Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Reiko Sudo

Textile designer

Date: 17 June 2024, 10:30-13:00

Location: NUNO (AXIS building)

Interviewee: Reiko Sudo

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

PROFILE

Profile

Reiko Sudo

Textile designer

1953 Born in Ishioka City, Ibaraki Prefecture

1971 Graduated from Tsuchiura Daini High School, Ibaraki

1975 Completed the Department of Crafts and Industrial Design at Musashino Art University Junior College of Art and Design

1983 Participates in the establishment of the textile manufacturer Nuno Co.

1984 Opens NUNO's main shop in the Roppongi AXIS Building

1987 Appointed representative and director of NUNO

1988 Part-time lecturer at Musashino Art University (-2007)

1993 Established the Nuno Research Institute in Kiryu City, Gunma Prefecture

2002 Specially-appointed professor at Tokyo Zokei University (-2007)

2004 Honorary Master's degree, UCA University of the Arts

2007 Professor, Department of Design, Faculty of Design, Tokyo Zokei University (-2019), Professor Emeritus (2019-)

2016 Advisory Board, Ryohin Keikaku Co.

Visiting Professor, Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London

2019 Visiting Professor, Kanazawa College of Art (-2022), Honorary Visiting Professor (2022-)

2022 Visiting Professor, Tama Art University

Major awards

Roscoe Prize (Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, 1994); 2006 Mainichi Design Award (2007) ; Enku Grand Prize (2022) ; 2023 Art Encouragement Prize, Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Art Division, 2023)

Permanent collections

Victoria and Albert Museum; Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Metropolitan Museum of Art; National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, etc.

Description

Description

Reiko Ando has visualised the limitless possibilities of textiles. With the diverse ‘fabrics’ she has created, she has shown that textiles are not just there to assist in the design of clothing and interiors, but that they can also stimulate and extend creativity in fashion and spatial design. The results were demonstrated in the exhibition "Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles" at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, or in Toyo Ito's Sendai Mediatheque, where created a wall with two layers of organza curtains in glass, she is also known for her work at Mandarin Oriental, Tokyo (2005), where she designed everything from the entrance to the reception lobby and 179 guest rooms, including furniture, floors and walls, on the theme of ‘forest and water’.

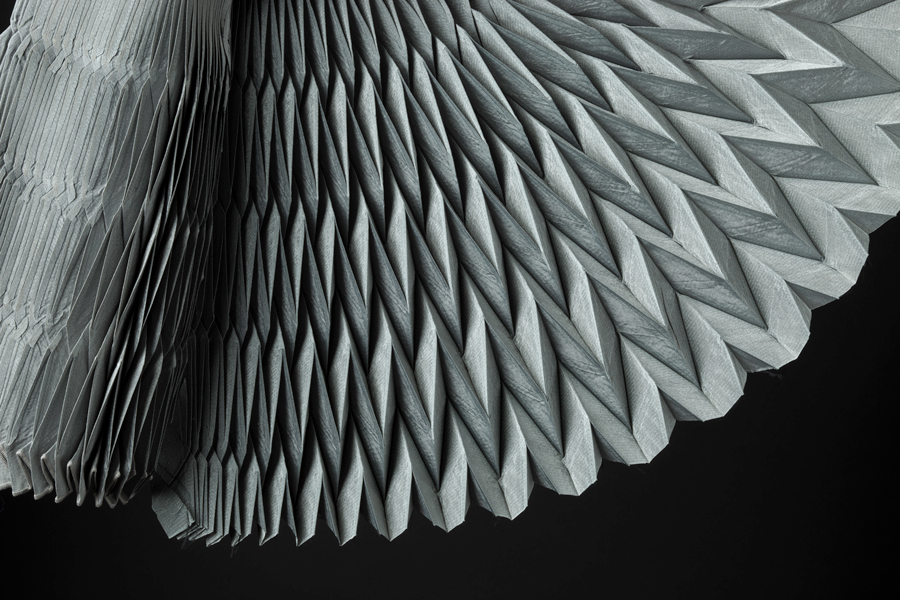

She grew up in a small country town, where the one thing she looked forward to as a child was a visit from a retail peddler. She used to hide behind the adults and admire the kimono fabrics laid out on the tatami mat. From there, she studied Japanese painting with the aim of becoming a yuzen artist, but her interest eventually shifted to textiles. The plain weave technique of tsuzuri weaving, in which the warp threads are wrapped around the weft threads using a sawed-off toe, requires precise work and only a few centimetres can be woven in a day. She began her career as a weaver after learning tsuzuri weaving, but met Junichi Arai and joined NUNO from its start-up period. She expanded her activities to include textile development in general, rather than weaving herself. While in the UK with Arai, she learnt that in Europe, unlike in Japan, hand-weaving of crafts was linked to factory production, and began to study weaving charts. In 1987, she became the head of NUNO. Her deep study of Japanese painting, spelling and weaving and historiography from time to time has formed the basis of her work. She has also explored everything from traditional dyeing and weaving techniques to modern advanced technology, and has introduced unique textiles such as origami pleats, multiple weaving of jacquard cotton with no reverse or front, and felt cloth using needle punch techniques. So far, the company has collaborated with 115 dyeing and weaving factories in 26 production areas across Japan to create more than 3,700 textiles from original designs. Her work has been highly acclaimed both nationally and internationally.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

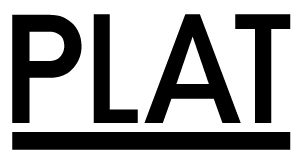

Textiles

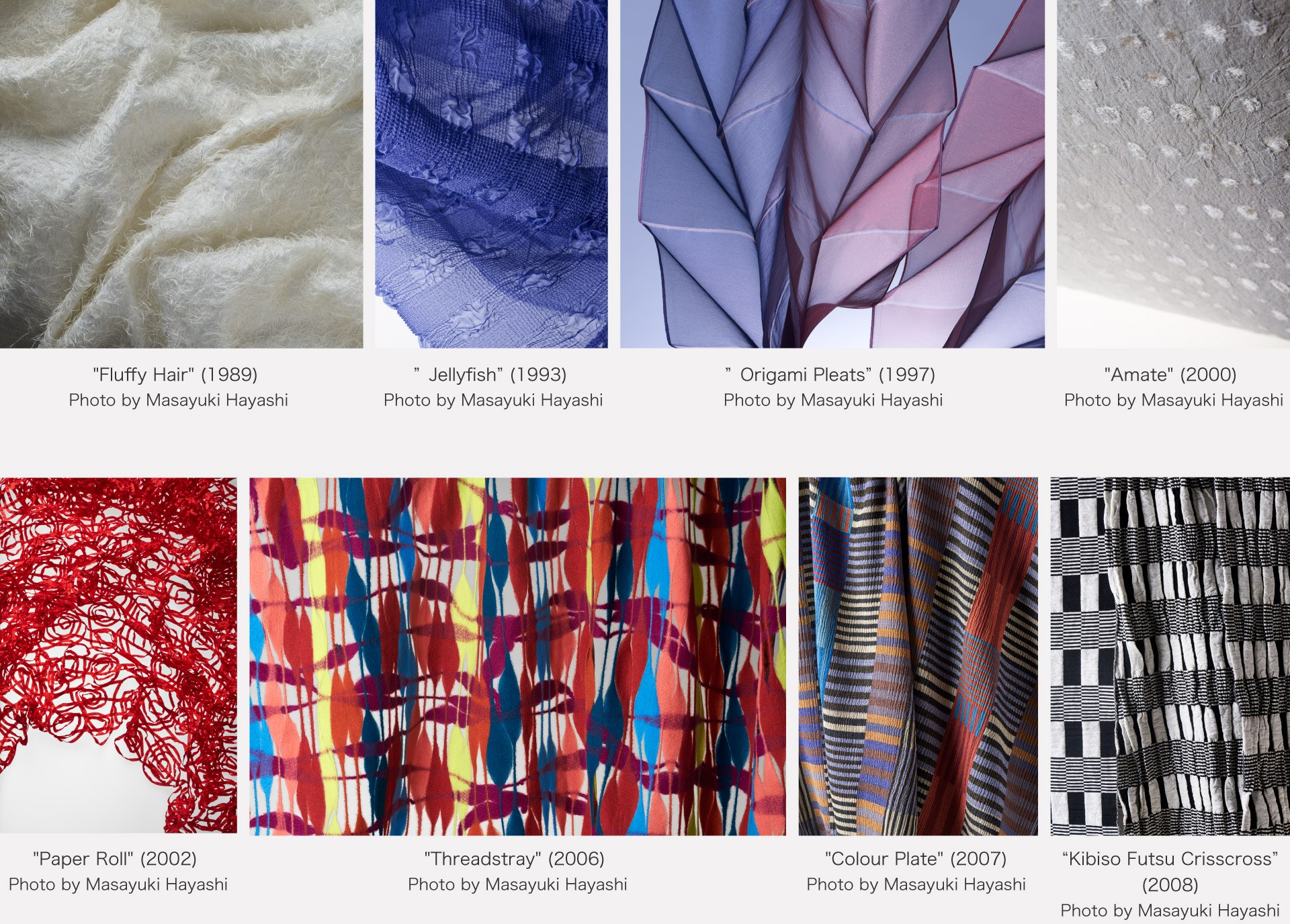

"Bashofu 80 Stripes" (1984), "Fluffy Hair"(1989), sue"Jellyfish" (1993), "Scrapyard Iron Plates" (1994), "Origami Pleats" (1997), "Amate" (2000), "Paper Roll" (2002), "Tiggy" (2003), "NunoTsunagi" (2004), "Threadstray" (2006), “Basketweave” (2007), “Colour plates” (2007), “Swing Squares” (2008), “Kibiso Futsu Crisscross” (2008), “Form” (2009), “Watchspring” (2009), “Polygami” (2010), “Snowy Branche” (2012), “Skylights” (2012), "Kibiso Not-knots" (2013), "Kamaboko Stripe” (2014), ”Trap Circle” (2015), ”Ogarami-choshi Panel" (2015), "Woodchips" (2017), "Motoi" (2022)

Architectural projects

Restaurant Bar "Nomad", Toyo Ito & Associates (1896); Sendai Mediatheque, Toyo Ito & Associates (2000); Matsumoto Performing Art Centre, Toyo Ito & Associates (2004); Mandarin Oriental, Tokyo, Interior design Lim + Teo Wilkes Design Works (2006); Tama Art University Library (Hachioji Campus), Toyo Ito & Associates (2007); TORAYA TOKYO, Naito Architects & Associates (2012); Oita Prefectural Art Museum, Eurasia Garden "Watershed Weeds", Shigeru Ban Architects (2015)

Main solo exhibitions

"Nuno - Sense and Skill", Kyoto Art Center (2001, and other tours); "21 : 21 - The Textile Vision of Reiko Sudo and Nuno", James Hockey & Foyer Galleries, Farnham, Surrey, UK (2005, and other tours); "Japan!: culture + hyperculture", John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington D.C., USA (2008); “Do You Nuno? Reiko Sudo and the World of NUNO”, Matsuya Ginza Design Gallery 1953, Tokyo (2013); "Fantasy in Japan Blue", John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington D.C., USA (2017); "Koinopori Now! Installation by Reiko Sudo, Adrien Gardère and Seiichi Saito", The National Art Center, Tokyo (2018); “Nuno Textiles trace the SilkRoad", Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, Academy, Dunhuang, China (2018); “NUNO: The Prética têxtil contemporânea", JAPAN HOUSE São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil (2019); "Sudo Reiko: Making Nuno Textiles" CHAT (Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile, Hong Kong (2019); “MAKING NUNO: Japanese Textile Innovation from Sudō Reiko” Japan House London, UK (2021, and other tours); 'nuno nuno publication show for "NUNO : Visionary Japanese Textiles"' AXIS Gallery, Tokyo (2021, and other tours); "Circular Design - Kibiso Continues -" Matsugaoka Reclamation Site,Silkworm-Raising Room 2F, Tsuruoka (2021)

Main group exhibitions

"Color, Light, Surface: Contemporary Fabrics", Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, USA (1990, and elsewhere); “Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles”, Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA (1998, and elsewhere); "Contemporary Textiles- Weaving and Dyeing: Ways of Formative Thinking" National Crafts Museum, The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (2001); "Product Design Today: Creating 'Made in Japan'", The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo (2013); "Scraps: Fashion, Textiles, and Creative Reuse", Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York ,USA (2016, and elsewhere); “Encyclopedia of Crafts in Ibaraki Ⅲ Volume on Dyeing" Ibaraki Ceramic Art Museum, Kasama (2018); “DESIGN MUSEUM JAPAN: Collecting and Connecting Japanese Design”, The National Art Center, Tokyo (2022, and other tours); "11th Enku Grand Award Exhibition" The Museum of Fine Arts, Gifu (2023); “Pokémon x Kogei Playful Encounters of Pokémon anc Japanese Craft" National Crafts Museum, Kanazawa (2023, and other tours)

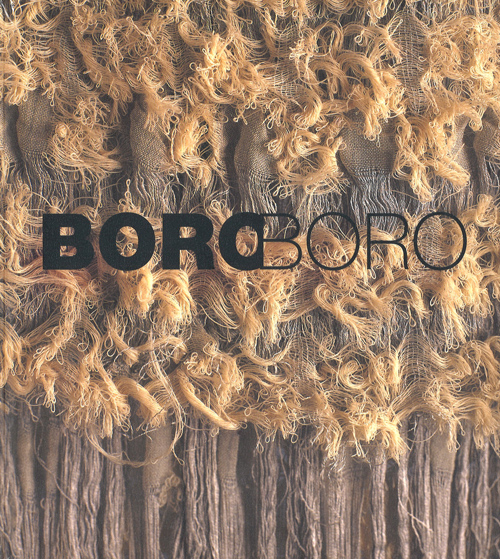

Books

"NUNO NUNO BOOKS : BOROBORO", Nuno Corporation (1997); “NUNO NUNO BOOKS : SUKESUKE” , Nuno Corporation (1997), “NUNO NUNO BOOKS:FUWAFUWA" Nuno Corporation (1998); “NUNO NUNO BOOKS : SHIMIJIMI” Nuno Corporation (1998); “NUNO NUNO BOOKS : KIRAKIRA" Nuno Corporation (1999); “NUNO NUNO BOOKS: ZAWAZAWA" Nuno Corporation ( 1999); " Woods and Water", Mandarin Oriental, Tokyo (2006, not for sale); "NUNO NUNO BOOKS: Zoku Zoku" Ruthin Craft Centre (2012); "Japanese Textiles 1-4 (MUJI BOOKS)" Ryohin Keikaku (2018- 2019); "NUNO - Visionary Japanese Textiles" Thames & Hudson (2021); "Sudo Reiko: Making NUNO Textiles" Books Ogaki (2023)

Interview

Interview

Design is not a one-man job, but something that is created together with various professions

When the world changes, you need an archive.

ー We have known you, Ms Sudo since 1984, when NUNO opened here in the AXIS building, and today we would like to ask you again about your footsteps and the source of your creativity.

Recently, a major exhibition of your work has been held, and we have been able to see a variety of archives, including photographs of your diverse work and production sites, as well as photographs that capture the expression of your textiles, almost all of which are stored at Nuno Co. It's a wonderful archive, and the "nuno nuno" exhibition held at the AXIS Gallery in 2021 is still fresh in our minds.

Sudo In fact, it was an independently organised exhibition. At the time, the AXIS Gallery's exhibition activities had long been suspended due to the coronavirus pandemic, the flow of people had stopped and the building was deserted. When all of Japan was quiet, the Hokuriku region decided to hold the "Hokuriku Crafts Festival GO FOR KOGEI" as a countermeasure against infection. We were asked to do a textile installation in the precincts and corridors of one of the exhibition venues, the Shoukouji temple in Takaoka, Toyama, and while preparing for the exhibition with four members of NUNO, we thought: ‘What we need now that we are sinking in the Corona disaster is artistic communication'. We thought, 'We have to do something’, so we took the plunge and called the AXIS Gallery and asked them if they would like to organise an exhibition.

"nuno nuno" exhibition held at AXIS Gallery to celebrate the publication of "NUNO - Visionary Japanese Textiles".

Photo by Masayuki Hayashi

ー So this was a your-led project?

Sudo It costs money to produce the exhibition. We managed to make it work and hold the exhibition. The budget was limited, but I wanted to do something new, so I asked we+, a contemporary design studio whose activities are based on research and experimentation, to create an installation.

ー Did you have any contact with them before that?

Sudo I was interested in their work, such as the ”MOMENTum” piece they presented at Milan Design Week in 2014, in which water runs over a table. A long time ago, I went to see the exhibition when it was held in Tokyo, and Toshiya Hayashi was there and we had a direct conversation. Our textile installations have always been based on the idea of what you feel in a ‘place’, but unlike that, Hayashi's method of researching and designing is logical and gives a new perspective, which I found very interesting.

In fact, this exhibition was triggered by the publication of a book by Thames and Hudson (hereafter T&H) in the UK, which compiled the fabric-making work we have produced in Japan. Looking back, when we at NUNO celebrated our tenth year since we started, we began to think that it would be important to archive the cloth we had designed from now on.

ー 1994. In the early 90s, when the bubble burst and the world was beginning to change.

Sudo Yes, since the beginning of the 1990s, the number of textiles that could no longer be made has gradually increased. Some factories went bankrupt due to the recession and labour shortages, and some dyes and materials could no longer be used because of their environmental impact. It was not until 2000 that a major shift took place, but change had begun.

That's when I started getting Sue McNab, an Australian photographer, to take down my work. I felt that the texture of the fabric through her viewfinder took it to a different dimension to what I was making, and I thought that one day I would make a book with Sue's photographs. In 1998, she began publishing a book called "NUNO NUNO BOOKS", using seven onomatopoeic words as keywords, such as "NUNO NUNO BOOKS : BOROBORO", "NUNO NUNO BOOKS : SUKESUKE", "NUNO NUNO BOOKS : FUWAFUWA", "NUNO NUNO BOOKS : ZAWAZAWA". We make textiles, but we asked people from other genres - archaeologist Richard Hodges, architect Toyo Ito, novelist Haruki Murakami, musician Art Lindsay and others - to write essays about these mimetic words, which emanate from here like a musical session.

Cover of the ”NUNO NUNO BOOKS" series.

“Swing Squares”(2008)Photo by Sue McNab

“Polygami”(2010) Photo by Sue McNab

ー It's a series of seven books. The textures of the textiles conveyed through the photographs are impressive.

Sudo After we published this series, the director of T&H told me that it was so good that they wanted me to publish it in one volume with their publishers, which came to fruition in spring 2019, but I didn't want to make the same thing again.

I used to go to Central Saint Martins (a college at University of the Arts London) once a year to London for lectures and critiques. When I was there, I met with the editor-in-chief to discuss what kind of book I wanted to make. It had been more than ten years since the publication of the "NUNO NUNO BOOKS" series. We wanted to add some new textiles, so we recklessly proposed that we publish the book as a ‘shoot-along’. Now, what about the photographer and the essays to be published in the book? So we asked Mr Ito, Mr Murakami and Mr Lindsay to republish the essays, and asked Akane Teshigahara, the head of the Sogetsu school of ikebana, and others to write new essays.

As for the photographer, we really wanted to commission Masayuki Hayashi, whose work ranges from artwork to the still life of products and furniture.

ー You didn't just leave the "NUNO NUNO BOOKS" series as they were, but started anew. Why did you choose Mr Hayashi?

Sudo I wanted to have Mr Hayashi photograph products from his point of view. Sue is emotional, while Hayashi is more of a prodding kind of person. I got a willing consent from the busy Mr Hayashi and was going to start filming around January 2020, but it turned out to be a pandemic. But Mr Hayashi also had to cancel his location shoots, so over the course of a year, I ended up with around 600 items to shoot. Every week, I visited Hayashi's studio carrying fabrics to check the textiles and attend the shoots. Mr Hayashi's ability to concentrate and get right into it was amazing.

ー What was the change of mindset from emotional to static?

Sudo Textiles change depending on who uses them. That's why I wanted to see different expressions. That's how the new book "NUNO - Visionary Japanese Textiles" was completed in 2021, and the exhibition at the AXIS Gallery celebrated the publication of the book. It is an exhibition in which Hayashi's photographs and our textiles are shown at the same time. The exhibition also toured to Kyoto as the "KYOTO nuno nuno" exhibition.

Debut as a spelling and weaving artist

ー Ms Sudo's textiles can be seen as an activity to preserve in form the valuable work of production areas and craftspeople that would otherwise disappear. Are you conscious of preserving cultural values?

Sudo I am often told that, and perhaps you would like me to answer that, but I myself am not conscious of it. This is because the production of textiles for industrial products is, without doubt, closely linked to the production area. Without the production area, textiles would never see the light of day.

Through this work, I have learnt that design cannot be done by a single person, but is something that is created together with people from various professions. Japanese textiles have their own strengths and weaknesses, and are characterised by different areas. In the first place, there was the kimono industry, which had a thorough division of labour system in which a group of professionals, called craftsmen, worked together to create one thing for each of the various processes. There was a history of this. Designing textiles in Japan is not possible without connecting with such people, and this is something that is naturally linked to the textile industry. In order to create something, you have to work together with the people in the production area to complete the textile.

ー When did you start aiming for the world of textiles?

Sudo I originally wanted to be a yuzen artist. This is a traditional dyeing method for kimono. From around high school, I was taught painting by Tsunetake Kobayashi in my hometown of Ibaraki, in order to become a yuzen artist. I remember that Mr Kobayashi told me that I had to be able to draw flowers even when I was sleeping. But when I took the university entrance exam, I couldn't get into the department I wanted. So I entered the Junior College of Musashino Art University. At that time, Musashino Junior College of Art had a crafts design department. Professor Seigo (Shogen) Hirokawa, known for his wax-dyeing, taught at the junior college. However, the year I entered the college, Mr Hirokawa moved to Tokyo Gakugei University. The curriculum was not for learning traditional dyeing techniques. So, while attending junior college, I spent my summer holidays studying Japanese painting techniques with Mr Kobayashi, but gradually became more interested in weaving than dyeing, so I did not graduate from junior college but went on to a major course and then worked as an assistant at the university. At the same time, he went to the Kawashima Textile School, which was opened by Kawashima Textile in Kyoto in 1973, where for two months he learnt a technique called tsume-tsuzure, which is a weaving technique in which the weft threads are woven by scraping them together with long, outstretched toes. I stayed in the workshop from 8am to 10pm, weaving silently.

I was elated that I could now become a weaver because I had mastered spelling and weaving. However, when it came time to start working as an artist, I could not eat, as I only received one tapestry order a year from an architect friend. So I earned my income by undertaking work as a ‘draughtsman’, drawing textile designs for bedding based on original drawings of seasonal flowers received from a Japanese painting company in Kyoto. There were no photocopiers back then, so I had to enlarge and copy from the original drawings in proportion. I also did print design work for textiles by Chiyo Uno and Hanae Mori. It was during these days that I met Junichi Arai.

Mr Arai had won the Mainichi Fashion Grand Prix Special Award in 1983, and an exhibition was being held to commemorate the award. I happened to pass by a gallery in Toranomon, where many of Mr Arai's textiles were on display, and he was there himself. As we were talking about various things, he suddenly said, ‘Can you help me?’ and I was invited to stand in a shop selling textiles conceived by Mr Arai. I didn't take it seriously at the time, but later on, friends and acquaintances kept telling me that Junichi Arai was looking for people, and I decided to take part in the launch of NUNO. The handloom was folded and sent back to my parents' house.

It's not enough to just draw superficial pictures

ー What kind of work did you start with?

Sudo I only had skills in spelling and basic weaving structures. I couldn't draw a weave structure chart that showed the complex, three-dimensional structure of a textile. But I could draw. That is probably what made me attractive. Mr Arai would come to me with an idea for a new structure, and I would first work on a drawing of it.

ー So you would draw an image of what the textile would look like?

Sudo In the beginning, Mr Arai would create the weaving structure and I would draw the pictures. I knew very little about weaving structures, materials and finishing techniques. In 1987, Mr Arai received the title of Royal Honorary Industrial Designer (Hon. RDI) from the Royal Society of Arts and was invited to the UK. I went to the UK with him, and that is when I met the textile artist Ann Sutton. She is an educator who has pioneered methods that enable hand weavers to devise and produce complex weave structures and has disseminated them in the field of education. She is an educator who has disseminated tissue charts from the field of education. Ann handed me some text books, saying, ‘You should study with these'. She told me, ‘If you are going to stay with Mr Arai, you need to become a designer who can properly create an organisation by himself, not just a superficial picture.’ When I actually opened the books, I found that there were hundreds of different weave charts in them, that I could make and decipher handloom charts, and that the charts were a universal notation system.

Handweavers in Europe and the USA design industrial textiles as a matter of course. They design weave charts and, if necessary, make weaving prototypes by hand. The structure of power looms for industrial textiles and handloom weaving is similar. On the other hand, Japan has a wide variety of dyeing and weaving traditions handed down throughout the country, each of which has developed into an important regional industry. Although fewer and fewer, the variations are the envy of the world. At the other end of the spectrum, industrial textiles are produced on power looms in countless regions from Kagoshima in the south to Yamagata in the north, where textiles that attract the world's luxury brands are still being produced today. NUNO is the result of collaboration and co-creation with the craftspeople active in these production areas.

Building relationships with production areas over 10 years

ー Mr Arai is a man who was closely involved in the field.

Sudo Mr Arai was born in Kiryu City, Gunma Prefecture, in a loom shop that weaves textiles for kimono. He said he grew up constantly listening to the sound of the loom. And the Kiryu production area is a dyeing and weaving production area with a diverse range of skills in thread, dyeing, weaving, knitting and embroidery. He was a conductor and textile planner who worked with craftsmen of exceptional skill to finish the textiles.

ー So what you learnt in this way has led you to make great strides since then? But there were still difficulties ahead.

Sudo Yes, in 1987, Mr Arai's company Antology went bankrupt and he had to leave the management of NUNO, and AXIS, which operated the AXIS building, told me that they wanted me to do my best for three years. Maybe because I was only 32 and naive, I got carried away and thought I could manage. I and a few staff took over, but it was actually very difficult (laughs).

The AXIS building also receives visits from overseas clients for design research. One time, Cara McCarthy and Matilda McQuaid, curators of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, visited us. In 1949, MoMA had featured the Bauhaus couple Anni and Albers in its first textile exhibition, and almost half a century later, they wanted to do another textile exhibition. Almost half a century later, they would like to hold another textile exhibition. There were several candidates, including India, Africa and Scandinavia, and Japan was one of them. This was the start of my journey to other dyeing and weaving regions outside Kiryu. For the next ten years, they visited Japan every year to do research. I took them from Yamagata to Okinawa. This experience led to new relationships with the production areas.

ー The exhibition "Structure and Surface: Contemporary Japanese Textiles" was held at MoMA in 1998. The uniqueness of Japanese textiles was shown to the world and had an impact. Mr Arai has provided textiles for brands such as Issey Miyake and Comme des Garçons, which were also introduced at this exhibition. By the way, Ms Sudo, do you provide textiles to brands?

Sudo I have made textiles for Donna Karan and Calvin Klein in the US. However, working with brands that have a global presence is risky, as problems often arise with delivery deadlines and quality checks. In fact, this was also the reason why Mr Arai's company was not able to stand on its own feet. When that happens, this would involve the weaver.

Textiles in space

ー Ms Sudo, you were a pioneer in promoting textiles in the field of architecture. Could you tell us how it all started?。

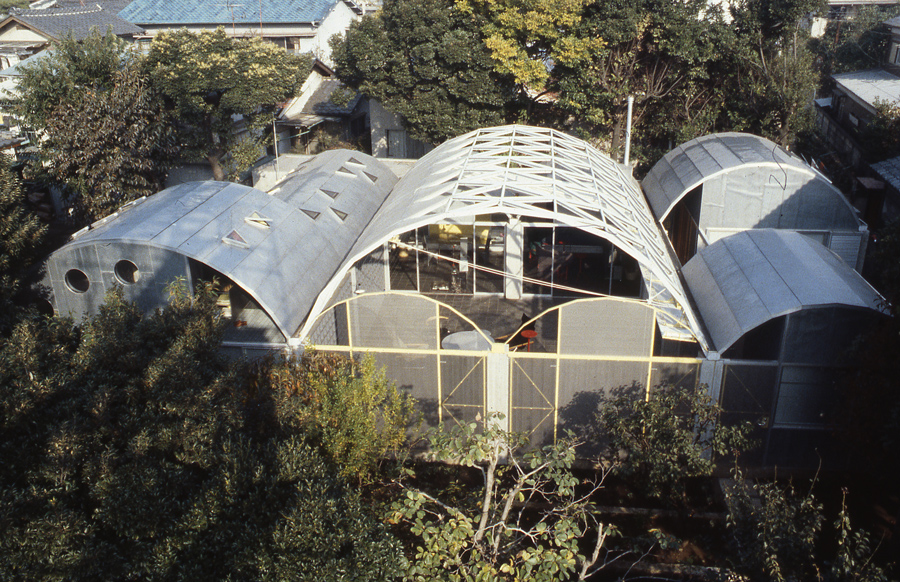

Sudo I'm not a pioneer, but Toyo Ito's own residence, "Silver Hut" (1984), was the first.

ー The same year NUNO opened?

Sudo Yes. When we first opened, we had a tough start, as there were days when not a single customer came to the shop. However, Mr Arai said to me, ‘If we make some sales, we'll pay you a salary’ (laughs). But he wasn't joking. We were in a difficult situation, so I asked my husband, who is an architect, to introduce me to someone who could help me. He did and introduced me to Toyo Ito.

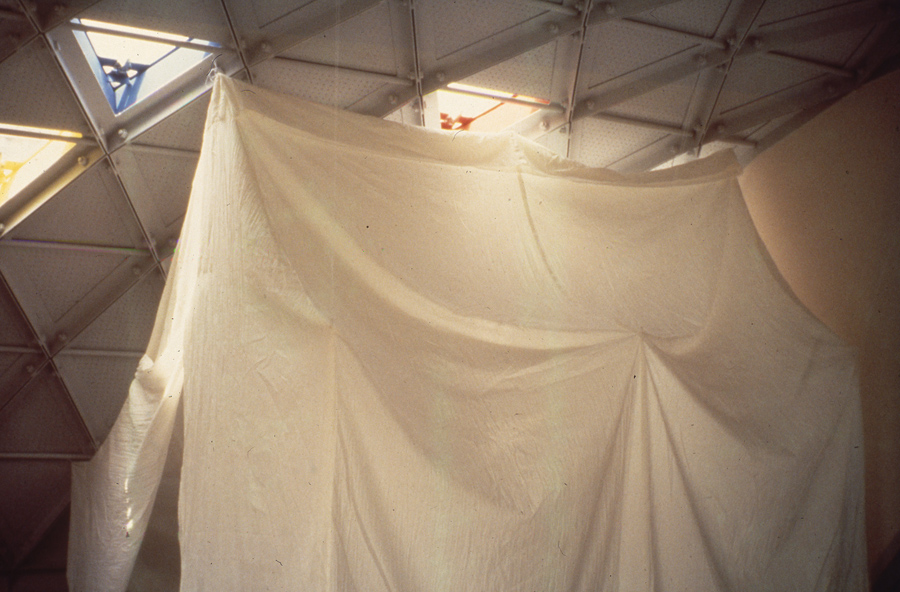

He came to the NUNO shop and said he was just planning his own house. He said, ‘You have a children's room, do you need curtains for the children's room?’ I looked at the drawings and saw that the windows are on the ceiling. ‘Are you going to hang curtains on the ceiling?’ I asked, ‘Isn't that for you to think about?’ (laughs). Mr Ito is interesting, isn't he?

I had studied the basics at Musashino Art University and had a minimum education in drawing and making models. So I made a model and suggested that we put up a tent, and he really liked it.

Then he now said, ‘One more thing. We have a stove, and I want you to build an enclosure around it so that the heat doesn't escape. Think of something. So we made an enclosure out of a highly heat-resistant fabric used by firefighters. From that encounter, I became involved in the site work designed by Mr Ito. Through that experience, I became close friends with Mr Ito.

"Silver Hut" exterior and tent/curtain inside the children's room.

Photo courtesy of Toyo Ito & Associates

ー One of Ito's early masterpieces, the temporary restaurant bar "Nomad" (1986), once located in Roppongi, is covered in fabric and expanded metal. It is no exaggeration to say that the cloth is everything.

Sudo Yes, but I only worked on the Sendai Mediatheque until it was completed in 2001. I remember being asked, ‘We need a wall in the library, can you make one out of fabric?’ I designed and drew kissing tiles for the theatre chairs at the Matsumoto Performing Art Centre (2004) and the Tama Art University Library Hachioji Campus (2007), but it was Yoko Ando who actually met with Mr Ito and made the design proposals.

Yoko Ando established her own company, Yoko Ando Design, in 2011. Ms Ando must have been responsible for most of Mr Ito's textiles since then. I think she has taken on the work of many architects, including Kazuyo Sejima and Akihisa Hirata, both from the Ito office. She is a really talented person.

Thinking about chemical recycling

ー In Japan, textiles entered the world of architecture through the collaboration between you and Mr Ito. In addition, NUNO has received work for hotels.

Mandarin Oriental, Tokyo guest room bedspread "Sunlight" through the trees, ballroom carpet "Walnut", guest room lighting "Moonlight"

Photo by Tadashi Okochi

Sudo In 2000, we took part in a competition for Mandarin Oriental, Tokyo, and we were so busy that we were unable to work on any other spaces with architects because of the sheer volume of work involved. Even today, when something bumps into the textiles used in the hotel or snags a metal fitting, or something else is damaged or inconvenient, NUNO members go to rework it.

Construction was completed in 2005, but the hotel was renewed in time for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. The service life of polyester is said to be 7-8 years with a manufacturer's warranty. The renovation was to be carried out because of the renewal, but the textiles woven with polyester after 15 years were so beautiful and strong that they did not need to be renovated. They are beyond the manufacturer's warranty period and will hold up until the next rennewal. It's beyond the manufacturer's warranty period.

ー The large-scale solo exhibition "Sudo Reiko: Making Nuno Textiles" was organised and held at the Centre for Heritage, Arts and Textile (CHAT) in Hong Kong in 2019, followed by the Genichiro Inokuma Museum of Contemporary Art in Marugame and then the Contemporary Art Gallery at Art Tower Mito in Ibaraki in 2024. Its catalogue is also a valuable archive, as is the Thames & Hudson book. In this book, you wrote that natural and synthetic fibres close life differently, which really stuck with me.

Sudo I wasn't really aware of this until around 2000. Natural fibres return to the soil. Chemical fibres are torn to pieces by sunlight and ultraviolet rays, but they do not return to the soil.

However, most petroleum-derived materials can now be chemically recycled. Therefore, when making products, we should make them from 100% polyester and 100% nylon as much as possible. Perhaps we will live in an age where it is no longer possible to throw things away. In France, a ban on clothing disposal has been in force since 2022. It is becoming commonplace to recover and become new fibres again.

Technology has also been developed that can break down hybrid items. The cost is still high, but mass-produced items are likely to move in that direction.

ー You worked as a designer for NUNO, how did your name become known to the world?

Sudo At first, I was only involved in cloth making as one of the NUNO members. In 2000, Mr Kunihiko Moriguchi, a yuzen artist and living national treasure (important intangible cultural asset), approached me to do an exhibition at the Kyoto Art Center.

When I replied that I wanted to participate as a team as NUNO, he asked me, ‘Who drew this cloth pattern? Who decided on these colours? You are the one who designed this. We should present it as your design’.

The exhibition was published in an American art magazine, which then led to exhibitions in the USA, the UK, Germany and Austria. The exhibition was held in 2001 as "NUNO - Sense and Skill".

NUNO is Arai's company, not mine. It is a shared platform. I am one and representative of NUNO, but it is not equal to me. So as a member of NUNO, I always want to be flat and fair. The NUNO textiles currently in MoMA's collection are credited as textiles designed by textile planner Junichi Arai, textile designer Reiko Sudo and Kazuhiro Ueno.

ー Could you tell us about the source of your inspiration, Ms Sudo?

Sudo I think that the idea comes from an inspiration, an idea, or something that moves me when I come into contact with some place, some thing, some person, etc.

It is ideal to come up with ideas from a simple emotional response, but I also do a lot of co-creation work with creators in the fields of architecture and interior design, so I sometimes solve problems and create new things through stimulation from outside.

There is also the starting point of thinking about how to use the technology that is available. A major turning point was the start of a chemical recycling system plant in Japan by a manufacturer of nylon and polyester synthetic fibres. This changed the direction of design and the way we think about manufacturing. We had to make products that could be chemically recycled in such a way that they would not go into that plant and cause trouble.

We used various new materials in the 80s and 90s. At the time, the new materials were revolutionary, but what happens after 10 or 20 years? Polyurethane, for example, falls apart. I think it is also necessary to change materials now that change over time, which we didn't know at the time.

ー You teach at the University of Art and Design. Young artists such as Shiori Ono have emerged, but do you also place importance on nurturing human resources?

Sudo I don't intend to nurture them at all. I don't like to use the word ‘pupil’. Professor Kazuko Koike, whom I respect very much and who is a professor emeritus at Musashino Art University, calls her students my friends. I thought that was wonderful. She once referred to me as ‘my best friend’, and I was very moved. I still remember those words burned in my ears.

ー I would be very happy if Ms Koike called me that. I think Ms Sudo is perceived in the same way as Ms Koike by people who study textiles. Finally, please tell us how you see the current state of textile production in Japan.

The Japanese spirit of newness

Sudo There is no doubt that Japanese textiles are wonderful. China, for example, was a model and teacher of Japanese textiles, but it all disappeared and was lost during the Cultural Revolution. So there are many techniques that remain only in Japan.

China is now the world's textile factory, and it houses Toyoda Automatic Loom's high-speed, high-specification, top-of-the-range machines. Only a few weavers in Japan have that kind of capital. But in Japan, that is where the human hand comes in. I think this is what other countries cannot imitate. We tame high-tech looms and modify them with our own hands. There is a spirit of always trying to create something new, like this is possible.

That's why high-end brands from all over the world come to Japan for Japanese fabrics. High fashion brands are bound by contracts, so we can't reveal that we worked on this brand. But there are a lot of factories and workshops involved, just not shown, and young people who have studied in Europe and the US have taken over and are growing up to the point where they can communicate with brands.

ー So there is still a lot to be desired. On the other hand, what are the challenges facing the production areas?

Sudo The division of labour by specialists is no longer viable. Another factor is the rising cost of transport. For example, they want to send cuts from Kyoto to Gunma, but it costs too much, so they decide to do it themselves. This would make it impossible for processing plants with special skills to make ends meet. Also, they will only be able to produce what they can do themselves. Those who specialise will seek more complex things that are not available elsewhere, and they will be refined. I think that is important.

ー You are talking about diversity, but efficiency is limiting what we can create. This trend applies to everything.

Sudo Eventually, it will be easy to make clothes by pouring polyester resin into a 3D printer. There is no loss. It may sound tasteless, but even so, high-tech tools and materials can be uniquely transformed by the involvement of human hands. I have high hopes for that. I feel that in time, the boundaries between traditional craft textiles, hand-made textiles and our industrial textiles will disappear.

ー You are at the very edge of this overlap. Thank you for talking about the outlook for textiles in Japan.