Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

University, Museum & Organization

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office)

Date: 27 June 2019, 13:30 - 15:00

Location: Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office)

Interviewees: Keiko Ueki (Curator, Osaka Museum Construction Preparation Office)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki and Akiko Wakui

Author: Akiko Wakui

Description

Description

After more than 30 years of preparation, the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka will finally open in 2022*. The museum already has a collection of more than 5,700 works of modern Japanese and Western art, as well as contemporary art and design, which will be fully exhibited from April 2022.

When I visited the museum in June last year, Mr. Tomio Sugaya, Director of the Preparation Office, gave me a valuable talk on the origins of the museum and an overview of the archiving project in the field of design.

The museum's archives include the Gutai Art Association, Japan's oldest advertising agency Man-Nen-Sha, and the advertising distribution magazine "PRES ARTO". The museum also acts as the secretariat for the Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP), which was set up to collect and disseminate information on industrial design products, particularly consumer electronics.

For this interview, we visited Ms. Keiko Ueki, Deputy Director of Research, who is responsible for collecting and organising information on IDAP, and spoke to her in more detail about her specific work and the problems she faces.

*Postscript, December 2021

Interview

Interview

An archive is only a warehouse if it is not stored, organised and published.We need to think carefully about whether this is something we can organise and manage ourselves.

Background to the establishment of IDAP

― When we visited the museum last year, we talked mainly about how the museum was established and its design collection. This time, we would like to hear more about the archive project.

The Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP), of which you are the secretariat, collects information on industrial design products, especially consumer electronics. First of all, can you tell us about the background?

Ueki IDAP's activities began with an industry-academia-government collaboration project launched in autumn 2014 with the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office), Panasonic and Kyoto Institute of Technology. As a public museum in Osaka, we had to decide where to focus our collection of post-war design. So we decided that in the Kansai region, which is known as the "Kingdom of Home Appliances", we could not do without that part of our collection.

However, it is physically impossible to have a comprehensive collection of household appliances. So we came up with the idea of a structure where we would work with companies that were preserving their own products, collecting this information and the museum would act as a platform. Two years later, we developed the project into a council in order to work with a wider range of companies and research institutions.

Gathering information from actual objects and oral histories

― When it comes to industrial design archives, the number of products alone is enormous. In addition, there is a wide range of related materials, such as blueprints, brochures, etc. How do you gather information?

Ueki Basically, our approach is based on the actual product, which is still available. As I found out when I started, in most cases there are no design drawings left. In order to check the details of the product, I sometimes consulted the information on the design registration, but there is a specific way of writing the design registration, which is slightly different from the actual product. If the item is still in existence, it can be measured and labeled with the product number and other information.

If a company doesn't have the actual item, I look for the item left by an individual, so I am gradually unravelling it. It's surprising how little information there is. In the beginning, I thought that there would be too much information, so I set up 120 survey items, but I have never filled them all.

― That's 120 items? You collect and record them all by yourself, don't you?

Ueki The total number of bilingual items is 120, so the content is half that - 60. In the case of industrial design, it is not enough to say that the material is plastic, so I try to include technical information such as molding and surface treatment methods. 60 items are not enough, but it is still a lot more than for a work of art, so it is not easy to go on alone.

― Is it possible to find out all the information about the material and processing by looking at the actual product?

Ueki The designer who developed the product told us that even if he could manage to find out what the material was made of, the older the product, the more the details of the processing and the invisible parts could only be known by the developers of the time. So I decided to carry out an oral history to find out how the product was developed. However, many of those involved in the development of the 1950s and 1960s have unfortunately already passed away. Although I have been able to talk to those who are still alive, it is impossible to reconcile the information I have obtained from the oral history with the information I have obtained from the actual objects, so I have decided to treat both types of information as different and to accumulate what I can.

― Oral history are you the only one who does this?

Ueki In some cases, I work alone, but in other cases I work on the interview with the help of a current employee of the company or an retired designer of the research collaborator. However, the work remains in my hands after the interview. At the moment, I have interviewed about 20 people, but the records just keep piling up. Sometimes I ask part-timers to do the transcriptions, but I haven't quite managed to get them into a publishable article or report yet.

I also found out that it is difficult to record in the same way a complete product, which is called an appliance, and an infill product, such as building materials, interior decoration and wiring. Therefore, we have separated infill as a subcommittee within IDAP, and are working with the ex-employees of Sekisui House. Even so, there are only two of us, and now the activities on the appliance side tend to stagnate, so I would like to proceed with more collaborators in the future.

A huge amount of work that is not visible from the outside

― You have to visit the developer while he's still alive, and with the huge amount of research to be done, it's a lot to keep up with.

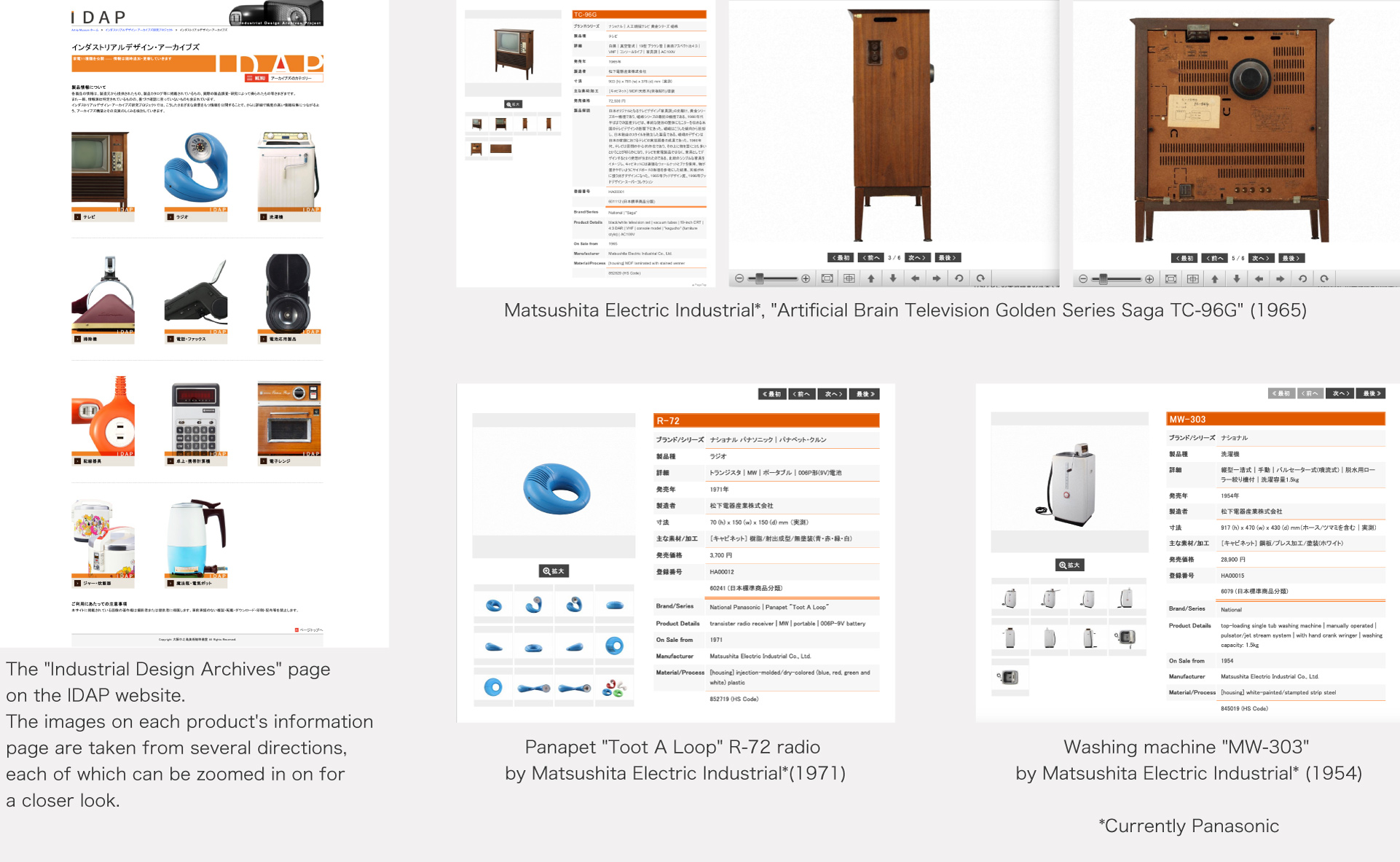

Ueki Although the number of products is still small, we currently have an IDAP page on the museum's temporary website, within which we have published some of the information, together with photographs of the products, on a page called "Industrial Design Archives" (http://nak-osaka.jp/idap/archives.html). The information contained in this section is extracted from the main information management database and includes only those items that are required for publication, such as year of release, dimensions, main materials and finishes, price, etc. For example, the information in the "main materials and finishes" section is a simplified version of the information on materials and finishes registered for each detail of the product in the information management database. I have been working hard to fill in the fields in the information management database, but there is still a lot of information that has not yet been registered.

― You do a huge amount of work behind the scenes that is not visible from the information on the surface. Do you still have a lot of design drawings and technical documents that provide such detailed information?

Ueki We also have a section on design drawings and design registrations, but as I said before, these documents are not easy to find unless the developer has kept them, so I don't fill them up very often. Most of the material I have left is customer and promotional brochures.

― Did you also take the photos?

Ueki I tell them what to photograph, but I hire professionals to do it for me. For a catalogue for an industrial design exhibition I did, I photographed the entire surface of the product, and it was very well received. It was then that I realised that there is a lot of information that can be conveyed by photographing not only the front of the product, but also the back, sides and five or six other aspects. That's why the photos on this page are taken from different angles and can be enlarged.

Problems specific to industrial design

― In addition to industrial design, you are also involved in design archives at the museum.

Ueki IDAP is different in form and purpose from the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka's original archive project. It is not a project to collect, organise and store actual materials at the museum, but to collect information and make it available to the public. On the other hand, the original archival materials in the field of design include the materials of Japan's oldest advertising agency, Man-Nen-Sha, which Sugaya mentioned in our previous interview, as well as "PRES ARTO", an advertising distribution magazine published in Kansai from the pre-war period until the 1980s, and the materials owned by its publisher, the Press Alto Society. A team of researchers from Doshisha University is carrying out a comprehensive survey of these materials.

In addition, we are beginning to collaborate with the Faculty of Engineering at Osaka City University in order to promote research into the urban architecture of post-war Kansai. By bringing together the three fields of consumer electronics, advertising and architecture, I hope to be able to provide a bird's eye view of the city and life in post-war Kansai and Osaka.

However, the biggest challenge is that if I continue at the current pace with this huge number of things, the number of things I need to do will only increase and not decrease. I think it's probably the same for all archivists in all fields, but I think it comes down to the fact that we need money, people and space.

― Is it possible for IDAP to work with universities to get students to help?

Ueki Osaka Institute of Technology and other universities cooperate with IDAP, but when it comes to cooperation with students, it is quite difficult because not many people choose historical industrial design as their research theme. Many people who want to become designers are not interested in old products, and design history is even more difficult than art history in the future, so not many people are interested in it. Even if they are interested in design history, it is difficult to get them to pay attention to industrial design from the Showa period, because many of today's students grew up after the era of eco-friendliness and have a bad image of mass production and mass consumption.

However, the people who manage the archives in the companies are not only doing it as their job, but they are also supportive and passionate about the idea of cultural rediscovery, so by the end of 2021, when the museum opens, I will be able to say that I have reached this point and I will do our best to pass it on to the next generation.

Common problems in the archive business

― How many museums have archivists who are experts in archiving?

Ueki There are still very few museums that employ archivists as archivists, but we do have one professional archivist in our museum. The archivist manages the archives for both art and design. In addition, there are four curators, including Sugaya, who specialise in design and who are involved in the organisation and research of design works and archival materials. I believe we are the only museum in Japan with such a team. The future of the archive will involve a wide range of activities, including organisation, management, access to materials and dealing with copyright issues. I It is physically and time-consuming for one archivist to do everything, so I believe that a little more human reinforcement is needed when the museum is open.

― It's a great structure. What are your thoughts on the rapidly growing awareness of the importance of archiving in various industries?

Ueki Perhaps they are in a situation where they have been accumulating and are now approaching the limit of what they can do. Our museum is unusual in that it has been a preparatory room for 30 years, and we have been collecting in the absence of a building and with limited public access.

Our museum is unique in that it has been a Preparation Office for 30 years, and we have been collecting without a building and with limited public access. I think the archivist was considered essential because, before the long-awaited opening of the museum, we had to face anew the challenge of making the accumulated materials available to the public, and the need for organisation increased more rapidly than in other museums.

Also, even if curators and researchers knew that there would be a limit to the amount of research they could do if they only had the works and not the materials around them, it's not an industry with a lot of money, so they were probably too busy trying to keep up with the exhibitions that were coming up. It's very good that there is a growing awareness of the need for archivists, but it doesn't mean that the current problems have been solved.

― Are the archives of foreign museums, such as Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the Victoria and Albert Museum(V&A), richer?

Ueki I'm sure they think it's not good enough, but from our point of view it's an enviable environment for archiving. Both MoMA and the V&A have archives, and they are open to the public. In the field of design, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York has made great strides in archiving in recent years, and the Bauhaus-Archiv Museum in Germany has raised external funds to further develop its archive for the 100th anniversary of the Bauhaus. But I think that the essence of the problem is the same as ours.

― It's a question of money, people and places, or rather money is the biggest problem. If you have the budget, you can get the people and the place.

Ueki I think that's really true. In the absence of an increase in the budget for cultural activities, if we add somewhere, we will eventually have to subtract somewhere. We have to keep thinking and thinking and thinking, and then we have to move on to the next generation and think and think again.

When I first became involved with IDAP, I often wondered if things would have been different if I had started ten years earlier. But on the other hand, there are many things that would have been lost if I had not started. I will probably never reach the ideal I had in mind at the beginning of my career. But I'm glad that I started.

Requests when accepting the archive

― Throughout our coverage so far, we have witnessed the hard work of those who host the archive. In particular, when I saw the situation where a large amount of cardboard boxes with randomly placed materials were brought in, I thought that the donor could alleviate some of the burden by sending the materials in a way that is more in line with the work of the organiser. What is the minimum you would like them to do?

Ueki I would be very grateful if you could separate the different types of documents. For example, in the case of graphic design, it would be much easier if the designer's proofs and instructions could be separated from the printed product.

― Why is it better to separate things rather than projects?

Ueki Even for each project, it's better than nothing, but in the case of graphic design, for example, there's a slight difference in the way the printed material is treated when it's stored, compared to the watercolours and pens that are used. It's true that it's very useful to keep track of each project in chronological order and to know the background of it, but it's easier for us to keep them separated by medium for final storage. Naturally, it would be even better if the boxes were separated by size, as there are certain sizes that need to be stored, but first of all, it would be very helpful if the boxes were separated into printed and non-printed items. I'm sure things are different in other areas of documentation.

Discarding to maintain the archive

― It would be ideal to keep the archive in its original state, but space is limited and sometimes you have to make choices. How do you deal with this?

Ueki I don't make value judgements, but I do make judgements as a matter of archive policy. It depends on the field of work, but in the case of graphic design, I receive everything once, and if there are several copies of the same work, such as proofs, I generally keep only one. The remainder, together with those items which have no obvious documentary value, or which are in such poor condition as to be detrimental to other objects, will have to be returned to their original owners or disposed of with their consent. As for books, I do not accept general books held in public libraries. However, I do keep them if they are unique and different from general reproductions, such as if there is writing by the author in them. Therefore, when you donate a book to us, you must agree to dispose of it in such various circumstances. I can still do IDAP on my own, because the products themselves are stored in the company, but when I accept the actual materials, the responsibility I have to assume is much greater. Therefore, I think that we should think carefully about whether or not we can provide for the materials ourselves before making a decision to accept them. Without storage, organisation and access to the public, it becomes a mere warehouse, not an archive, so I must always think carefully about this, and I think it is the job of the archivist to give us the criteria for thinking carefully.

Directions for archiving in the digital age

― In an age where everything is being replaced by digital, an increasing proportion of future archives and collections will be digital rather than physical. How do you think this will change the way you store things?

Ueki Data is raw, so I keep it in a refrigerator called a server, but it has a shelf life, so it may not be usable in 10 or 20 years. Or the fridge itself may be broken and you may not be able to retrieve it. Our archivists are always talking about how important it is to take care of the data by examining these aspects in a continuous way, but I feel that this awareness is not yet widespread. So I think that when we accept data, we need people who have the expertise to judge what form and what quality we should include.

― What is the global trend?

Ueki The collection of digital content does not seem to be very advanced worldwide. MoMA has also started, but it's a bit slower than the collection of objects, or it's more of a wait-and-see approach. I think at this stage it's very difficult to say what the scale will be in the future and what the burden will be. From a space point of view, the data doesn't take up much space, but I don't know at this stage what the maintenance costs will be.

― When you consider the possibility of having to replace the whole thing in the event of major changes in the future, such as security, hard drive life, recording media or the cloud, it's always a hassle, so it's hard to imagine the final cost.

Ueki That's right. Paper materials, for example, can last for 100 years if you provide the right storage environment. Today's paper is not acidic, so it lasts much longer. So you can leave it for 100 years. With data, you can't see if it's deteriorating, and you can't open it at a moment's notice.

We've also had a number of failures where the hard drive containing the data of the work has broken and won't open, so we have to be careful with digital. In the future, I think we will come back to the question of whether we should hold the data ourselves, whether we should store it in the cloud, and even whether we should think about what a collection is in the first place.

Future prospects for the opening of the museum

― Will you be prioritising the Kansai region for your design collections and archives in the future?

Ueki As for design, as I said earlier, there is no public design museum in Japan, and there is no museum in Japan with four curators specialising in design, so I don't think there is anything special about Kansai. We are always thinking about the significance and meaning of having an art museum in Osaka, and we wonder who will dig up the local assets and culture if we don't dig them up, and who will preserve them if we don't preserve them. However, we don't intend to create a "story about how good Osaka was" by only working on Osaka. We want to show how much of an impact local assets have had, not just in local histories, but with a national or international perspective. In order to do this, I have to work hard to sort out what I still have accumulated. The museum will be open by March 2022 and the full-scale exhibition will start in April, so I will be working diligently towards that goal.

― We look forward to opening the museum in 2022. Thank you for taking the time out of your busy schedule to talk to us.

Enquiry:

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka http://www.nak-osaka.jp

Industrial Design Archives Project http://www.nak-osaka.jp/idap/index.html

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office)

Date: 24 June 2018, 13:00 - 14:30

Location: Preparation Office

Interviewees: Tomio Sugaya (Deputy Director, Research Director, Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka)

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota、Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

Description

Description

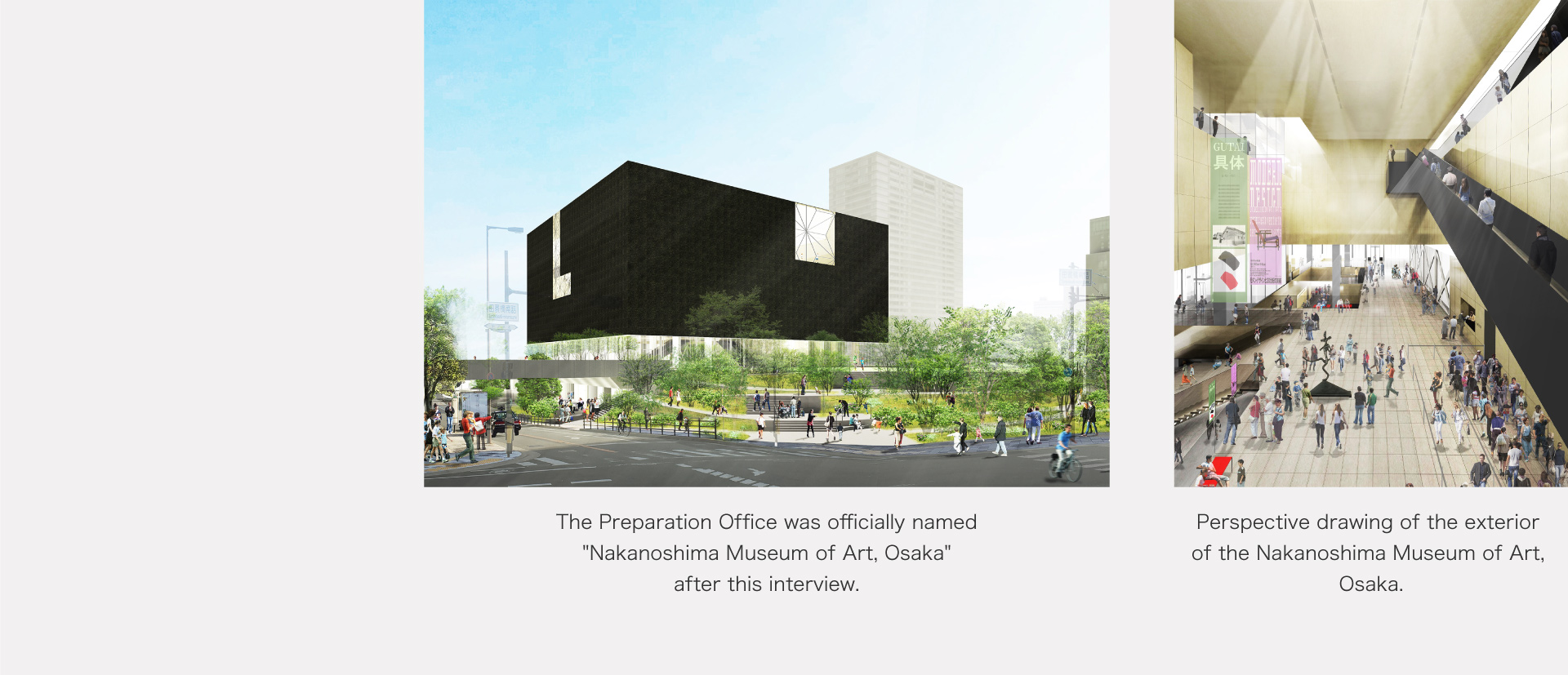

The Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka was first announced in 1988, at the height of Japan's bubble economy, and after 30 years and many changes, it is finally scheduled to open in 2021. Tomio Sugaya, head of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office), has been one of the members of the preparation office since 1992, and has been asking the question "What is the museum of the future? As a member of the preparatory office since 1992, he has been asking the question, "What is the future of the museum?" He has also discovered the field of "design archives", which has yet to take root in Japan, and is laying the foundations for this field of activity.

Some museums already have design collections and archives, such as the National Crafts Museum of the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, the Toyama Prefecture Museum of Art and Design and the Musashino Art University Museum & Library. However, many of them focus on specific themes such as posters, chairs or crafts, or on the work of masters such as Yusaku Kamekura or Sori Yanagi. Of course, these are very valuable archives, but we would like to see something that gives us an overview of design from a larger perspective.

This is because design is a tool and an environment that is closely connected to people's lives, and not a single chair, a single poster or a single car. In other words, design archives are an essential part of the study of society, culture, science and technology. It may not be a work of art, but it is an object that should be preserved as a valuable social archive.

In this context, the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka has four main activities: "special exhibitions", "collection exhibitions", "collaboration" and "archive". I don't know of any other public museum that proudly mentions "collaboration" and "archive", but it seems that these two will be the main focus of the museum's activities. We asked Tomio Sugaya how the activities of a public museum and a design archive are linked, and what kind of structure will be put in place.

Interview

Interview

Future generations will decide the value of the archive.

Outline of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

― I heard that the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka will also focus on design archives. This is a big challenge for you, but first of all, could you give us an overview of the museum?

Sugaya Preparations are underway for the museum's opening in 2021. The site is located in Nakanoshima, in the heart of Osaka City, on a historical site where the warehouse of the Hiroshima clan used to be located in the Edo period. The new museum will be a five-storey building, with no basement, in order to preserve the remains of the building and to protect it from flooding due to its proximity to the Dojima and Yodo Rivers and Osaka Bay. Mr. Katsuhiko Endo was selected for the architectural design in a competition, and the construction is being carried out according to the concept of "a museum like a city where various people and activities intersect".

The management of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office), the Osaka City Museum of Fine Arts, the Osaka Museum of History, the Osaka Museum of Natural History, the Osaka Science Museum and the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, all currently under the jurisdiction of the Osaka Municipal Government, as well as buildings and artworks, will be transferred to an independent administrative corporation to be established next year. From there, the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka will be managed by a private company, which will be responsible for planning and organising the opening, exhibitions and publicity.

― The management structure of a museum is quite complex.

Sugaya In the past, public museums have generally worked within the limits of the budget they were given. However, with the establishment of an independent corporation and the subsequent transfer of management to the private sector, there is a greater degree of freedom in terms of planning and management, and a greater degree of autonomy. It also creates the possibility for a wide range of people, particularly staff, to participate in the project, which will allow us to flexibly implement unique projects and projects in line with the times.

― What are the core collections of the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka?

Sugaya The collection comprises approximately 5,600 works of art, including paintings, sculptures, photographs, prints and designs from the late 19th century to the present day, of which 4,600 have been donated and 1,000 purchased. Among the most important collections that characterise the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka are 60 paintings by the Parisian Western-style painter Yuzo Saeki, works of Western modern art by Modigliani and Brancusi, and some 900 works by Osaka-based artist Jiro Yoshihara and the Gutai Art Association.These are some of the most important collections that characterise the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka. Design includes epochal works from the Arts and Crafts movement of the 19th century to Art Nouveau, the Wiener Werkstätte and the Bauhaus, as well as works by modern design masters such as Wagner, Rietveld, Aalto and Japan's Shiro Kuramata.

Exploring the design archive business

― Could you tell us more about your design archive?

Sugaya The idea for the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka was announced in 1988, and a preparatory office was set up in 1990 to formulate the basic policy of including the field of design. After a number of discussions, the museum decided to add a unique feature to its existing collection: a design archive reflecting the industrial and commercial character of Osaka.

One of them is the home appliances, which represent the design of post-war Japan, especially of the Kansai region. Normally, the collection would be based on the actual products, but in reality, it is almost impossible. The reason is that there are so many different types of home appliances, such as washing machines, refrigerators, rice cookers, wiring devices and lighting fixtures. And even if we limit ourselves to washing machines, for example, there are a large number of them, even if we narrow down the list according to age, technical innovation or epochal design. It is not possible to set up a storage facility for all of them, nor is it possible to maintain them properly.

― So how are you currently working on this?

Sugaya We take two approaches to archiving material, with the help of manufacturers. The first is photographs and documents showing the specifications and detailed specifications of the products, which are then rephotographed in the same way as architectural drawings, including plan and elevation angles. The other is an oral history of the designers who developed the product, interviewing them about the design and social conditions at the time of its development.

In other words, by collecting both the "records" and the "memories" of consumer electronics at the same time, we believe that we can create a more multifaceted design archive.

― It's a huge amount of work, going through the process one by one.

Sugaya We could not do it alone. Fortunately, university professors were also interested and in 2014 we launched the Industrial Design Archives Research Project (IDAP), a tripartite project between industry, academia and government, led by the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka (Preparation Office), Panasonic and Kyoto Institute of Technology. In recent years, we have expanded on this by establishing the Industrial Design Archives Association, which includes Panasonic, SHARP, Zojirushi Mahovin, Osaka Gas, Osaka Institute of Technology and Musashino Art University. Little by little, we feel that the circle of activity is expanding. We will keep you updated on the progress of the archive on our website.

― We are also looking forward to an oral history to the designers.

Sugaya In the 50s and 60s, the idea of design was introduced into product development, and many manufacturers set up design departments and began to employ designers. This is the time of the so-called in-house designer, but the people who were active during this period have already retired. We would like to hear from them about the story of the development of the product and about the design situation at the time, which cannot be measured in documents, so that we can get a multifaceted view of design. This will also be uploaded to the website as soon as it is sorted.

― It's going to be a ground-breaking archive.

Sugaya We still have a long way to go, but we hope to continue. We also hope that projects like this will raise awareness among manufacturers and designers about the preservation of their products and materials.

― You said that it is difficult to store the original items at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, but do you leave that to the manufacturers?

Sugaya That's right. As we work on the archive, we will create a record of what is stored, where and in what condition. By sharing this information with museums, manufacturers, researchers and other interested parties, we will be able to identify objects when we need them. Of course, the cooperation of the manufacturers is a prerequisite. The important thing is not to have one institution do all the archiving work, but to have a system, or platform, to distribute the right people in the right places and to centralise the information.

― What else is there to do with the appliances?

Sugaya In 2012, Suntory Holdings deposited 18,000 items from the Suntory Poster Collection. In 2014, Suntory held the exhibition "Posters of the Belle Epoque" in collaboration with the Kyoto Institute of Technology Museum and Archives.

― When it comes to posters, I was impressed by the exhibition of posters of Yoshio Hayakawa from Osaka, which was held a few years ago.

Sugaya That was held at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, in 2010. Before that, we held a large Hayakawa exhibition in Osaka, organized by our Preparation Office. In fact, there are so many graphic designers from Osaka in that generation. Yoshio Hayakawa, Toshihiro Katayama, Kazumasa Nagai and Hiroshi Awatsuji, who worked in textiles, were all born in Kyoto but started their careers in Osaka before moving to Tokyo. Recently, not only talented designers, but also big companies such as Panasonic and Suntory have moved their advertising and promotional functions to Tokyo, and the planners, designers, photographers, copywriters and other creative people involved have moved with them, and I am worried that the cultural hollowing out of Osaka is accelerating.

― It seems that the Agency for Cultural Affairs is moving to Kyoto, and I wonder about the traditional concentration of creativity in Tokyo.

Sugaya In Japan, media and cultural institutions such as broadcasting, newspapers and publishing are concentrated in Tokyo, but this is not the case in the US, Germany and other countries. I think we need to separate them.

In terms of advertising, in Osaka there was the oldest advertising agency in Japan called "Man-Nen-Sha", founded in 1890. It was the company that created the modern advertising agency business, but it went bankrupt in 1999, partly due to the concentration of the advertising industry in Tokyo. As a result, a huge amount of material was in danger of being lost, but people from the Osaka business community bought it and donated it to the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka because they did not want the history of companies in the Kansai region and the records of the early days of advertising to be lost.

― It's an episode that reminds us of the typical Osaka spirit.

Sugaya Man-Nen-Sha's head office building was located in Osaka City. I went with the trustees to the archives and took away about 200 boxes of commercial films and posters. These include planning documents, CEO's greetings, newspapers from all over Japan and Japanese language newspapers from overseas collected for research purposes, and other valuable materials that provide an insight into the activities of the company and its times. For some time we had been storing them in an abandoned school in Osaka City, but teachers and students at Osaka City University, as well as members of the Osaka Society for the Study of Media Culture and History, stepped forward to help us archive them. We have digitised around 6,000 commercial films, but unfortunately we are not able to make them available to the public at this stage because of the complex copyright issues involved in advertising. However, an overview is available on the Osaka City University website under the name of the " Man-Nen-Sha Collection".

― Is it important that the archive is not only preserved but also made public?

Sugaya We have also received a donation of 200 boxes of materials from the Gutai Art Association, which is based in Osaka and has recently attracted international attention. We are in the process of sorting out the 200 boxes of materials donated by people involved in the Gutai Art Association, which has attracted international attention in recent years. I think it is important to make these valuable materials and works available to the public. An archive is only valuable if it is kept and put to good use.

― By the way, I was wondering if, at the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, the archive does not equal the exhibition?

Sugaya For the museum, the object of the archive is the material, not the work. It becomes a collection. Of course archived material can be exhibited, but it is necessary to prepare for the exhibition of archived material. I believe that there are both approaches: to analyse and study the archive and then to organise an exhibition, or conversely to set up an exhibition and then to organise the archive.

― As a private designer, I heard that you are going to archive the materials of Shiro Kuramata.

Sugaya Yes. Shiro Kuramata is an internationally renowned designer who is recognised as an influential figure in design today. At our museum, which collects design works from the 19th century to the present day, we have several of Kuramata's works in our collection, including " Miss Blanche", and we hope to add more in the future. I know that there are many museums abroad that have his works in their collections. As a world-famous designer born in Japan, we would like to add Shiro Kuramata's drawings, photographs, sketches and other materials to the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka's design archive, and we are currently consulting with his wife Ms. Mieko Kuramata.

― It's a very important activity as the precious materials of individual designers go abroad or are lost.

Sugaya I recently met a Kansai-based architect who told me that he had donated most of the drawings of his masterpiece to the Centre national d'art et de culture Georges Pompidou in Paris. In fact, I heard that many of the drawings of the great post-war architects, including Kenzo Tange, went to Harvard University and Pompidou. Japanese architecture is now attracting attention from all over the world, but researchers have to go to Paris or Boston to see the materials. Even if you can see them digitally or on the internet, you still want to see the original hand-drawn drawings. Kuramata's materials are currently in Ms. Mieko's possession, but considering the importance of the materials and the need to preserve and make them available to the public, we think it would be better to keep them at a public institution in the future. This will provide a basis for future research on Kuramata and, as a result, will enhance the reputation of Shiro Kuramata.

Design archives and the future of museums

― So far we've mainly talked about donations, but do you also buy works and archives?

Sugaya When it comes to art, buying a work of art is becoming increasingly difficult. The best works of art are rarely available on the market and, when they are, they are very expensive. On the other hand, the archiving of donated materials is becoming more and more important. The first thing we will do is to archive the materials we receive.

― The way museums are run is going to change a lot.

Sugaya That's right. At the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, too, we have four guiding principles: organising special and temporary exhibitions, displaying the collection, archiving, and collaboration. In the industrial design archive I mentioned earlier, that is, the archive of household appliances which I mentioned earlier, we are working with manufacturers, universities and people with an interest in art and design to explore the possibilities of developing and using the archive.

I feel that the concept of the museum has changed a lot in the last 30 years or so. In the past, museums tried to have as many staff as possible and do everything on their own, but nowadays they are no longer able to maintain a large organization on a budget. What has emerged is a vision of the museum as a 'platform'. It is an image of a new public facility where diverse people can gather, flow, meet and work together through art and design.

― You already have an archive in place, but will the public be able to access it once the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka opens?

Sugaya Yes, that is our goal. Today, attitudes towards archives are changing dramatically. In the past, it was usual to first catalogue, organise and publish. But nowadays we don't stick to a catalogue, but start with a large group of books by age and item, and then sort them into smaller groups. Then, if people want to look at them, we ask them to look at some of the smaller ones, and we work with their help.

For example, if we are working on the archive of a design exhibition, we would put together a rough outline of all the relevant materials, such as the proposal, the list of exhibits, the exhibition plan, the publication, etc., and then we would improve the accuracy of the archive by involving the visitors. If we try to make it perfect from the beginning, we will never be able to make it available to the public.

― I saw the plans for the Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka, and it has a large archive room.

Sugaya I think I've got a reasonable size. The only problem is the film. Film deteriorates rapidly in normal conditions and requires a special space with low temperature, low humidity and air circulation. In the archives of architecture and design, especially, there is a huge amount of photographs of works. The Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka will therefore have a dedicated storage space for film. Of course, we will also be working on digitisation at the same time.

― What does Mr. Sugaya think is the importance of the Design Archive project?

Sugaya In Japan, design, especially industrial design, is often talked about in terms of industry and economy. However, as we are a museum, we think of design in terms of culture rather than industry. Especially when it comes to the design archives, we don't give equal weight to designs that have won big awards or have been a hit. For example, manufacturers tend to favour products that have won the G-Mark (GOOD DESIGN AWARD), but this does not mean that the reputation of that era will last forever. In thirty years' time, designs buried in the shadow of the G-mark may be re-evaluated. It is important to have a neutral point of view when it comes to the archive business, and what it conveys not only from the past to the present, but also to the future. The archive is a cultural resource for future generations to discover new things.

― Finally, is there anything that you would like to achieve as part of the Design Archive project?

Sugaya It's a spatial archive. I heard that the interior of Shiro Kuramata's sushi restaurant in Shinbashi has been bought by a museum in Hong Kong called M+ and will be recreated. First of all, we are thinking about how we can archive the spaces, shops, bars, restaurants and other commercial spaces created by Kuramata and other designers. For example, many of the interiors of Kuramata and Takashi Sugimoto were designed in collaboration with artists, but at the moment we can only imagine them by looking at photographs. In them, valuable works of art were part of the spatial design.

The bar where Kuramata and Sugimoto worked was also a meeting place for cultural figures and designers of the time, and is an important archive of design memories. There is a movement to preserve architecture, but interior design disappears like smoke before you know it. Even if it is difficult to reproduce the original, we are trying to find a way to create an archive where people can experience the space by using digital images.

― These days we have various visual technologies such as projection mapping, which I would hope to see come to fruition. Listening to you today, I was reminded of the importance of archives.

Sugaya The value of the archive will be determined by future generations. We believe that this is why we have to preserve and pass on as much material as possible in our archive.

― Thank you very much.

Enquiry:

Nakanoshima Museum of Art, Osaka

http://www.city.osaka.lg.jp/keizaisenryaku/page/0000009428.html

Reference:

Industrial Design Archives Project (IDAP)

https://nakka-art.jp

Osaka City University "Man-Nen-Sha Collection".

http://ucrc.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/mannensha/