Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

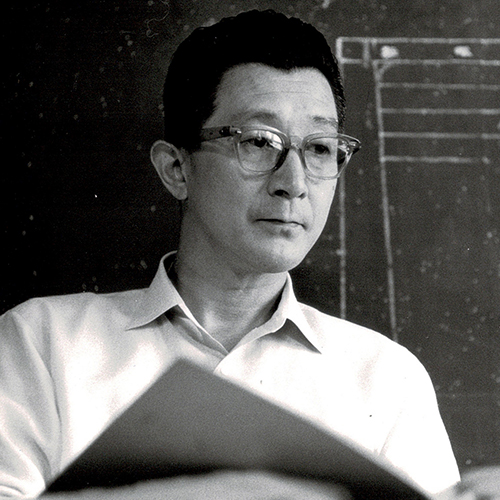

Jiro Kosugi

Industrial designer

Interview 01: 15 December 2023, 13:00-15:30

Interview 02: 10 January 2024, 14:00-16:30

PROFILE

Profile

Jiro Kosugi

Industrial designer

1915 Born in Tokyo

1938 Graduated from Tokyo Fine Arts School (now Tokyo University of the Arts), Crafts Department, Design Division

1944 Joined the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's Crafts Training Institute

1947 Establishes the Institute of Production Crafts with Iwao Yamawaki and others

1948 Invited to work for Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda)

1949 Works mainly as a freelancer

1952 Commissioned by Sanjo City, where he continued to provide commercial and industrial design guidance for hardware and other locally manufactured goods throughout his life

Kosugi Industrial Design Institute established

Established the Japan Industrial Designers Association (JIDA) (served as director and president)

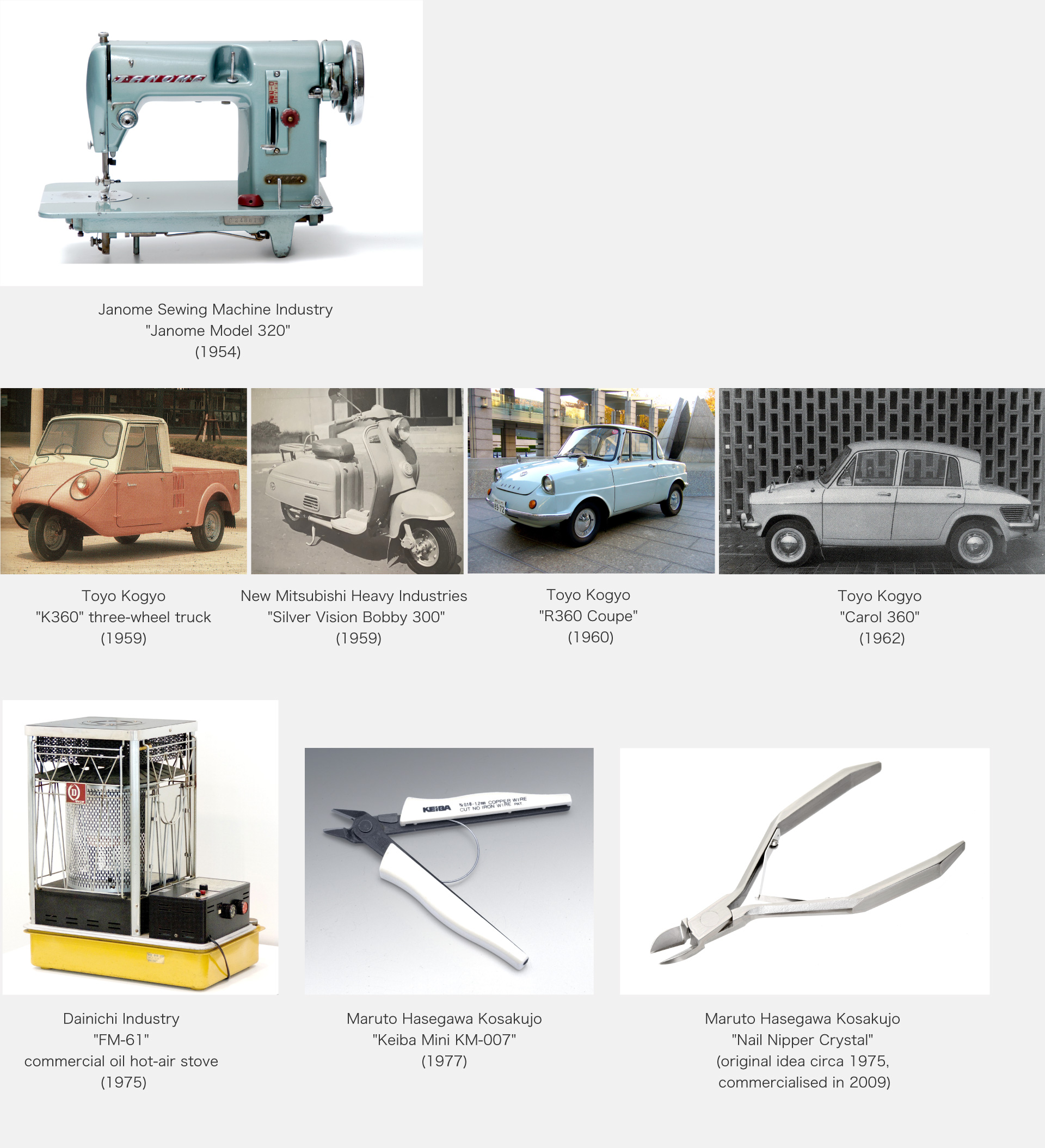

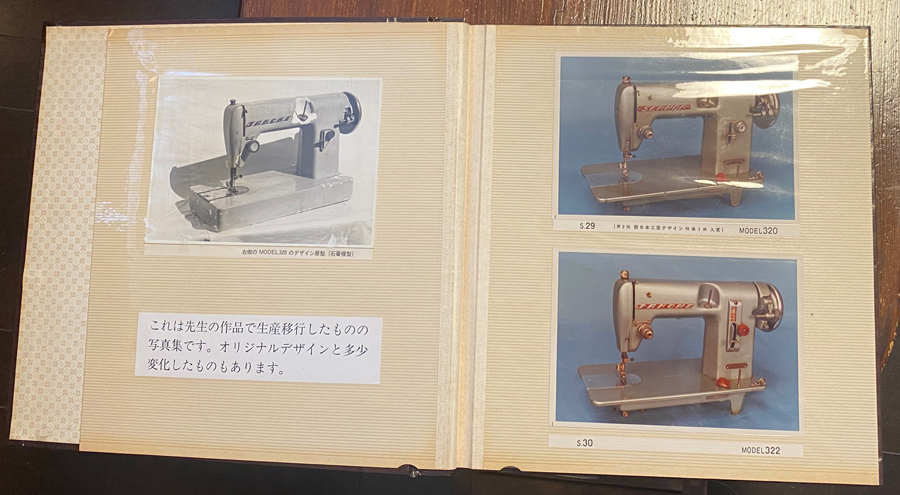

1953 First prize in the"2nd Mainichi Industrial Design Competition" for the Janome sewing machine

1955 Awarded the first Mainichi Industrial Design Award in the industrial design category

1957 Established Jiro Kosugi Industrial Design Laboratory Ltd.

1974 Honorary director of the Japan Industrial Designers Association

1981 Passed away

2019 Japan Automotive Hall of Fame Inductees

Description

Description

Pioneer of industrial design practice in Japan. He continued to work on industrial design until just before his death at the age of 65. A pioneering freelance designer, he was invited to work as a freelance designer for Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda), where he developed the auto tricycle and went on to create 16 cars under his own name, including the K360, the R360 Coupe and the Carol 360. At a time when designing in teams and groups was not established, he was an outstanding figure who could unite projects. He won first prize in the "2nd Mainichi Industrial Design Competition" for the Janome Sewing Machine Industry project, and since then he has worked on a number of the company's sewing machines. He was also commissioned as a designer by Sanjo City in Niigata Prefecture to provide guidance on the design of metalworking products, which became his life's work. His design work ranged from cars to stoves, fans, safes, scales, tools and nail clippers.

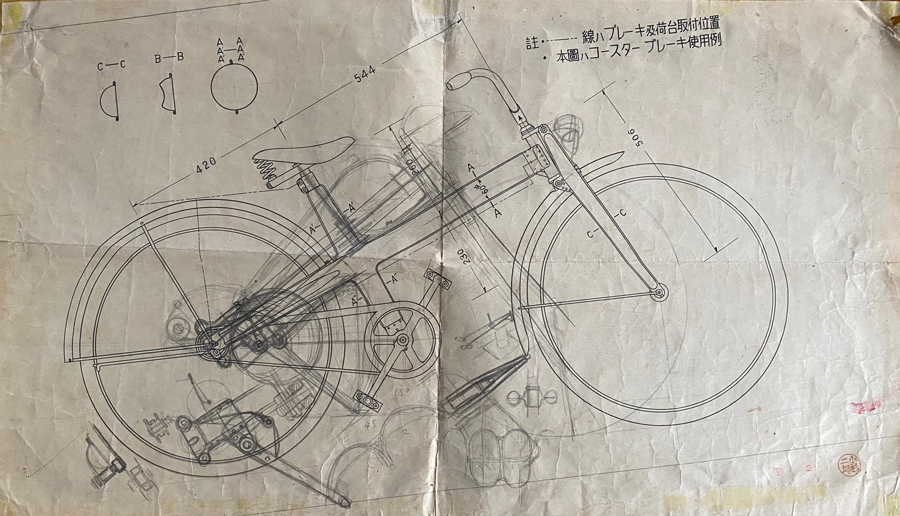

He was born in 1915 as the second child of the Western-style painter Kosugi Hoan (Kunitaro) and his mother Haru. He entered Tokyo Municipal First Junior High School (now Tokyo Metropolitan Kudan High School) and then the Design Department of the Crafts Division of the Tokyo Fine Arts School. Iwataro Koike, a senior student at the school, recalls that he was unique in the school's tendency towards decorative designs. His graduation project was a chair and table. After graduation, he entered military service and worked in the vehicle repair industry. He then worked for two years at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's crafts institute, where he completed a wooden pilot's seat for a bomber aircraft made of plywood that could withstand 9G, a feat that astonished the aviation industry. After leaving the institute, he obtained a patent for the construction of a bicycle and presented a design for a pressed cross-shaped frame bicycle. The number of patents and utility models he applied for in his lifetime is said to have reached 200.

At Toyo Kogyo, he advocated a ‘two-wheeled scooter-like coupe’ with the "R360 Coupe", created lovely forms and tried designs that captured people's hearts, such as painting inorganic trucks pink, but he rejected design for design's sake, believing that form should follow function. He said that original design could only be desired with the backing of original technology, and he focused on technological progress.

He was a founding member of the Japan Industrial Designers' Association (JIDA) and an advocate of organisational development, and when he was President of JIDA, he opposed the Ministry of International Trade and Industry's attempt to launch the Good Design Award, pointing out the lack of awareness of industrial design as being self-righteous, and urged members to decline the award. When he was President of JIDA, he opposed the Ministry of International Trade and Industry's attempt to launch the Good Design Awards, pointing to a lack of awareness of industrial design, but also that it could hinder the promotion of design, and had the members resolve to decline the judging. He also announced that the association would not participate in the World Design Conference in 1960 as it was premature, but stated that there were no restrictions on individual members' participation.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Toyo Kogyo (now Mazda)

"CT/1200" (auto tricycle) (1950); “Romper” (1958), “K360” (1959) ; “R360 Coupe” (1960); “B360” (1961) ; “B1500” (1961); “T2000” (1962); “Carol 360” (1962)

Janome Sewing Machine Industry (Janome Sewing Machine)

"Model 320" (1954); “Model 560” (1961); “Model 670” (1964); “Model 366” (1966); “Model 801” (1971); “Model 820” (1979); “Model 817” (1980)

New Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (now Mitsubishi Heavy Industries)

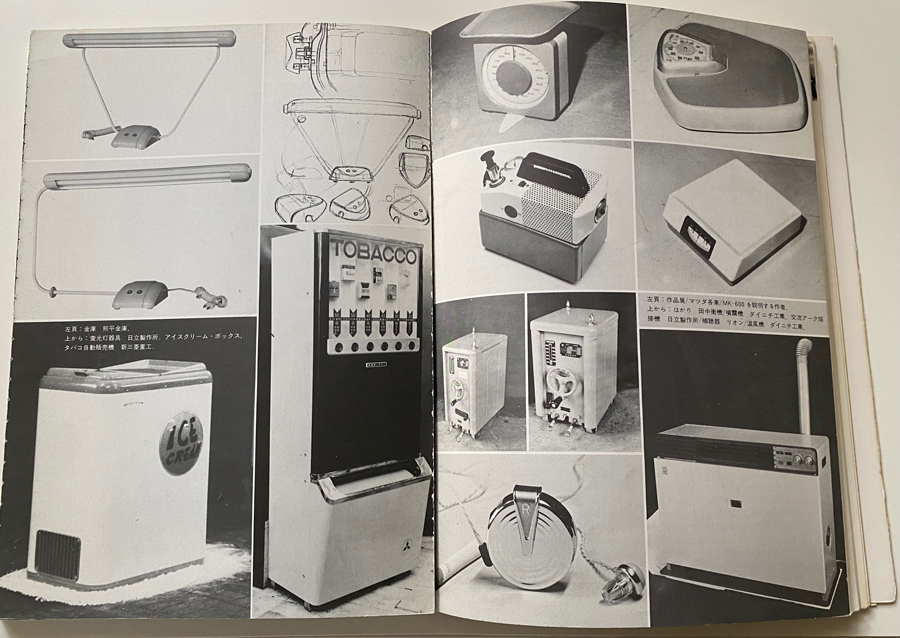

"Silver Vision C57" (1954); "Silver Vision Bobby Deluxe C-80" (1957); "Silver Vision C-110" (1959); "Silver Vision Bobby 300" (1959); "Silver Vision C111" (1960); "Silver Vision C135" (1963); ice-cream boxes, air-conditioner

Companies in Sanjo, Niigata Prefecture

Maruto Hasegawa Kosakujo KEIBA Nippers, wire strippers and many other hand tools; Dainichi Industry hot-air heaters, sprayers; Tanaka Scale Works scales, kitchen scales

Others

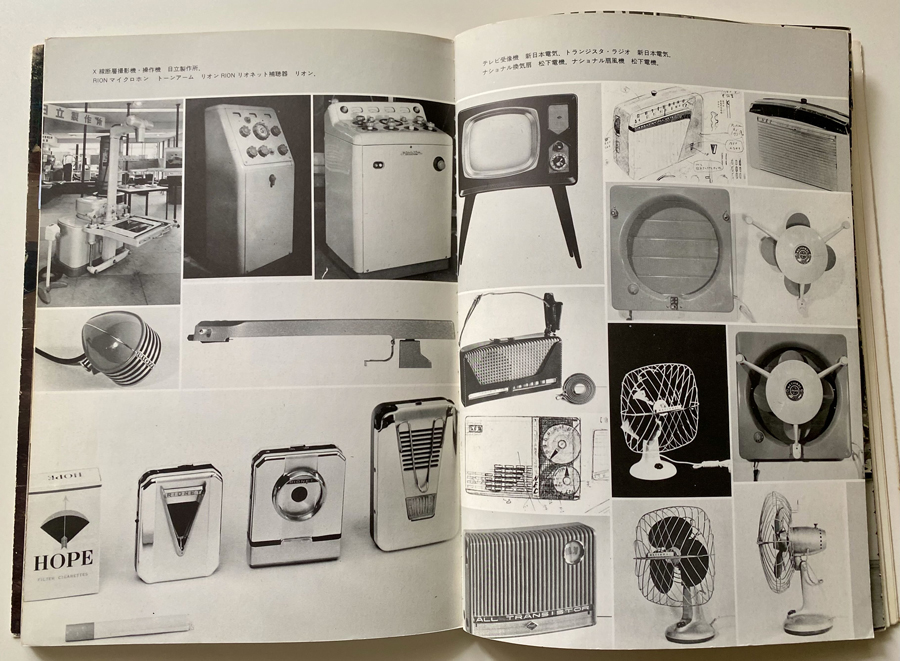

Asahi Beer PR car (1950); Hitachi X-Ray device; Kobayashi Riken Seisakusho (now Rion) hearing aid (1956); Shin Nippon Electric(NEC Home Electronics)TV; Matsushita Electric Industrial (now Panasonic) fan, ventilation fan; Kumahiira Manufacturing safe (1960); independently developed automobile ‘"MK-600" (1965)

Books

”My Industrial Design: The People and Works of Jiro Kosugi”, Maruzen (1983)

Interview 1

Interview 01: Shigeru Onawa

Location: O Design Collection

Interviewee: Shigeru Onawa, industrial designer

Interviewer: Tomoko Ishiguro

Auther: Tomoko Ishiguro

On the occasion of the interview

More than 40 years after his death, it is difficult to trace the whereabouts of personnel and archives of his activities in his day. Jiro Kosugi was a pioneer of Japanese industrial designers who created the Toyo Kogyo "R360 Coupe" and "Carol 360", and the sewing machines of the Janome Sewing Machine Industry, etc. In 1954, he held the first solo exhibition of industrial designers in Japan at the Bridgestone Building, and in 1965, he presented the "Jiro Kosugi Industrial Design Products Exhibition". Kosugi died suddenly in 1981, and although the exhibition "30 Years of Design and the Trajectory of Jiro Kosugi" was held at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music in 1984, there were no more opportunities to come into contact with his work after that. In 2015, the Tsubame-Sanjo Local Industry Promotion Centre held the "Tsubame-Sanjo Design DNA Yusaku Kamekura and Jiro Kosugi" exhibition. The curation and exhibition of the works was led by industrial designer Shigeru Onawa, who conducts archival research for JIDA. We decided to interview Onawa about his research into Jiro Kosugi and the state of his archive.

Shigeru Onawa : Born 1951. Graduated from Kuwasawa Design School. After working for an automobile parts manufacturer, a photographic lighting equipment manufacturer and an ID office, he became independent in 1977 and is a member of JIDA. Since 2000, he has been archiving his collection of actual products, lending them to design exhibitions and organising exhibitions.

No other product designer has probably delivered 16 cars in his lifetime.

Incredibly exquisite prototypes

ー Shigeru Onawa curated and managed the "Tsubame-Sanjo Design DNA Yusaku Kamekura and Jiro Kosugi" exhibition held at the Tsubame-Sanjo Local Industry Promotion Center in 2015. I would like to ask you about the impetus for the Jiro Kosugi exhibition and its archive.

Onawa In 2010, I taught industrial design at the Niigata Prefectural Sanjo Techno School for five years. Before taking up my post, I organised a JIDA Design Museum exhibition at the Tsubame-Sanjo Local Industry Promotion Center and found that there was a deep connection between that place and Mr Kosugi. After I was transferred to Sanjo, I became even more interested in the area and began a full-scale research and collection of his works and materials. During my five years at Sanjo Techno School, the school held two design forums on the results of this research and investigation, and I was able to introduce his work in Sanjo.

ー I understand that Mr Kosugi's former teacher at the Tokyo Fine Arts School, craftsman Matsugoro Hirokawa from Sanjo, connected Mr Kosugi with the town of Sanjo. As a commissioned designer, Mr Kosugi visited Sanjo about once every two months, working on 10-50 projects in two days and consulting on various local designs for about 30 years until the year of his death. He made great efforts to promote production in the local industry.

Onawa A hand tool manufacturer called Maruto Hasegawa Kosakujo (hereafter Maruto) has been providing design advice since 1952, the first year of the guidance project. Eventually, the company moved from consultation through the government to individual contracts. The first advice seems to have been on how to raise the company's profile as a manufacturer, and Mr Kosugi first suggested making an enamel signboard as a landmark and sending it around the country, designing and manufacturing it himself.

Enameled signboard designed by Kosugi for distribution to wholesalers across the country by the Maruto Hasegawa Kosakkujo.

Onawa According to the then managing director of Maruto, who knew him well, as soon as he received a design request, he would start drawing on the spot, and by the next time they met, he had already made a prototype and brought it to them. I was shown the prototypes, which were so elaborate that I was amazed at the degree of perfection. He repeated this process every time. It was so elaborate that we suspected it had been made by a specialist.

Mini nipper prototype (undated) that Kosugi reportedly brought with him.

ー Kosugi's work was supported by Fumio Matsumoto, who was a partner in the Mejiro office, and there is a section on Kosugi in Katsuhira Toyoguchi's book "From Kataji Kobo: Katsuhira Toyoguchi and the Half-Century of Design" (1987). According to the book, Mr Matsumoto worked with him for a few years, then they split up and he worked alone. In his later years, Mr Matsumoto also helped with the drawings and production of the "MK-600", a car that Mr Kosugi built himself out of FRP, but was he the one who built the prototype at Maruto? Are there any prototypes left at Maruto?

Jiro Kosugi explaining the "MK-600" sheet in his hand.

Onawa The person who corresponded with Mr Kosugi at that time had been retired, and I borrowed his prototype once to photograph it. When I saw the actual product, I could see that he must have really loved making things. It is really unbelievable that a designer could create such an elaborate product.

200 patents, utility models and design registrations filed

ー In Mr Toyoguchi's book mentioned earlier, it was written that he surprised the aeronautical engineers at the Industrial Arts and Crafts Testing Laboratory by creating a bomber cockpit that could withstand 9G. It could be said that Mr Kosugi went beyond the scope of a designer and played the role of an engineer and manufacturer. So he was well versed in mechanics and engineering.

Onawa I think so. He must have really enjoyed thinking up new mechanisms and actually working with his hands to make them. The office must have been equipped with machine tools and so on.

ー I think he learned more about machines and engineering from his own knowledge and skills than he did at university.

Onawa When he went to war, I don't know if he volunteered, but he was assigned to repair and adjust tanks. He must have been interested in anything to do with mechanics from an early age. One of the reasons for this was that when he left the army, he wanted to make his own bicycles and was working on becoming a manufacturer and selling them himself.

Pressed cross-framed bicycle and blueprints of the bicycle, published in 1947 in the "Industrial Arts News".

ー Tatsuzo Sasaki, who designed the "Subaru 360", became a freelance designer when Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, where he first joined, was broken up after the war. It could be said that, due to the circumstances of the time, it was possible to be involved in more projects as an external designer than as an in-house designer. Mr Kosugi may have felt the same way. He also insisted that "design is determined by one person's idea and is a one-off" and worked without a staff. It is said that he applied for up to 200 patents, utility models and design registrations in the course of his many jobs.

Onawa I was curious about the number of patents, so I looked them up, but there were not that many available online at the Patent Office. Designers sometimes register designs, but in Mr Kosugi's case, it seems that many of his design proposals involve structure and function, so I think he has more patents and utility models. Normally, engineers from manufacturers would apply for a patent, but in his mind, many of his design proposals included structure and mechanism, so it must have been a matter of course.

ー Mr Kosugi's works, their backgrounds and texts written by him are included in the book "My Industrial Design: The Person and Works of Jiro Kosugi", but there is nothing else that could be called an archive. Nor do museums and art galleries seem to collect products, with the exception of a few vehicles. You curated the exhibition "Tsubame-Sanjo, DNA of Design Yusaku Kamekura and Jiro Kosugi" in 2015, but it must have been difficult to collect the exhibits.

The book "My Industrial Design: The People and Works of Jiro Kosugi" lists a wide range of works, including hearing aids (Kobayashi Riken Seisakusho, from 1960, Rion Corporation), televisions (Matsushita Electric), fans (Matsushita Electric), fluorescent lamps (Hitachi), cigarette vending machines (New Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) and warm air blowers (Dainichi Industry). The listings include.

Onawa This exhibition was a two-person exhibition tracing the origins of design in Tsubame Sanjo, with one artist being Yusaku Kamekura, a native of Tsubame City (formerly Yoshida Town, Nishikanbara Ward), and the other being Mr Kosugi, who provided design guidance in Sanjo, both born in 1915 and held in 2015, 100 years after his birth.

Mr Kosugi's work was mainly collected by Sanjo companies. First, Maruto borrowed hand tool products such as pliers and wire strippers, as well as prototypes and NEC transistor radios from the personal collection of Haruo Hasegawa, who was the company's managing director at the time.

My collection includes Janome sewing machines, Rion hearing aids and National electric fans. It was difficult to display real Mazda cars, so I displayed a 1/43rd scale miniature car. The family members cooperated in various ways. His daughter Midori Yamamoto kept sketches and drawings which we were able to borrow, and his nephew Kojiro Kosugi, a Western-style painter, was a link to his eldest son Shigeru and also helped him with his work when he was in high school.

ー You have a private collection of various designs, don't you?

Onawa It's been about 30-40 years now, and my collection has grown to the point where I've rented a warehouse to store it. Some of the collections are also presented on Instagram with explanations.

ー It really is an archive.

Onawa I used to collect almost all of Mr Kosugi's sewing machines, but they were heavy and took up a lot of space, so now I only have two left and have given the rest away. were sold to M+ (Hong Kong Design Museum).

Industrial design is not just about appearance

ー In 1948, he was invited to become a commissioned designer at Toyo Kogyo (Mazda), which did not yet have an in-house designer. How did you come to be associated with Mazda?

Onawa According to the JIDA magazine "Industrial Design" (No. 57, 1957), a person told the vice-president of Toyo Kogyo that an industrial designer was designing cars in the US (presumably Raymond Loewy). The vice-president approached Mr Tokujiro Kaneko (who had design experience at Mitsubishi Motors), who was working with him at the time, to see if he could ask him to do the design, and he replied, "If you're going to do something like that, it's Kosugi", thus establishing Mr Kosugi's relationship with Mazda.

By the way, I went back through the records and counted how many cars he designed in his lifetime. Including Mazda cars and the independently developed "MK-600", he had designed 16 cars in his lifetime. That surprised me. I think there are not many Japanese designers who have worked on 16 cars. I also designed 27 sewing machines, which is quite a lot.

"Janome Type 817" (1980)

ー That is great. So there is a high probability that it will be commercialised?

Onawa I think most of them become products. In the case of the maruto mentioned earlier, the prototype was made to the same standard as the product and submitted to the manufacturer, so it was probably adopted as it was.

ー Kosugi wrote in Kogei News (1956, Vol. 24): Industrial design is based on industrial production technology, and the designer must have the same knowledge of production technology as the engineer, and the design must fully meet the requirements of overall mechanical performance. Designers must have the same knowledge of production technology as engineers and must ensure that the design fully meets the requirements of overall mechanical performance. Engineering and design, and the art of technical production, were combined in one person in order to increase the value of the product as a commodity. Perhaps it was the times, but once again he was a rare talent..

Onawa Considering the strength of Japan's industrial products at that time, it is true that products that were useful in many ways could not have been made without changes in this area. The argument is that it is not enough for designers to think only about the 'front', but that the final form is born from the 'inside', which is the basic foundation.

ー The idea that industrial design is connected to industry and society, so it is necessary to have an organisation as a group and to cooperate with companies and engineers, and he worked hard to establish and lead JIDA. However, he is opposed to the establishment of the G-Mark system, which could be seen as an aid to the promotion of design. What is your view, Mr Onawa?

Onawa When he was chairman of the board, I think it was daring at the time to speak out against what the government was trying to do in terms of promoting design. I think he felt a sense of crisis about the easy commercialisation of design. Industrial design should be more than just external design, it should fully satisfy production technology, production cost, usability and marketability, and if Good Design inadvertently selected something that did not satisfy these requirements, it could lead to a distrust of industrial design. I think he was worried that people would say: "Products with the Good Design mark on them are difficult to use".

ー This is not necessarily the case with the Good Design Award, but even today the phenomenon of 'good design but difficult to use' often occurs. He also said that if the Good Design Award is, as its name suggests, an incentive award for good design, we should carefully consider the seriousness of our responsibility.

Onawa I think it was a bold statement, because in 1965 he wrote in the JIDA magazine, "JIDA" he even wrote "Lately I have heard people say that the industrial designer's touch makes things worse. The voice that says it is cool but bad inside is an indictment of design on the part of the user, a brake on the progress of the machine, and possibly a fraud".

He liked to drink, and maybe he had something like this to complain about to his family when he was sober. The family have the archive, so I think it would be a good idea to interview them.

ー Yes, I would like to hear about it. By the way, Mr Onawa, you continue to do research for the archive at JIDA. How do you feel about archiving?

Onawa Every year since 1999, JIDA has conducted the JIDA Design Museum Selection, a project in which we select high-quality design products and donate them to companies and other organisations. In my work with JIDA, I focus on researching the history of products. I also have a deep-rooted collecting habit and love of things, so I research old designs from 1950 onwards and buy and collect what I can afford. When I look at these designs again and read old documents, I often discover that they are not what they seem, and I think that old books and documents are just as important as the things themselves.

I think that old books and documents are just as important as objects. When I went to talk to Yoko Uga earlier, she was going to throw away some old materials and photographs, so I was given them.

ー I think it's wonderful that you're collecting and researching these materials. What do you do with them?

Onawa I don't have many, but I lend them to museums and special exhibitions. I also give lectures at elementary schools, vocational schools and universities, showing them objects from the period and talking about design. Unfortunately, my children are not interested in this kind of collection, so I have to choose between finding someone or an organisation to pass it on to, or getting rid of it all. For the time being, I will continue to showcase the collection on Instagram and enjoy taking care of it.

By the way, there doesn't seem to be much corporate design in the PLAT archive at the moment, but there are people like Zenichi Mano from the former Matsushita Electric Industrial who made product design history from within the company. I hope that will be covered in the future.

ー Thank you very much for your comments. I would be happy to talk to Mr Onawa again about archival research methods and materials. Thank you very much.

Interview 2

Interview 02: Shigeru Kosugi, Akiko Kosugi

Location: Own residence of the interviewees

Interviewees: Shigeru Kosugi, Akiko

Interviewer: Tomoko Ishiguro

Auther: Tomoko Ishiguro

Jiro Kosugi lived for a long time in a quiet residential area in Suginami Ward, commuting to work in Mejiro. He worked tirelessly until shortly before his death. His eldest son Shigeru and Shigeru's wife Akiko, who lived with him until the end of his life, spoke about the state of the archives kept in his home and the unknown face of designer Jiro Kosugi.

We had good arrangements for everything.

I think that's why I was even able to suggest the ease of creation.

Design is not art

ー Today I am interviewing Jiro Kosugi's eldest son, Shigeru, and his wife, Akiko. Mr Jiro Kosugi was a master of engineering and sought functional beauty. I understand that his workplace was in Mejiro, separate from his home, and I would be interested to hear about his private life. Thank you for preparing the documents for the interview.

Shigeru Kosugi This is my father's starting point, or rather an early serpentine sewing machine that was commercialised after winning the"2nd Mainichi Industrial Design Competition". It was used at home.

Janome Sewing Machine Industry " Janome Model 320" (1954)

Akiko Kosugi I love it. The sewing machine cover is wonderful, isn't it? He designed it himself. We had lots of other things, like fans and stoves, but every time we moved, we gave them away and there were fewer and fewer of them. We wanted to keep them, but we just didn't have enough space...

ー Mr Jiro Kosugi is an essential figure in the history of industrial design, but only a limited number of industrial products remain in archives. In the case of Mr Kosugi, the largest archive is "My Industrial Design: The People and Works of Jiro Kosugi", compiled by Katsuhei Toyoguchi and others after his death. At the beginning of the book it says that the publication was made possible by the drawings, photographs and writings he left behind before his death.

Shigeru Yes, there are books that present individual items as products, but this is the only book that covers his work as an individual.

ー Shigeru, you are an engineer with a degree in mechanical engineering. How did you see your father's work?

Shigeru My father was in Mejiro in his later years, so I never saw him work in person, but he used to say, "That's not art" when it came to design. When my father worked, production technology was not as advanced as it is now, so he focused on ease of production as well as ease of use.

He liked the functional beauty of things like aeroplanes. People who design aeroplanes do not think about design. They get there by working out the function. Ships also have to deal with waves and water, and functional beauty is sought on top of that. They were not conscious of just looking good.

With the old Mazda trucks, my father made a lot of suggestions about the structure, and he designed them while discussing them with the engineers. He would even take into account the stamping dies for the product in his designs, and would not do anything that could not be done with the production technology of the time, which was not visible on the surface.

ー Did Mr Kosugi learn the basics of the technical aspects at the Ministry of Commerce and Industry's Crafts Institutes, and in addition, did he study on his own?

Shigeru I don't really know where he learnt about structural things, but since he was involved in making chairs for training aircraft during the war, he must have learnt on his own, in addition to studying at the design department at the University of the Arts. He also knew a lot about woodworking, and he knew a lot about pressing and other working techniques. He had been making gliders since he was young and was once stopped by his mother when he tried to fly one.

Akiko My grandfather-in-law (Hoan Kosugi (Kunitaro), a Western-style painter) wrote in his "Hoan Diary" that my father-in-law often took apart clocks and cameras when he was young, and that he thought the boy was good with his hands and might do useful work in the world in the future.

Shigeru I think he liked to think about mechanisms and systems. He wanted to make something that had all of that in it, rather than something that just had an outward appearance. Today, production technology is much more advanced and most of what designers want to do can be done. I feel that his way of thinking was different from that of modern designers.

Akiko For many years, my father-in-law was invited to and went to Tsubame-Sanjo, Niigata Prefecture, as a design consultant. When he went to Maruto Hasegawa Kosakujo in Sanjo, he would be asked for advice by people, and they would say that he would call them back on his way back to Tokyo from Sanjo after listening to their stories and giving them advice.

ー And I heard that he was going to take a prototype with him next time.

Shigeru Yes, he made something similar to the actual product by finishing it by hand, cutting acrylic sheets and so on. He could even make them myself.

ー Normally that would be outsourced, but he did it by hand in Mejiro.

Shigeru He had a lot of special tools. Starting with sewing machines, there were Mazda tricycles, trucks and minicars, as well as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries scooters, fans and even nail clippers. I think my father is the only person in Japan who has designed such a wide variety of products. Maybe it was a good time when he could design things on his own if he wanted to.

Modern cars are built in teams, so individual names don't appear. When I looked at Motor Fun magazine a long time ago, I was surprised to see Jiro Kosugi's name mentioned as a designer. Both trucks and small cars were designed by Jiro Kosugi. I think it was a really good time in that respect too.

ー Mr Onawa has counted that Mr Kosugi made 16 cars in his lifetime. I think that means that most of them were commercialised.

Shigeru But it seems that there were a lot of things he tried to make but couldn't. There were photos of models that never made it to market. So I don't think they were all commercialised.

Ability to manage projects

ー In 2019, he was honoured by the Japan Automotive Hall of Fame. In the introduction, he was described as a pioneer of "project management activities", where he would meet with people in different fields to complete a product. Mr Kosugi was active even before in-house designers were firmly established, and as an external designer he led in-house designers.

Shigeru Yes, but it might be different from just teaching. My father used to teach at the art department of Nihon University, but he wasn't good at teaching with words.

He didn't talk much at Mazda's internal presentations either. The way they did it was to ask people to look at it and judge it. For designers, the finished product is everything. They couldn't explain every single thing and sell it, so maybe that's why he didn't want to talk about it.

Akiko But since the designers weren't alone, maybe they could have organised the project without words.

Shigeru Still, I think his sense of colour and so on was unique at the time. I don't know how Mazda got permission to paint a light three-wheeled truck coral reef pink. It was an amazing use of colour at that time.

ー What was your father like at home?

Shigeru He went to the office in Mejiro almost without a day off. He only took the New Year's holiday on January 1st, but the rest of the time he was at the office. So I don't really remember playing with my father.

Whenever he thought of something, he would draw it on an advertising leaflet or a cigarette packet. I still have a lot of those hand-drawn sketches and notes. When he eats and has a smoke, he draws something a little bit. I think he was thinking not only about the design, but also about making improvements, applying for a utility model and so on.

Akiko You may not know this, but my father-in-law and mother-in-law were a close couple. They looked forward to having a drink in the evening when they came home. When he came home, we would all meet him at the door. Then my father-in-law and mother-in-law would have dinner and a glass of wine together. I loved this friendly atmosphere. It was wonderful.

ー Did Mr Kosugi apply for patents and utility models at the request of the manufacturer?

Shigeru I don't know. Of course, some of them were requested by them, but it seems that he also requested things that had nothing to do with that, things that just came to him. There are also a lot of things that he just put in but didn't get through. Including these, the number is 200.

For example, for a single radio, he came up with various innovations, such as the dial mechanism, the way the memory worked, the structure of the mechanism, etc., and filed them as utility models. There are many people who file patents, but it would be limited if they were designers. I think my father was special in that sense too.

NEC radios and leather covers.

ー From your point of view, what was your father's working style like?

Shigeru My father was good at planning everything. He would think about what materials to choose and how to make them, and he was very good at determining what the final result would be. Because he was able to do this on a regular basis, I think he was even able to suggest ease of production to the people who made the products. I thought that was amazing. And they do it beautifully. In contrast, I was often told: "What you do is dirty work" (laughs).

ー Maybe he was anticipating and simulating things in his head.

Shigeru That might have been part of it. Anyway, he would do it neatly up to the last detail.

If I remember correctly, he didn't work at night. I thought it was time to drink. He would get up around 10 in the morning, have a cup of coffee, go to the office, get ‘Morino Tanuki’, heaping soba and tanuki soba nearby for lunch, and be home by around 6:00.

ー Mr Kosugi didn't work through the night to meet deadlines or unreasonable demands from clients.

Shigeru He disliked excessive decoration, perhaps because his life revolved around regularity. He avoided the glittering chrome that was common on American cars at the time, preferring simplicity.

ー Did Kosugi interact with other designers?

Shigeru My father was close to people of his generation, like Sori Yanagi and Riki Watanabe. Iwataro Koike was a really good friend of him, and I remember that when my father died,Mr Koike flew over to our house and said: "It's still warm". My father called him 'Mr Gan'. I think he mostly hung out with people from the University of the Arts.

Plastic cars of the future

ー Now here is a preserved plaster model of his own"MK-600", which took him four years to develop into an FRP car, based on what he had seen and learnt at the Carrozzeria during a tour of Europe in 1961, mainly at the Turin Motor Show. Fumiro Matsumoto was involved in the design and her nephew Mr Kojiro Kosugi in the production. The engine and suspension came from Mazda, the chassis was redesigned using tube welding, the body was made of FRP and the seats and steering wheel were made of polyester, which was very advanced.

Plaster model of the "MK-600" left at home.

Shigeru When it was finished, there was an exhibition called the "Plastic Show" where it was displayed. It became the talk of the town and was featured on an NHK programme with Musei Tokugawa and Meiko Nakamura, and Meiko drove it, saying things like "This is a plastic car of the future".

My father did not have a driving licence and did not drive, so I donated the finished "MK-600" to the automobile club at Keio University, where my uncle taught. I don't think there are any left. When he made it, he was no longer attached to it. He didn't intend to keep it forever.

Akiko Even the ones we had, we gave away a lot. I know my father-in-law, so I still keep things like that, but I don't know if I'll be able to keep the materials until my children's generation, and then their grandchildren's generation.

Shigeru Products are thrown away when they break, and it is difficult to leave them behind. But after my father died, someone from the Janome Sewing Machine Research Institute brought us an album of all the sewing machines he had worked on. I was very moved. At the funeral when he passed away, the person in charge of designing air conditioners and scooters at Mitsubishi Heavy Industries also made an effort to visit us.

Album of works presented by Janome Sewing Machine.

ー This is another valuable resource. Will you continue to keep the archive at home?

Shigeru I have kept most of the photographs and other materials that appeared in the collection. The sketches he drew are also still there. He also did a lot of packaging design work at the request of people he knew. He also left some writings. He was even nominated for the pen club for a while and wrote essays of sorts. He was an industrial designer, but that term alone does not apply to him.

I'm not a designer, so I can't speak on a grand scale, but even in the car world, old cars are becoming more popular these days. I think there is something to be said for old things coming back to the fore. They were designed by them in that era, by trial and error. It's interesting to look at old things because we can feel it. It's also fun to wonder why they're dressed like that.

ー It's the message that the objects give. I felt once again that archives are necessary in that sense. Thank you for your time today.