Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Taku Satoh

Graphic Designer

Date: 13 February 2025, 13:00–15:00

Location: TSDO Inc.

Interviewee: Taku Satoh

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

PROFILE

Profile

Taku Satoh

Graphic Designer

1955 Born in Tokyo

1979 Graduated from the Department of Design, Tokyo University of the Arts

1981 Joined Dentsu Inc. after completing graduate studies at the same university

1984 Established Taku Satoh Design Office

2007 Appointed as one of the Directors of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

2017 Became Director General of 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT

2018 Renamed the office to TSDO Inc.; served as President of the Japan Graphic Designers Association (JAGDA) until 2024; received the Art Encouragement Prize of the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (2018)

2021 Awarded the Medal with Purple Ribbon

2025 President, Kyoto University of the Arts

Description

Description

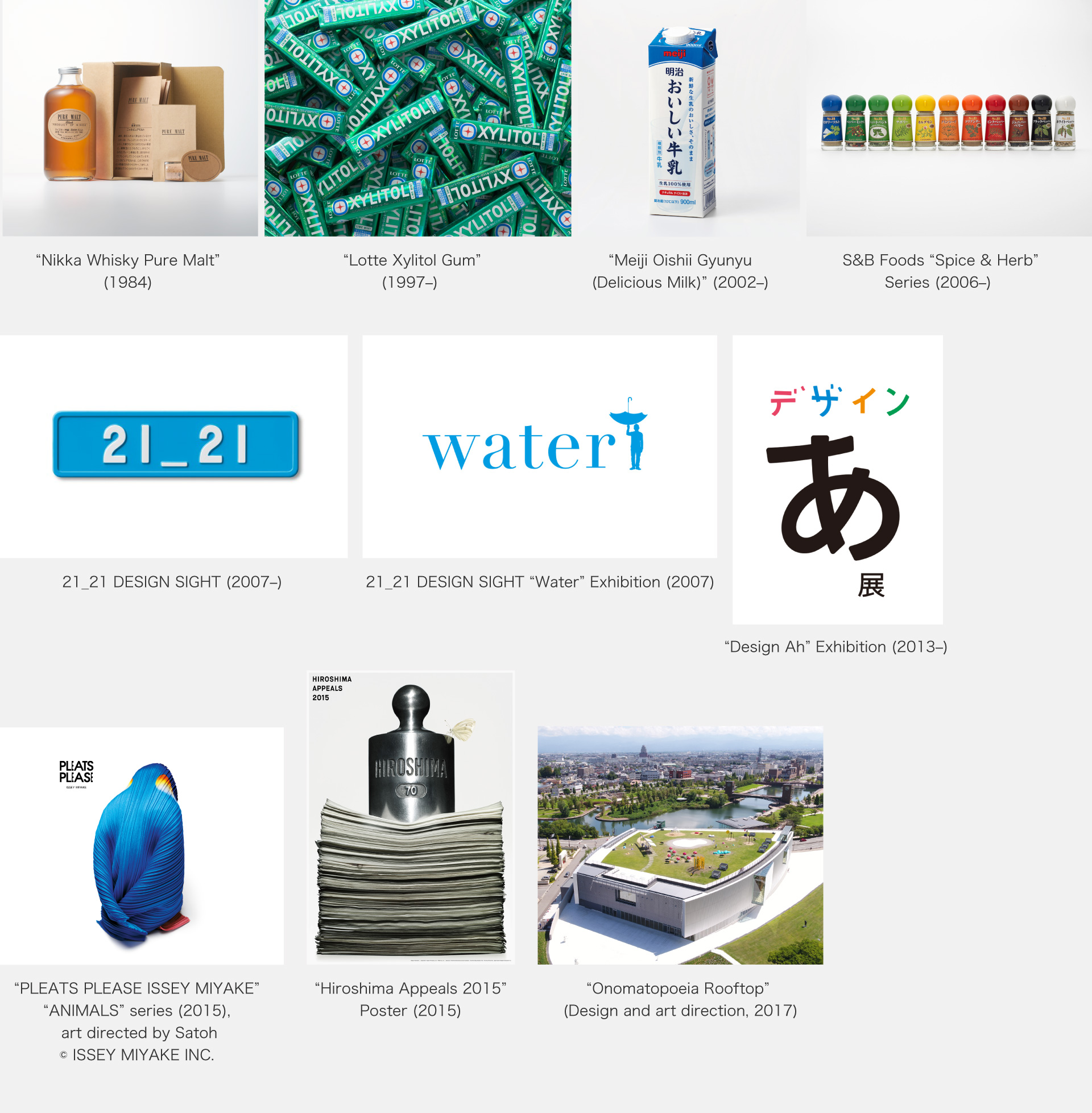

Taku Satoh describes design as “the technique for appropriately connecting things.” His work spans product packaging, branding, exhibition direction, education, and television programme production. Representative works such as “Nikka Whisky Pure Malt,” “Lotte Xylitol Gum,” and “Meiji Oishii Gyunyu (Delicious Milk)” are widely known for designs that blend naturally into everyday life while retaining a distinct presence.

Satoh’s design practice is characterised not only by refined formal skill but also by a deep engagement with the underlying ways of thinking. He likens design to “something like water,” seeing it not as the pursuit of ornament or beauty but as a connective function—allowing objects and people, society and everyday life, to be re‑linked in fluid and meaningful ways. Rather than providing superficial or temporary solutions, his work begins by reconsidering structures and posing fundamental questions. This gives his approach a philosophical depth that transcends the conventional boundaries of graphic design.

These ideas are articulated in his book “Sosuru Shikō” (“Plasticity of Thinking,” 2017, SHINCHOSHA). By applying the concept of plasticity to thought and behaviour, he advocates the ability to adapt to circumstances while maintaining essential qualities. New value is found not by asserting the self but by observing and responding to one’s surroundings—an attitude consistent with his principle of “doing what should be done, rather than simply what one wants to do.”

His contributions to education and public engagement are equally significant. As the overall director for NHK E‑TV’s “Design Ah!” and “Design Ah! neo,” Satoh helped develop programmes that communicate “the perspective of design” in ways accessible even to children. His “Design Anatomy” project thoroughly examined the structure, distribution, labelling, and materials of everyday products, making visible the often‑overlooked mechanisms embedded in daily life. These efforts helped redefine design—once seen as the domain of specialists—as a mode of thinking relevant to everyone.

In 2025, Satoh became President of Kyoto University of the Arts. Having positioned design as “thinking for someone else,” he continues to emphasise observation, inquiry, and transformation as core capacities. His work, which links education and practice, will only grow in relevance in the years ahead.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Packaging Design

“Nikka Whisky Pure Malt” (Product development, 1984), “Taisho Pharmaceutical Zena” (1992), “Lotte Xylitol Gum” (1997–), “Lotte Mint Gum” series (1993–2013), “Calpis” (1993), “Meiji Oishii Gyunyu (Delicious Milk)” (2001–), S&B Foods “Spice & Herb” series (2006–), KIRIN “Namacha” (Kirin Beverage, 2020–2023)

CI/VI (Corporate Identity / Visual Identity)

21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa (Symbol mark, 2004), National Museum of Nature and Science (Symbol mark, 2007), National High School Baseball Championship (Symbol mark, 2015), Cleansui (Corporate identity, 2009–), 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT (Logo and others, 2007–), “PLEATS PLEASE ISSEY MIYAKE” (Graphic design, 2005–)

Product & Spatial Design

“FOMA-P701iD” (NTT DOCOMO, 2005), “Optimus LIFE L-02E” (LG Electronics Japan, 2012), Musashino Art University Museum & Library (Logo, signage, furniture design, 2010–), Okinawa “Soranomori” Clinic (Creative direction, 2014–), Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art and Design, “Onomatopoeia Rooftop” (Design and art direction, 2017)

Media & Educational Projects

NHK E-TV “Nihongo de Asobo” (Let’s Play with Japanese, Art direction, 2003–), NHK E-TV “Design Ah!” and “Design Ah! neo” (Planning and general supervision, 2011–; “Design Ah! Exhibition” 2013, 2018–2021; “Design Ah! Exhibition neo” 2025), “Hoshiimo Gakko” (Dried Sweet Potato School, 2007–)

Exhibition Direction

“Taku Satoh: Design of Everyday Life” (Contemporary Art Gallery, Art Tower Mito, 2006), “water” (21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, 2007), “Design Anatomy” (Matsuya Ginza Gallery and others, 2001–2003, 2016), “Jomonjin” (Prehistoric Jomon People, National Museum of Nature and Science, 2012), “KOME: The Art of Rice” (21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, 2014), “pooploop” (21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, 2024), “The Art of the RAMEN Bowl” (21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, 2025)

Publications and Media Appearances

“The Whales” (DNP Communication Design, 2006), “Designer and Tools” (Bijutsu Shuppan, 2006), “Shaping Thinking” (Shinchosha, 2017), “Design Theory of Mass-Produced Goods” (PHP Shinsho, 2018), “The Book of Marks” (KINOKUNIYA COMPANY, LTD, 2022), “Just Enough Design” (Chronicle Books, 2022)

He has received numerous awards, including the Tokyo ADC Award, the Mainichi Design Award, the Art Encouragement Prize of the Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, and the Medal with Purple Ribbon.

Interview

Interview

Everything I become involved with strikes me as fascinating,

and from that, what I need to do naturally comes into view.

Shifting Form with Ease

ー Mr Satoh, you are one of the key figures who have helped make design accessible to a wide public today. Your book "Sosuru Shikō" (Plasticity of Thinking) is written in an approachable style, allowing general readers to understand the background from which design emerges.

Satoh No, it is simply that I’m not familiar with specialised terminology. Designers often use difficult or technical words, but that has never been my strength—and not having acquired that kind of elevated vocabulary may even have worked to my advantage. At the root of my work is the wish that ordinary people, including children who may not be particularly interested in design, will find it engaging and feel—even a little—“Design is interesting!”

If I hadn’t become a designer, I would probably have found designers and design rather off-putting. I don’t care for didactic design, and I want to remain as ordinary a person as possible myself.

ー In writing books, was there also a sense of wanting to leave a record of yourself—an archival impulse of sorts?

Satoh No, that intention was not present at all. In 2004 I held the exhibition “Taku Satoh: PLASTICITY” at the Ginza Graphic Gallery. As I was writing down the background to the works for that exhibition, an editor who read the text suggested, “Why not turn this into a book?”. That was the beginning. I started writing gradually, and it eventually became "The Whales".

My next book, "Plasticity of Thinking", emerged from numerous evenings spent drinking and chatting with the editor. It was through those conversations that the direction gradually became clear. I was told, “Just write whatever comes to mind first,” and as I kept jotting down the thoughts that occupied me day to day, the book slowly took shape. It took about two years to complete.

ー The title uses the character「塑」(so), associated with modelling and plasticity—kneading clay into form, malleability, the capacity to deform without breaking. Why did you choose this title?

Satoh I had used “PLASTICITY” as the subtitle for my 2004 solo exhibition. Even then, I wished to adopt plasticity as a stance towards society. When I asked myself what design is and what designers do, it became clear that, in my case, it was not about creating a personal style to be applied uniformly. It was about responding afresh each time, adapting to the environment and circumstances at hand. That, to me, was plasticity itself.

ー In addition to "Plasticity of Thinking", your essay “The Campaign to Eradicate ‘Added Value’” was also memorable.

Satoh In fields such as advertising and product development, “added value” used to be excessively emphasised, and the term became omnipresent. People would say, “What matters is added value,” and the expression was used everywhere. Yet consider picking up a pebble on the roadside and using it as a paperweight. That is not the result of someone attaching value to the object: the value lies in one’s relationship with the stone.

Even so, people insisted that value must be “added”. I felt a kind of anger—was not this very way of thinking the problem?

I would write down these thoughts, show them to my editor, and debate them over drinks. We continued this exchange for around two years until the piece was finished.

From an artist’s orientation towards design

ー Your father was a graphic designer. As a child you were good at arts and crafts and PE, and as a junior high school student you listened to rock music and admired album covers. While studying at Tokyo University of the Arts you played in a band as a percussionist. After graduation you joined Dentsu and were assigned to the Nikka Whisky account.

Satoh Perhaps because my father was a designer, I was interested in design from a young age, yet I never tried to pursue it single-mindedly. Somewhere inside I always harboured the feeling that I wanted to become an artist. It became a habit to come home at night and paint. People who enter this world usually wish, at heart, to express themselves.

But through the sense of fulfilment I gained from working on Nikka Whisky, I decided to stop struggling towards becoming an artist. I was able to let go of that.

ー At Nikka you worked on “Pure Malt”. How did you come to be responsible for that?

Satoh It was more than forty years ago, at a time when advertising agencies were not yet involved in product development. One day I told my boss that there was no whisky I actually wanted to drink. He replied, “Then what kind of whisky would you want to drink?”, and that led—very much as a long shot—to my making a presentation to Nikka Whisky.

Of course, because we were talking about a mass-produced product, I could not make a proposal irresponsibly. I visited the factory to study Nikka’s history and techniques, and there I encountered “pure malt” – malt whisky drawn straight from the cask. I proposed that we turn that original whisky, just as it was, into a product for younger drinkers, and designed everything: the bottle, the packaging, the advertising, and the in-store POP materials.

ー It became a huge hit, and its simple design drew a strong response as something completely new.

Satoh The experience of developing Pure Malt was what truly flipped the switch for me in terms of design. I deliberately designed the bottle so that, once used, people could peel off the label and continue using it. But I was not sure whether thinking in that way even fell within the scope of design, so in a sense I tried it as an experiment. When a powerful response came back, I thought, “So, it really is all right to think about such things,” and I became aware of that. My focus shifted decisively towards design and I realised how fascinating it was.

After I left the company and went freelance, Pure Malt came out into the world. That became the catalyst for a stream of package design commissions, and for several years I lived through a whirlwind of work. I was even asked to design lipstick for a cosmetics brand, and agonised over how women actually used it. I knew nothing about anything, and simply threw myself into responding to each job I was given.

ー In 1990 you held your first solo exhibition, “NEO-ORNAMENTALISM”, at AXIS Gallery.

Satoh The media artist Masaki Fujihata and I were classmates from our cram school days, and he helped me put together an experimental series of CG works alongside the packaging projects I had done as commercial work. I wanted people to know, even a little, that there was this kind of design and this kind of designer. Looking back now, though, I realise it became an opportunity to confirm what on earth I myself was actually doing.

You struggle with design every day, and each piece becomes something tangible out in the world. By lining those works up and looking at them, you can view yourself objectively.

Presumptuous as it may have been, I sent an invitation to the exhibition to Yusaku Kamekura, although we had never met. To my astonishment, he came. I got a call from staff at the venue, jumped into a taxi and rushed over. For a youngster like me, Mr Kamekura was a legendary figure in the clouds. I had absolutely no prior connection with him, so I was so nervous I cannot even remember what we talked about, but I was delighted that he had taken an interest.

“NEO-ORNAMENTALISM” poster, AXIS Gallery (1990)

Beyond the conventional boundaries of design

ー When I interviewed Masayoshi Nakajo, he said that in his generation the work was “Please design this package, this wrapping paper,” whereas for your generation and after, including yourself, the work is no longer like that: you go much further into the fundamental planning and development of products, so it is completely different. He also said that rather than putting your own individuality out front, you place more weight on the themes of the company and the product.

Satoh Goodness, no… it is an honour just to have my name mentioned by Mr Nakajo. I worked with him for a long time on the NHK programme “Nihongo de Asobo” (“Let’s Play with Japanese”), and I have always held his work in the highest esteem. I truly respected him.

ー Do you yourself feel there has been a change in what design involves—thinking through the content right down to the inside?

Satoh Very much so. I grew up and became an adult during the period of rapid economic growth. By the time I became aware of things, there were already fridges, televisions and washing machines all around us, and we lived in an age in which you could choose your appliances from a range of almost identical products. It was the arrival of a capitalist society overflowing with goods differentiated only by a thin layer of so-called added value.

People who were born in an earlier time, when there was simply not enough, and who therefore felt real gratitude towards material things, started from a completely different place to us. Our generation is the one that asks, “Why do we need so much of everything?”.

When I was in upper secondary school, photochemical smog began to pollute the air in the cities and environmental issues started to appear in the news. It became a question whether we could go on using resources lavishly, endlessly making things and throwing them away. Unlike the generations for whom everything could still be read in a wholly positive light, we were inevitably pushed back to the question of “in the first place”.

That way of thinking was already a foundation for me when I worked on Nikka Whisky at Dentsu. To my eyes, Nikka seemed to be doing things in a way that chased after Suntory. When I thought about what made Nikka special, it became apparent that it was in the taste of the whisky and in their attitude towards making things.

When I actually went to the production sites, I felt the quality with my own body, and realised that all of that was a kind of asset. I thought that, if we were going to communicate this to the younger generation of the time, we would have no choice but to communicate it through the product itself, not through advertising.

While I was working in advertising, I began to feel that perhaps advertising itself was not where the real issue lay. I think that background also comes from having grown up during the high-growth era.

The question arises: “Is this even necessary?”. I was a cheeky youth who loved rock music, so older generations must have thought, “What is he talking about?”. I have always had a contrarian streak; I cannot help but be bothered by things and ask whether we can really go on like this, why there are so many similar things in the world.

What a designer ought to do

ー Clients who sympathise with that way of thinking ask you to get involved from the very roots, wanting to change things fundamentally. Has such work continued to increase?

Satoh These days I am often invited in from the stage where a project is only just beginning to move. I have more work that involves building things up from scratch. Of course, when you are young you very rarely receive that kind of commission. Usually the contents and the name are already decided and you are asked to design the package.

Sometimes you can go back as far as “in the first place”, and sometimes the scope is more or less fixed and you have to discover what can be done within it. So I chose not to have any fixed way of doing things or personal style at all, and instead to adapt to the situation every time.

Even so, I say what I think honestly. On one project, I was asked to design a product, but the company’s logo seemed regrettable to me; I felt it did not embody the corporate philosophy. The logo would appear on the package, so it would be a major visual element, and I told them that this too ought to be reconsidered. I carefully explained that the corporate logo is the company’s face and extremely important. The person I was talking to, however, was flustered and said, “That would go beyond the scope of my responsibility; I cannot do that,” and in the end the work disappeared.

ー That is an unfortunate outcome.

Satoh They must have judged that they could not work with someone who says such troublesome things. But I still try to convey them honestly. I do not say these things because I want the job; if I do not clearly state what I think is wrong, I cannot be convinced myself as we proceed. The logo is one element of the package. To grit my teeth and use it, or to leave it there and pretend not to see it – I simply cannot turn a blind eye like that. In my younger days my feelings about that were particularly strong.

On the other hand, there have been similar cases where, having pointed out the issues frankly, people have understood, and a small design job at the outset has developed into a project to rethink the entire corporate identity (CI).

ー Your activities are wide-ranging: not only product designs such as “Lotte Xylitol Gum” and “Meiji Oishii Gyunyu (Delicious Milk)”, but also communicating design to children through NHK E-TV’s “Nihongo de Asobo” and “Design Ah!”, and directing exhibitions such as “Design of Everyday Life” at Art Tower Mito (2006). From your point of view, are all of these simply part of your design practice, or are you sending them out with the aim of changing society as a designer? How do you see it?

Satoh There is no dividing line there for me. Each piece of work differs only in whether the initial impetus comes from outside or from myself; all I do is what I ought to do.

There are things I can do, and situations where design skills are needed. I do not know whether I truly possess those skills, but if there is an opportunity to make use of them, I simply do the work. Nothing changes in that sense.

As I mentioned earlier, even when the conditions are such that I can only become involved on certain premises, if I feel there is something that ought to be done, I cannot help going all the way in. When I am asked to develop a product, I find myself becoming interested in what technologies led to that point. I start going to factories and talking to the people in the laboratories. Everything involved begins to seem interesting to me, and within that, what I ought to do gradually comes into view.

In that sense, even work that is externally initiated is at the same time self-initiated; there is no real difference.

Wanting to delight people

ー You express all that as a designer, and in your case that expression has strong impact and communicates powerfully to society. When Meiji first presented the proposed brand name “Oishii Gyunyu” (“Delicious Milk”), you were initially rather perplexed, I understand. Yet by bringing what could easily have provoked a backlash into a clean, decisive design, you managed to create something that people accepted without resistance.

NHK’s “Design Ah!” likewise could easily have turned into something that felt like schoolwork if treated in an overly earnest way, but you made it an enjoyable experience instead. I think that skill is remarkable. Is that something you are conscious of, or something you were simply born with?

Satoh I am not consciously aware of it. If I were, I suspect the outcomes would look different. One never really understands oneself. I have loved making people happy since I was very small. I loved pranks and fun more than study. I was always thinking about mischief. I wanted to make people chuckle, to surprise them a little. Even at primary school, if a friend was feeling down, I would find myself wanting to cheer them up. I naturally want to make people laugh. You do not learn that from anyone, so I do not quite know what it is.

ー That desire to entertain people seems to be at the core of your design.

Satoh It is not something I am consciously aware of, though. With “Lotte Cool Mint Gum”, one of the five penguins is raising its flipper—the second one from the front. That, too, comes from a mischievous impulse.

I have an inner sense of how much of that “good-natured mischief” I can allow into something. I am always probing that. Does this have to be kept strictly serious, or, if it does not, then shall we play with it? I am always feeling out where the line lies. Is this the sort of thing where a level of “3” out of 10 is acceptable, or can we go as far as 6 or 7? I have a kind of internal measure for it.

ー The exhibition “pooploop” at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT is the perfect example. A highly serious theme is expressed through a pitch-perfect title that drew in many visitors. It reminded us that nothing in the world is truly rubbish; everything is a resource.

Satoh Because the theme is serious, if we had given it a serious title and serious design, nobody would have come. The question is how to spark people’s interest. How do you send a message to an unspecified, wide audience in such a way that they want to engage with it?

There I have this “mischief ruler” that I mentioned earlier. Sometimes I do not use it at all, and sometimes I use it just a little.

Not wanting to have a style

Satoh For me, design work is about connecting things – linking them towards a better direction. “pooploop” was like that too: all we can really do is to prepare opportunities for people to think.

On the microscopic level, with a single product we ask how we can approach it: whether there are ways to use fewer resources, for instance, and we think together with manufacturers. There is so much we have to face; making things from now on is going to be difficult. Because I want to do whatever little I can, I would like to present starting points—moments that prompt us to think. In that sense I do not maintain any visible stylistic signature. In fact, I do not want to have one.

ー You may not have a stylistic signature in the form, but I believe you do have a certain style in your thinking. That feels like your individuality.

Satoh I am not consciously aware of that. If individuality is what emerges unavoidably, despite oneself, then perhaps, when others look at my work objectively, they may perceive something that could be called an individuality there.

ー And even as you accumulate experience, you continue to retain a strong sense of curiosity.

Satoh As the NHK programme “Chiko-chan ni Shikarareru!” (“Don’t sleep through life!”) suggests, the world is full of things we think we know but do not actually know at all. I suspect that becoming aware of what we do not know stems from curiosity.

Whether something has come about naturally or through someone’s deliberate intention, there are many things in the world that we simply do not understand. I feel that curiosity is the starting point for everything.

ー You have planned many exhibitions and attracted many visitors to them. I feel you also have a talent for drawing out the appeal of archives in museums and similar institutions.

Satoh I am not sure. In 2012 I proposed and realised the exhibition “Jomon People: The Fusion of Art and Science” at the National Museum of Nature and Science. I had designed the museum’s symbol mark, and at the time I happened to have been deeply moved by a book on the Jomon period by the archaeologist Tatsuo Kobayashi. That led me to visit the museum’s storage.

There were human bones from various periods in boxes, and at one point they said, “These are Jomon people,” and brought out skulls. I had already been very interested in the Jomon period, but seeing those bones, I felt, “So these are the people,” and was literally left speechless. I asked Yoshi hik o Ueda to photograph them, and we put on an exhibition that was almost like a photography show. The subtitle, “The Fusion of Art and Science”, grew out of my questioning of the way art and science are usually separated.

“Jomon People: The Fusion of Art and Science” poster, National Museum of Nature and Science (2012)

© YOSHIHIKO UEDA

The exhibition at the museum was composed solely of two Jomon human skeletons from its collection.

©SATOSHI ASAKAWA

Dissecting things and making them one’s own

Satoh In that exhibition we showed only two Jomon skeletons. The rest consisted solely of photographs and texts by researchers. In a venue like that, it is taken for granted that you will display as many items from the collection as possible. An exhibition constructed from just two skeletons was unprecedented; people said it was the first time in the history of the National Museum of Nature and Science.

In other words, you can build an exhibition around a single item. For instance, one painting by Renoir would be enough. You can analyse it from many different perspectives. As long as there is a single object, an exhibition is possible. I feel that if you draw out information from various angles, you can bring to the surface data that nobody had noticed before.

If you can then think about how to visualise that information and turn it into an experience, you may be able to do things nobody has ever done. Once I began “dissecting” things in that way, I felt a boundless sense of possibility.

ー So it is not simply about lining up large numbers of works. That is precisely where design comes in.

Satoh Exactly. It is about drawing out what has not yet been brought to light and making it visible. I use that same analytical method when preparing exhibitions. For example, with the chewing gum I had worked on, all I had designed was the surface graphics. There were many people involved before that stage, and my design sat like a thin membrane on top of their work.

I wanted people to understand that I was not the only one designing it, and that led to the “Design Anatomy” exhibitions (a series beginning with “Design Anatomy = Lotte Xylitol Gum” in 2001, followed by “Design Anatomy = Fujifilm ‘Utsurundesu’” in 2002, “Design Anatomy = Takara ‘Licca-chan’” in 2002, and “Design Anatomy = Meiji Milk ‘Oishii Gyunyu’” in 2003, and later “Design Anatomy: A method for seeing the world through familiar objects” at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT in 2016).

When I met the chewing-gum researchers, they told me one fascinating thing after another that nobody knew. I became so absorbed that it no longer felt right to rely on celebrities in advertising. I felt that if we shared this information, people would gain a much clearer understanding of the product, and be moved by the invisible stories embedded within it. The more interesting it became, the more it amplified the product’s appeal.

Eventually I came to feel that there is not a single thing in the world that is inherently uninteresting.

The “Design Dissection” series was held consecutively: “Design Dissection = Lotte Xylitol Gum” (2001), “Design Dissection = Fujifilm QuickSnap” (2002), “Design Dissection = Takara Licca-chan” (photography, 2002), and “Design Dissection = Meiji Oishii Gyunyu (Delicious Milk)” (2003).

©Ayumu Okubo

ー How, then, are your own works and archives being managed?

Satoh They are in storage, but I am very aware that I must now seriously think about them. There are the works themselves, photographs, drawings, and a large number of constructions we paid to have made for exhibitions – all sleeping away in the warehouse. There are so many that it is almost laughable.

ー It would be ideal if they could be donated or housed somewhere.

Satoh Near the Iwami Ginzan Silver Mine in Shimane Prefecture there is a huge former factory building, and I once suggested that we turn it into the Shimane Design Museum, including my own archives. It seems difficult to realise, though.

ー Do you file the materials for each project?

Satoh I have asked my staff to keep the data, but truly organising it properly would require additional manpower.

ー Have you considered producing a monograph of your work?

Satoh Even if you compile something as a summation at a given point in time and talk about it, by the next day it is already out of date. The very latest things will not appear in it. So I cannot escape the feeling that a monograph is not really necessary.

That said, I do think it would be good to have something tangible in some form. I also work on regional projects, and I keenly feel that if you do not talk about such activities properly, they do not get communicated.

ー You have been involved in “Hoshiimo Gakko” (Dried Sweet Potato School), a project to revitalise the dried-sweet-potato culture in Ibaraki Prefecture; in building the brand for “Ma-ana Mikan” in Ehime Prefecture; in the “Ceramic Valley” project for Mino ware in Gifu Prefecture; in recovery support for the seafood company Kono yo Ishinomaki Suisan in Miyagi Prefecture; and in supporting archiving activities in the Iwami Ginzan region you just mentioned.

Satoh Those activities have become almost impossible to keep track of, so I know that I ought to bring them together somehow as well. But a monograph feels a little embarrassing; I feel shy about looking back over my activities. There is some resistance there.

“Hoshiimo Gakko” (Dried Sweet Potato School), LLP Hoshiimo Gakko (2007–). A book and packets of dried sweet potato were combined in a single package to prompt a re-evaluation of local resources.

“Ceramic Valley” logo, Ceramic Valley Council (2017). The eastern Mino region of Gifu Prefecture (Tajimi, Toki, Mizunami and Kani), known for Mino ware, was named “Ceramic Valley”. Satoh participated as a leader in branding and in considering the area’s industrial development, also designing the logo.

ー Design is going through an important turning point, and I believe your archives and a monograph of your work ought to be preserved.

Satoh I am grateful you would say so. I have designed an enormous number of packages, and I keep at least one box of each. Yet manufacturers produce hundreds of millions of units a year, and once something falls off the production line, not a single one may remain. Consumable items cannot be obtained even if you are willing to pay for them.

If I were to talk about each one, there would be no end of things to say, because each contains a form in which our intentions have taken shape. But if I spend time looking back at my past, I have other things I would rather be doing, so I have not been able to attend to it.

Still, receiving this interview was good timing; it has made me want to think about what I ought to do with my archives.

Thoughts on a design museum

ー There has been debate about whether Japan should build a design museum. What is your view?

Satoh We are now in an age in which anything shaped by human involvement can be regarded as design. If we were to build a design museum, I think there would be real value in communicating to the world the particular philosophy of design that has developed in Japan and the things that emerge from it. I am convinced that this is something we ought to do.

If each country has its own design museum, then this country, too, should have one. At that point, however, the question arises: is it enough to focus solely on modern design, on roughly the last hundred years? Should a design museum really only address that period?

Tools already existed in the Jomon and Palaeolithic periods. The idea of replaceable blades, for instance, has been discovered in the Palaeolithic. That is design. The system of replacing only the chipped part of a blade was already there.

How to position such things historically is one of the issues. But I think we have to make clear how the concepts of design that developed on this soil, when Western ideas of design entered Japan, were transformed. That needs to be visible.

ー So what you have in mind is quite different from a museum that simply collects masterpieces of design.

Satoh Depending on how we define design, the very form a museum ought to take will change. Modern design has only a history of a little over a hundred years. Is that alone enough?

If we go further back, in the Edo period there were systems for recycling resources, and those systems as a whole can be regarded, in a broad sense, as design. People at the time did not think of them as design, but now we can.

Even so, is it acceptable simply to place a famous chair in the gallery and leave it at that? Are we not still stuck in a twentieth-century model of the design museum? Is there not a need for experiential, interactive elements?

The design of the design museum itself must be updated to reflect new ways of thinking for a new era, and must evolve. Devices become obsolete quickly; we take it for granted that they will need to be updated. I feel that the design of the design museum is precisely what must be updated and evolved.

You can even regard the country of Japan itself as a magnificent piece of design. The entire nation can be seen as one large design museum. Yet there is not a single politician capable of thinking in that way.

You can even regard the country of Japan itself as a magnificent piece of design. The entire nation can be seen as one large design museum. Yet there is not a single politician capable of thinking in that way.

ー In such an uncertain era, building a large institution is a risk.

Satoh It is true that unforeseeable events could unfold. Yet without public voice, nothing moves forward. Therefore, fostering greater design awareness among citizens is paramount. Since design permeates every aspect of life, I believe society will gradually shift towards recognising that possessing a design mindset is inherently beneficial, regardless of profession or lifestyle. This conviction led me to launch NHK’s “Design Ah” programme fourteen years ago.

ー You approached the producers saying you wanted to make a programme that communicated the ways of thinking inherent in design. Once it aired, it attracted passionate fans from children to adults. It has become exhibitions and school teaching materials, it remains hugely popular, and is used in many different contexts.

Satoh When we first took the exhibition plan to NHK, they were hesitant. But in the end people queued to get in.

My hope was that the children who watched that programme when they were small—and absorbed the idea that “design is everywhere”—would grow up and eventually find themselves in positions where they make decisions. If even a small number of such people begin to make judgements with a design-oriented mindset, then society itself will gradually change. That was the thought behind it.

ー In April 2025 you became President of Kyoto University of the Arts. Could you share your aspirations for the future?

Satoh I continue my work in Tokyo while travelling to Kyoto about twice a month. Kyoto as a whole feels like an archive of culture, does it not? I think it is meaningful to consider education in a place like that.

Rather than supplying answers, I am the type who prefers to work with students to discover the questions. I hope to build relationships appropriate to each situation through dialogue.

ー One final question. AI is advancing, and we are entering an era in which technology is touching even the very core of human creativity. In such a time, how do you see the work of the designer?

Satoh I am asked that often. I see design as the act of connecting things, so however times may change, connections—“in-between spaces”—will always exist everywhere. AI’s advance cannot be stopped, but the nature of those in-between spaces will change. They are like relationships, and there will be countless tasks involved in re-adjusting them.

There is also the possibility that we will be deceived by AI, so we will need a much sharper ability to discern what is happening. How we cultivate that capacity and that basic groundedness of judgement will become a new challenge.

ー In your writing you speak of the importance of “bodily sensibility”.

Satoh AI is pushing us towards using our bodies as little as possible. If that continues, what will happen to us as human beings? Our bodily capacities will clearly decline. When that happens, we will be forced back to the fundamental question of what it means to be human.

This becomes painfully evident in times of disaster or great hardship. In future, I think our bodily abilities—the capacities necessary simply to stay alive—will be put to the test. AI will not train those for us. So I believe things will become tougher, and we must assume that. We will have to train both our bodies and our minds.

ー Thank you very much for such a fascinating conversation.

Enquiry:

TSDO Inc.