiled

from a wide range of perspectives, not only on design but also on fashion and customs.

― You have many essays on fashion and customs as well as design.

Kyuichiro Kono was also involved for a long time with the magazine " Soen" of the Bunka Publishing Bureau in collaboration with the photographer Sankichi Ozaki. He was asked to become the head of the office. During Kono's student days, he assisted to research with the study of modern social phenomena and worked on everything from stage sets to posters, flyers, tickets and costume archaeology at the Tsukiji Little Theatre. Although his main work was in graphic design throughout his life, he always considered the total design, from packaging, displays, bindings, stage design, costumes and monuments. He also wrote a lot about design, for example on interior and craft design for Japanese magazines when he toured Europe after the war under the guise of a design tour. This scrapbook contains a cross-section of his writings and articles from that period.

― What is the total number of materials at the moment?

Kyuichiro The detailed items are still being sorted out, but there are nearly 3,000 items. We have roughly categorised them by genre, such as posters and books, but there are many items for which we cannot determine the date of production.

Sumire We have organised them before, every time we moved, and we must have organised a considerable amount when we built this 5610 building in 1972.

― Poster works are collected by the Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art and other institutions, but what about Kono's works?

Sumire My father was active before the war, and many of his posters were used for advertising films and theatre productions, so they were thrown away when they were finished. When Shigeo Fukuda used to be a staff member of Deska,he asked my father to give him some of Kono’s posters from the office wall, and Kono said. “Okay”, and he gave them to Fukuda.

Kyuichiro After Fukuda passed away, it was discovered that they were stored in the Shigeo Fukuda Design Museum in Ninohe City, Iwate Prefecture. His works are housed at the DNP Cultural Promotion Foundation, Musashino Art University, Tokushu Tokai Paper Pam, National Film Archive Japan, MoMA (Museum of Modern Art, New York), Utsunomiya Museum of Art, Aichi University of the Arts, Printing Museum, National Diet Library, Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature, Kawasaki City Museum, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, Prince Chichibu Memorial Sports Museum, EXPO '70 Pavilion (formerly the Iron and Steel Pavilion), and the Tokyo University of the Arts, which has both graduation works and those of the current students. It has also recently been discovered that propaganda posters made for the Japanese military occupation policy in Indonesia during the war are in NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam.

― The heart logo of the Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank is well-known, and you have also designed for companies, Mr Kono. What about those materials?

Kyuichiro They are sorted by company and stored in boxes. However, they are the work of Deska, not Kono personally, so I am not sure whether I should keep them as personal works or not.

― Since they are the work of the office headed by Takashi Kono, we think it is safe to say that they are Kono's work. By the way, is it difficult to keep storing your works and materials?

Kyuichiro Yes. Ultimately, it would be ideal if they were stored in a specialised institution, but it doesn't make much sense for them to be stored in a warehouse as an archive, does it?

― Yes, that's right. In fact, there may not be many examples of archives being utilised.

Kyuichiro That said, we think it is important to preserve them. The archiving of materials, including scrapbooks, allows us to learn about the overall activities during their lifetime.

However, many people who knew about the old materials have passed away, and we sometimes regret that we should have asked about them earlier.

― We feel the same way as you about this activity.

Kyuichiro I hope you can see the storage conditions in the actual storeroom later.

One of the storage rooms. Books, magazines, posters, photographs, original drawings

and corporate materials are sorted according to their contents.

The works are stored in custom-made neutral paper storage boxes to prevent deterioration

and are indexed individually. The box for original artwork is clearly marked with a colour copy of the illustration.

Mr Kono from the family's point of view

― First of all, what was your father, Takashi Kono, like from your daughter Sumire's point of view?

Sumire I first saw my father at work after the Second World War, when I was in the third grade of primary school. My father was drafted to the end of the war on the Indonesian island of Java, where he spent time as a prisoner of war, and returned home about a year after the war ended. My family and I were evacuated to an inn in the fishing village of Mitakamura (now Kawazumachi) in Izu, shortly after my father's departure for war. He returned there.

My father's first job after the war was designing the cover of the general satire magazine "VAN". I heard that it was an invitation from the editor Ippei Ito, who had known him for a long time. At the time, he was working in a room at home, and I got to know my father's working style by watching him. Tools for design were scarce, and my father worked very hard on our study table, using drawing paper he had bought from somewhere and waterproofed it.

After a while, my father had more opportunities to go to Tokyo for work, and we moved first to Ito and then two years later to Kouzumachi (now Kouzu, Odawara, Kanagawa Prefecture) as it was an easier commute. The house in Kouzu was an annex on the grounds of the villa of photographer Yonosuke Natori's father. It was a Western-style structure with a large veranda and Western-style toilets, but there was no kitchen, so my mother had a lot of trouble. It was a very typical choice for my father, who had lived in a Dutch building in Java. At this time of the year, we had separate workplaces and kept work and home separate.

― His work steadily increased. "VAN" was a magazine in which many cultural figures of the time took part, and was a satirical magazine that looked at the movement for democratisation under GHQ from the perspective of various events in the world. According to the biography of Kensuke Ishizu, it is written that the VAN jacket brand, which dominated the market, was named after this magazine.

Kyuichiro In addition to VAN, my grandfather also did bookbinding and illustrations for magazines and books published by the same Evening Star company, as well as covers for "Shukan Asahi" and "Sunday Mainichi", and seems to have returned to work in theatre and film art, which he had been connected with before the war. For example, the original oil painting on the cover of "Shukan Asahi" in this scrapbook is an oil painting, but at the time there were two printing houses, one in Tokyo and one in Osaka, and he drew two exactly the same pictures and submitted them to each. Even though copying machines did not yet exist, it is surprising that two such complex drawings were completed at the same time.

― It could be said that it was a luxurious time when so much time and effort was spent on covers.

Sumire As a child, I remember watching my father draw this picture (in the scrapbook), and I was surprised and excited to see that the picture changed every day. The next time I saw the picture was when I found the cover of the "Shukan Asahi" in a bookshop, and I felt very proud. I used to boast to my friends, saying, "This is my father's design."

― Graphic design is hard work, with all-nighters being the norm, how was it for him?

Sumire I think he was very busy. When he was young, I heard that he was stuck in a can at an inn to finish his work. But he was very punctual. In later years, after we moved here to Aoyama, he would finish work in the evening, get dressed up and go to Ginza for a drink. Perhaps the reason he was so determined was because he wanted to go to Ginza for fun (laughs).

― This episode conveys the liveliness of the post-war period. Now, Mr Kono seems to have recovered his work from a room in his house after returning from the war, but did he encounter any difficulties?

Sumire My father was a man who was dedicated to design, so I think my mother (Mrs Shizuko), who was responsible for the accounting and miscellaneous tasks of my father's work, had a lot of difficulties. In the immediate post-war period, the house was both home and work place, so it must have been very difficult to adjust the environment, as one day the children's room suddenly became my father's work place.

After that, the workload gradually increased and the work environment was improved, and in 1959, my father and mother organised the office and established the general design office Deska. When creating the company, an acquaintance from the Yawata Works, where my father was working at the time, gave them advice. The unveiling party of the office was held in the lobby of a hotel located alongside the headquarters of the Yawata Works.

However, the office's work was messy in a good way, and my sister and I were sent out as models to design newspaper and magazine advertisements, because there was no money to hire models. For me, it is a fond and happy memory.

Kyuichiro During this period, my grandfather also did theatre-related work such as stage design and posters, but the design fees were small, so he often received stage tickets in return.

Sumire Thanks to that, I often saw the Haiyuza and Mingei plays, and I enjoyed them.

― He was a man of discipline, so he never brought his work home, did him?

Sumire No, he never did. I have very few memories of my father as a family man.

― Aoi (Aoi Huber Kono, eldest daughter of Takashi Kono), who still lives in Southern Switzerland and is active as a designer, illustrator and picture book author, was she influenced by her father?

Sumire My sister had said since primary school that she was going to Tokyo University of the Arts, the same university as my father, and she was also a good drawer. People around her also saw it that way. Masayoshi Nakajo worked at Deska for a while, and he was also my sister's drawing tutor.

― Aoi later went abroad, but did you ever try to work with your father after returning to Japan?

Sumire My father saw my sister as a designer and that is why my father and sister had differences of opinion about design and expression. On the other hand, my mother wanted my sister to come back to Japan and run Deska, but she had no intention of doing so.

― 海Atelier Niki Tiki, which introduces good toys from abroad, carries the famous playground equipment 'Animal Puzzle', which was designed by Aoi, isn't it?

Sumire My sister studied drawing with Toshiko Nishikawa, the founder of Niki Tiki.

― What kind of grandfather was he to your grandson, Kyuichiro?

Kyuichiro I have the impression that he was an interesting grandfather. I also liked drawing, so we used to draw together when I was a child. My grandfather was very quick with his hands, and he used old brushes and ink blotters at will, and in no time at all he had created drawings that were humorous and fun for children to look at. We also played catch and sumo wrestling. Then, here (at Kono's house in 5610), Masayoshi Nakajo, Shigeo Fukuda, Shu Kataoka, Joji Kimura, Hanmo Sugiura, Takeshi Tsuruta, Kotaro Maki in the stage design field, Saburo Ohba and his wife Kanako, a ballerina, often came and had a drink with my grandfather. I was sometimes allowed to sit in on these visits. When I went to Deska, they would leave me free to paint or look at books. I also watched my grandfather painting in oil, and I was very interested in his brushstrokes and his ever-changing colouring. His work desk was always tidy and he had a fastidiousness about everything that had to be straight. In other shops and hotels, if a picture or frame on a wall was even slightly tilted, he would tell them to make it parallel.

― Didn't he want Kyuichiro to take over the office?

Kyuichiro My grandfather used to study Japanese painting, but gave it up after his family's house was damaged in the Great Kanto Earthquake, so he was very happy when I started Japanese painting at high school. My grandfather always told me that designers are not hereditary, unlike traditional crafts, so I don't think he wanted his grandchildren to succeed him.

― Mr Kono was a person who drew his own pictures, composed his own screens and created his own typography. Did Mr Kono's influence have anything to do with the fact that many designers at Deska, such as Mr Nakajo and Mr Fukuda, were artistic thinkers and graduates of the Tokyo University of Fine Arts ?

Kyuichiro He was a lecturer at the Tokyo University of Fine Arts for a while, and I think that's how he got to know everyone. When he started as a company organisation, I think he borrowed their help to make it a general design office. Deska comes from Designers Kono Associates, so perhaps my grandfather wanted to specialise and divide the wide range of work that he took on.

― When you say Deska was at its peak, was that when Mr Nakajo and Mr Fukuda were there?

Kyuichiro In terms of the number of staff, it was a little later, after the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, and there were apparently close to 20 people on the staff. Including the cameramen and drivers, there was even an in-house baseball team.

A man of wide-ranging qualities and foresight

― I read Arata Isozaki's book 'The 1930s of Architecture: Genealogy and Lineage'. In this book, amongst a list of architects, Mr Kono is the only one to discuss a non-architectural field with Mr Isozaki on the subject of 'Culture of the 1930s from the perspective of commercial art'. I was also surprised to learn from the aforementioned scrapbook that Mr Kono has written essays on all cultural fields, including architecture, design, customs, overseas affairs and fashion, and that he is an erudite scholar.

I was also overwhelmed by the foresight of Mr Kono, who 50 years ago built the richly planted 5610 Building in the middle of Aoyama, where he ran a gallery in addition to his workplace and home. What does your family think of these broad qualities of Mr Kono?

Sumire As for 5610 Building, I don't think my father had a big vision from the start, but rather a combination of fortunate encounters and opportunities.

― This place is now an oasis in Aoyama - it was built in 1972, and I think he must have had some strong feelings about building such a luxurious building during a period of economic growth.

Sumire I heard that this was also a chance encounter. Originally, this area was a burnt-out area from air raids and was full of empty lots. At the time, there was a large sukiyaki restaurant called ’Iroha’ in the area where the Spiral Building now stands, and my father used to go there often to launch work with people from the film industry. One day, when my father asked the proprietress if he was looking for a plot of land in this area, she suggested that he use the land behind the restaurant, which was vacant. So my father and Tetsuro Hashimoto, a painter who was a close friend, bought half the land, my father designed and built a one-storey building and my family moved from Kouzu in 1950. My father used the large room next to the entrance as his workshop. Later, the land was combined into one, and in 1972 the current building was built. My father conceived the idea for the building and asked Takenaka Corporation to final design and construct it.

― The building is a luxurious space with a beautiful garden, a terrace where people can rest freely and a gallery. Did Mr Kono have an idea for public spaces, galleries and other cultural activities from the beginning in 1972?

Sumire I do not know details about the move and building construction, as neither of my parents gave me any details. However, I remember how sad it was that when they rebuilt the building, the one-storey wooden dwelling and four other buildings, including the office, were demolished so quickly and the wood was burnt in one day. It's hard to believe now that they burned them.

Kyuichiro It seems that the building-to-land ratio was stricter back then than it is today, and my grandfather must have built this building in compliance with it. In later years, I learnt that both my grandparents were dissatisfied with the lack of awareness of 'culture' in Japan. I think that's why they intended to create an art gallery and garden exhibition space in a part of their building to make it a cultural centre. It must be that 50 years have passed, the surrounding area has been almost completely rebuilt and today this building remains unchanged.

Oasis-like building 5610 in prime Aoyama location,

where exhibitions are also held in the gallery.

― I think the simple building with red bricks reflects the idea of modern design.

Kyuichiro The layout of the garden and the building, the shape of the balustrade, and the fact that they dared not to add a veranda so that the balustrade on the roof is not visible when looking up from below, seem to have been particular about minimising the unevenness of the appearance. In addition, a person from Daiwa Ceramics in Seto told us that the colour of the tiles went through a number of prototypes in order to get closer to the image specified by the grandfather.

― Mr Kono wrote in Takenaka Corporation's journal "Approach" that he thought of the building as a kind of collection of occupations related to his work, and it is wonderful that even 50 years later, Mr Kono and his family have passed on this idea.

Kyuichiro It can be said that this is a result of my grandparents’ relationship. Thank them very much.

― By the way, as an educator, Mr Kono was also a professor at Joshibi University of Art and Design, Tokyo University of the Arts and Aichi University of Fine Arts, and was very enthusiastic about fostering the next generation of artists.

Sumire One of his students when he was teaching at Joshibi was Ms Nishikawa of Niki Tiki. At that time, I think my father was one of the first to adopt the design ideas of the German Ulm and Bauhaus schools and utilised them in his educational practice. I have heard from Ms Nishikawa that he was influenced by my father.

― He also served as president of Aichi University of Fine Arts .

Sumire In his later years, my father also served as president of Aichi University of Fine Arts, and he said he wanted to move his base to Nagoya. Perhaps he wanted to distance himself a little from my mother, who had supported my father in both public and private life for many years, and wanted to be free.

Kyuichiro There were some teachers and professors including who were taught by my grandfather when they were student at Aichi University of Fine Arts, and I heard that they all went out drinking together in the evenings. He may have enjoyed a life with plenty of time and mentality.

― Thank you very much for the valuable stories that only your family can tell. We will talk to former Deska staff members about Mr Kono. Please continue with a tour of the archive.

Enquiry: About the Takasi Kono Archive

Deska/Gallery 5610 https://www.deska.jp/profile

Interview 2

Interview02:Teruyo Shiina

Interview: 24 June 2022, 13:30-14:30

Place: café in Sakurashinmachi

Interviewee: Teruyo Shiina

Interviewer: Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

Profile

Teruyo Shiina, translator of Peter Behrens' book and long-time teacher at Showa Women's University, worked as a part-time staff member at Deska for eight years from 1966 to 1974, working under Takashi Kono in design. Shiina first came into contact with Japanese design after returning from Germany. We spoke to her about how Kono design appeared to her.

Mr Kono taught me an attitude to life.

― Please tell us about how you and Mr Kono met.

Shiina I worked at Deska as a part-time staff member for eight years from 1966. It was in 1961, while studying in Germany, that I happened to see a magazine that featured the works of Mr Kono. It was the Swiss graphic design magazine ‘Graphis’, and his work was featured on eight pages. The design was a fusion of Japanese elements and modernity. I realised that there was such great designer in Japan, and I wanted to work for him. After returning to Japan, I was fortunate enough to be introduced to Kono by an acquaintance of mine, Takeshi Tsuruta, who was a designer at Mitsubishi Electric.

― Did you study graphic design in Germany?

Shiina By chance, I ended up studying graphic design. My family was in business and I was in the economics department at Keio University, but I didn't really fit in. Around that time, my sister, who had studied music in Germany after graduating from Toho Gakuen College Drama and Music, invited me to study design in Germany. I wanted to learn something beautiful, so I decided to go to Germany too. I studied Japanese painting as a child, so I studied a lot of drawing and German. Then I enrolled at Werkkunstschule Offenbach am Main in Hessen, where my sister was from. The German college was close to the teachers and students, and I enjoyed learning the basics of design in a full environment. After graduation, I worked for a advertising agency designing typography, and after six years in Germany I offered to study also Swiss design at the time with the renowned Josef Müller-Brockmann, but it was not possible. So I returned to Japan and was introduced to Kono, whom I admired.

― What did you feel about working for Deska?

Shiina I was a part-time staff member, so I joined Deska in a free capacity. Masayoshi Nakajo and Shigeo Fukuda had already left. There were people who had supported Deska for many years, such as Toshihiko Morishita and Hiroshi Ohki, as well as Yoshinori Katsurayama and Norio Takeda, who were in charge of space design. Many of Mr Kono's early works were illustrations in the vein of Komura Settai and Kono also designed stage sets and costumes. In the 1960s he did graphic works, Expo displays, department stores' displays and spatial design such as the interior of Villa Tateshina. He also designed for the Japan World Exposition Osaka, Sangetsu, TENDO, Mishima Foods and Daiichi Kangyo Bank. He also worked for Kawade Shobo (now Kawade Shobo Shinsha Publishers) and editorial design of textbooks for Mitsumura Tosho Publishing. One of the most impressive of these was the Dai-ichi Kangyo Bank logo, a simple and beautiful heart shape.

― What kind of person was Mr Kono to you?

Shiina Mr Kono is, after all, a cool and stylish person. I think this is because he grew up in Kanda, Tokyo, and had the temperament of a chirpy Edo (present-day Tokyo). He was both urban and traditional. He was a bit cynical, but he had a unique atmosphere that didn't make him sarcastic. He also worked in film and theatre design, but he was a dandy, like an actor. He was also internationally-minded and could speak English in that era.

I don't remember being scolded by him. He would point out the heart of the matter with a softly humorous irony. I was not emotionally involved, but I was convinced. He was usually out on business meetings, but when he came back he was working at his desk. I believe that he had an attractive personality, and through his relationships he was increasing his job opportunities.

― What did you learn from Mr Kono?

Shiina Mr Kono taught me an attitude to life. In my third year at Deska, I had to slow down my work due to childbirth. At that time, I was asked to become a part-time lecturer at the Division of Home Economics of Showa Women's Junior College, and I accepted. When I told Dr Kono about it, he said: 'Don't become a sensei-ya'. I thought these were teacher-like words and that I had received an important message. That message meant: 'Don't be satisfied with doing the same thing over and over again' and 'Be creative in your own way in the field of education'. I thought I should never get used to it.

I will never forget the words of Shizuko, his wife who co-managed Deska: "Deska is a graduate school". Mrs Shizuko was responsible for the management of Deska and she had a strict personality, but she was honest. I think she wanted to tell me that Deska was a place where we could continue our studies.

― What do you like about Kono's work?

Shiina I like his masterpiece poster SHELTERED WEAKLINGS-JAPAN in the sense that it expresses the temperament of him. The poster symbolises a small fish of the Japanese flag chasing after a giant fish that imitates the USA. I think it is a masterpiece, a humorous and ironic expression of the world of the time. And I like the cover of the Urasenke tea ceremony magazine ‘Tanko’. This is because it is a work that is typical of him, a fusion of Japanese culture and modernity.

― Do you still have a connection with Deska today?

Shiina I am still in contact with Kono's second daughter, Sumire, and her son, Kyuichiro. This year, it is 50 years since 5610 Building was completed, and just during my tenure, it was rebuilt and Deska moved to the nearby Minami Aoyama Daiichi Apartments for a time. He built it with greenery in mind, and I think it's wonderful that he has continued to do so.

― Did you find any differences between German and Japanese design when working at Deska?

Shiina I was called a 'German' in Deska [laughs]. Because I used to take the empty bottles and cans in the office to the liquor store and redeem them. Germans are thoroughly rational, so this kind of thing was common practice, but it was not the case in Japan. Then I struggled with typography in design. I had received my design education in Germany and worked in typography, so I was familiar with the alphabet. But I had to learn from scratch how to work with Japanese characters and series. I also had a tendency to spend too much time on each job, perhaps because of the German rigour I had acquired.

― Any special episodes about Mr Kono that you know?

Shiina It was the war memorial at the Guadalcanal Peace Memorial park by Mr Kono. When my son, who was stationed in Singapore, visited Guadalcanal, he happened to spot name of Kono on a panel of the war memorial and immediately made it known to me. It had been erected in 1981 as a memorial to the war dead of the Solomon Islands. Mr Kono was also drafted into the Pacific War and ended the war on the island of Java. Those who were active in design during the war were probably forced to be involved in some degree in the propaganda work of the Japanese military. In this sense, I believe that Mr Kono also had an extraordinary feeling about the war. Considering this background, I think once again that his masterpiece poster 'SHELTERED WEAKLINGS-JAPAN' expresses his deep thoughts.

― Thank you very much for your valuable talk today.

Interview 3

Interview03:Kenji Kaneko

Interview: 7 July 2022, 14:00-15:00

Place: Deska

Interviewee: Kenji Kaneko

Interviewer: Mr Kyuichiro Kono, Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki.

Author: Yasuko Seki

Profile

Kenji Kaneko, who worked on the symbol mark for three museums in Asukayama

(The Shibusawa Memorial Museum, Kita City Asukayama Museum and Paper Museum) and is currently active as a freelance designer, worked at Deska for 16 years from 1971 to 1987 after graduating from university. He honed his skills as a designer at there. In other words, he spent the latter half of designer Takashi Kono's life together. Here we spoke to Kaneko about his experiences at Deska.

Design is to organise

― Are you a student of Takashi Kono.

Kaneko Mr Kono was involved in the establishment of Aichi University of the Arts from 1966 and became a professor in 1968. I was a third-year student at the university, but Mr Kono was already a special kind of 'professor among professors', and as a student it was difficult to get close to him. He was a good-looking man himself, wearing a black blazer and a well-tailored pink shirt, and his whole body radiated aura.

In my second year, I was directly instructed by him on the subject of 'clocks', but I have little recollection of what specific guidance he gave me or what evaluation he gave to my design. However, I do remember staying up all night for three days before the deadline to finish.

― After graduation, you joined Deska?

Kaneko Yes. But there was a lot going on before I joined Deska. I wanted to work at Shiseido, but I was rejected. So I decided to work for an affiliate of Sangetsu, which manufactures wallpaper and curtains. However, when Mr Kono saw my graduation work (a huge 4 x 3 m pointillist work), he invited me to join Deska. To be honest, I was unsure. This was because at the time I thought that Kono was active as an artist and did very little commercial design. However, I couldn't give up my longing for Tokyo and decided to work at Deska.

― What kind of work did you do at Deska?

Kaneko When I worked at Deska, most of the staff had been replaced, construction of 5610 Building had started and it was time for a fresh start as New Deska. There were no senior staff to teach the newcomers, so I had to start work straight away. Most of my work was in graphic design, and I was in charge of corporate design for TENDO, Mishima Foods, Sangetsu and other companies, bookbinding, tapestries and rug designs. I also worked on exhibition displays, interiors for hotels and resort flats, and public buildings such as museums.

― What kind of communication did you have with Kono in the course of the project?

Kaneko It is a case-by-case basis. Sometimes Kono would come up with the idea and we would draw up the plans and drawings, and sometimes our ideas would be superimposed on the Kono's opinions. In both cases, we often discussed and decided on the direction of the project while it was still in rough form. Kono thought that there were many different ideas to design and never dismissed the staff's ideas out of hand as no good. Every job was checked by Kono and given the OK. Some people said, "Isn't Prof Kono already doing nothing?" But he checked every detail and sometimes finished the work before we, the staff, came to work.

― Are there any memorable incidents?

Kaneko When I was enthusiastically doing manual work such as making block prints, Kono said to me: 'You should leave such work to the block cutters. You should do work that involves more thinking with your head’. That is why I have made it a habit to think about design in my head, and even today, with the advent of digitalisation, I still place importance on first conceiving the idea in my head. In reality, however, Kono often didn't like the block prints made by the printmaker, so I would correct them (laughs).

― What did you learn from Mr Kono?

Kaneko He has the idea that 'organising is design, and simplicity is best', and I sympathised with that. Many people think that decorating or adding something extra is design, but it was fortunate that he and I shared the same view.

― From your point of view, what kind of designer is Mr Kono?

Kaneko I have heard that , " At Shiseido, designers are engineers and are different from artists". I think Mr Kono had a similar philosophy. Because he thought that a designer is a kind of engineer who creates designs towards the greatest common denominator. He said that "what is seemingly undesigned is what is truly designed".

There are many pre-war film posters that he worked on that make extensive use of hand-drawn characters and figures, but they all have a simple, modern design. At the time, hand-drawing was still the mainstream, but after the war, with the development of technologies such as transcription and photography, his graphic expression also changed. Although he sometimes adjusted his transcriptions by applying long or flat styles, he remained consistent in his policy that simplicity was best.

― What is your favourite Kono's work, Kaneko?

Kaneko The first work that I accepted the most was his representative work, the Fish Series. They all have a simple structure and balance, and the overall proportion is very beautiful. Curiously, many of his graphic designs, such as the 'Fish Series', can be quantified. In other words, the freehand lines could be expressed not as freeform curves but as a series of partial arcs. I was able to practise such graphic design at Deska and cultivate my sensitivity. Thanks to that, when the wave of digitalisation came to design, I was able to easily accept the PC as a tool.

― What did you find good about learning at Deska after becoming a freelancer?

Kaneko When I am confused about things, I think: How would Dr Kono thinks this? Then I go back to the starting point I learnt from Kono: 'Design is to organise'.

― 5610 Building, which was under construction when you joined the institute, is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Do you have any memories of it?

Kaneko Although not directly related to the project, the exterior brick tiles and the construction of the exterior walls left a lasting impression on me. The brick tiles were custom-made and fired in Seto on purpose. Tiler hand-laid them one by one. The tiler started at the back of the building first, and when they got used to the work, they put up the front side. The exterior walls were built at great expense, with the foundations dug several metres underground to hide the neighbouring buildings. I think it is this kind of attention to detail that makes building 5610 a special place. Mr Kono has been uncompromising in his design.

― Thank you very much for your time today.