Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Yoko Kuwasawa

Clothing Designer, Educator

Text: Mikiko Tsunemi (Design Historian・Former Professor of Kyoto Women’s University)

PROFILE

Profile

Yoko Kuwasawa

Clothing Designer, Educator

1910 Born in Kanda, Tokyo City

1928 Entered the Western Painting Department of the Teacher Training Course at Joshibi School of Art and Design (now Joshibi University of Art and Design)

1933 Entered the Shin Kenchiku Kogei Gakuin (New Architecture and Craft Institute)

Participated in editing the monthly magazine “Jutaku” (Housing)

1937 Joined Tokyosha, publisher of “Fujin-gaho” (Women's Pictorial) (until 1942)

1942 Established Kuwasawa Clothing Workshop

1947 Founded the ‘Clothing Culture Club’

1948 Participated in the founding of the Japan Designers Club (NDC)

Established the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Academy and assumed the position of Director

1950 Established the Kuwasawa Design (KD) Technical Study Group

Appointed Lecturer in the Fashion Department, Junior College Division, Joshibi University of Art and Design

1952 Lecturer in the Design Department, Faculty of Art, Joshibi University of Art and Design

Launched ”KD News”

1954 Founded Kuwasawa Design School

1955 Established Kuwasawa Design Studio Limited (until 1972)

1958 Received the 3rd Japan Fashion Editors' Club Award

1960 Professor, Department of Clothing, Joshibi University of Art and Design Junior College

1964 Participated in designing uniforms for personnel at the Tokyo Olympic Games

1966 Founded Tokyo Zokei University and assumed the position of President

1968 Designed the companion uniforms for the Folk Crafts Pavilion at the Osaka World Exposition (in collaboration with Yoshitaka Yanagi)

1973 Awarded the Medal with Blue Ribbon

1977 Passed away (12 April, aged 66)

Kuawasawa Gakuen Educational

Foundation Archive

Description

Description

Yoko Kuwasawa was, as her name suggests, the founder of what is now the Kuwasawa Design School and Tokyo Zokei University. Through her modern design education, incorporating Bauhaus principles, she laid the foundations for post-war design in Japan. Kuwasawa Design School in particular produced many outstanding talents who led Japanese design, including graphic designers Masuteru Aoba, Katsumi Asaba, and Keisuke Nagatomo; interior designers Shiro Kuramata, Shigeru Uchida, Hisae Igarashi, and Tokujin Yoshioka; as well as Itsuko Ueda, Taro Gomi, and Naoki Takizawa. What kind of person was Yoko Kuwasawa, who founded such a design education institution in an era when it was still difficult for women to work on the front lines, and who pursued design education according to her own convictions?

Born in 1910, Ms Kuwasawa graduated from Joshibi University of Art and Design before studying at the Shin Kenchiku Kogei Gakuin (New Architecture and Craft Institute), founded by architect Renshichiro Kawakita and attended by figures like Yusaku Kamekura. For Kuwasawa, absorbing the Bauhaus-derived education in composition here laid the foundation for her subsequent career as a clothing designer and educator, both grounded in the principles of modern design.

After the war, she worked primarily as a clothing designer. Her designs focused mainly on garments for everyday life, specifically workwear (including farm clothes and uniforms). Through the development of Vinylon, a synthetic fibre used in workwear, she explored the ‘beauty of the Japanese aesthetic’ alongside Yoshitaka Yanagi of the ‘Mingei movement’. Having studied Bauhaus principles, Kuwasawa, unusually for a clothing designer, employed solid knowledge, technical skills, and scientific investigation and analysis. Her approach resembled that of an industrial designer more than a clothing designer, yielding numerous outstanding achievements. This philosophy became a major motivation for establishing an educational institution.

Also noteworthy are the talented individuals who supported her. Alongside the aforementioned Yoshitaka Yanagi and Yusaku Kamekura, Tetsuro Hashimoto, Tadayoshi Sato, Setsu Asakura, Masaru Katsumi, Isamu Kenmochi, Kiyoshi Seike, Riki Watanabe, Masato Takahashi, Ikutaro Shimizu, Yasuhiro Ishimoto, and Itaru Kaneko practised new design education under Kuwasawa, functioning as a driving force within Japan's design movement of the 1950s. Here, we present a manuscript compiled by Mikiko Tsunemi, a design historian who researches Yoko Kuwasawa and authored “Yoko Kuwasawa and the Modern Design Movement”. It centres on Kuwasawa's role as a designer and educator within the context of post-war Japanese design.

Currently, Yoko Kuwasawa's materials and archives are organised as digital collections and archives at the Kuwasawa Design School, which she founded, and at Tokyo Zokei University.

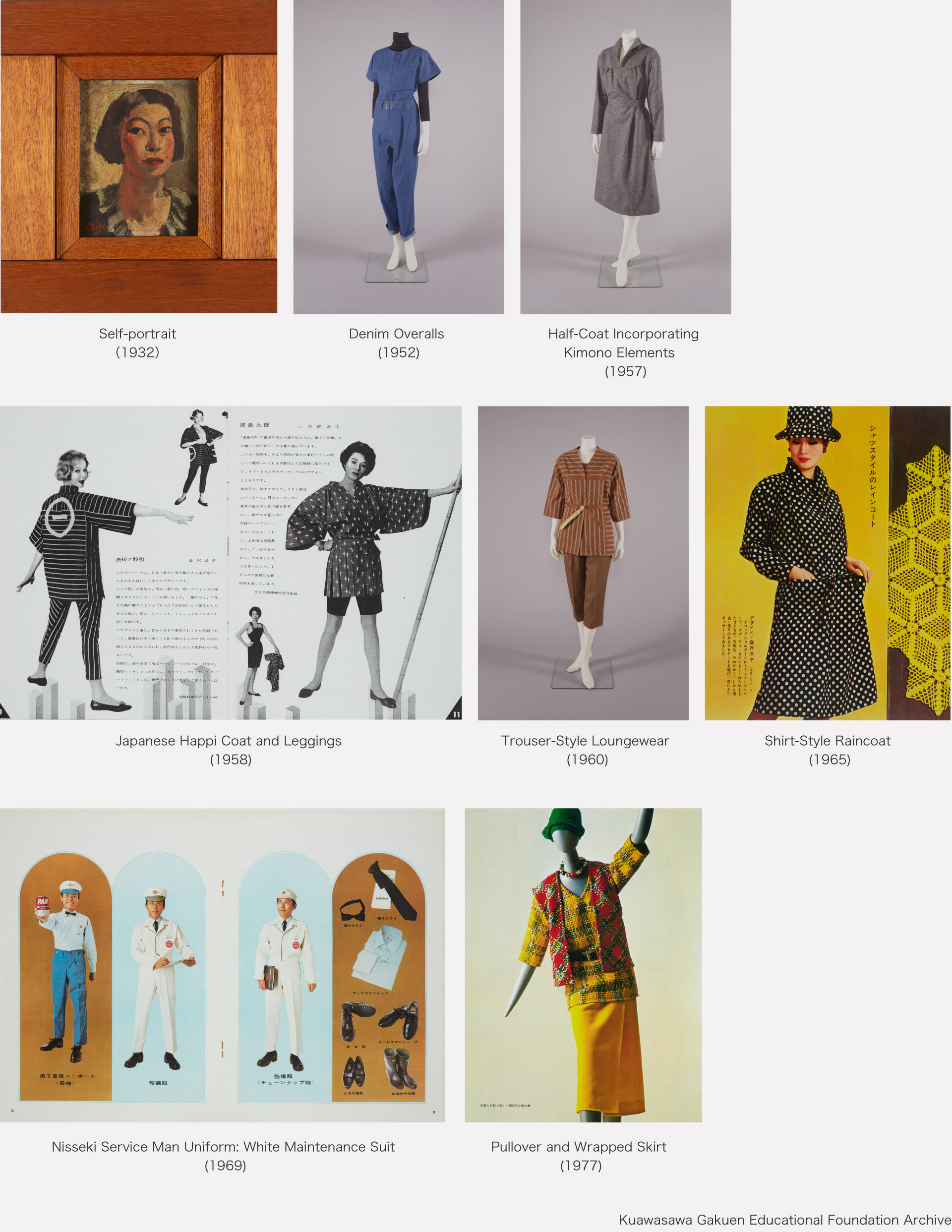

Masterpiece

Works

Denim Overalls (1952)

Clothes for Vinylon Exhibition Entry (1956) Textile: Yoshitaka Yanagi

Half-Coat Incorporating Kimono Elements (1957)

Japanese Happi Coat and Leggings (1958)

Trouser-Style Loungewear (1960)

Shirt-Style Raincoat (1965)

Nisseki Service Man Uniform: White Maintenance Suit (1969)

Publications

“Kimono”, Iwanami Shoten (1953), co-authored with Yasuro Ogawa

“Contemporary Accessories”, Kawade Shinsho (1956), co-authored

“Colours of Daily Life”, edited by Masaru Katsumi, Kawade Shobo (1956), *Chapters 6–10 authored by Kuwasawa

“Everyday Wear Designer”, Heibonsha (1957)

“People from the Prehistory of Japanese Design’ in A Brief History of Japanese Design”, edited by the A Brief History of Japanese Design Editorial Group(1970)

“Yoko Kuwasawa's Fashion Design”, Fujingaho Publishing (1977)

“Collected Essays and Posthumous Writings of Yoko Kuwasawa”, Kuwasawa Gakuen Educational Institution (1979)

“Good Design Is Not About Novelty, but About Being Useful

When Worn or Used in Daily Life”

The Roard to a Designer

Birth

Yoko Kuwasawa was born in 1910 as the fifth daughter of Kenzo and Shima Kuwasawa, who ran a silk fabric wholesaler, at 18 Higashi-Konyamachi, Kanda Ward, Tokyo City (present-day 2-2-6 Iwamotocho, Chiyoda Ward). Her mother Shima never yielded on matters she believed to be right, even when arguing with her hasband. She taught her children that women should live with integrity on equal terms to men, unconstrained by the conventional wisdom that women were inherently weaker. She chose clothing not for aristocratic display, but for its common sense, dignity, and practicality.

Studies at Joshibi School of Art and Design and the New Architecture and Craft Institute

In 1928, Kuwasawa enrolled in the Western Painting Department of the Teacher Training Course at Joshibi School of Art (now Joshibi University of Art and Design). Recalling her time at Joshibi, she stated: ‘Even when painting still lifes, I preferred thistles and wild lilies to beautiful apples or roses. When it came to figures, I wanted to paint men in indigo-dyed turtleneck sweaters rather than elegantly dressed women.’ However, despite advancing to the Western Painting Department, the new style of painting did not significantly stir her heart.

Six months after graduating from the Joshibi School of Fine Arts (renamed), in 1933, Kuwasawa enrolled at the New Architecture and Craft Institute(Shin Kenchiku Kogei Gakuin), a night school teaching the fundamentals of new architecture, commercial art, and painting. This school was founded by the architect Renshichiro Kawakita (1902-75). Lecturers included Takehiko Mizutani (1898–1969), who had studied at the Bauhaus in Dessau, and the couple Iwao (1898–1987) and Michiko Yamawaki (1910–2000). At the time, the academy, which incorporated the Bauhaus preparatory course curriculum, was the focus of considerable attention. It was at this academy that Kuwasawa first encountered the Bauhaus. Later in life, she recalled: ‘I would hurry along to this evening school after work. The academy's educational content centred on the pursuit of form aiming for architectural synthesis, with a focus on unique foundational training in form, termed “Education of Composition”.’

Education of Composition was a new teaching method that progressively built from ‘flat composition’ to ‘three-dimensional composition’, from ‘colour composition’to‘material composition’, and finally to ‘structure’. It was an education that fostered new art by freely employing the three formative elements of shape, colour, and material, using both eye and hand.

From January to July 1934, the academy comprised six departments: Composition Education, Western Dressmaking, Textiles, Architecture, Painting, and a Drama Course. During this period, as an experiment applying composition education to women, the Western Dressmaking and Textiles departments were held during the day.

Tetsuro Hashimoto, who taught at this academy, became a central figure in establishing the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Academy and the Kuwasawa Design School after the war. Furthermore, graphic designer Yusaku Kamekura was a year junior to her at this academy and subsequently collaborated with Kuwasawa on various projects.

Photographer Shigeru Tamura (former husband) and his Burma assignment brought together colleagues from the New Architecture and Crafts Institute and "Fujin-gaho" (1942) Kuawasawa Gakuen Educational Foundation Archive

As an editor

While attending the academy, Kuwasawa gradually became aware of modern design through assisting with the editing of the magazine “Architectural Crafts I SEE All”, presided over by Kawakita, and the co-authored work “Comprehensive System of Composition Design Education” by Kawakita and Takei Katsuo. She later became a reporter for the architectural magazine “Jutaku” (Housing), and through interviewing architects active in the 1930s, she also embraced modernist thought. After editing the New Year supplement “New Styles of Living” for “Fujin-gaho” in 1937, she joined Tokyosha (now Hearst Fujin-gaho-sha) as a fashion editor for the magazine. However, dissatisfied with the work, she left Tokyosha in 1941.

This formative period held profound significance for Kuwasawa. Crucially, through her work as a reporter for Jūjō and Fujin Gahō, she established a network connecting architects, photographers, folk craft practitioners, and contemporary studies scholars from the 1930s onwards. This network would play an exceptionally vital role in Kuwasawa's post-war endeavours as a designer and design educator.

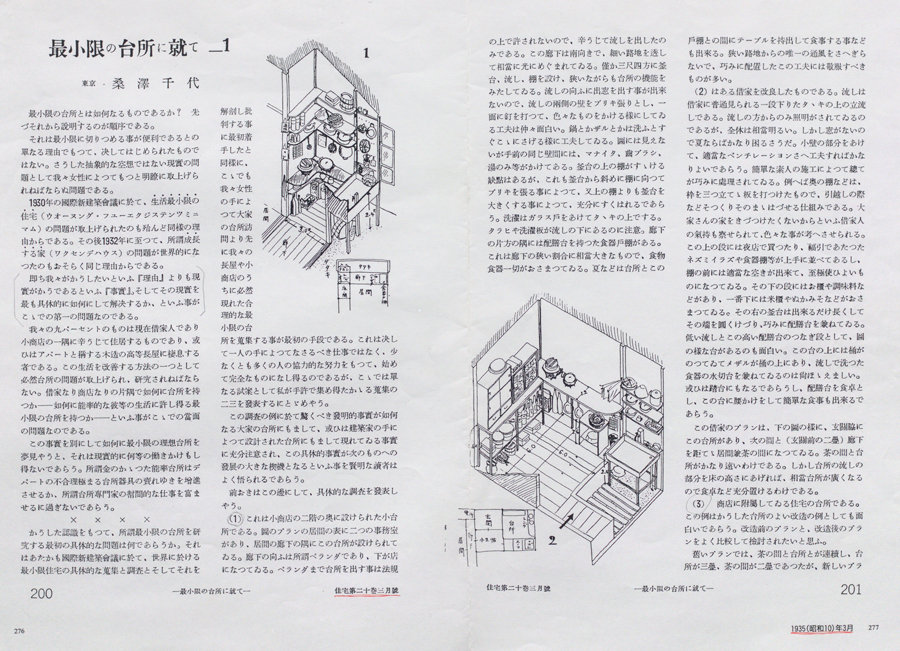

From articles Kuwasawa handled during her time as an editor. Illustration for a minimal kitchen survey (1935)

Kuawasawa Gakuen Educational Foundation Archive

As a Clothing Designer

Designing workwear and field clothing

After becoming freelance, Kuwasawa established the ‘Kuwasawa Clothing Workshop’ in Ginza in 1942, commencing her career as a fashion designer. She presented collections such as ‘Basic attire for young people, assembled from recycled materials’. Concurrently, she endorsed the ‘Women's Democratic Club’ (founded 1946) established post-war by Setsuko Hani and Shizue Kato. From her perspective as a dressmaker, she undertook educational activities for women, lecturing across regional cities and farming/fishing villages. She also co-founded the ‘Clothing Culture Club’ (1947) with stage costume designer Umeko Hijikata, becoming a leading figure within it.

Furthermore, through events such as conferences organised by “Fujin Asahi”, she expanded her wide-ranging activities. These included the ‘National Workwear Competition’ and educational efforts to improve women's social status and support their economic independence through the improvement of workwear and farm clothing.

Uniform Design

Kuwasawa designed numerous workwear items requiring functionality (including uniforms and field clothing). She reportedly designed around 50 uniform designs in particular.

As design surveys (including competitor research, operational analysis, and design development) were essential for workwear design, she actively incorporated industrial design methodologies. A prime example is the ‘Nippon Oil Service Man Uniform’. She conducted operational analysis at petrol stations and established the previously non-existent ‘maintenance uniform’. The white overalls-style maintenance uniform, revised in 1972, was worn for an extended period of 17 years (1972-1989). It became one of Kuwasawa's signature works and served as the prototype for maintenance uniforms.

Centre: 1960 Tokyo Olympic Games uniform. Exhibition: ‘Yoko Kuwasawa: Designer Who Created the Ordinary – Trajectory of Activity and Education’ Commemorating the 60th Anniversary of Kuwasawa Academy Educational Foundation and the 40th Anniversary of Yoko Kuwasawa's Passing. Organised by: Kuwasawa Gakuen Educational Foundation (2018)

Kuawasawa Gakuen Educational Foundation Archive

The Development of Vinylon Synthetic Fibre and the Mingei Movement

During the 1950s, vinylon was the most widely used material for workwear. It was the only synthetic fibre that could be produced using Japan's own technology and domestic materials. Through the development of vinylon, Kuwasawa interacted with Soichiro Ohara of president of KURABO INDUSTRIES LTD. and Yoshitaka Yanagi of the Mingei movement. She learned the Mingei spirit of ‘the beauty of utility’ and adopted the beauty of ‘everyday wear’ in fashion as her own design philosophy. Ohara held Kuwasawa in high regard, stating, ‘Ms Kuwasawa is a designer with a solid philosophy of form, working as an industrial designer.’ Her signature work, the ‘Nippon Oil Service Man Uniform,’ can truly be considered a prime example of ‘industrial design in fashion.’

Ready-made Clothes design

Kuwasawa focused on ready-made clothes rather than order-made garments from an early stage, designing with mass production in mind. In 1954, coinciding with the opening of DaimaruTokyo, she established the ‘Kuwasawa Easy Wear Corner’ and ‘Kuwasawa Originals’. This corner sold garments designed by her based on her concept of ‘coordinating through units’, which proved highly popular and sold very well. The ready-made clothes she aimed to create were ‘standardised’ clothing, representing modern design that sought equality through the object itself, distinct from individualisation. Thus, she proposed ‘coordination by unit’ – essentially, the combination of individual pieces – as a method to personalise these standardised ready-to-wear garments.

Establishment of the Kuwasawa Design Studio

Kuwasawa Design Studio (1955–1972) underpinned Kuwasawa's design practice. This studio supported both Kuwasawa's design work and her design education activities, while also liaising directly with industry to develop design proposals and produce samples. It further served an internship-like function, nurturing graduates of the Kuwasawa Design School.

Design Practice and Education

Founding of the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Institute

From the early post-war period, Kuwasawa dreamt of establishing a research institute capable of providing design education grounded in the ‘composition’ principles she had studied at the New Architecture and Crafts Institute.

Through his enlightenment activities, she became acutely aware of the necessity for proper fashion education for professionals. She thus conceived the ideal of establishing a school teaching such professional skills – a ‘vocational school’ – specifically a comprehensive ‘Clothes Design School’ thoroughly incorporating design studies and fashion design. This demonstrates that she had long hoped to establish a design school grounded in a broader concept of design—design studies and costume design—rather than fashion education confined to the narrow meaning of “sewing and dressmaking techniques”.

Kuwasawa founded Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Institute in 1948. Sculptor Tadayoshi Sato taught figure drawing there at her request, while painter Setsu Asakura (1922–2014) taught costume drawing and fashion sketching.

Then, in 1954, she established the Kuwasawa Design School, aiming for modern design education, and set up the Dressmaking Department and the Living Design Department (initially evening classes only for the first year).

At its founding, lecturers included Tetsuro Hashimoto (colour), Tadayoshi Sato (drawing), Setsu Asakura (costume drawing), and Akira Ishiyama (fashion design) from the Tamagawa Fashion Design Institute era, alongside Masaru Katsumi (design theory), Isamu Kenmochi (design theory), Itaru Kaneko (household goods), Kiyoshi Seike (living spaces), Riki Watanabe (household goods), Masato Takahashi (composition), and Ikutaro Shimizu (Sociology). This stemmed from Kuwasawa's philosophy that design is intrinsically linked to ‘society’.

The early Dressmaking Department was taught primarily by graduates of the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Institute, members of the KD Technical Research Association, and committee members of the Clothing Culture Club, centred around her.

Meanwhile, in the Living Design Department, critic Masaru Katsumi (1909–1983), introduced by Tetsuro Hashimoto, taught ‘Design Theory’ and played a central role in selecting lecturers and determining the curriculum. At that time, Katsumi was promoting initiatives such as the Good Design Movement. He later became a professor at Tokyo Zokei University, serving as Head of the Design Department. Furthermore, owing to his connection with the Ministry of International Trade and Industry's Craft Guidance Centre, he made significant contributions, including inviting Isamu Kenmochi and Itaru Kaneko, who worked at that centre, to serve as lecturers. Subsequently, Katsuhei Toyoguchi(industrial design), Yasuhiro Ishimoto and Masagiku Takayama (compositional education), and Hiroshi Hara, Yusaku Kamekura, Takashi Kono, and Ryuichi Yamashiro(graphic design) also joined.

The lecturers from the Dress Department and the Living Design Department shared progressive ideas, actively engaging with individuals from different design fields across departments to cultivate a creative atmosphere within the institute.

Kuwasawa articulated the essence of good design: ‘Good design is not merely novel; it must be something that, when worn or used, genuinely serves the wearer or user in their daily life.’

In June 1954, Walter Gropius, the first director of the Bauhaus, who had come to Japan for the ‘Gropius and the Bauhaus’ exhibition, visited the Institute accompanied by Isamu Kenmochi. Thereafter, the School to be introduced as the ‘Japanese version of the Bauhaus’.

Gropius (second from right) visiting Kuwasawa Design School. Yoko Kuwasawa (second from left) welcoming him.

Kuawasawa Gakuen Educational Foundation Archive

Composition as the fundamentals of design

The early teaching of ‘composition’ as the fundamentals of design was pioneered by Masato Takahashi and photographer Yasuhiro Ishimoto. 'Composition' was offered in all classes, though the educational content differed between them. This class-specific composition curriculum followed a hierarchical structure: starting with foundational content aimed at fostering free creation and expression, progressing to composition exercises on a flat plane, then training in form and spatial awareness, and finally culminating in comprehensive exercises considering the three design elements of form, colour, and material alongside structure.

Tokyo Zokei University: Its Background and Practice

In the commemorative publication marking the 10th anniversary of the Kuwasawa Design school, Kuwasawa wrote: "To further enrich and develop the achievements of the past decade and bring us one step closer to our ideal, the concept of establishing a university emerged as a 10th-anniversary project for the Kuwasawa Gakuen Educational Foundation and Kuwasawa Design School.The following year, 1965, saw the commencement of preparations for establishing the university, beginning with the purchase of the campus site. In 1966, Tokyo Zokei University was founded and is today positioned as one of the ‘Tokyo Five Art Universities’.

Kuwasawa's Design Philosophy

Modern Design Principles: Functionalism, Rationalism, Mass Production

Through her work as an editor, designer, educator, and advocate, Kuwasawa distilled the principles of modern design: functionalism, rationalism, and machine-based mass production.

'Functionalism' is a design theory prioritising function above all else, frequently invoked in discussions of Modernism, aiming to unify aesthetic and practical value. Clothing demanding the highest functionality is workwear (including field garments and uniforms). As a functionalist, Kuwasawa centred her design practice on workwear.

In clothing, the functional element lies in ‘easy of wear’, born from the exploration of ‘the relationship between human movement and wearable prototypes. Recognising that ‘the human body is a complex, moving three-dimensional entity, and clothing envelops the moving human’, the ‘Kuwasawa’s Prototype’ was developed. This prototype underwent twelve revisions until her death in 1977.

Kuwasawa also distilled her rationalist approach – selecting and utilising elements most efficiently to achieve a specific purpose – into the concept of the ‘wardrobe’. Specifically, she proposed a wardrobe centred around basic designs, featuring separates made from the same fabric that could be combined in various ways, thus enabling diverse styling options.

In fashion, ‘mass production’ refers to ready-to-wear garments produced in large quantities by sewing machines. Kuwasawa explained her rationale for pursuing ready-to-wear: 'For Japanese women's attire to become more beautiful, is it not essential to create fine products for them to wear? To achieve this, I believed ready-made clothing, rather than bespoke, was required.' From 1954, she established a ready-to-wear shop called ‘Kuwasawa Originals’ at Daimaru Tokyo Store, selling casual wear. She believed that producing ready-to-wear would lower prices, advance ‘equality through goods’, enable women designing ready-to-wear to become self-sufficient as skilled professionals, and contribute to women's liberation.

Good Design

In her essay ‘Fashion that Lives in Daily Life’, she defined ‘Good Design’ in fashion as follows: "It is knitwear for everyday wear that does not constrain the body; it is the pantaloons and jeans look; it is pullover sweaters and T-shirts – essentials indispensable to everyone. (Omitted) The design of daily necessities should embody the new sensibilities demanded by the times, feature comfortable patterns using good materials, offer a wide range of sizes, and be affordable. Such products are life fashion and good design.‘ She prioritised ’clothing that lives within daily life" in her design approach.

‘Japanese Element’ in Fashion

Modern Japanese design was created with an emphasis on Japanese originality. Kuwasawa, in particular, spent her entire life exploring the ‘Japanese element in fashion’, seeking to create new Japanese garments that would replace the kimono, distinct from imitations of the West.

She exhibited a ‘Happi coat and Hakama trousers’ at the International Cotton Fashion Parade held in Venice, Italy (1956). This was an outstanding piece demonstrating ‘Japanese taste’, evoking the firefighter uniforms of the Edo period.

‘Beauty of utility’ in Folk Crafts

After the war, Kuwasawa maintained close ties with figures from the folk craft movement such as Soichiro Ohara and Yoshitaka Yanagi. The synthetic fibre “Vinylon”, produced by Kurashiki Rayon where Ohara served as president, gained attention as a material for workwear. Yoshitaka Yanagi (nephew of Yanagi Muneyoshi), a textile artist, had participated in its development. In 1956, the “Vinylon Exhibition” (held from 24th to 29th February 1956 on the third floor of Daimaru Tokyo) was organised by Kurashiki Rayon. Kuwasawa handled the design while Yanagi oversaw the textiles. Recognising the importance of the folk crafts movement's principle of ‘ beauty of utility’, they began using the term “everyday wear”. Her populist sensibility, where ‘everyday’ equated to ‘daily life’, can be said to have run deep within the folk crafts movement's ‘beauty of utility’.

The Fusion of Modern Design and Folk Crafts

Kuwasawa placed great emphasis on the philosophy of modern design, yet was profoundly influenced by the spirit of folk crafts. Originally, modern design and folk crafts were fundamentally different, considering their production methods: machine versus handmade. Moreover, their finished products differed visually. However, the concept of ‘design for the masses’ inherent in modern design resonates with the spirit of folk crafts. Mingei taught modern designers about ‘unadorned functionality’. Kuwasawa shared this philosophy, incorporating the Mingei ideal of unadorned, functional beauty into fashion design, and dedicated himself to ready-to-wear garments mass-produced by sewing machine.

Workwear functionality varies according to the nature of the work. Therefore, the design process involves researching and analysing the work content before selecting the optimal fabric and creating patterns that account for bodily movement. On the other hand, as workwear serves daily labour, it must be unpretentious, ordinary, and of solid quality. In other words, the workwear to which Kuwasawa devoted his passion required both the functional beauty of modern design and the ordinary beauty of folk art. It can be said that through designing workwear, she achieved the fusion of modern design and folk crafts.

Design for Daily Life

At a time when innovative fashions were flooding in from America and Paris, the fundamental workwear and farm clothes of daily life were being neglected. Kuwasawa disliked clothes that were neither traditional nor practical, resembling costumes for fashion shows and merely seeking to be eccentric. Post-war, she was profoundly influenced by the “life”-centred philosophy of ‘Kogen-Gaku’ (contemporary studies scholars) Wajiro Kon (1888-1973), with whom she collaborated on improving Japanese farmwear for the magazine “Ie no Hikari”. Considering that Kuwasawa's educational and design activities concerning clothing were undertaken as part of life improvement, it is clear that Kon and Kuwasawa shared an extremely similar perspective on the concept of ‘life’.

People around Kuwasawa

Through his diverse activities before and after the war, Kuwasawa encountered designers, folk crafts practitioners, and Kogen-Gaku(contemporary studies scholars). As mentioned earlier, let us introduce several of them.

Tetsuro Hashimoto taught Kuwasawa as a lecturer at the New Architecture and Crafts Institute. After the war, he was deeply involved in founding the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Institute and the Kuwasawa Design Shcool. At the School, he taught colour theory and its applications as a lecturer. Yusaku Kamekura was a year junior to Kuwasawa at the New Architecture and Crafts Institute. They were friends who collaborated on various activities, and after the founding of the Kuwasawa Design School, Kamekura served as a lecturer there. Taro Takamatsu began working with Kuwasawa upon joining Fujin-gaho Co., Ltd. (Editorial Department) in 1946. He continued to support Kuwasawa's diverse activities from behind the scenes until her passing. Tadayoshi Sato taught at the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Institute and the Kuwasawa Design School, becoming a professor upon the founding of Tokyo Zokei University. Others, including Setsu Asakura, Konda Misa, and Masagiku Takayama, served as the third director. Itsuko Ueda, who served as designer to Her Majesty Empress Michiko for many years, and others supported the institute's educational activities after Kuwasawa's death.

Thus, surrounding Kuwasawa were not only networks dating back to the pre-war period, but also the lecturers who taught at the Tamagawa Western Dressmaking Institute, the Kuwasawa Design School, and Tokyo Zokei University – that is, the designer network that spearheaded Japan's design movement from the 1950s onwards – along with individuals who personally supported Kuwasawa. It was this broad network of connections and support that continually underpinned her design practice, her design advocacy work, and her design education. In the immediate post-war period, when the profession of designer was not yet established and it was difficult for women to play an active role in society, it is no exaggeration to say that Kuwasawa's achievements were nothing short of miraculous.

Location of Yoko Kuwasawa's Archive

Kuwasawa Gakuen Digital Collection of Held Materials

https://www.kuwasawa.ac.jp/collection.html

Tokyo Zokei University, ‘About Yoko Kuwasawa, Founder of Tokyo Zokei University’

https://www.zokei.ac.jp/university/founder/