Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Makiko Minagawa

Textile Director

Date: 5 December 2024, 16:00-17:30

Location: ISSEY MIYAKE INC.

Interviewee: Executive Advisor, HaaT Director Makiko Minagawa

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

PROFILE

Profile

Makiko Minagawa

Textile Director

Born in Kyoto City

Graduated from Kyoto City University of Arts with a degree in textile design

1971 Worked at Miyake Design Studio, where she was in charge of textiles for ISSEY MIYAKE until the autumn/winter 2000 collection

1984 Worked on the ASHA BY MDS project in collaboration with Vepar (India) (continued under the HaaT brand after 2000)

1988 Published “TEXTURE: Makiko Minagawa" (Kodansha)

1990 Received the first Kujiraoka Amiko Award at the 8th Mainichi Fashion Awards

Held the "Makiko Minagawa: FABRIC" exhibition at TOTO GALLERY・MA

1995 Became a Companion Member of The Textile Institute (UK)

1996 Won the 42nd Mainichi Design Award

2000 Launched the brand "HaaT" under ISSEY MIYAKE INC., serving as the creative director

2002 Appointed Professor at the Textile Design Department, Production Design Division, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tama Art University (Term ended in July 2008; currently serves as a visiting professor)

2005 Held the "Contemporary Cloth Stoles by Minagawa Makiko" exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

2007 Received the 25th Kyoto Prefecture Cultural Award Merit Award

Began design direction for the collaborative development brand "mayu+" between Nishikawa Living and Miyake Design Studio

2014 Held the "Heart in HaaT" textile exhibition at La Collezione (Toured to Fukuoka's Resola Tenjin and Osaka's Hankyu Umeda Hall in 2015)

2018 Served as curator and supervisor for the exhibition "Khadi: The Fabric of India's Tomorrow - Homage to Martand Singh" at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT Gallery 3

Description

Description

Makiko Minagawa is a leading Japanese textile designer, widely recognised internationally. She joined the Miyake Design Studio in 1971 and for many years was responsible for the textiles of ISSEY MIYAKE. Beginning with material development, she created numerous original textiles essential to Issey Miyake’s garments. In 2000, she launched her own brand, HaaT, and has continued to explore textiles that combine craftsmanship with innovation. She has held numerous exhibitions both in Japan and abroad. Her publications include “TEXTURE: Makiko Minagawa" (Kodansha, 1988). She has received many awards, including the Mainichi Design Award, the Kujiraoka Amiko Award, and the Kyoto Prefecture Cultural Award for Distinguished Service.

Japan’s fashion industry has been profoundly influenced by Paris. Beginning with designers such as Issey Miyake and Kansai Yamamoto, the 1970s saw designers successively launching their own brands, leading to the widespread adoption of prêt-à-porter. By the 1980s, fashion had become accessible to everyone.

Issey Miyake pursued simple clothing based on the concept of “A Piece of Cloth”, which is why he was so particular about the originality of his materials. For Miyake, textiles were also the starting point for his designs. In contrast to Miyake’s creation of a unique world, Minagawa travelled to production centres in Japan and India. She applied traditional techniques and craftsmanship, which were in danger of being lost, in a contemporary manner. While researching techniques and materials handed down in various regions, she challenged herself with textile design that began with creating the yarn itself. It could take three to six months, sometimes even a year, for a material to become suitable for use in ISSEY MIYAKE. Furthermore, the work involved the added difficulty of predicting and proposing Miyake’s direction for the following season.

Though deeply knowledgeable about natural materials and traditional techniques, Minagawa was profoundly involved in the polyester tricot pleats introduced in the Autumn/Winter 1991 collection – which later became PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE – from its inception through to development and the establishment of the production system.

The design archives of the work of Issey Miyake, including the brand ISSEY MIYAKE, are managed by The Miyake Issey Foundation, established in 2004. Brands such as HaaT are preserved in an archive room created within ISSEY MIYAKE INC. (hereafter referred to as IMI) in 2019, where past work is regarded as an asset, with design data and processes also digitised. These are preserved as actual production materials and are used on a daily basis in both educational and practical contexts.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

(Clothing items refer to photograph numbers. Selected from numerous works with accompanying commentary)

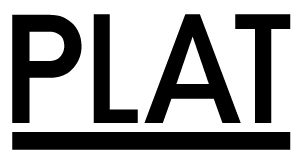

① ISSEY MIYAKE “Tattoo” (Spring/Summer 1971): A cotton jersey dress featuring a tattoo-inspired print technique (100% cotton).

② ISSEY MIYAKE “Tattoo” (Spring/Summer 1971): A cotton dress with a tattoo-patterned print depicting a dove, a symbol of peace (100% cotton).

③ ISSEY MIYAKE “Kumigasuri” (Autumn/Winter 1985): A work expressing Kyoto’s traditional kumigasuri (compound ikat, Kyoto’s traditional woven-dyeing technique) technique. It uses thick, knotted cotton woven from braided, unevenly dyed yarn (100% cotton).

④ ISSEY MIYAKE “Cicada Pleats” (Spring/Summer 1989): A shirt in organza with a translucent quality reminiscent of cicada wings. A single scarf is folded into a square, randomly pleated diagonally, then unfolded and sewn together (75% silk, 25% polyester).

⑤ PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE (Spring/Summer 1994): Clothing realised as highly functional products through a technique in which fabric is developed from a single thread, sewn into the garment shape known as “garment pleats”, and then pleated (100% polyester).

ASHA BY MDS Textiles

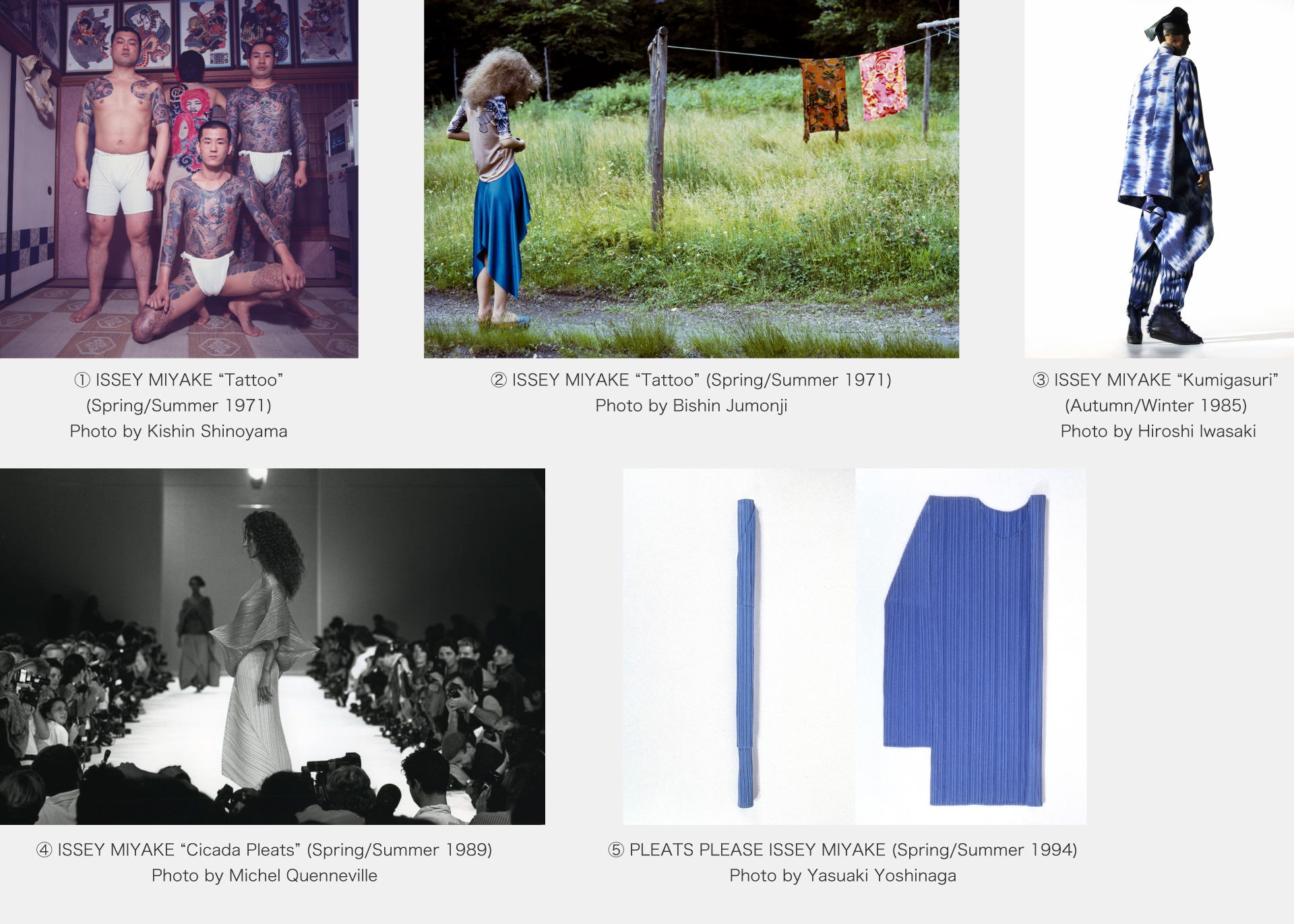

⑥ ASHA BY MDS (1987): A coat crafted from Indian tussah silk fabric with hand-kabira stitching. The padding consists of 100% cotton batting.

⑦ ASHA BY MDS (1987): A set in cotton satin with hand-kabira stitching applied to the front by Indian artisans.

HaaT Textiles

⑧ HaaT “DOUBLE TARTAN SKIRT” (Autumn/Winter 2004): A skirt featuring a jacquard weave with tartan patterns in different colours and designs on the front and back, allowing it to be worn on both sides (Cotton 54%, Silk 38%, Nylon 7%, Polyurethane 1%). A stole produced by unfolding a crepe tartan jacquard weave and finishing it at double size (Wool 38%, Silk 15%, Cotton 44%).

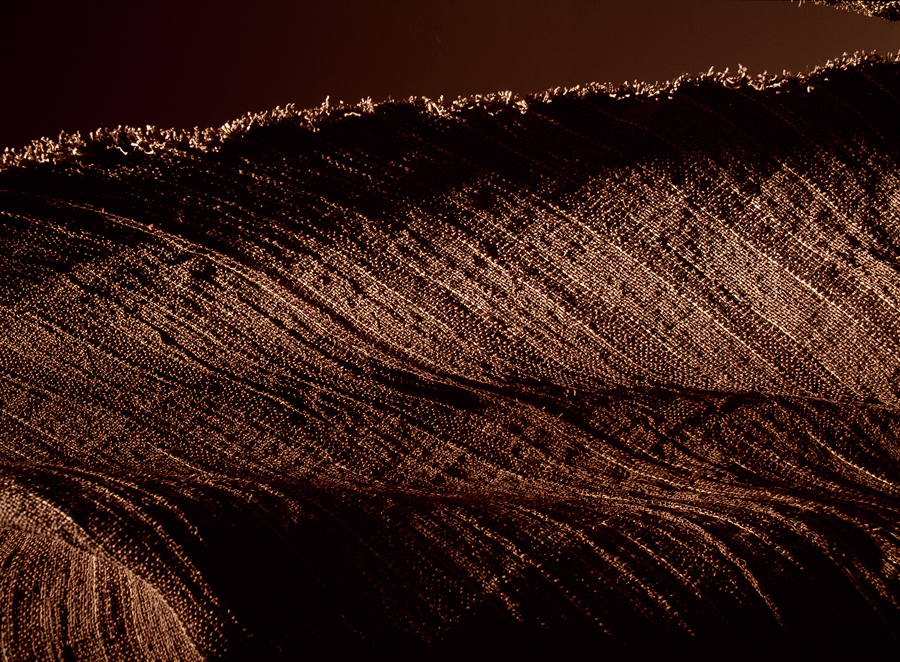

⑨ HaaT “FIRE+CHECK” (Autumn/Winter 2007): A jacquard-woven fabric combining cupra and cotton in a grid pattern, with a flame motif woven in wool. The wool sections were fulled (a process of shrinking wool fabrics to enhance thickness and texture) to create the garment’s form (Cupra 52%, Cotton 26%, Wool 22%).

⑩ HaaT “Khadi: Indian Craftsmanship” at ISSEY MIYAKE / NEW YORK (2019): Exhibition view. Fabric and dress woven by skilled Indian artisans using hand-spun, hand-woven lightweight plain weave (100% cotton khadi).

⑪ HaaT “KYO CHIJIMI HEM LINE FRINGE” (Autumn/Winter 2023–2024): Kyo chijimi features a light, supple feel and distinctive crinkled texture. To minimise skin contact points, the weft yarn is heavily twisted and woven with gaps, causing the width to compress when wet. This creates a textured surface with subtle shadows on garments (100% cotton).

⑫ HaaT “KUMO SHIBORI PARKER” (Autumn/Winter 2025): High-density taffeta fabric treated with spider-tie dyeing in Arimatsu, Aichi Prefecture – a traditional centre for shibori (tie-dyeing technique) dyeing. Portions of the fabric at the collar and cuffs are hand-tied, then the entire garment is wound into a spherical shape and bound with string. It is subjected to high temperature and pressure to set the shape. Finally, when the spider-tie knots are undone, striking three-dimensional protrusions emerge.

Exhibitions

TOTO GALLERY・MA “Makiko Minagawa: FABRIC” exhibition (1990); The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston “Contemporary Cloth Stoles by Minagawa Makiko” (2005); La Collezione “Heart in HaaT” (2014; 2015 Fukuoka, Resola Tenjin; Osaka, Hankyu Umeda Hall); 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT Gallery 3 “Khadi: The Fabric of India’s Tomorrow – Homage to Martand Singh” (2018)

Books

“TEXTURE: Makiko Minagawa” (Kodansha, 1988)

Interview

Interview

If it was something I hadn’t seen before, I’d try making anything.

Developing original materials

ー Thank you for agreeing to this interview. Today, I’d like to ask about your journey so far, your brand HaaT, and also your personal archives.

Minagawa I’m not particularly adept at looking back over the past, so I’d prefer to answer while reviewing past materials. To be honest, I disliked the idea that something I’d done before might be considered good, and I didn’t want to keep any materials at all. It felt like looking back, and I didn’t even like the term “archive”.

ー Many creators who are constantly moving forward express similar sentiments. Ms Minagawa, you worked on textiles for Issey Miyake for 30 years.

Minagawa Miyake has always maintained that clothing creation isn’t a solitary endeavour; new clothing emerge through teamwork and collaboration with staff. He permitted his staff to discuss how they worked with him. He was inclusive, or rather, he would say that we backstage staff could do whatever we wanted. He was someone who simply couldn’t rest until he was moving forward, ever forward.

ー Ms Minagawa, you were born in Kyoto and graduated from the Kyoto City University of Arts (formerly Kyoto City University of Fine Arts), Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Textile Design. Even while a student, you had your own studio and worked as a textile artist.

Minagawa Even as a student, I had a small dyeing studio and was creating textiles. At that time, Pop Art was entering Japan and new art forms were emerging rapidly. I too wanted to incorporate ideas for mass production into textiles, rather than sticking to the traditional dyeing and weaving methods that only allowed for one-off pieces. I was seeking connections to study in London.

ー Let’s hear about your encounter with Mr Miyake. Mr Miyake went to Paris in 1965, experiencing the era when Parisian fashion shifted from haute couture to prêt-à-porter. In 1968, he witnessed the May Revolution. He later described seeing the people rising up as the origin of his approach to making clothes.

Minagawa Miyake studied clothing design in Paris and New York, returning to Japan determined to present his own clothing. In 1970, there was a show in Kyoto organised by Toray where multiple designers presented their work, and Miyake participated. I saw it, and his clothes were outstanding. I was so moved that I visited him backstage. At that time, when I mentioned my desire to go to London to study, he said, “The future lies in Japan. I need someone to handle fabric design, textiles.” He then added, “I want to develop durable workwear to replace jeans. I need your help.” So I postponed going to London and started by living in Kyoto, taking on work on a project basis. Later, Miyake told me, “You are in charge of textiles.”

In April 1970, Mr Miyake established the Miyake Design Studio, and Ms Minagawa took charge of textiles for the brand ISSEY MIYAKE from 1971.

Minagawa At that time, the term “textile design” was not yet commonplace, and no other designer employed a dedicated textile designer. It was an era when designers selected and designed from fabrics provided by fabric suppliers. Miyake was quick to recognise that fashion design also required original textiles, stating that he wished to begin by creating original fabrics. In other words, my role was to create unprecedented, original materials – Miyake had identified the work of creating original materials.

From a teamwork perspective, Mr Miyake rarely spoke in detail about what specific work his staff were doing. Yet I sense that he himself saw new possibilities for clothing in Ms Minagawa’s textile expressions.

Minagawa He always insisted that even though I was called a textile designer, I was creating textiles for clothing. Miyake was someone who never concealed who was responsible for what. In 1985, Miyake Design Studio published a book titled "Issey-tachi" (ISSEY MIYAKE & MIYAKE DESIGN STUDIO 1970-1985, Obunsha), which compiled interviews with all the staff members at the time.

What I shared there was that Miyake wanted to proceed by the shortest route possible, so he would pose questions like a Zen kōan. If Miyake said, “White in winter”, I would ask what kind of white, narrowing it down.

ー So it wasn’t about simply doing what you were told, but teamwork in which each person had to explore something new.

Minagawa I too always wanted to create new materials. The work begins with deciding the thread colour, the count, and making the thread. We determine the weaving structure, the pattern, dye the threads, and weave them. Then we apply finishing processes and decide the surface treatment. From my idea sketches, the raw materials are spun, the threads are dyed and woven, becoming fabric. Then, through Miyake’s design, it becomes clothing.

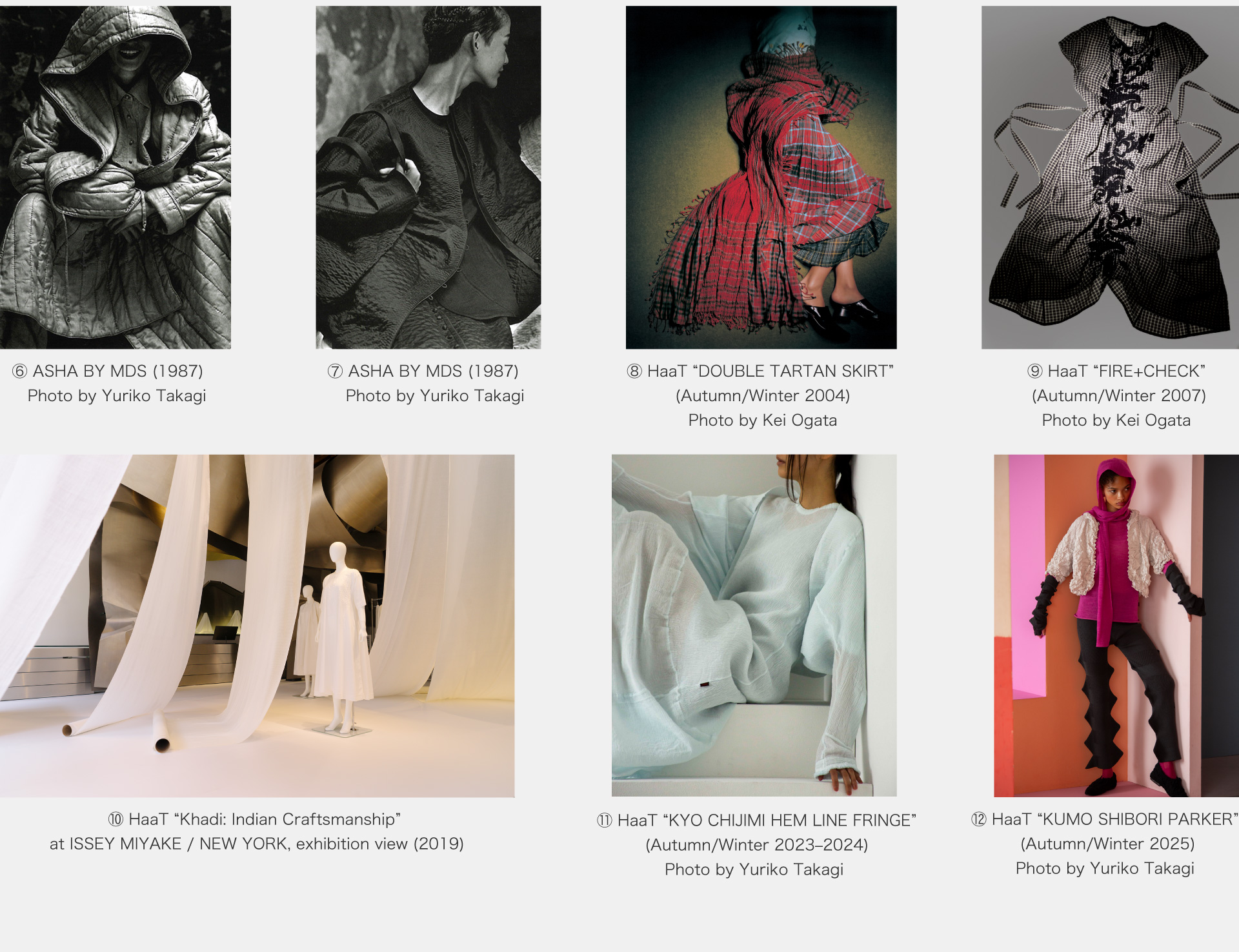

A double-weave technique using lurex and wool yarns, producing distinct patterns on the front and reverse.

Cotton fabric replicating banana stem fibre, finished with a technique that imparts a linen-like texture to cotton.

Textile featuring a grid of loom yarn and Shetland wool subjected to fulling. All three: Produced in 1984. Photo by Keiichi Tahara.

The Difficulty of Making Proposals Ahead of Time

ー Does clothing design begin only after the textile design is completed?

Minagawa At that time, yes. Which made it all the more demanding.

ー So you would develop textiles for the next season and present them to Mr Miyake. You had to be prepared in advance.

Minagawa The most important task was to anticipate what Miyake might be interested in for the coming season, or even the following year. If I proposed something that did not capture his interest, it would simply go to waste. What kind of music or artists might he be drawn to? Would it be Asia or Africa in terms of region? What kind of natural world, what colours? He was an intuitive person with a very keen antenna, so I tried to work out which people fascinated him at that particular moment, and use that as a starting point.

My very first project for a collection was on tattoos. Miyake had always been fascinated by tattooing as part of traditional culture, and from the beginning he was very conscious of the body. Every few years the body would emerge as a theme. One day he suddenly took me to the tattooist Mitsuaki Owada and said he wanted to create a T-shirt around this idea. I had no experience and no idea where to start, so I went to a film studio in Kyoto and found the people who applied tattoo make-up for films such as Toyama no Kin-san or the yakuza films starring Sumiko Fuji. I watched them closely and learnt how to create effects such as colour gradations.

ー That was the Tattoo collection with Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin as motifs. Later you also created dresses featuring a floating pterosaur and Marilyn Monroe. It is fascinating to hear how you responded to Mr Miyake’s sudden and difficult challenges.

Minagawa I had to imagine what Miyake might be thinking. I came up with textile ideas based on what interested him, otherwise the direction would be off. Fashion is dull if it fails to capture the spirit of the time. And it is a world that has to be completely renewed twice a year. We produced about 500 materials in a single year.

I, and the other staff as well, simply wanted to please Miyake. Everyone thought hard and brought him ideas. That was the nature of our relationship. He never made distinctions between men and women; if you had ability, you would be given responsibility regardless of gender or age. The price was that every day was full. We would go out with the models and key staff to Shinjuku and talk until late at night. It was often hard to say whether we were working or playing, but life at that time felt as if it ran twenty-four hours a day.

Inspiration from the Everyday

Minagawa Miyake said he wanted to develop robust cotton fabrics that could only be made in Japan, present them at Paris Fashion Week, and propose everyday wear. Having studied textiles in Kyoto, I knew some artisans there, so I contacted them and went to meet them. We researched fabrics such as tabi sock material, sashiko stitching, Aomori kogin (Aomori kogin embroidery, traditional sashiko stitching), yōryū (a crêpe-like fabric), and men’s shōhana cotton (a traditional cotton cloth for men’s kimono lining), commissioning new materials to be created. In the 1970s, ISSEY MIYAKE was not yet well known and production runs were limited, so placing orders was difficult; we even took sake to the workshops to persuade them.

At that time in Japan, many weavers specialised in the widths used for kimono fabrics rather than clothing fabrics, so we also approached them. Fabrics with the weight per unit area suitable for kimono were standard for us, but for people overseas they were unusually heavy. Western clothing has established standards for weight in grams per square metre for shirting, jacket fabrics and coat fabrics, which are highly codified. Since textiles were viewed through these fixed standards, fabrics of moderate thickness like Japanese kimono cloth were unusual. It caused quite a stir overseas as well.

ー So you selected Japanese fabrics with overseas sales in mind?

Minagawa Exactly. We travelled to factories all over Japan, searching extensively. We experimented with various techniques: kasuri (ikat weaving technique), shibori (tie-dyeing technique) dyeing, Japan’s distinctive nassen printing (Japanese stencil dyeing technique), and finishing processes. We did not use the techniques as they were; we altered the yarn usage and incorporated design to develop the materials. During the 1980s and 1990s, a Japan boom swept the world, and ISSEY MIYAKE sold extremely well. No matter how many garments we made, they continued to sell.

In the late 1970s, our collaboration with Tadanori Yokoo also began. We asked Mr Yokoo to create paintings, which were then dyed at Lake Como in Italy and subsequently finished using Japanese discharge printing techniques. Mr Yokoo has continued to design the invitations for the Paris collections ever since.

ー It was also an era when Japan’s craftsmanship and design took flight globally, buoyed by economic prosperity.

Minagawa For me, anything I saw could become a theme; everything around me was a source of inspiration. I sought to utilise materials inspired by things that moved me in daily life, particularly noticing much from nature. This meant creating textiles from anything Japanese that foreigners might not know about, from ginkgo leaves to straw mats. I would replace the texture of hemp in bashō-fu (banana-fibre cloth) with wool, or unearth the ordinary. I often visited the warehouses of textile factories. They contained failed prototypes and discarded samples. Even in the scraps of fabric left in the corners of those warehouses, I sensed potential and a kind of human warmth and affection.

ー I’ve heard that discovering things discarded in factories became something of a tradition at IMI. I imagine you were extremely busy, yet you meticulously documented that period.

Minagawa As the scale gradually expanded, interactions with the factories also changed. Communication with the weavers was crucial in every instance; mastering the machinery was never one-way. Every detail of those exchanges – how to place orders for mass production, how to refine the finishing – has been preserved. This began around twenty years ago, I think. The term “archive” started appearing then, and I truly detested that word; I simply could not accept it.

ー I see, I understand (laughs).

Minagawa I only want everyone to see the finished product. The most passionate and crucial parts of our exchanges are all jumbled up like rough notes – I wouldn’t want anyone to see them. I don’t want to show the wrestling process; I want to come across as cool, don’t I? So I kept pleading with them to discard all those files, but the archive manager stubbornly refused to listen and has kept them all.

ー From your perspective, that must be truly frustrating. But for those viewing it, seeing the brilliance of the finished piece is one thing, yet witnessing the trial and error behind it creates a story. It makes the impact all the more profound.

Minagawa Each day, in one way or another, hectic exchanges took place. For roughly 30 years, from 1970 until the creation of HaaT in 2000, the textile work carried out at ISSEY MIYAKE has been preserved by the foundation in precisely this manner.

Reviving India’s Traditional Craftsmanship

Minagawa In 1985, an event called “India Year” was to be held in France. The Indian government contacted Miyake about it and requested that he create garments for the occasion. So we travelled to India together, and in order to source fabrics we ended up journeying extensively throughout the country. Miyake grew fond of India and became deeply interested in its craftsmanship. While researching Indian handicrafts and hand-spun cotton fabrics such as “Khadi”, he met Mrs Sarabhai (Asha Sarabhai), owner of the Calico Museum. She had established a brand centred on the skills of craftsmen and household tailors. Seeing her work, Miyake proposed collaborating on fashion in India and creating things together. That marked the start of their work in India.

ー That was the brand ASHA BY MDS, launched in 1984. Ms Minagawa oversaw this brand for 15 years.

Minagawa In 1999, Miyake decided to hand over the role of designer for ISSEY MIYAKE to Naoki Takizawa (until the Spring/Summer 2007 collection). I felt it would not be right for me to continue working on textiles with Takizawa under those circumstances. So I decided to step away from the ISSEY MIYAKE work at that juncture, in 2000. That was when I launched my current brand, HaaT. Takizawa excels in synthetic fibre design, so while we had previously focused on cotton fabrics and production in those regions, the use of synthetic fibres would likely increase thereafter. The work with weavers, which had continued for decades, would cease. I felt that would be a pity, so I decided to start a new brand centred around natural fibres.

HaaT “PRE OUTER KABIRA” Autumn/Winter 2024

ー Without work, techniques like dyeing and weaving cannot be sustained. Viewed another way, the skills and knowledge of weavers and artisans themselves are vital archives. Ms Minagawa initially mentioned she was uncomfortable with the term “archive”, yet she strongly recognised the importance of preserving these techniques and knowledge. And as a textile designer, she took a new step to put this into practice.

Minagawa There were also practical challenges. When the same system continues for decades, ideas inevitably start to dry up. Looking back, the experience of France’s “India Year” in 1985 became a turning point in that sense.

Moreover, as part of the changing times, manufacturers themselves were becoming reluctant to use such fine fabrics. The advent of lightweight, breathable, stretch polyester fabrics such as those for “triathlon wear” meant there was less inclination to use heavy, draping fabrics. The 1988 exhibition Issey Miyake A-ŪN at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris represented both the culmination of Miyake’s work in the 1980s and the final chapter in his approach to clothing design from the 1970s to the 1980s, which prioritised luxury, complexity and substantiality.

It was within this context that PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE was born. Research into pleating techniques began in 1988. In fact, I was involved in this work too.

The Origins of PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE

ー When the brand PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE was launched in 1993, it caused a major sensation in both the fashion and design worlds.

Minagawa I handled almost everything during the start-up phase – from the mechanism of creating the pleats by pressing the fabric, to deciding on Toray for the yarn, where to outsource the knitting, and negotiating lot sizes with the companies. At that time, I had also begun to tire of solely creating elaborate, “impressive” materials. I found excitement in establishing new systems. We expanded from producing materials in 100-metre units to 2000-metre units, initiating work with new textile mills. We focused on reducing costs, establishing mass production systems, and determining the most efficient companies for each stage of textile creation. That system still functions today, and I genuinely feel it was worth establishing.

Miyake himself also wished to further develop his existing approach to production. By chance, I was creating scarves using a method of post-processing garment pleats – sewing the fabric first and then applying the pleats. Miyake saw this and took a liking to it, declaring that this single piece could become a garment. That was the catalyst.

"PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE" 1994 Spring/Summer Catalogue

ー So Ms Minagawa was responsible for one of the starting points of the pleating concept, and the foundation for its mechanism was also being shaped.

Minagawa But I never imagined it would become clothing. With scarves, I worked on them so that if you folded one up, it wouldn’t crease when you unfolded it. When you turn this into clothing, interesting forms emerge, moving in various directions. Though synthetic fibres are cheaper than natural materials, pleating them requires three times the usual amount. Feasible for scarves, but prohibitively expensive for garments. The production side is ruthless, so Miyake was always asking, “Can’t we make it cheaper?” I conducted extensive research myself on how to reduce costs.

ー So transforming that small spark into a revolutionary product required layers of ingenuity. That process astonished me.

Minagawa Lightweight and perfect for travel. Wrinkle-free. PLEATS PLEASE became the alternative to jeans that Miyake had envisioned. But actually, during development, the male executives in charge of business didn’t understand its value. Women like myself pleaded, “This will definitely sell, please make it a brand,” yet it still took three years before it could stand alone as a brand.

The Birth of HaaT

Minagawa From 2000 onwards at HaaT, I began overseeing the overall direction while collaborating with our technical team. We design through three distinct approaches: “EVERY MONTH” proposes original designs born from skilled craftspeople; “EVERY WEEK” offers high-quality, functional pieces that are easy to incorporate; and “EVERY DAY” provides everyday wear that adapts to seasonal and temperature changes. We even developed fabrics such as one spun from fine cotton yarn twisted over 200 times.

ー Given your established reputation as a textile designer, you could have left IMI to launch a new brand. Why didn’t you?

Minagawa Perhaps it was a lack of leeway. The textile knowledge and experience I gained over those 30 years were cultivated within ISSEY MIYAKE; I didn’t feel I could freely utilise them. That’s why I chose to launch a new brand from within this company.

ー Having your own brand brings further changes, doesn’t it?

Minagawa Previously, I only needed to create things that didn’t exist in the world. But owning my own brand brings with it the responsibility of selling. After experiencing the pandemic, I came to feel it was important to create clothes people could wear daily.

HaaT features simple silhouettes infused with diverse artisanal materials. We also focus on creating products designed to catch the eye – such as those rolled up and placed beside the till, tempting customers to pick them up. Another HaaT signature is our India-exclusive series, crafted by skilled artisans at the Sarabhai workshop in India, showcasing techniques unique to that country.

Making Things by ISSEY MIYAKE INC.

ー Was there a particular reason why Mr Miyake entrusted the creation of the ISSEY MIYAKE collections to the next generation from the Spring/Summer 2000 season onwards?

Minagawa I don’t know the reason, but perhaps he had created the pleat and his perspective was shifting towards broader design and product creation. Or maybe, wanting to glimpse more and more new, unknown worlds, he chose to walk alongside the young people whose seeds he had sown, hoping for their rise. But he was always looking far ahead, someone for whom there was no end. So perhaps he was also thinking about what would happen after he was gone.

This also marked a turning point for various changes. IMI's new headquarters were established in 2000, and from that point all technicians began using CAD. This enabled the complete digitisation of patterns, with the data archived as a valuable asset. This means we no longer need to start draping (the pattern-making process) from scratch. Instead, we can reference the accumulated CAD data and build new patterns based on past knowledge. It’s not just about the CAD data; here, we share the entire process. The creative output isn’t dependent on individuals; it’s considered a shared asset.

ー That’s wonderful. What kind of system do you use to store the archives?

Minagawa Work with Miyake is managed by The Miyake Issey Foundation (2004–present), while HaaT work has been stored in the archives room as part of IMI since 2019. We consult the foundation on preservation expertise and follow their protocols, photographing items and digitising data. There are about five staff members in the archives room. We also have dedicated space for data photography. Both personnel and budget are specifically allocated for the archive.

Packaging, warehouse temperature and humidity, and pest control are all strictly managed. When we request a specific year’s samples from the digitally archived materials, they arrive the very next day. After wearing them, we return them cleaned. While we might grumble about the archive, actually using this system reveals its brilliance. The archive allows us to learn from past work and gain valuable insights.

ー Was this initiative started by Mr Miyake?

Minagawa Not solely him. It stems from the company’s people embracing the idea early on that their work constitutes an asset to be shared.

ー In this era dominated by fast fashion, your meticulous craftsmanship, Ms Minagawa, has become truly precious. Finally, I’d like to ask about the future of HaaT.

Minagawa Thankfully, there are people who appreciate this kind of craftsmanship and are willing to support it. Furthermore, there are still many wonderful Japanese textile techniques and superb Indian handcrafts that remain largely unknown. I hope to introduce these skills, even if only gradually. As we primarily operate on a made-to-order basis, we do not produce items that become waste and are discarded once the season ends. Nevertheless, we must also consider reducing our environmental impact.

The fashion cycle is fast, placing significant strain on production sites. Many factories struggle immensely to meet deadlines. To avoid overburdening factories, we set production start dates as early as possible. Heightening sensitivity in preparation and time allocation in order to keep pace with Miyake’s vision of “the future” – this remains an enduring asset passed down at IMI.

ー There has never been an example quite like this of utilising archives to such an extent and actually applying them to the craft of making things. Thank you for sharing such an immensely insightful account.

Enquiry:

NPO Platform for Architectural Thinking