Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Kyo Toyoguchi

Industrial designer

Date: 11 May 2022, 13:30-16:00

Location: Own residence of the interviewee

Interviewee: Kyo Toyoguchi

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Tomoko Ishiguro

Author: Tomoko Ishiguro

PROFILE

Profile

Kyo Toyoguchi

Industrial designer

1933 Born in Tokyo.

1958 Graduated from Chiba University, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Industrial Design. Joined Matsushita Electric Industrial Engineering Division, Design Department.

1963 Leaves the company. Joined Toyoguchi Design Institute.

1968 Assistant professor, Faculty of Plastic Arts, Tokyo Zokei University.

1977 President of Toyoguchi Design Institute.

1984-1992 President of Tokyo Zokei University.

1994 President of Nagaoka Institute of Design.

1999 Concurrently President of Nagaoka Institute of Design.

2004-2014 Full-time President of the same.

2009 Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon

He is currently Professor Emeritus of Tokyo Zokei University and Professor Emeritus of Nagaoka Institute of Design. He is also an Honorary Professor of the Datong Academy of Engineering of the Republic of China, an Honorary Professor of Wuxi University of Light Industry (now Jiangnan University), China, and an Honorary Doctor of Dongseo University, Korea. He is also Chairman.

Description

Description

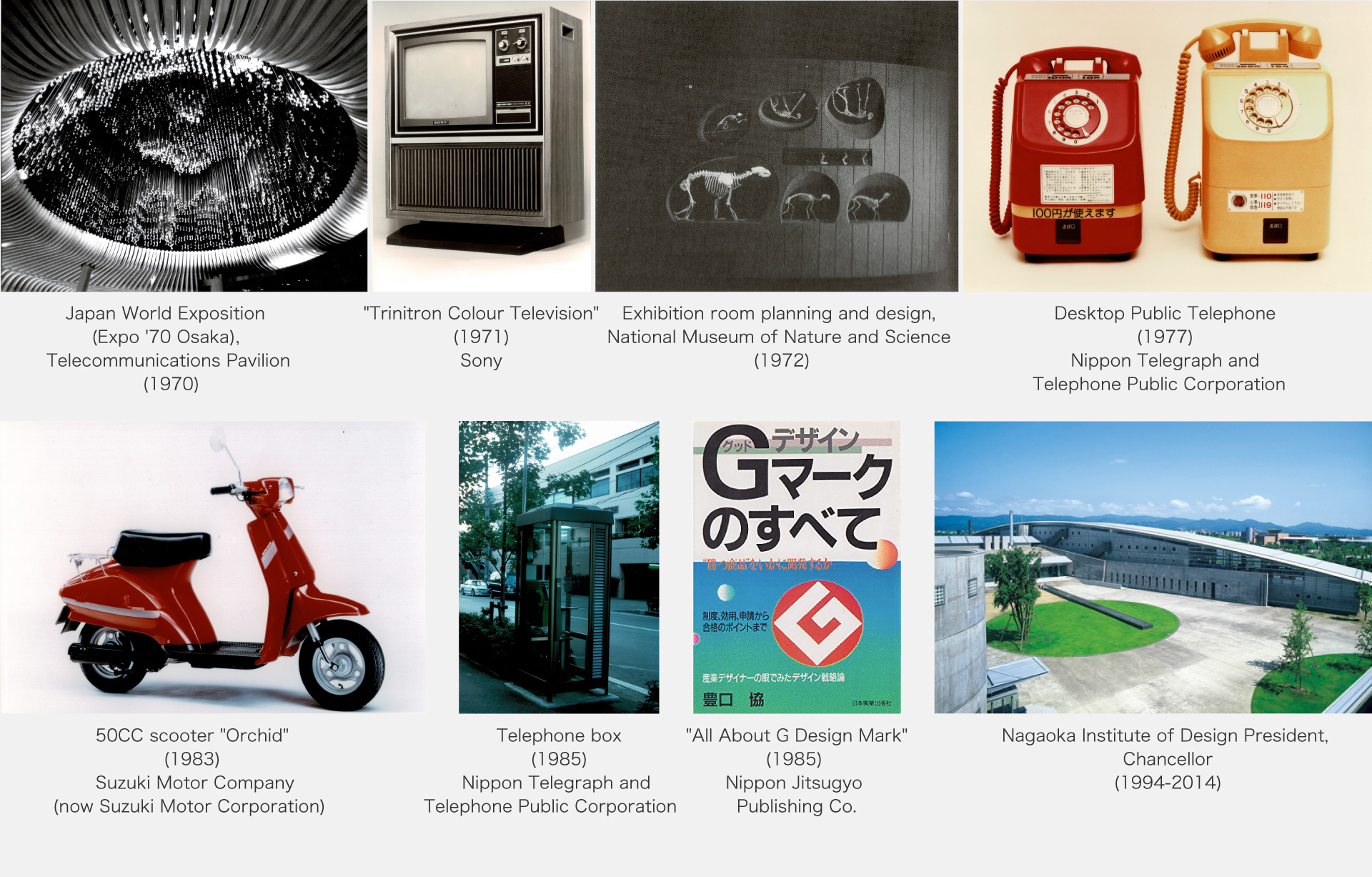

Kyo Toyoguchi has left a significant mark on the design world as an industrial designer and educator. The Toyoguchi Design Institute, founded by his father, Katsuhei Toyoguchi, who led the Japanese design world in its early days, was a pioneer in consultancy and was responsible for various design developments, basic design and planning. Projects include Sony's "Trinitron colour TV" (1971), Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation's (now Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation) mini push-button telephone "Type 700P" (1971) and public telephone (1977), Suzuki Motor Corporation's (now Suzuki Motor Corporation) 50CC scooter "Ran" (1983) and many others that everyone knows. It can be said that this work has supported in-house designers from the outside. He has also been involved in the planning and basic design of World Expos such as the Telecommunications Pavilion at the 1970 Japan World Exposition (Osaka Expo), the Toshiba Pavilion and NTT INS Pavilion at the 1985 International Science and Technology Exhibition (Tsukuba Expo) and the planning and basic design of exhibition rooms at the National Science Museum.

Following the advice of his father Katsuhei's mentor, the architect chikatada Kurata, he decided to pursue a career in design and went on to study at the same Chiba University Faculty of Engineering, Department of Industrial Design as his father, from Shinjuku Metropolitan High School. After graduation, he joined Matsushita Electric Industrial Company (now Panasonic). At Matsushita, he studied under Yoshikazu Mano, who made a significant contribution to design awareness and development within the company, and his experience laid the foundation for his later activities.

Although his days were fruitful, he left to found the Tokyo Zokei University, from where he worked as an industrial designer and educator creating the university, while belonging to the Toyoguchi Design Institute. At the time, he questioned the fact that industrial design departments were required to be as proficient as arts and crafts departments, and rethought the curriculum as requiring a scientific perspective, aiming for and realising a university that had never existed before. His experience was recognised and he was commissioned by Taiwan to participate in the founding of the Datong Academy of Engineering in the Republic of China. At the age of 60, he also embarked on a major undertaking, founding Nagaoka Institute of Design from scratch, which opened as a private school, but later went to the government and succeeded in making it a public institution. His steps in taking a broad view of design and creating new venues, while anonymous, are an essential part of the story of post-war design.

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

Telecommunications Pavilion at the Japan World Exposition, Osaka (1970); Sony "Trinitron Colour Television" (1971); Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation Mini Push Telephone "Type 700P" (1971); National Museum of Nature and Science exhibition room planning and design (1972, 73); Telecommunications Science Museum (1974); Toyota Exhibition Hall (1976); Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation public telephone (1977); Suzuki Motor Corporation (now Suzuki Motor Corporation) 50CC scooter "Ran" (1983); Yokohama Motomachi shopping mall conversion project (1985); Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation new public telephone box (1985); International Science and Technology Exhibition (Tsukuba Expo); Toshiba Pavilion and NTT INS Pavilion (1985).

Books

"The World of ID", Kajima Institute Publishing (1974); "The Japanese Corporate Museum", Dentsu Publishing Division (1984); "All About G Design Mark", Nippon Jitsugyo Publishing Co. (1985); "Facility Management Guidebook", Nikkan Kogyo Shimbun (1994); "Art Study Guidance Book, Instruction 2 and 3, Lower", Kairyudo (1995).

Interview

Interview

I don't want to do what other people have done, that's all.

As designers, we also design places for education.

ー The Toyoguchi Design Institute, led by founder Katsuhei Toyoguchi and second generation Kyo, has produced a wide range of designs, including home appliances, public telephones, motorbikes, Expo '70 and urban planning. In addition to industrial design, Mr Kyo has also been instrumental in founding universities as an educator. Today, we would like to ask you about your journey.

Mr Kyo, you went on to study industrial design at the same Chiba University Faculty of Engineering as your father from Shinjuku Tokyo Metropolitan High School, and after graduation you joined Matsushita Electric Industrial Company (now Panasonic).

Kyo Toyoguchi The Department of Industrial Design in the Faculty of Engineering at Chiba University was established at Chiba University in 1949, based on Tokyo College of Industrial Arts (Tokyo Kosen), the first design school in Japan to be founded with the aim of providing full-scale design education. I am a graduate of the sixth class, and among the first class of 1953 was Rei Kikuchi of Matsushita, the third class was Yoko Uga, who worked for Matsushita from Riken Engineering Industries (now Ricoh) before going independent, and the fifth class was Yasuo Kuroki of Sony, known for developing the "Walkman". The story of how I joined Matsushita is that when I was at university, my professor asked me to come to his laboratory and when I visited there, there was a personnel manager from Matsushita and I had an interview. I thought I was lucky to be able to enter the company after an entrance examination. I heard that the competition was 40 times higher.

ー In 1951, Matsushita created the Product Design Section as the first in-house design department in Japan. The competition rate of 40 times shows that Matsushita was a leader in the industrial design world. Yoko Uga wrote in an article about the episode of the inauguration of the Design Department that Chiba University gladly accepted Matsushita's invitation to send Mr Mano there.

Toyoguchi There is a famous episode. Konosuke Matsushita made his first visit to the USA in the same year, and when he returned home after a three-month stay, he said on the airport ramp, "From now on, it's all about design". Konosuke realised first-hand that design was indispensable for increasing the value of products in the USA, and immediately ordered the company to strengthen the personnel in the design department. He was completely at a loss when it came to selecting personnel at that time. I am told that Mr Mano's recommendation came about through a contact at Matsushita, who was a classmate of Mr Mano's from his days at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The Product Design Section expanded, changing its name to the Central Research Institute Design Department, General Design Division and General Design Centre.

ー Mr Katsuhei encounter at Tokyo Kosen led him to join the experimental designer collective Keiji-Kobo, after which he joined the National Industrial Arts Institute, where he continued his research into modernising Japanese people's lives. I felt that your experiences at school and later in the workplace were a major foundation for your career as a designer, how about you, Kyo?

Toyoguchi In my case, too, the experience of studying at Matsushita was significant. I think I was allowed to work in a good place. At first I was assigned to the Audio Division, but I requested to be transferred to a department where I could see and hear more than just audio, and was soon transferred to the General Design Division.

The work was demanding and there was a lot of overtime, but it was also fun. I learnt many things at Mano University, also described as the 'devil's' university.

In 1954, Mr Mano was awarded a special prize at the 2nd Mainichi Industrial Design Award for his "Tabletop Radio", and in 1957 he won the Mainichi Design Awards for the 'Design Department of Matsushita Electric Industrial Company's Central Research Institute, led by Mr Yoshikazu Mano'. He was also a daily advocate for us to aim for award-winning design.

He was fond of saying, "Don't design something that doesn't resemble something else. He always said, "Don't design something that is not similar to something else, just because it sells well," and that we should not design based on it. On the other hand, I remember Konosuke Matsushita telling me, "Don't design something that sells. He meant, "Design things that people are willing to pay for." I also learnt not to sell good products at a discount.

ー I can see that you had a very fulfilling time at Matsushita. But you retired after five years.

Toyoguchi That was because I was asked by industrial designer Tadashi Minagawa to help him build a new university. It is Tokyo Zokei University, which will be founded in 1966 by Yoko Kuwasawa, the founder of the Kuwasawa Design Institute. Traditionally, the boundaries between design education and art education were divided, but the philosophy of the university was to break down these boundaries and train people to practise creativity as a social activity, based on the principle of free and flexible design integration. I resonated with this and wanted to help.

While supporting Mr Minagawa, I visited various universities and conducted research in order to create a curriculum and apply to the Ministry of Education (now the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology). It was there that I came to the conclusion that the industrial design department was not something that should be taught at an art university. Traditional crafts and fine arts are 'arts' that get better the more you do them. At the time, the emphasis was on making industrial design an art to be mastered as an art. But that is not the case. When making a rice cooker, it is not only about whether the shape is good or bad, but also inseparable from the function, such as how many minutes it takes to cook the rice. We realised that we had to combine scientific elements in our curriculum. I am proud that we were able to instil a different way of thinking from conventional art universities.

ー You have now entered a new field, designing not only industrial design, but also designing educational spaces.

Toyoguchi I feel that I chose, or rather was forced to choose, a life other than being a designer. Rather than reaching out on my own, I met someone who pulled me out at some point. At Matsushita, Mano pulled me out. When I went to tell Mano that I wanted to resign, he shouted at me for quitting on my own initiative, but when I gave the reason that I wanted to build a new university, he agreed that if that was the case, then I could understand. Later, when I went to greet the executives and the factory, they told me to come back anytime if I had any problems. Those words brought tears to my eyes.

Working in the international field

ー It seems that you can see a good relationship, where you were working as a team to create things. What did you do after the Zokei University project came to an end?

Toyoguchi I was working in the Toyoguchi Design Institute, but my father was the main person in charge at the time. One day, I received a phone call from a foreign education board requesting me to submit documents and a curriculum to the Ministry of Education in the Republic of China (Taiwan) and to train newly appointed lecturers for 100 days, as they wanted to establish a university specialising in design. I was hesitant, but decided that such work abroad was not something I would be able to experience very often, and when I got there, I was welcomed with a welcome that was unbelievably favourable at the time, as it was 360 yen to the dollar and the gratuity I thought was a monthly salary was per day. This would later become the ROC Datong Academy of Engineering, which was funded by the university and the government. They were inspired by seeing Japan's reconstruction and decided that Taiwan could not survive without introducing design in the same way, so they decided to create a specialised university.

ー That is a valuable experience with design education across countries. In 1977, Mr Kyo was appointed president of the Toyoguchi Design Institute.

Toyoguchi In 1968, after completing the ROC project, I became an associate professor at Tokyo Zokei University and began working with my father on the Toyoguchi Design Institute alongside my university work. I had been asked to work as a consultant for various companies for some time, and I became involved in design development as if I were taking over the consultancy work. Olympus, Sony, Suzuki, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation (Dendenkosha Co., now NTT) and others. The Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation was responsible for public telephones and other products, but it was hard work. They wouldn't let us touch anything around the handset because we had risked our lives researching it. We were strictly told not to change the weight or angle in the slightest.

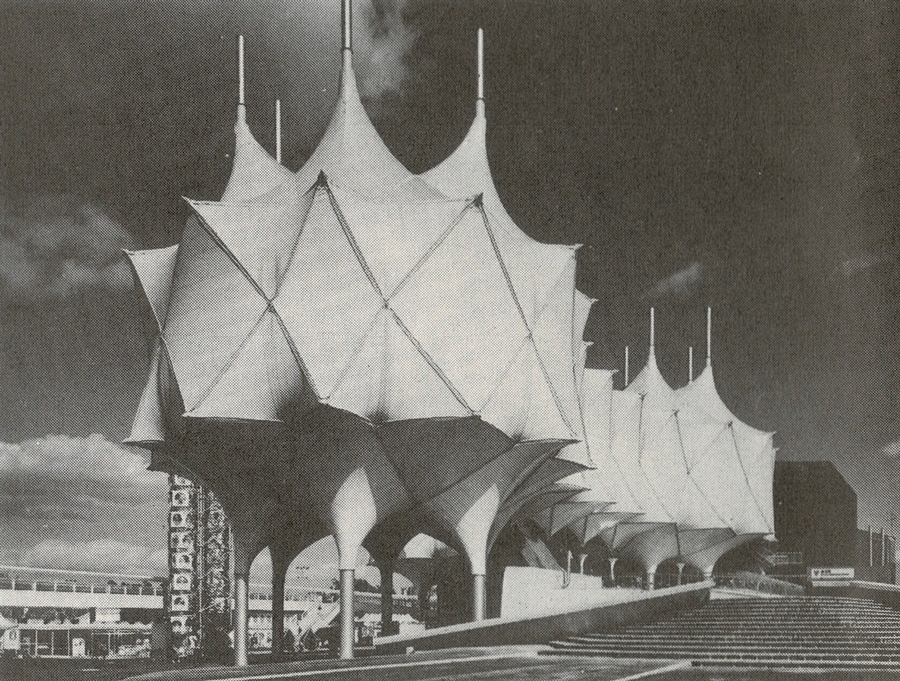

ー For a long time, engineers' opinions tended to be more important than those of designers. We often hear this in house, but the external designers you consulted had the same experience, didn't you? When it comes to the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation, the Telecommunications Pavilion was a hot topic at the 1970 Osaka World Expo.

Telecommunications Pavilion at the Osaka Expo.

Toyoguchi The Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation asked us to create the story of the pavilion. The theme was 'Human beings and communication'. I thought, 'Oh my God, this is going to be a lot of work. It's not just about displaying things like in a museum, so it's important to have a story that forms the axis. First of all, I thought about the origin of communication. Newborn babies don't speak, but the mother can understand what the baby wants to say. That is the starting point of communication. We proposed the 'Baby Space', in which 200 CRTs project images of babies of different races from all over the world, crying and laughing, as the most primitive form of communication.

ー Did you draw the sketches for these yourself?

Toyoguchi It was a team system whereby my ideas were put together by in-house staff, drawings were made, given to the Dendenkosha Corporation, and their architecture department made the drawings and finished them off. The materials were handed over to Dendenkosha and are not in our possession. In terms of archiving, most of the work, including consulting, is delivered to the client, so it does not remain in our possession.

ー In 1984, you were appointed President of Tokyo Zokei University. A new campus was also built.

Toyoguchi I was surprised when, at the age of 50, I was told at a faculty meeting that my name was on the shortlist for the presidency. I didn't think I would be chosen. The new campus was completed in 1991 after seven years of work, but the old campus had been designated a cultural monument and trees could not be cut down, so it was inevitable that we had to move and build a new campus, and plans were already in progress. However, it was only a proposal drawn up from the design documents we had submitted, and we realised that it would be a meaningless school building if it remained as it was, so we put it back on the drawing board and held a competition in 1986, in the form of a nomination. We adopted the proposal for the Arata Isozaki & Associates, with its separate layout of facilities, including a "central axis facility group", "studio group" and "atelier group", embedded in an environment rich in nature.

ー That's how it was done. The new campus by Mr Isozaki has become the face of Zoukei University, hasn't it?

Toyoguchi Thankfully, during my term as president of Zokei University, I was able to double the number of students taking entrance examinations, and after four terms I was ready to quit running the university, when the mayor of Nagaoka came to see me. He said he had heard that Zokei University was a new university that was not an art university and that he wanted a branch of the university to be built in Nagaoka. Nagaoka used to be the centre of education in Niigata. After some back and forth, he asked us again to come and build a school of our own, not as a branch of Zokei University.

Overcoming the high hurdle of turning a private university into a public one.

ー Nagaoka Institute of Design. Even though we have experience with Tokyo Zokei University and the ROC Datong College of Engineering, this time we are planning to build a university literally from scratch.

Toyoguchi We opened the university as a private university under the public-private system, but there were 32 hurdles to overcome to get there. Starting with the curriculum and personnel, we also had to have a library collection. The most difficult were the curriculum and personnel. From my own experience, I don't think general education and a second foreign language other than English are necessary for design education. It would be better to abolish them and use the spare time for specialised education. The Ministry of Education has said that we need 200 students and 72 teachers in the conventional way, but that is not enough to run a school. However, if we specialise, the number of teachers can be reduced to half of that. It would not be interesting to recruit teachers from other schools, so we have recruited freelance designers. We made sure that design is a science and that this university is not an art school.

I believe that a local university should be together with its citizens. That's why there are no walls or barriers here. The cafeteria and library are open to the public. We were surprised by the unprecedented nature of the project in many respects, but after a lot of back and forth, we were able to get approval. At that time, Niigata Prefecture told us that the next step would be a graduate school. The administration must have had some expectations, because in 1998 Nagaoka Zokei University opened a master's course in the graduate school.

ー Nagaoka Zokei University opened as a private institution, but it was a surprise when it became a public university in 2014. This is a rare example.

Toyoguchi Not a few students crossed the border to enter the university, so much so that local students could not get in, but in the long term the number of applicants was decreasing. As the university approached its 20th anniversary, there was a sense of crisis that it would not be able to continue in this way. In public schools, tuition fees are so high that some students have no choice but to drop out. With public schools, tuition fees are only 500,000 yen per year. But it is not usually possible for a private school to become a public school. We had saved and prepared our own funds by then. When we had a good idea, we went to the Ministry of Education. At first they were reluctant, but as we had plenty of our own funds and we were not going to break the quota, we were able to get approval that the conditions were right for this. I then went to Nagaoka City Hall and pleaded with them to make it public. A review committee was convened, and although it was a tough road, we managed to get our wish.

ー Why were you able to clear such a high hurdle?

Toyoguchi It's a strange thing, but I just don't want to do what other people have done, that's all. As for the funds, we had planned from the beginning to leave them behind when we first built it, and to increase them as we acquired new land and so on. There is no industry in Nagaoka, but it has a long history and is a city that is working hard.

Mr Toyoguchi wrote a column in the Nagaoka newspaper for many years. Chikako Kurosaki, a primary school headmaster in Niigata Prefecture, was so impressed by this that she edited it into a picture book for children at her own expense. The book was published under the title 'Dr Kyo Toyoguchi: "One Thousand and One Nights and One Night Stories"' (2020).

Design archive promotion activities in the 1970s

ー It can be said that Mr Toyoguchi is a person who has designed rules before they have taken shape. You said you don't have your own archive, but based on your experience of designing new organisations, if you were to create a design archive, could you tell us what it would be like?

Toyoguchi I have been working on this project with only one thought in mind: if I am going to create an archive, I want it to be something that makes people say "Wow". Around 1973, when Kenji Ekuan was chairman of JIDA, there was a move towards an archive plan to comprehensively preserve the epoch-making products that moved the times and the processes that generated them, regardless of genre, such as products and graphics. We young designers who met at the Osaka Expo got together and held a series of planning meetings. As design was gaining recognition after the Expo, we were driven by a sense of urgency: if we didn't do it now, no one else would. I served as President of JIDA from 1985 to 1990, and at that time, I put together my long-held ideas and approached the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), but unfortunately, they were blocked and the project never came to fruition. But I believe that this also led to the establishment of the National Design Museum. At the same time, designers of my father's generation were also trying to create a museum of lifestyle and culture. My father was concerned that the tools and devices used in the home were mass-produced, which led to mass consumption, and that the history of changes in life could no longer be traced. Japanese companies, which were striving for post-war reconstruction, did not have the perspective of systematically preserving the historical production that had been in place. They were concerned that most of them had not survived. Some companies now record and preserve their own history as part of their corporate culture, but they stressed the importance of preserving the 'living goods of the 20th century'.

ー So there were other activities than the inauguration of the JIDA Design Museum. These under-the-hood activities did not take the form of a 'box', but I think it can be said that they did change the mindset of companies and designers. It is assumed that there were a number of plans that did not come to fruition at the other end of the process.Lastly, I would like to ask. What do you think is important for creating a design museum in Japan?

Toyoguchi The most important thing is not to fight for the initiative, and not to start by saying whether it should be JIDA or JAGDA (Japan Graphic Design Association). Also, Japanese design is under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, but if you want to do an archiving project, I think the Agency for Cultural Affairs is the place to take the lead. It is difficult to say whether that can be done.

ー As Mr Toyoguchi created a new design school beyond the framework of the government, I would say that strong leadership is required there. Thank you very much for your time today.