Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Takuya Onuki

Creative Director, Art Director, Graphic Designer

Interview: 23 June 2025, 14:00–16:00

Location: Onuki DESIGN

Interviewee: Takuya Onuki

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Takuya Onuki

Creative Director, Art Director, Graphic Designer

1958 Born in Tokyo

1980 Graduated from Tama Art University, Department of Graphic Design.

Joined Hakuhodo

1992 Won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity

1993 Established Onuki DESIGN

2003 Received the Mainichi Design Award

2015 Appointed Professor, Department of Graphic Design, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tama Art University (until 2024)

2022 Received the Yusaku Kamekura Award

Principal Awards

Numerous awards including Tokyo ADC Awards (Member Award, Member's Highest Award, Grand Prix), Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity (Grand Prix, Gold Lion, Silver Lion), New York ADC (Gold Award, Silver Award), and many other awards.

Description

Description

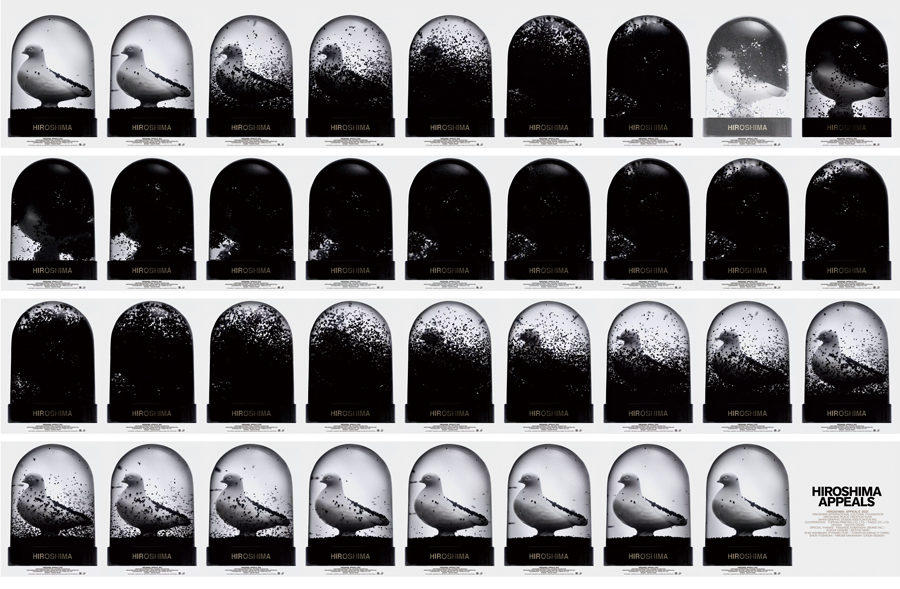

‘Mr Onuki possesses the extraordinary ability to make the impossible possible,’ wrote Noriyuki Nakajima (CM director), who teamed up with Onuki for the Cup Noodles commercials, in one of his columns. True to that description, his work includes: - Toshimaen, derided as ‘the worst theme park in history’; - Cup Noodles, depicting the origins of eating with mammoths and cavemen roaming freely; - Pepsi Cola, featuring the original Pepsi Man alongside Star Wars characters; SoftBank, where Cameron Diaz embodies the arrival of a new era; Shiseido TSUBAKI, conveying the beauty of Japanese women through straightforward means; and Hiroshima Appeal, where a snow globe's white dove is covered in pitch-black ash. Every advertisement created by Takuya Onuki delivers its message head-on.

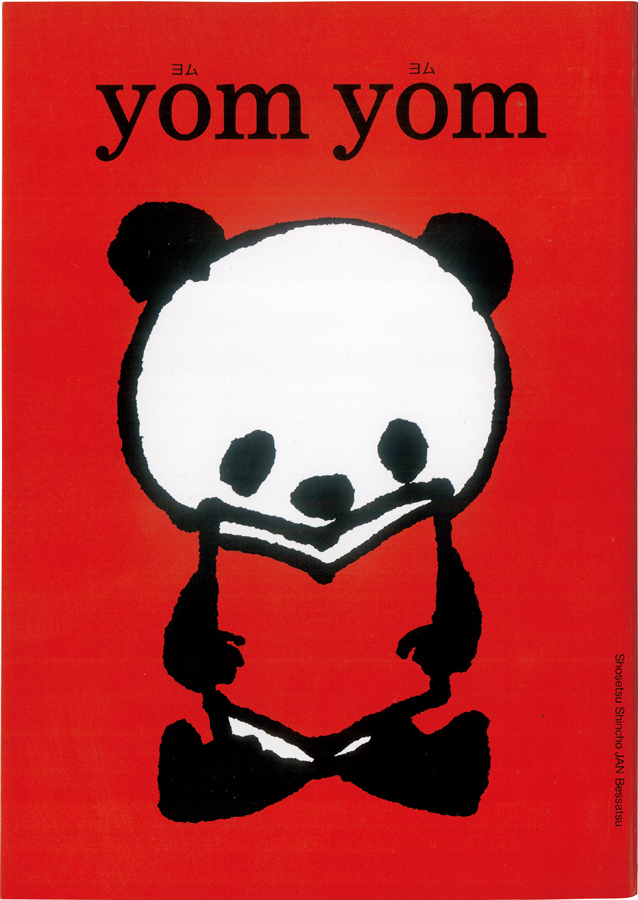

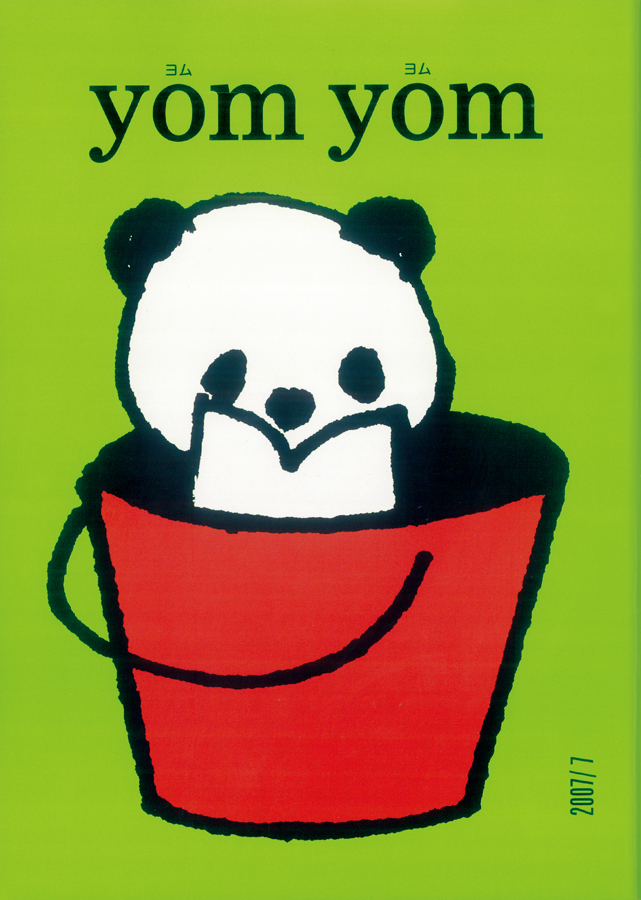

That's not all. Onuki pioneered new techniques in advertising. For instance, as part of campaigns, he developed and sold numerous novelty items and character merchandise. For Pepsi, customers flocked to stores eager to get their hands on Pepsi Man and Star Wars novelty items. At Shinchosha's “Yonda?”, initiatives like hand-drawn style promotional pop-ups, proposing ‘paperback frames’for bookshop displays, and the art director-conceived paperback ‘yom yom’ incorporating graphics, opened up new readerships. These signified a leap from the two-dimensional world of advertising, printed matter, and film, transforming from something seen into something experienced.

In the era when Japan was hailed as “Japan as Number One” and the whole nation was swept up in a festive frenzy, and in the era when the festivities ended and digital technology began transforming people's thoughts and actions, Onuki unleashed advertising that made people's hearts skip a beat. He did so with bold ideas, an artisan's meticulous precision, and a cold, penetrating gaze that cut through the world.

The Onuki Design studio we visited for the interview is a concrete fortress-like building nestled within a residential area of Kita-Aoyama. Stepping inside, one is immediately cut off from the surrounding clamour, entering a space conducive to creative concentration. What surprised me was that Onuki was working on his design projects at a computer, sharing a desk with his staff! The interview took place at a large table positioned in the centre of the workspace. Feeling somewhat apologetic for taking up his valuable time for the interview, he spoke candidly for over two hours about advertising and Japanese creativity, drawing on his own experiences.

Masterpiece

Works

Advertising ‘Toshimaen Amusement Park’ (1982–1995)

Advertising ‘Laforet Harajuku’ (1990–2003)

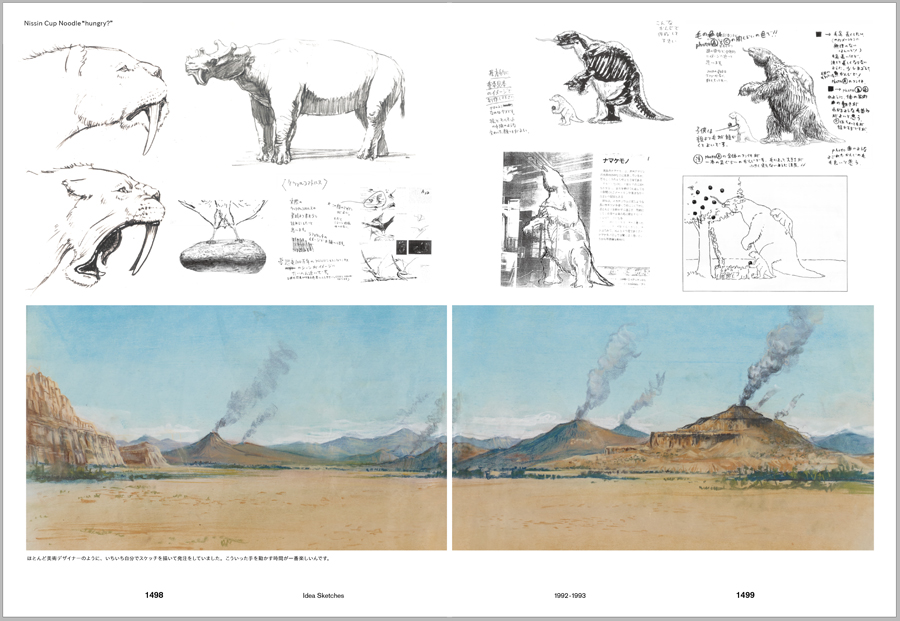

Advertising ‘Cup Noodles’, Nissin Foods (1992–1996)

CI ‘J.League’ (1993)

CI ’FM Yokohama’ (1995–2000)

Advertising ‘Pepsiman’ Pepsi Cola (1996–2004)

Advertising ‘Shincho Bunko Yonda?’ Shinchosha (1997–2013)

Logo ‘Expo 2005 Aichi, Love Earth Expo’ (2000)

Advertising ‘SoftBank’ (2006)

Advertising ‘TSUBAKI’, Shiseido (2006–2011)

Poster‘Hiroshima Appeals’ (2021)

Publications

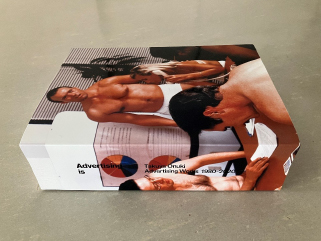

Koukoku Hihyou Special Edition 7: “The Complete Works of Takuya Onuki”, Madora Publishing(1992)

“Advertising is Takuya Onuki Advertising Works 1980-2010”, Graphic-sha(2017)

New Edition:“Advertising is Takuya Onuki Advertising Works 1980-2020”, CE Media House(2020)

Interview

Interview

My Work: 5% Ideas, 95% Execution

Ideas Alone Don’t Lead to Success

Unprecedented Work Collection: 6cm of Creative Power

ー Today we wish to discuss the creative philosophy and archive of advertising's maverick. We'd like to begin with the collection that stunned the publishing world, “Advertising is - Takuya Onuki Advertising Works” – truly the definitive archive of your work. What prompted its publication?

Onuki It was over 30 years ago now, but in 1992, strongly encouraged by Yukichi Amano and Michiko Shimamori, I published a book titled The Complete Works of Takuya Onuki as a special edition of the magazine “Kokoku Hihyo”

ー So The Complete Works of Takuya Onuki was well received?

Onuki Yes. For some time afterwards, both of them kept suggesting we should do a second volume, but I was far too busy to even consider book production. Before long, Ms Shimamori passed away in 2013, followed by Mr Amano, leaving the project in limbo. Yet it remained in my mind as a task they had set me. Ultimately, over twenty years passed.

ー You also wrote the text, didn't you?

Onuki Initially, it was Amano's idea that I should lecture Hakuhodo's young designers and compile the sessions into a text. But after several attempts, we scrapped it because the content felt superficial and half-baked. I thought, well, wouldn't it be quicker if I just wrote it myself?

ー “Advertising is” was finally published in 2017, a quarter-century after the first instalment, and won the Tokyo ADC Award in 2018.

Onuki We began preparations with the same policy as “The Complete Works of Takuya Onuki” – to include every single job. But the sheer volume of work meant just organising it took years.

ー Having seen the book, I was amazed you managed to organise such a vast amount of work.

Onuki The publisher told me that expensive advertising portfolios wouldn't sell. It was a time when advertising had completely lost its vigour in the world. They said an affordable book prominently featuring the word ‘design’ would sell well. Being someone who always starts by rejecting things, being told ‘advertising portfolios won't sell’ was hugely stimulating. So I decided: forget trying to gloss it over with the word ‘design’. I'd deliberately stick with the word ‘advertising’. I'd deliberately make it a thick, exaggerated book like a telephone directory. From there, I finalised the format: paper quality, page count, font size, and so on.

I wanted text to fill 80% of the pages, but I realised that was impossible and abandoned the idea. Even so, it contains about the same amount of text as three standard books. It's over 1600 pages, with small type and dense content. I resolved that ordinary people didn't need to read it; only those who genuinely wanted to, or understood it, should read it. I deliberately made it a book that goes against the grain, refusing to pander to the times.

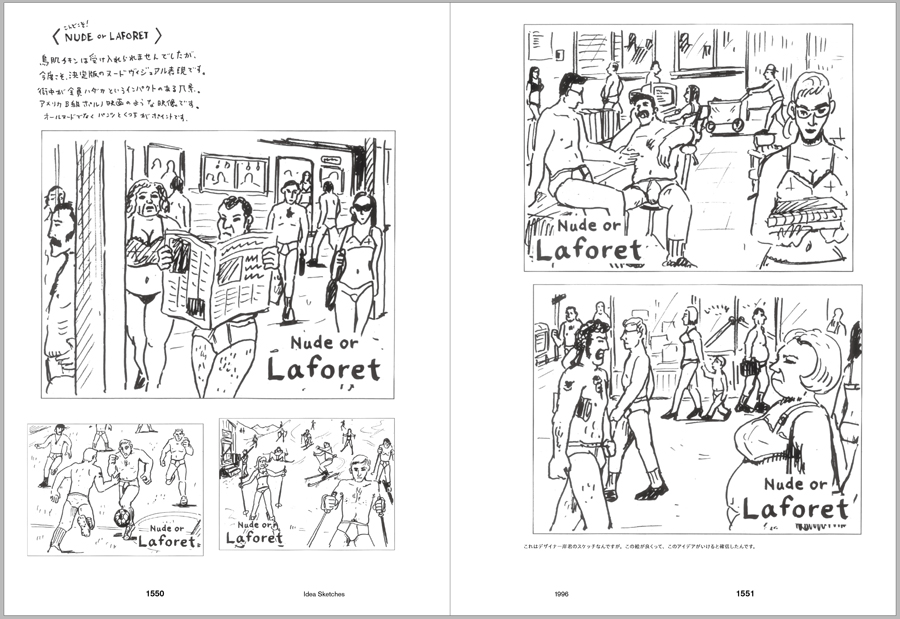

ー The 2,500 copies of the 2017 edition of “Advertising is” sold out in no time, and I finally managed to get hold of a copy when it was reprinted in 2022. What surprised me was that the latter half of the book, around 250 pages out of 1,630, generously featured handwritten storyboards and sketches. As a reader, you want to see not just the finished product but also what lies behind it.

The overwhelming “Advertising is,” like a telephone directory. The latter half is packed with storyboards and sketches—especially those created for Laforet Harajuku and Pepsi (from “Advertising is”).

Onuki Rough sketches were particularly well-received in “The Complete Works of Takuya Onuki” too. I’d kept my own roughs and sketches rather than discarding them, so it was good they could be put to use.

ー How do you feel about preserving your own works and materials?

Onuki For the publication of “Advertising is”, I consciously kept the physical works and handwritten rough sketches.

ー Unlike posters or logos, rough sketches and storyboards are crucial as communication tools during the production process for advertisements.

Onuki To convey the behind-the-scenes process of conceiving an advertisement—which is almost like a game, almost like play—to young people with a sense of immediacy, it's vital to show not just the finished product but the intermediate stages too.

ー The resulting portfolio was truly ‘phone book’ in both size and weight, conveying Onuki's profound dedication.

Onuki The current advertising industry is in a serious slump, lacking vitality. I feel the term ‘design’ is being used like a saviour to pull the wool over people's eyes. That's precisely why I stubbornly refused to use the word ‘design’. I deliberately titled the book “Advertising is”, not “Design is”. Media, styles, and methods may change, but the essence of advertising as communication never does. That was my intention – to send a rallying cry to the advertising industry.

ー “Advertising is” is also a record of Creative Director Takuya Onuki's own growth, isn't it?

Onuki When I first entered this industry, advertising creatives were highly celebrated, but I lacked conviction. So I resolved to become the kind of art director I believed in, and have faced my work with utter sincerity ever since. That stance remains unchanged. In “Advertising is”, I've organised my journey and struggles as an art director into three parts: ‘The Era of Pursuing New Expression’, ‘The Era of Business Focused on Delivering Results’, and ‘The Era of Ambition Demanding Strong Purpose in Expression’.

ー I was astonished by your memory in your meticulous descriptions, and I found it to be first-rate design theory.

Onuki I don't proceed with work based on vague notions like ‘it's something like this, right?’ or ‘this looks nicer, doesn't it?’. There is a reason behind every idea, design, visual, and copy. That's why I remember every detail of the entire process. So, I've simply faithfully reproduced the entire journey of what I've done and thought, without injecting any assertions or proposals into the text – merely ruminating on the facts.

ー So that vast amount of information is stored in your head?

Onuki In my work, I meticulously consider each step and logically construct the production process. Because everything has a reason and justification, I believe I can always pull explanations out of my ‘mental filing cabinet’. Plus, working in advertising means you constantly have to persuade others, so writing copy becomes second nature. I was actually surprised myself that I could produce such a volume of text, even though my use of particles like ‘te-ni-wo-ha’ was still rather vague.

ー The rough sketches in the latter half offer a glimpse into the behind-the-scenes of advertising production.

Onuki Though the old sketches were hand-drawn, the digital ones just don't seem as interesting when printed in a book.

The finished image is clearly discernible.

ー Do you currently design digitally from the outset?

Onuki Using a computer, skipping hand-drawn sketches and creating something close to the final product from the start is overwhelmingly faster. That said, tracing the thought process is crucial, so my stockpile of rough data is enormous and the files are downright maddening. I felt the same when ‘Illustrator’ came out – computers keep expanding your thinking, so it becomes limitless. In my case, if the entire job is 100%, I spend about 5% on the idea itself, and 95% on the work to bring it to fruition. Ideas alone cannot lead to success.

ー Is that like fitting each puzzle piece into place one by one?

Onuki No, it's more like meticulously hand-drawing a single picture, filling every corner with precision. I take pride in being able to visualise the finished image with certainty. To realise that image exactly, I obsess over every detail, resulting in an immense workload. It's precisely the simplest ideas that demand the most precision.

Sketches for ‘Cup Noodles’. Onuki enjoys the most when he's using his hands, and he personally sketches every detail before placing an order. (from "Advertising is")

ー They say ‘God is in the details’. Is that sensibility of yours innate?

Onuki Oh, no, that's not it. I think it's the mountain of information accumulated within me and the sheer number of drawers to store it in. Ever since my junior high, high school, and university days, I've simply adored anything new, possessing stronger curiosity and admiration than anyone else. Consequently, I've seen and heard an enormous amount, and it's all seeped into my very being. Nowadays, information and products are everywhere, but people just glance at them online and feel like they know something, when in reality, nothing has truly entered them. What truly matters are those experiences that make your soul go “thud!” – that profound impact. I think I have so many drawers precisely because I've had far more of those “thud!” moments than most. Though, come to think of it, I adored encyclopaedias from childhood, so perhaps my powers of observation and curiosity were always above average.

ー So you're selecting and combining useful elements from these drawers?

Onuki In today's world overflowing with objects and information, I believe pure originality no longer exists. Therefore, what truly matters is the “editing ability for purpose” – choosing what to select from countless elements and how to combine them. This manifests as the “habits” of discernment and aesthetic sensibility I've cultivated over time; this is what constitutes my unique sense.

Subsidence of creativity

ー Last year (2024), there was an exhibition at the Setagaya Art Museum (‘Museum Collection I: The Work of an Art Director — Takuya Onuki and Yasuji Hanamori’), and it seems your work was acquired for the collection.

Onuki It was an exhibition initiated by the museum following the acquisition of my work. I simply selected pieces and arranged them for the given walls. Initially, I wondered if past advertising work would hold any interest, but seeing them all lined up proved surprisingly effective. Because, gazing at the displayed pieces, an era revived where immense effort, time, and money were lavished on a single advertisement. That sensation felt fresh even to me. It meant that mere advertisements had matured and transformed into historical records. That, conversely, is probably because today's advertising is nothing more than mere “leaflets”. Even in printing, the dedication and craftsmanship of the past have vanished, replaced by flawless printer output.

In 2024 , an exhibition ‘Museum Collection I: The Work of an Art Director — Takuya Onuki and Yasuji Hanamori’ was held at the Setagaya Art Museum. Currently, the museum holds a collection of 108 works by Onuki, including posters.

© Setagaya Art Museum Photo: Ueno Photo Office

ー Indeed, that sense of excitement from back then is absent.

Onuki When I started working in the 1980s, it was a unique era forged by our seniors. They were purely pursuing novelty and expressive possibilities. Within a globally isolated, Galápagos-like situation, many uniquely Japanese advertising works emerged. I simply inherited that legacy, made it functionally effective as advertising, and further liberated the framework of advertising methods. Today's advertising is like newspaper insert flyers that unilaterally state what they want to say.

ー What do you think is the cause of the current dullness?

Onuki Primarily the client, I'd say – the client's mindset. There's an element of gamble in creativity that theory can't cover, but lately, everything seems data-driven, with preconceived conclusions from the outset. Underlying this is a trend where fear of risk prioritises ‘avoiding failure over achieving success’, leading to more people making decisions based solely on data and evidence. Since no one wants to take responsibility for failure, advertising becomes perfectly adequate as a “leaflet”.

ー So you're saying creative professionals lack decision-making power and authority?

Onuki Yes, that's right. At some point, creatives became mere craftsmen. Creative directors used to be at the heart of the creative process, wielding significant authority. Recently, however, creative roles have become fragmented and flattened. The focus is no longer on the success or impact of the advertising, but on project efficiency and avoiding failure. While the flattening of the hierarchy might be a positive development, it means everyone only considers their own area of responsibility, leading to short-term priorities taking precedence.

ー But nowadays, many people don't know about the Galápagos era or when you started working...

Onuki Exactly. Depending on your perspective, the current state might be considered the norm. Recent advertising isn't particularly interesting, but you can understand what it's trying to convey. It's true that in our passionate era, excessive creativity often resulted in baffling adverts, and many became talking points without boosting sales. That's precisely why, as an art director, my policy was to create adverts that generated buzz while also driving sales. Saying this might sound like I'm dismissing those who came before me, but that's absolutely not the case. Perhaps it simply reflects how the role and expectations of commercials evolve with the times.

Creation Begins with Negation

ー What is the origin of your advertising ideas?

Onuki For me, creation begins with negation. Because if the current state is good, there's no need to change it. Furthermore, I believe that if the product is good, advertising isn't necessary. After all, it's possible to artificially boost sales through the power of advertising.

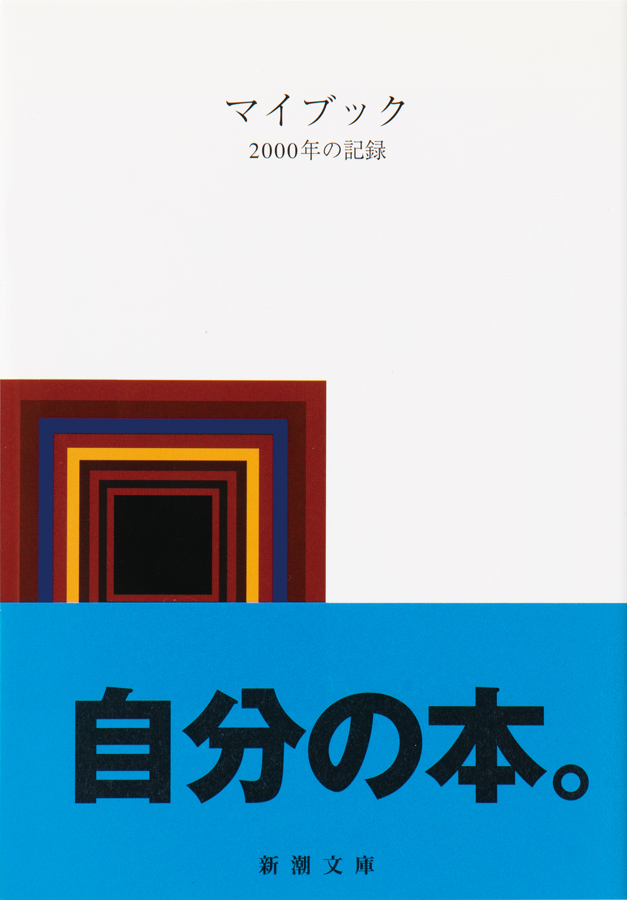

ー Come to think of it, you were involved in product development with an advertising mindset, weren't you? For instance, Shiseido's ‘TSUBAKI’, SoftBank Mobile's PANTONE® series, and Shinchosha's novel magazines ‘yom yom’ and ‘My Book’ – I understand these were products born from an art director's perspective.

The product was born from the creative vision of an art director, combining SoftBank's PANTONE® series with the cover designs of Shinchosha's publications ‘My Book’and ‘yom yom’.

Onuki Nowadays, it's become commonplace for art directors to discuss products, and more companies seek design proposals. But back then, it was unthinkable for advertising people to venture into that territory. While some of my proposals were realised, I also lost jobs precisely because I ventured there. In my case, the main reason for leaving wasn't failing to deliver results, but friction arising from trying to change the core issues – the organisation and its systems. For them, it was likely a case of ‘we didn't want you going that far’. From my perspective, I thought they should have just made better use of me.

ー That sounds very much like Onuki, who won't rest until he's done something thoroughly.

Onuki That meant I couldn't take on a lot of work. As a designer, I think it was inefficient. Particularly in advertising, when I was both creative director and art director, I was involved in absolutely everything from the initial idea through photography, illustration, sets, models, make-up, costumes, lighting, copy, direction, right down to the music. Looking back, though, I do have some regrets. Because I did everything myself, I think it was impossible to hand over the work properly once I moved on.

Shiseido and ‘Hiroshima Appeals’

ー What projects stand out most for you?

Onuki For me, advertising work is a kind of game, so I found them all enjoyable. It’s about figuring out how to solve the problem before you—the harder the puzzle, the more fun it is.

ー In that sense, what would you say was a particularly enjoyable project?

Onuki Toshimaen project was the one that created the biggest turning point for me, but that’s a long story, so perhaps I’ll mention another project instead. Shiseido’s ‘TSUBAKI’ was quite a challenging project.

ー Around the time you started working with Shiseido, you wrote in “Advertising is”: ‘Shouldn't advertising think more for society and consumers? (omitted) It may sound presumptuous, but isn't guiding companies the role of the art director going forward?’ Was that related?

Onuki Shiseido was once an aspirational company for creators, boasting overwhelming brand power, but that power had significantly waned. The brief for that project was to launch a new product into the stagnant shampoo market and achieve a dramatic turnaround. My initial thought was that it was crucial to simultaneously cultivate the new shampoo into a top brand and revive the long-established “Shiseido” brand itself. However, once I actually got started, it proved an extremely difficult task. Refreshing an uncool image to achieve results is easy, but restoring the prestige of a company like Shiseido, which had once enjoyed such glory, is no simple feat. That's precisely why it was so rewarding.

ー Meaning?

Onuki I believed that now was precisely the moment for Shiseido to reposition its new shampoo product as one created by Japanese people, for Japanese women, and to rebuild the brand by placing the aesthetic sensibility of “the very heart of Japan” at the forefront of its message. Given this, the product name could only be “椿 = TSUBAKI(Camellia)”. This is because the camellia is Shiseido's symbol, camellia oil has been a vital ingredient used since ancient times for Japanese women's hair and skin beauty, and the camellia itself embodied the independent woman desired for the coming era. From this, the packaging, commercials, posters, and billboards were all created using imagery symbolising the camellia.

ー The commercials featuring Japan's top actresses at the time were truly spectacular. Now then, what work outside of advertising stands out in your memory?

Onuki The ‘Hiroshima Appeal’s campaign was a project that required considerable resolve. The atomic bomb issue is an extremely sensitive subject. I wondered: was it really appropriate for someone like me, who grew up without deep awareness of war or the atomic bomb, to take it on? After pondering it for a while, I reconsidered and thought that perhaps precisely because I was like this, it might be worth trying. Similarly, I took on that work for Shinchosha because I thought my very lack of reading might make me suited for it. So, perhaps by tackling the atomic bomb myself, I could deliver the message to a wider audience. If so, then there might be meaning in me doing it. But I knew I absolutely couldn't produce a half-hearted design. I had to firmly construct my own stance and resolve to remain unshaken by any opinion.

ー In 2022, Onuki's ‘Hiroshima Appeals’ exhibition at Creation Gallery G8 was truly spectacular. The heavy scent of rubber chips covering the floor stirred unease, allowing visitors to experience the atomic bomb not just visually but through all five senses. The cutting-edge AR* expression was also highly impressive.

*Abbreviation for Augmented Reality

“Hiroshima Appeals,” a project that explored four-dimensional expression through the use of augmented reality (AR).

Onuki The poster's main visual features a snow globe containing a white dove, a symbol of peace, and black powder. When you hold your mobile phone over the poster, the AR activates, filling the space with black powder that envelops the white dove. However, eventually the black powder settles to the bottom, and the white dove reappears. Through AR, I wanted to introduce a fourth dimension (time) into the two-dimensional poster, enabling contemporary viewers to relive the atomic bomb and the black rain. I utilise both analogue and digital techniques, but what they share is a commitment to meticulous craftsmanship throughout the process. Yet, in the final output, I take care to ensure the viewer doesn't perceive the labour involved in its creation.

ー I hear the special snow globe used on the poster is being commercialised.

Onuki Yes, we have a prototype ready. However, stable mass production is proving difficult, and numerous challenges remain regarding sales infrastructure and inventory management, preventing its realisation. We'd love to sell it at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, or perhaps market it as an art piece.

The Impact of AI on Design

ー How do you think digital technology and AI will effect design?

Onuki Put simply, it means designers and art directors will see their fees steadily dwindle to nothing (laughs). Unlike humans, getting AI to design costs nothing. Recently, an AI-generated film that would have cost around ¥300 million previously was produced in just 15 seconds with zero budget.

Previously, to become a designer, you had to study design fundamentals at art college, be skilled at sketching, possess good taste, and be able to draw various elements by hand. Now, however, all it takes is tapping away at a computer keyboard and clicking a button, so even amateurs can produce passable designs. Since anyone can become a designer, design work floods the streets, and even advertising can get by with mediocre execution. I get the feeling that TV commercials aren't even expected to be laboured, time-consuming pieces anymore. And in the end, it doesn't matter which one it is, and I lose interest. It's the

same thing over and over.

ー What might happen as AI becomes more involved in design?

Onuki AI is evolving daily, so visuals in particular will become riddled with fakes to the point where nothing can be trusted. The world will turn surreal, and people will lose interest in entertainment.

Looking back, when CGI first appeared in Hollywood, we were astonished by its dynamic visuals. But now, the value of those Hollywood-style jaw-dropping effects has diminished.

Current AI uses these as templates for re-editing, so impressive-looking visuals and art can be produced with ease. But once that becomes commonplace, people will lose interest.

ー What do you think people ultimately desire at the end of this path?

Onuki Ultimately, I reckon people will come to prefer the simple, analogue normality. For instance, family trips to play in beautiful rivers, or having drinks at home with like-minded friends – I think people will realise these things are far more enjoyable, and that’s probably already happening. From now on, excessive entertainment like we've seen before might reach a dead end, and conversely, society could improve. Of course, there will always be a certain number of people wanting to make a quick buck within the traditional framework, but I think more people will step off that stage and seek enjoyment and happiness within their means, even if they don't have much money.

ー Did you taught at Tama Art University. In times like these, what do you convey to your students?

Onuki I taught design through dialogue with students. I would present a brief, then guide them through their ideas and designs from a creative director's perspective, just as I would in my regular work – offering feedback like “this doesn't quite work” or “try this approach”. I believe the lessons were designed to let them experience that sense of achievement when they found the answer.

When I entered the advertising world, newcomers would first tackle jobs that seniors avoided, before being entrusted with more playful, adventurous campaigns. Yet this process wasn't wasted; it was a crucial period for building ideas and skills. Nowadays, however, people often skip this grounding experience, skimming over the vital aspects of design – ideas and expression – and it's somehow accepted. To me, it seems people today can't even create a proper leaflet anymore.

ー Earlier you mentioned “flyers” – what is the true intent behind them?

Onuki For instance, suppose you were tasked with designing a flyer to “double the takoyaki stall's sales in a week” – a struggling shop near the station. You could probably create a neat, stylish design, but it wouldn't contribute to sales. It's rather a pity that skipping the experience of making straightforward flyers is being overlooked. What matters isn't stylish design, but ideas and methods that achieve the objective. Nowadays, there's no opportunity to hone the skills needed to get to the heart of that essence.

ー In “Advertising is”, you wrote that while pondering an advert for Toshimaen, you were inspired by a sign at a ramen shop saying ‘Cold noodles now available!’ and conceived your signature piece, ‘The pool is chilled’.

Onuki When I joined Hakuhodo, the creative meetings in my department back then dismissed designs that looked good but made no sense. That experience honed my ability to think critically. For someone like me, who had lived solely chasing novelty and judging things by whether they looked cool or not, it was a revelation. It also sparked me to keep asking: what exactly is my form of expression? If we view advertising as communication, then putting up a handmade sign saying ‘Cold noodles now available’ at the shopfront is far more effective than distributing thousands of leaflets that look cool but make no sense. This experience taught me to always start by asking, ‘Is this really the best approach?’ and to question the very form of past advertising. That remains my fundamental starting point.

ー That's something AI can't do, is it?

Onuki Occasionally I see promotional items designed by AI, but I find them rather lacklustre. They're merely compilations of past data, so they haven't reached the stage of “making a mark” in new areas. But the day AI achieves that is surely not far off.

ー So what should designers do going forward?

Onuki One direction is to establish a position more closely aligned with companies, becoming involved with products themselves. That means participating in the proper approach of integrating brand, design, and advertising solutions directly within the product itself. Another path is becoming a craftsman, akin to an artisan. Essentially, it’s about embracing that world of subtle, craftsman-like dedication. Currently, creatives dominated by those who think solely in numbers and data hold sway. But I harbour the hope that if a smash hit emerges suddenly from a completely different perspective—like a mutation—it might instantly shift the prevailing trends. Ultimately, people are the source of value. I hope that original individuality, which only that person can express, will break through.

ー What does the future of advertising look like to you?

Onuki I believe it's not that advertising has become ineffective, but rather that the old formats no longer work. Recently, influencers have taken on the role once played by advertising, so advertising hasn't lost its value. However, I am concerned that agencies, finding influencers more efficient, are allowing their creative capabilities to weaken.

Conversely, future advertising will likely be produced proactively by companies and local authorities. For students, working for manufacturers, local governments, or leading regional firms – developing products, creating adverts, collaborating with communities to revitalise towns – offers far greater creativity and appeal than agency work. While businesses and administrations have paid high design fees for advertising and branding, much of this will be replaced by AI.

ー I keenly feel how the environment surrounding design and advertising is undergoing drastic change right now, with the advent of AI and shifts in distribution.

Onuki That's right. The dominance of convenience stores and fast-food chains is growing. Because they control the retail space, they can take products painstakingly created by manufacturers and designers, tweak them, and sell them in huge quantities very quickly. There's little room for genuinely innovative newness there. Meanwhile, manufacturers are caught in a vicious cycle: they're forced to develop a vast range of products just to secure shelf space in places like convenience stores, leading to a decline in the market share of their core products. I believe the positions of manufacturers and distributors have completely reversed.

Moreover, in this era of overflowing goods and information, accelerated further by AI, ordinary people make choices and decisions based on reasons like “it's recommended by an influencer” or “it's highly ranked”. Many people likely find researching vast amounts of information and products bothersome, and consider spending time on such choices a poor use of time.

ー How should we restore creativity in the present day?

Onuki I believe Japan, having lost so much in its relentless pursuit of novelty, must now seriously reconsider its culture and what it means to be Japanese. That conviction drove me in designing the symbol mark for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Tradition and the classical are not outdated; they are cultural legacies passed down through the ages, serving as archives that reveal the very essence of our times. “Novelty” is no longer the sole virtue. While saying “things were better in the old days” might sound like the sigh of a grumpy old man, I want to positively embrace that sentiment in every sense and rebuild Japan's creativity and culture.

ー I've always found Onuki's advertising work uplifting, so hearing about the source of that creativity had my heart racing. Thank you for today.

Location of Takuya Onuki's Collection

Setagaya Art Museum:https://www.setagayaartmuseum.or.jp/