Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Kaoru Mende

Lighting Designer

Interview: 20 June 2024, 10:30-12:00

Place of interview: Lighting Planners Associates (LPA)

Interviewee: Kaoru Mende

Interview: Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Kaoru Mende

Lighting designer

1950 Born in Tokyo

1977 Completed Master's degree in Tokyo University of the Arts

1978 Joined LD Yamagiwa Laboratory

1980 Moved to TL Yamagiwa Laboratory

1990 Established Lighting Planners Associates Ltd.

Founded Lighting Detectives

1997 Awarded the Mainichi Design Award

2002 Professor at Musashino Art University, Department of Scenography,

Display and Fashion Design (-2013) / Visiting Professor (2013-Current)

Description

Description

Kaoru Mende is a pioneer in creating the new design field of ‘lighting design’. The footprints of him and Lighting Planners Associates (LPA), which he founded, are directly related to the history of architectural and urban lighting in Japan. In the late 1970s, when Mende joined Yamagiwa and set his sights on becoming a lighting designer, Japan was undergoing a major change in the way modern architecture, which until then had embodied functionality and rationality, was being constructed. Leading this change were architects Arata Isozaki and Toyo Ito, with whom Mende collaborated on many projects. The two realised the importance of ‘light’ in architecture' and were looking for a partner to accompany them in the field of lighting design. Kaoru Mende who had been active at TL Yamagiwa, appeared on the scene. In his book, he describes Isozaki as ‘a man whose relentless design philosophy of eliminating the presence of lighting fixtures in the architectural space, and of making the architecture itself a giant lighting fixture, made us tremble with excitement’, and Ito as ‘an architect who constantly demanded renewal of light to bring new air into architecture, with an ambition and sensitivity befitting an architect of light’, 'He is an architect who continues to innovate the equation of architectural lighting design with an ambition and sensitivity befitting an architect of light’. As Mende and LPA have steadily built up a track record through numerous projects, the concept of ‘lighting designer = luminaire designer = product designer’ has expanded to ‘lighting designer = light environment designer’.

In the 1990s, Mende expanded his activities overseas, particularly to East Asia, including Singapore. This was paralleled by an expansion from architectural lighting to urban and environmental lighting. Nowadays, light design has become a natural part of architecture and urban design. We stroll through beautiful nightscapes, enjoy lighting up and watch projection mapping. At the same time, however, harmful and excessive lighting has also appeared and discussions about ‘light pollution’ have started to take place. He has been researching the current state of lighting design and raising issues through the ‘Lighting Detectives’, which was launched at the same time as the LPA. Here, we interviewed Kaoru Mende, who is always looking ahead to the next stage in lighting design, about his work and design archive.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

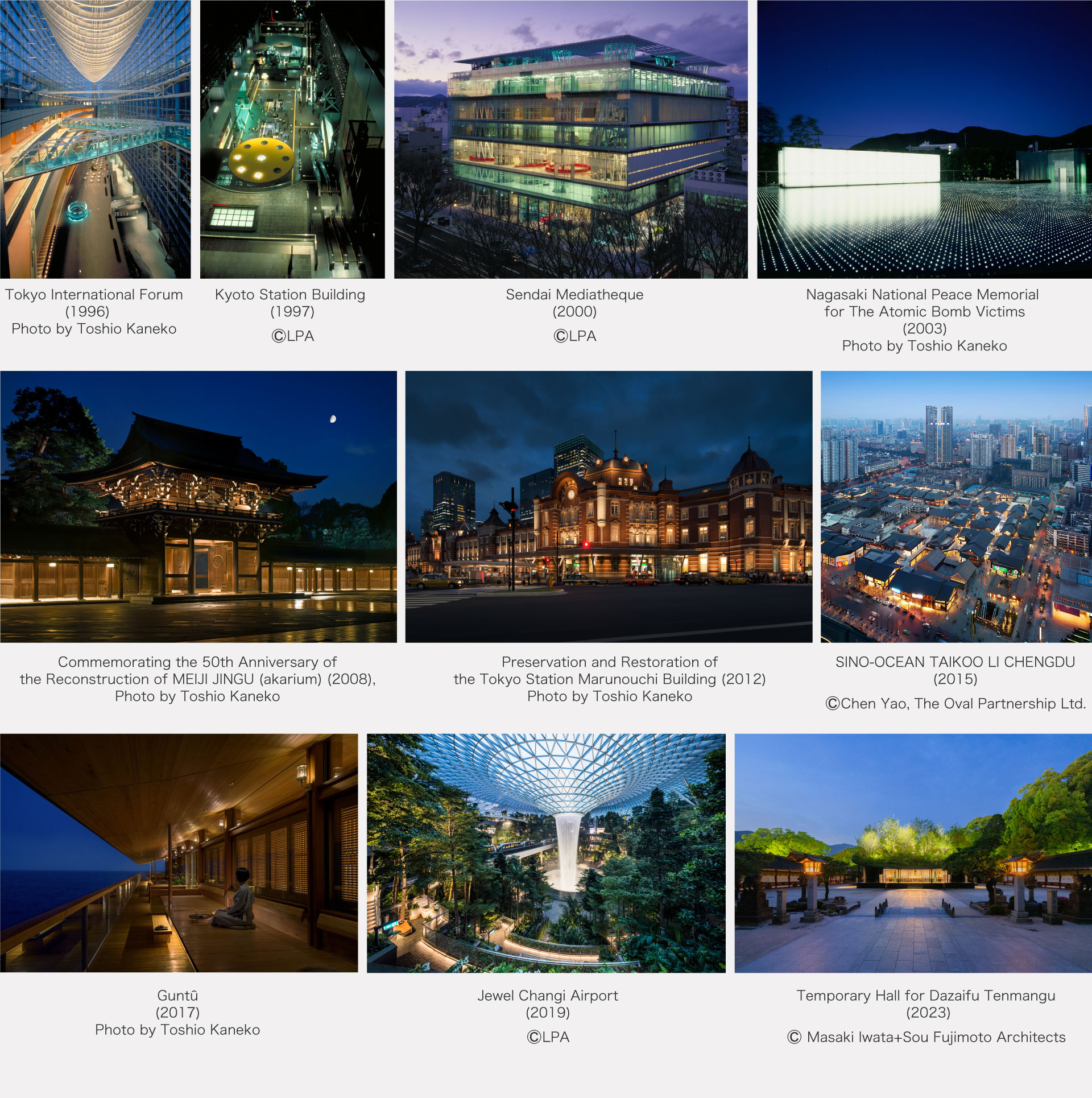

Tokyo International Forum (1996) Design : Raphael Viñoly Architects

Kyoto Station Building (1997) Design : Hiroshi Hara + Atelier Φ

Sendai Mediatheque (2000) Design: Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects

Nagasaki National Peace Memorial for The Atomic Bomb Victims (2003)

Design: Kyusyu Regional Development Bureau, A. Kuryu Architect & Associates

Roppongi Hills (2003) Design: KPF, The Jerde Partnership and others

Kyoto State Guest House (2005) Design : Nikken Sekkei Ltd.

National Museum of Singapore (2006) Design: W Architects Pte Ltd, CPG Consultants Pte Ltd

Lighting Masterplan for Shingapore City Centre (2006)

Integrated Consulting: Urban Redevelopment Authority of Singapore (URA)

Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Reconstruction of MEIJI JINGU (Akarium) (2008) Client: Commemorating the 50th Anniversary of the Restoration of Meiji Jingu

Preservation and Restoration of the Tokyo Station Marunouchi Building (2012) Design: JR East Tokyo Electric Works, JR East Architects and others

Gardens by the Bay, Bay South (2012) Design: Grant Association, CPG Consultants Pte.Ltd.

National Gallery of Singapore (2015) Design: Studio Milou Singapore, Pte Ltd.

Minna no Mori: Gifu Media Cosmos (2015) Design: Toyo Ito & Associates, Architects

SINO-OCEAN TAIKOO LI CHENGDU (2015) Design: The Oval Partnership/MAKE Architects

Guntû (2017) Design: Tsuneishi Shipbuilding, Yasutsugu Horibe Architects &Associates

Jewel Changi Airport (2019) Design: Safdie Architects

Takanawa Gateway Station (2020) Design: JR East Tokyo Construction Office, Kengo Kuma & Associates and others

Ishikawa Prefectural Library (2022) Design: Environment Design Institute / mindscape / TOTAL MEDIA

Temporary Hall for Dazaifu Tenmangu (2023) Design: Sou Fujimoto Architects

Main books

“Kaoru Mende + LPA: A Manner in Architectural Lighting Design” TOTO Publishing (1999)

“ Shomei Tanteidan (Transnational Lighting Detectives)”, Kajima Publishing (2004)

“Lighting Design for Urban Environment and Architecture” Rikuyosha (2005)

“Lighting Design: Designing with Shadow Design” Rikuyosha (2010)

“The Light Seminar” Kajima Publishing (2013)

“Manners in Architectural Lighting Design” TOTO Publishing (2015)

“LPA 1990-2015 Tide of Architectural Lighting Design” Rikuyosha (2015)

Interview

Interview

Great architecture always has great light.

The path to becoming a lighting designer.

ー You have realised many projects as a pioneer in architectural and urban lighting design. First of all, we would like to ask why you chose the field of lighting design.

Mende I majoured in design in the crafts department, and the first two years were a foundation course, and from the third year we could choose between visual or product studies, and I chose product studies. However, I had an oblique view of design, thinking that Japanese society had already experienced rapid economic growth and was already overflowing with things, so why should I make products now? So in postgraduate school I studied under Professor Toshiro Inatsugu, an architectural professor who was researching ‘Minka (Japanese private houses)’, and I became interested in environmental design.

ー After you graduated, you joined Yamagiwa, didn't you?

Mende Environmental design was not a profession at the time. So, I worked for Nikken Sekkei for a year and a half before joining Yamagiwa. There, I joined the team of the respected Shoji Hayashi and made models of various buildings. I received blueprints and made models, but when I actually made the models, I found that some parts didn't match up with the drawings, so I changed the designs to cope. After a while, I was asked to design architectural hardware such as door knobs and handles because I studied product design at the University of the Arts. When I was at university, I kept my distance from designing shapes, but when it came to work, I couldn't just run away, and there were no 3D printers , so I designed while struggling with plaster casts and moulds.

ー Why did you move from Nikken to Yamagiwa?

Mende I enjoyed my work, but I had a feeling that it would not be good if I stayed at Nikken. At that time, my former teacher, Iwataro Koike, who was also the founder of GK Design, introduced me to Yamagiwa President Hyogo Konagaya, who was a close friend of him. Mr Koike was also my matchmaker when I got married as a student.

ー You first encountered lighting design when you started working for Yamagiwa.

Mende At the time, Yamagiwa had established LD Yamagiwa Laboratory (hereafter LD) in 1970 and Yamagiwa Kosakusho (now TEC) in 1972 to strengthen the design and technical aspects of lighting fixtures, but the companies were not yet fully active. At that time, Mr Koike, who had been consulted by President Konagaya, approached me and I joined LD. LD was first headed by Takamichi Ito, and when I joined, designer Kazuo Motosawa was the head of LD.

About two years after joining LD, I had a great opportunity. I was able to visit Edison Price Lighting in the USA, which was considered a pioneer in architectural lighting. The company was founded in 1952 as a small lighting company in New York, and since then has worked with architects such as Mies Van Der Rohe, Louis Kahn and Philip Johnson to design and manufacture unprecedented architectural lighting, and truly pioneered the field of architectural environmental lighting. I was fascinated by their work, their theories and their products, so I was very impressed. Not only that, Edison Price introduced me to leading lighting designers such as Claude Engel and Paul Marantz, whom I admired.

I had learnt that there has been a profession called ‘architectural lighting consulting’ on the East Coast of the USA since the 1950s. After visiting the company, something that had been vague became clear. It was around 1980, and Japan was about 20 years behind the US.

A foothold in architectural lighting design

Mende Two years after I joined LD, the TL Yamagiwa Laboratory (hereafter TL) was established in 1980, when the goal of architectural lighting had become clear. TL was the first laboratory in Japan to focus on the design and technical support of lighting projects, rather than designing lighting fixture. There was a lot of work in architecture and interior design, and a new generation of architects such as Arata Isozaki were very active, and there were many requests for experimental lighting.

ー What kind of things do you do, for example?

Mende Architectural lighting design, developing lighting fixture, buying imported lighting fixture from overseas and designing custom-made lighting fixture. In hindsight, perhaps President Konagaya was exploring the possibilities for new Yamagiwa businesses by letting us behave freely.

ー What kind of lighting fixture did you develop?

Mende Lighting fixture is not decorative lighting products. For example, we bought the aforementioned Edison Price patent and developed glare-free downlights, and we were the first to use a then-unknown lighting technique called wall washers to uniformly illuminate walls. In short, we developed lighting fixtures as technical tools that could be used to design light itself, and introduced them to the field

ー When you say ‘design order’, do you mean you asked a external designer to do it?

Mende One day, the president told me to ask Shiro Kuramata to design a spotlight. Mr Kuramata was very close to Yamagiwa, but I didn't think he was interested in lighting fixture design, so I went to him, thinking I was in trouble. He took apart the spotlights I had brought with me on the spot and started stripping them down, saying he didn't need this and that, and then he left only the smallest parts. The result was a product called ‘K-Spot’ with only the fewest parts left. I was very much in sympathy with and inspired by Kuramata's sensitivity to light and its effects on space and objects, such as light transmission, reflection, luminescence, brilliance and shadows.

ー Before you, Motoko Ishii, who also graduated from the Tokyo University of the Arts, did a lot of work with architects as a lighting designer, didn't she?

Mende I think that the starting point for Ms Ishii and our architectural lighting is different. She has done a lot of work with the first generation of post-war architects, such as Kenzo Tange and Kiyonori Kikutake. I think those were the lighting that the times demanded and the design lighting design as her work. On the other hand, Arata Isozaki and Toyo Ito, with whom we worked, were not looking for design-oriented lighting design, but for light itself, where the light source is not noticeable. They appreciated our approach and our work. I think that the basic idea behind the work of Ms Ishii and ourselves is different. Because we are basically dealing with light itself, close communication with the designers was essential, and we approach the project with the feeling that we are working together on the architectural design.

ー Why did you quit when TL was doing well?

Mende At the time, Yamagiwa had three R&D units - the LD Yamagiwa Research Laboratory, the Yamagiwa Kosakusho and the TL Yamagiwa Research Laboratory - each employing nearly 40 staff. At one point, I was approached to join the three together to form an organisation like the Yamagiwa Research Institute, and I was asked to become the first director of the institute. It was a time when I wanted to work hard in my current position rather than in a managerial position. So I asked to retire, considering what I wanted to do and the future of Yamagiwa .

ー But wasn't it difficult for you to leave the company?

Mende There was really a lot of help from many people from the time I left Yamagiwa to set up my own company. When I resigned, Yusaku Kamekura, who worked on Yamagiwa's CI, acted as a coordinator. Five colleagues, including Yutaka Inaba and Hiroyasu Shoji, left Yamagiwa to join me. In opening the office, interior designer Takashi Sugimoto, who was well versed in real estate, found us a space in Aoyama. Ikko Tanaka designed the company logo. The reason for using the word ‘planner’ rather than ‘designer’ in the company name ‘Lighting Planners Associates’ (LPA) was because I wanted to realise light design systematically, including engineering and solutions, and we were particular about the meaning of the word ‘lighting planning’. From the beginning, I never thought of using my own name for the company name.

Embodying architectural lighting design.

ー I would like to ask you about the establishment of the LPA in 1990 and what has happened since then.

Mende After working for Yamagiwa for 12 years, I established LPA in 1990, and this year marks 34 years since its foundation. We now have four offices in Tokyo, Singapore, Hong Kong and Shenzhen, and a total team of 60 people.

ー In your book “Manner in Architectural Lighting Design”(TOTO Publishing), published in 2015, you list the concepts of architectural lighting that you have been practising: 1. light is a material; 2. lighting fixtures are tools; 3. what should shine is architecture and people; 4. learn from the rules of nature; 5. Light visualises time, 6. The function of space selects light, 7. Light creates a atmosphere beyond function, 8. Drama is created in the continuity of place, 9. Light is always ecological, 10. Light=designing shadow. This is the basis of yours and LPA's lighting design.

Mende On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the LPA, this book summarises the relationship between the ideas of lighting design and architecture through our work.

ー You have realised a great many projects over the past 34 years. We can find out more about them on our website and in books such as “LPA 1990-2015 Tide of Architectural Lighting Design” (Rikuyosha). Can you talk about some of the epoch-making projects for you?

Mende I still can't forget my first big project, the Tokyo International Forum. Three days after we founded the cpmpany on August 8th 1990, I was contacted by Raphael Viñoly and immediately went to the New York office. This project took six and a half years from basic design to completion, but we were able to realise what we had in mind without compromise. That is, while the light in earlier public spaces had to be uniformly bright, here we achieved architectural lighting that coexisted brightness, shading and warmth. Twenty-eight years after construction was completed, changes in the technological environment, such as the growth of trees and the widespread use of LEDs, have led to changes in the overall brightness of the building.

ー In projects with architects?

Mende After all, Arata Isozaki was a major presence. In 1991, when the LPA had just been established, he suddenly brought a model of the ‘Toyonokuni Library for Resources’ and came to consult on the lighting design. This was a complex facility with library and museum functions to be built in Oita City, with a 7.5-metre-high open-ceiling reading room modeled after the ‘Room of 100 Pillars’ in the ancient city of Persepolis. For us, the big challenge was how to light it, and we proposed a ‘super indirect lighting’ system that would evenly illuminate the vaulted ceiling without using downlights. It was an unprecedented plan, but Mr Isozaki adopted it and we were able to create a light environment with no shadows, which was an epoch-making job for us.

ー You have done a lot of work with Toyo Ito, haven't you?

Mende We have worked with Mr Ito on nearly 40 projects. One of the most impressive early projects was the ‘Wind Tower’ at the west exit of Yokohama Station in 1986. It was a device for ventilation, etc., but the Yokohama Urban Design Office at the time asked him for advice because they felt that a concrete tower would be too bleak. He had been focusing on light, wind, water and other elements to create a light, transparent architecture since that time, and wanted to go beyond conventional architectural concepts. He created the ‘Wind Tower’, a hypothetical small structure in which the exhaust vents are covered with a thin membrane to make their presence less noticeable, and at night they are lit with light. After that, we did the architectural lighting for his masterpieces 'Sendai Mediatheque' (2000), 'Minna-no Mori Gifu Media Cosmos' (2015) and 'Mito Civic Hall' (2022) and many other projects. For 'Gifu Media Cosmos', Arup cooperated on the day light, and LPA did the artificial lighting. Here, Mr Ito was thoroughly committed to sustainability and set a target of halving the building's energy use to half the normal level, so we pushed the envelope too.

Minna no Mori: Gifu Media Cosmos (2015) Design : Toyo Ito & Associates,Architects

ー What are some other impressive projects with architects?

Mende Hara Hiroshi's ‘Kyoto Station’ was also a big project. The location was Kyoto, so the theme was the uniquely Japanese shaded space and light as described in Junichiro Tanizaki's ”In praise of shadows”, and as a result we were able to realise architectural lighting with energy-saving effects. Overseas, the basic lighting design of the ‘China Central Television (CCTV)’ in Beijing with Rem Koolhaas. This building was being built for the 2008 Beijing Olympics, but a fire delayed its completion. The meetings with Rem and the OMA staff were exciting and enjoyable, but it was a pity that the construction supervision contract could not be renewed and we could not witness the final adjustments.

ー Do you get inspired by your dialogue with architects about light design?

Mende Of course. But I want to fulfil my role as a lighting professional and I want our proposals to inspire architects. If I don't agree with their requests, I want to say ‘that's not right’ and suggest ‘this should be done better’. For this reason, we study a lot on a daily basis and prepare well for our presentations. In fact, when architects are willing to listen to our opinions and suggestions, it stimulates discussion and leads to better ideas.

From architecture to urban lighting design

ー What prompted you to expand your field of activity to urban lighting?

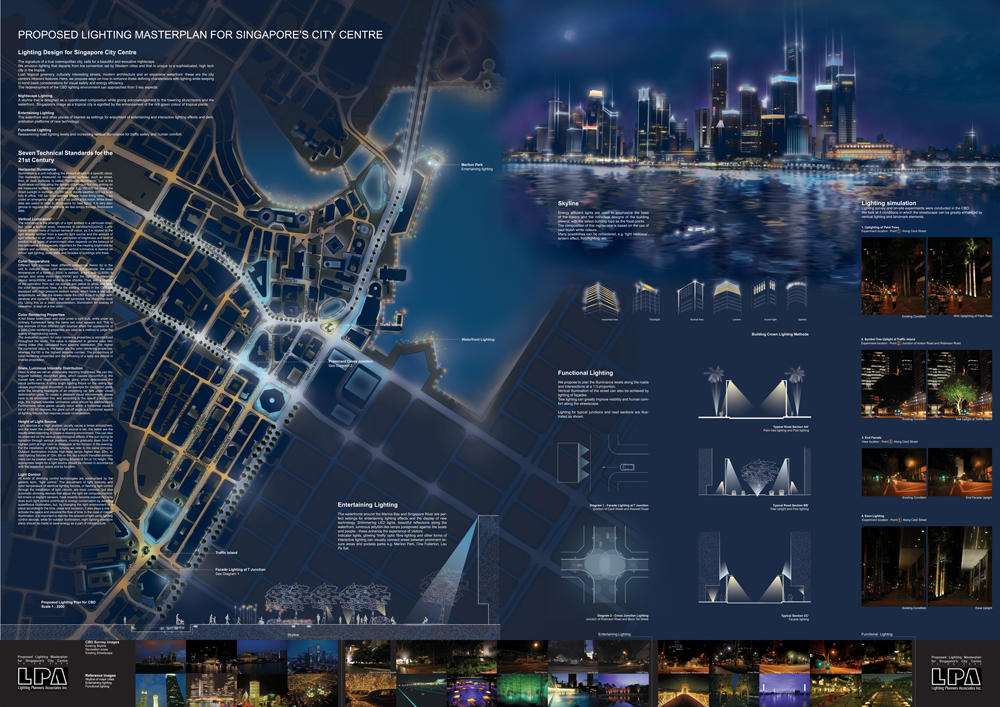

Mende In 2000, I opened an office in Singapore to take on a new theme. Soon after, we were consulted by the Urban Redevelopment Authority of Singapore (URA) on a master plan for city centre lighting, and we worked on the master plan from 2003 to 2006, and we wanted to reflect Singapore's identity - its climate, history, folklore and cultural diversity - in its urban lighting and executed.

In fact, before this, we had done the lighting plan for Zaha Hadid's ‘Urban Plan for One North District’. At that time, we proposed ‘Evolving Nightscape’. In other words, the future of urban lighting is not about the arrangement of street lights, but about the kind of light that fills the entire city, and to realise this, we had to first produce guidelines and rules and work with a perspective of 10 to 20 years into the future. With this track record, I was put in charge of the lighting plan for the City Centre and am currently creating a nightscape for the emerging city of Singapore, with a target completion date of 2030.

Lighting Masterplan for Singapore City Centre (2006)

Integrated Consulting: Urban Redevelopment Authority of Singapore (URA)

ー What was the plan for the urban lighting?

Mende The basic plan we submitted was: 1. cool and refreshing at night because of the tropical climate; 2. rhythmical light and shadows created by the intense daylight; 3. freshness at night with the unique tropical vegetation; 4. diverse light because of the country's multi-ethnic population; and 5. landscape and lighting design that utilises the waterfront. Currently, the concept is being broken down, paying attention to the quality, colour, intensity and focal point of the light in the urban space.

ー I'm looking forward to seeing it completed.

Mende When it is finished, it will be the epitome of urban lighting design. Because this project is a plan that is about the urban landscape and appearance, it is about the quality of the city itself. We have done many projects in Singapore and Hong Kong, and recently in Japan we have done urban lighting projects in Nagasaki, Yanagawa and along the riverside in Osaka.

ー All of the projects in Singapore are on a national scale and change the concept of urban lighting design, and are a kind of infrastructure development?

Mende Yes, those urban lighting projects are on the scale of civil engineering works. In Singapore, the government sees light design as an important factor in urban planning. In this process, I feel the momentum of Singapore as a nation that is 50 years old.

In urban landscapes, half of the day is spent at night when there is no sunlight, so how to design the night landscape is an important issue for urban management. Also, while sunlight is uncontrollable, lighting can be controlled by humans. That is why consultation and agreement with the people living there is essential for urban lighting. Urban lighting is not just about creating a safe and secure city. If the urban landscape becomes more beautiful at night than it is during the day, everyone will feel happy. That is why it is important to start and continue with basic rules for urban lighting to create a beautiful appearance for the city.

ー I think that there are many examples of lighting design that pollute the landscape, such as the extreme lighting and strong colours that are used to attract visitors.

Mende We must denounce such excessive examples. Recently, 'light pollution' has been attracting attention in Japan, and the Environment Agency has begun to actively provide guidance.

ー The ‘Lighting Detectives’, which you started at the same time as the LPA, is a veritable urban lighting check.

Mende Recently, many people feel they know about lighting effects from looking at websites and printed materials, but the Lighting Detectives is a platform where you can actually go to the site, experience it and discuss it. Light, lighting, is changing, so it is not something that can be understood from a single cropped photograph. We are alive in that light.

Part of the activities of the Lighting Detectives. International and diverse activities, including research, meetings and organising events on architectural and urban lighting.

ー It's really true. We cannot live in a world of darkness without light.

Mende That's why I say, ‘Learn from natural light’. The sun provides us with a variety of light environments and landscapes throughout the day and the seasons. In order to create a world where we can live comfortably with light and shadow, it is essential to take care not to alter the biological rhythms of living organisms, including ourselves.

From the perspective of the Lighting Detectives, modern people are forced to perform biological experiments on lighting and light that could lead to serious consequences if they make a mistake. Architecture, cities and ambient lighting have that much responsibility.

About Mende's archive

ー The records of your and LPA's work are the very history of architectural and urban lighting design in Japan.

Mende I'm not keen on preserving what I've done, although the LPA does keep the necessary documents such as drawings and photographs for management and preservation after construction is completed.

ー The LPA's website itself is an archive.

Higashi Only a part of the information is available on the website. Design drawings, sketches, documents, photos and data are organised by project and recorded under common rules in the four offices in Tokyo, Singapore, Hong Kong and Shenzhen, and can be searched by anyone in the company.

Mende In addition to records, scraps of photos and reports that may be useful for future work can also be searched freely.

ー Do they include Mende's sketches and notes written by you?

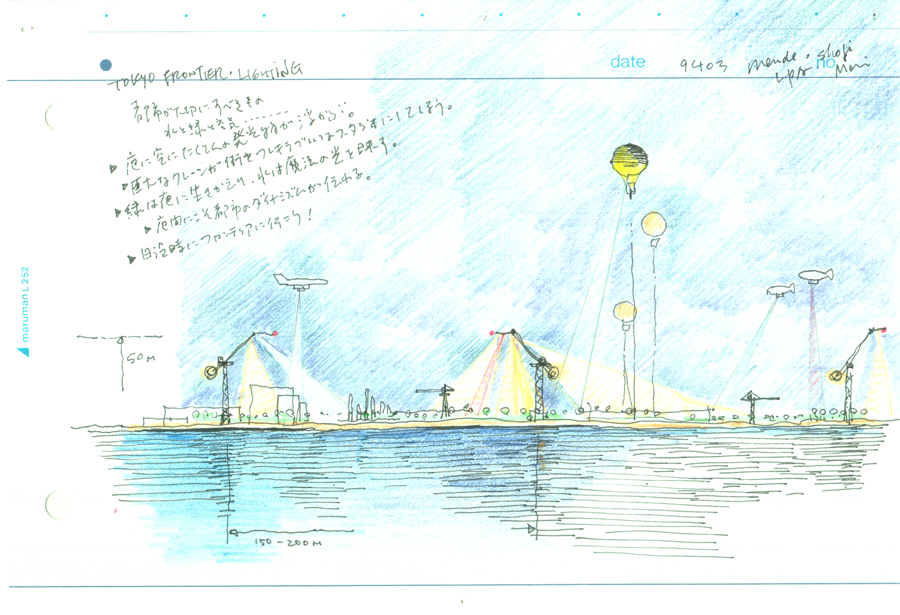

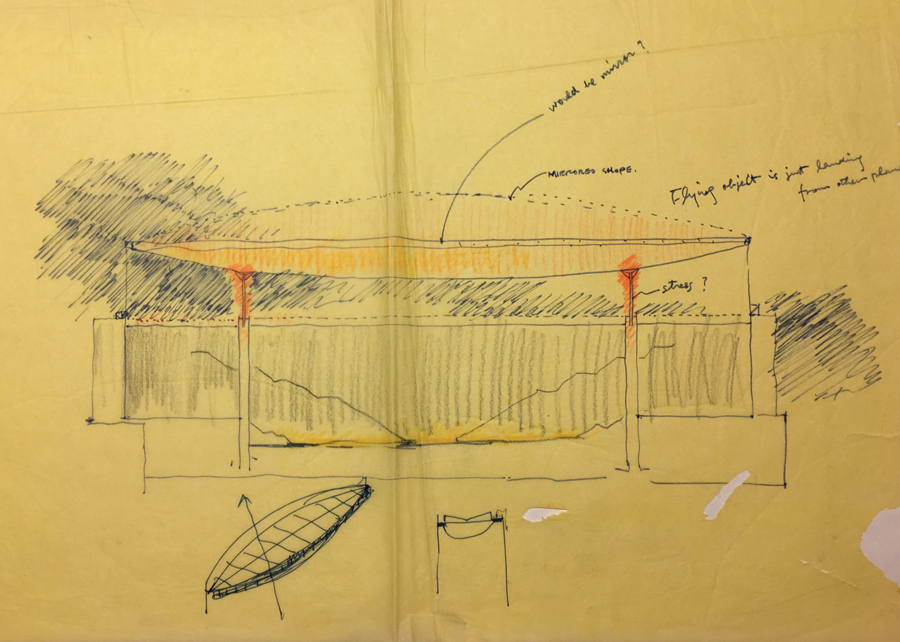

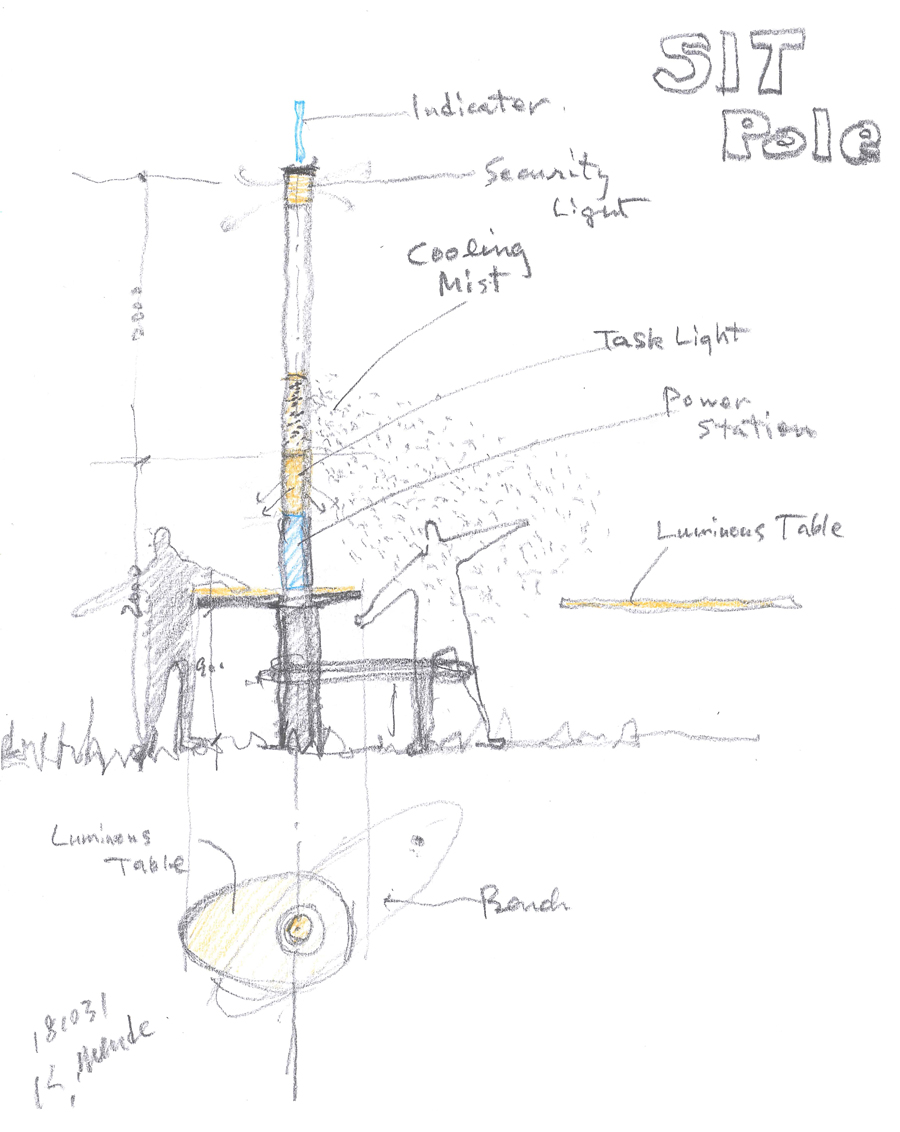

Mende My sketches and other materials were compiled after the ‘Hidden Sketches and Mockups’ exhibition, rarely seen original drawings of designers’ held at the 21_21 Design Site in 2019. That exhibition, which featured drawings, sketches and models of designs by members of the Japan Design Committee, was so well received that the duration of the exhibition was extended. This was an opportunity for me to recognise the importance of the studies and production of the design process, and I also organised and filed the sketches and original drawings so that everyone in the company could see them.

ー When do you sketch?

Mende I guess when I wake up in the morning. I'm weak at night, but when I wake up in the morning I come up with all sorts of ideas and my thoughts seem to be relatively organised. I also often draw or write down what comes to mind at meetings or while communicating with other people. Talking with people activates my mind, so I write down words and diagrams at the same time, and when I look at them later, I can trace my thoughts at that time.

Thumbnail sketches for lighting design, e.g. ‘Tokyo Urban Expo’, ‘Tokyo International Forum’, ‘Sit poles’

ー Do you share the sketches with your staff as you work on the project?

Mende At first we sit around a table and all the staff members bring their ideas to deepen the discussion, and then we talk about my ideas at the end. I incorporate interesting ideas from the staff, but at the moment my ideas are superior, so I often use them as the basis for the work. After all, I have a lot of experience and I know the sites all over the world. I also have the impression that young people today tend to think on their computers and are too aware of their surroundings. However, I am often inspired by them, and meetings and brainstorming sessions are a place for them to learn, so I use this way of proceeding.

ー What are your thoughts on design museums and archives?

Mende Museums tend to display objects with beautiful shapes and historical significance, but I don't think you can convey design with objects alone. At the very least, it is essential to show how the design was created, and of course the surrounding materials such as sketches, models and planning documents, as well as the people and places involved in the process of completion. Rather, my interest is in whether a design museum is a place where something happens. I think it is important that people not only look at the exhibits but also get involved in something, and I think it is important to create the mechanisms for this.

ー Recent retrospectives such as Akira Uno, Eiko Ishioka, Makoto Wada and Shiro Kuramata have all been very successful. But we can't even hold an exhibition if we don't have the works and the archive.

Mende That's right. The fact that the exhibition at the 21_21 Design Site, which I mentioned earlier, was a great success means that there are many people interested in such things.

ー Now, lastly, you have visited many architectures, but which one has left the greatest impression on you in terms of light?

Mende That's a difficult question. I believe that lighting design should learn from natural light, so I am often impressed by natural light such as the sky, sunsets, night skies and starry skies, or light that I suddenly discover in my daily life. In terms of architectural lighting, the light of the Philip Johnson-designed 'Crystal Church' in Anaheim, Los Angeles. Claude Engel is the lighting designer of this building. It was like a glass castle with more than 10,000 glass panels on a steel framework, and when the light came on, it looked like a giant lantern emitting light into the sky, which was very impressive. Then I liked the architectural lighting of Gunnar Asplund in Sweden, which made use of natural light. I also like the shifting light of Le Corbusier's 'Longchamp church'. Looking back now, I realise that great architecture always has great light.

ー True.

Mende Great architecture is built with light. I think architects in the past valued light. Nowadays, the things that can be done with lighting have expanded dramatically, so I fear that it has become easy to use colour and strong light to produce something. When things become convenient, they tend to become easy, so I want to be careful. Subtraction is also important in design, and some sensibilities may be lost in exchange for excessive lighting design.

ー Thank you very much for your time today.

Location of Kaoru Mende's design archive.

Contact details

Lighting Planners Associates

https://www.lighting.co.jp/