Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Yoko Uga

Industrial Designer

Date: 19 December 2017, 16:00 - 17:30

Location: Uga Design Institute

Interviewee: Yoko Uga

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki、Shigeru Onawa

Author: Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Yoko Uga

Industrial Designer

1932 Born in Tokyo.

1955 Graduated from Chiba University, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Industrial Design. Joined the planning office of Riken Kogaku Kogyo (now Ricoh) and later the design department.

1957 Joined the design department of the Central Research Laboratory of Matsushita Electric Industrial (now Panasonic).

1963 - 64 Studied at Hornsey college of Arts & Crafts, UK. as a JETRO overseas design research student.

1965 Established Industrial Designer Yoko Uga's Laboratory.

1992 Reorganised as Uga Design Laboratory.

2005 Dissolution of the institute.

Assistant Professor, Department of Life Design, Musashino Art University Junior College of Art and Design; Part-time Lecturer, Department of Industrial Design, Chiba University Junior College of Technology; Member, Director and Vice-Chairman of the Japan Industrial Designer's Association(now Japan Industrial Design Association); Member and Director of the Japanese Society for the Science of Design, etc.

Description

Description

Many of Japan's industrial designers are in-house designers working for companies. They have increased in number with Japan's post-war economic growth and are now involved in a variety of areas such as business planning and branding, as well as designing products such as cars and household appliances, and are deeply committed to corporate management. At the time when Yoko Uga graduated from Chiba University and started her career as a designer, Japan was in the midst of an economic revival and the emergence of various industries, and at the same time there was a growing awareness of the need to develop products and designs that were unique to Japan and not just imitations of foreign products. In her column in the Special Issue on "Design Studies" (vol. 1, Japanese Society for the Science of Design, 1993), Uga wrote the following. "The Japanese design movement began with the opening of Japan to the outside world in the Meiji era (1868-1912). However, it was only after the Second World War that the Japanese design movement began to take off in earnest. It was in 1951 that Raymond Loewy first brought the topic of design into the public eye when he came to Japan and designed the packaging for Japan Tobacco Monopoly's Peace. The decade from then until 1960... the design activities of the '50s may be regarded as Japan's pioneering period".

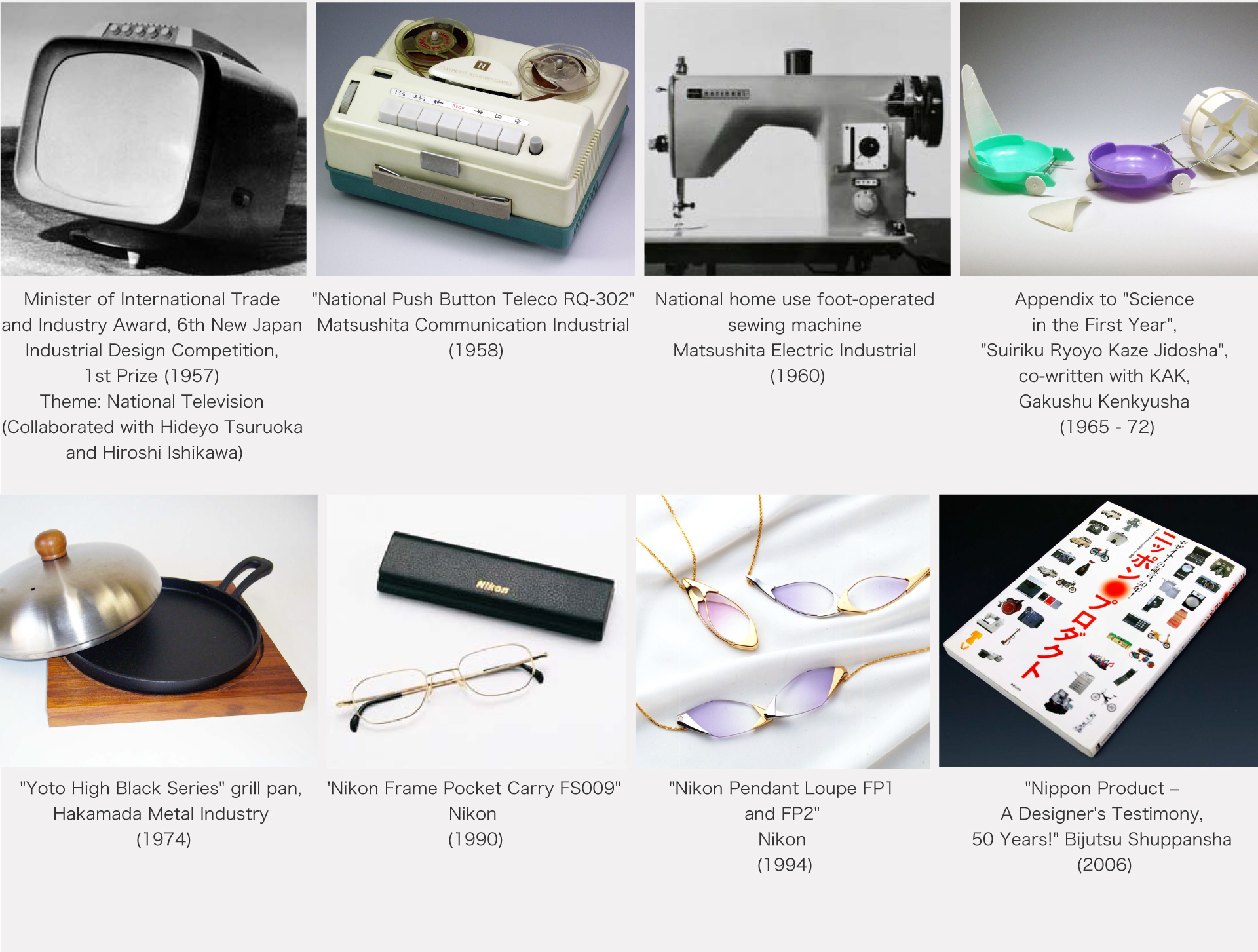

Uga's work is parallel to the development of industrial design in the post-war period. As a pioneer in the field of industrial design, she has been instrumental in raising and establishing the status of working women and women industrial designers. After graduating from university and gaining experience as an in-house designer, Uga went on to study in the UK before going freelance. She began her career designing science magazine supplements for Gakusyu Kenkyusha(now Gakken Holdings), kitchen utensils and eyeglass frames. She also actively participated in the activities of JIDA (now Japan Industrial Design

Association), which was established in 1952, and had no small influence on JIDA's design archive related projects.

Masterpiece

Products

The 6th New Japan Industrial Design Competition sponsored by Mainichi Newspaper (1957, Subject: National Television, Special First Prize, Minister of International Trade and Industry Award), Co-producers: Hideyo Tsuruoka, Hiroshi Ishikawa; Push-button tape recorder "RQ-302",Matsushita Communication Industrial (now Panasonic Mobile Communications,1958); National household foot-operated sewing machine Matsushita Electric Industrial (now Panasonic,1960); Design of a supplement for the school year magazine "Science for Fat Children", Gakushu Kenkyusha (1965-1972 ), collaboration with KAK; the grill pan "Yoto High Black Series", Hakamada Kinzoku Kogyo (1974); Nikon Frame Pocket Carry FS009, Nikon (1990); Nikon Pendant Loupe FP1 and FP2, Nikon (1994)

Essays, Books

"Kôgei News", No. 39-2, "The Life Cycle of Design: From a Survey of Actual Conditions," Maruzen (1971); The Complete Works of "Industrial Design 1 (Theory and History)", Japan Publishing Service (1983); "Nippon Product: A Designer's Testimony, 50 Years!" Bijutsu Shuppansha (2006), co-supervised with Kazuo Kimura and others.

Interview

Interview

Design was a new profession, so I had the freedom to work

Pioneer of women industrial designers

― You were one of the first post-war generations of working women, and at the same time you pioneered the field for women designers. What motivated you to become a designer in that era?

Uga At that time, the school system was revised to a 6-3-3-4 system, and it took five years to graduate from the old high school for girls, plus one year to graduate from the new high school. Japan was a very male-dominated society at that time, although it is not so different today. I was the second child and the second girl, so from a young age I was always told that it would have been better if I had been a boy, and I was always determined to be as good as the boys. Both my mother and sister had gone to higher education and I naturally intended to go on to higher education, but I could not decide what course to take. Then, in 1951, the Department of Industrial Design was established in the faculty of technology and engineering at Chiba University, and I took the entrance examination because I felt that if I studied here, I would be able to find a job in which women could play an active role. However, I did not understand what the Department of Industrial Design was.

― Was this your first exposure to design at university?

Uga Yes. At the time, Japan was struggling to recover from its defeat in the Second World War, and was becoming increasingly aware of the importance of product design. In 1951, after a visit to the United States, Konosuke Matsushita invited Professor Zenichi Mano from Chiba University to help the core of Matsushita's design. The following year, the Japan Industrial Designers Association (JIDA) was founded. In 1957, the then Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) established the system of Good Design. In these times, it was important to have a woman's point of view when it came to home appliances and other products, and demand for female designers was beginning to emerge.

― What was design education at university?

Uga I think they were in a situation of trial and error when it came to design education, wondering how they should teach industrial design to our students. In the midst of this, we learned the theory and history of design from Mr. Shinji Koike, who mainly used information from overseas, and from Mr. Masaki Yamaguchi, who taught us how to construct forms. Mr. Zenichi Mano, a part-time lecturer who later became the head of the design department at Matsushita Electric Industrial, taught us how to sketch and use paints through the industrial design exercises. I remember how impressed I was with his demonstration.

― How did you spend your time as a student?

Uga During my first two years at the university, the main subjects were general education, and I was intrigued by economics, law and psychology. There were also joint courses with students from other departments, and out of 180 engineering students, there were two women. In one of the specialised courses, Professor Koike's lecture on Nicholas Pevsner's original book "PIONEERS OF MODERN DESIGN FROM WILLIAM MORRIS TO WALTER GROPIUS" (Penguin Books) was a new experience for me. In the third year we had a factory internship, and during the summer holidays we were able to work in freelance offices of our choice. The Ministry of International Trade and Industry had a laboratory in Shimomaruko in what is now Ota-ku, Tokyo, where they conducted experiments, provided guidance and support for design development. I received my credits in the functional laboratory headed by Mr. Kappei Toyoguchi, while the rest of us worked in the design department, dismantling foreign reference products and making drawings of them.

― This kind of education led you to become an industrial designer.

Uga At the time, the main goal was to revive the industry, so the focus was on how to produce good products efficiently and in large quantities, but my practical experience in the functional laboratory led me to believe that it was important to make products that could be adjusted to suit different genders and body sizes, and that could be used without inconvenience.

― After graduation, you joined Riken Optical Industries (now Ricoh). What kind of work were you involved in at the planning office and design department where you were assigned?

Uga Ricoh had a camera division and a photosensitive paper division, and designers reported directly to the head of the planning office. Mr. Hirochika Nonaka, who was one year my senior, and we were allowed to work on anything that had the name "design" in it, such as event display and venue design, corporate mark and logotype design, in-car advertising, product packaging, instruction manuals, advertising car and camera design, and the design of newly released copiers. I enjoyed every day and was very enthusiastic about my work.

Meanwhile, from 1955, JETRO (Japan External Trade Organisation) had a system of overseas industrial design improvement researchers through an open recruitment process. The following year, the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) and others launched the 'Invitation Programme for Foreign Design Experts', and the first group of designers invited were four designers from the Art Center College of Design in the USA, including Mr. Adams, Principal of the Art Center School. I was keen to attend the course, and with the permission of my supervisor I did. There were a lot of people there who were working at the time and it was a great learning experience.

― So your time at Ricoh was very productive.

Uga I had been at Ricoh for a little over two years and had been blessed by my bosses, seniors, colleagues and my job, but at the same time I began to think that I wanted to get more involved in product design. At that time, Matsushita Electric was planning to establish a comprehensive design centre modeled after GE's design centre in the U.S., and there was talk about the need for female designers, and Mr. Mano, who had moved from Chiba University, was the head of the design department.

― You were blessed to be able to move to Matsushita at the right time.

Uga I think there was a demand for female designers at that time. However, when I joined the company, the idea of an integrated design centre had disappeared and each division was assigned a designer to work more closely with production. I was assigned to the Design Department of the Central Research Laboratory at the head office, which was responsible for taking on work for new businesses and other departments to which designers were not assigned, and I was responsible for designing a wide range of products, including refrigerators, tape recorders and sewing machines.

― Have you ever felt inconvenienced in your job because you are a woman?

Uga Design was a new profession at the time. As a result, I felt that I had a very good job because I was blessed with good people around me, and there were fewer ties and precedents of "male society". However, my salary and other benefits were much lower than those of male employees, so I asked the top management of the labor and accounting departments directly for the reasons, and at Matsushita Electric, I also asked for improvements together with my colleagues in the labor union contracted by the company.

― You then went to the UK to study, what did you learn?

Uga In the UK, the Royal College of Art (RCA) is known as a postgraduate design college, but due to problems with the procedure and timing of the entrance exam. I enrolled as a postgraduate student at Hornsey college of Arts & Crafts and was advised individually by my supervisor. Before coming to the UK, Professor Shinji Koike advised me to research UK design promotion policy through the work of the Council of Industrial Design (CoID) and the Design Centre, and gave me a letter of introduction to the head of CoID, Sir Paul Riley. This enabled me to meet the heads of the CoID departments in person during my studies and receive explanations and a better understanding of their policies, roles and methods. CoID was the first organisation in the UK to be established under the Department of Commerce as part of the national design promotion policy. Its exhibition space was opened in 1956 as the Design Centre in central London. In the 1950s and 1960s, other institutions were established in Europe, North America and Australia. In Japan, the Japan Design House and the Osaka Design House followed this trend, both established in 1960.

At CoID, design selection is always carried out by an expert committee. The selection process is also unique and the selected designs are displayed in the Design Centre. The exhibition is unique in that the selected products are presented in a coordinated manner, as if in a living space. The Design Index section of the Design Centre had a card with information on the selected products currently in production and on sale (year of release, price, designer, manufacturer, etc.) which was available for everyone to view and use. Through this experience, I became aware of the longevity of British product design, the interesting coexistence of British conservatism and innovation, and the depth of British design, which led me to conduct research on G-Mark products in Japan on the same theme after returning to Japan.

― After you came back to Japan, you started your own business instead of working for a company.

Uga In February 1965 I returned to Japan and set up my own freelance industrial design studio, Industrial Designer Yoko Uga’s Laboratory, and in August of the same year I began working with KAK to design supplements for Gakken's children's magazine, "Science for ** Years". The following year I became a full-time lecturer in the Department of Lifestyle Design at Musashino Art University and Junior College of Art and Design, and later, as an assistant professor, I also devoted myself to educational activities. One of the theme was the "Life Cycle of Design", which was the theme of my research when I studied in the UK, and I decided to investigate the actual situation in Japan. The results were published in the 1971 issue of "Kôgei News" (No. 39-2) under the title "The Life Cycle of Design: A Survey". The survey covered a total of 447 products selected for the G-Mark, including automobiles, home appliances and household goods. Compared to the UK, I was surprised to find that the mini-skirt at the time was not only out of fashion, but that designs changed every year. There is a later story: in 2013 I received an enquiry from Poland saying that they had read this article in Russian translation and would like to read it in the original, and I was impressed that they were still interested in such things more than 40 years later. To return to the subject at hand, when I was an assistant professor, there was a lot of conflict in the school, and I had to quit the university because of my own feelings.

― Is there a reason why you chose to call yourself a laboratory rather than a design studio?

Uga Perhaps I chose that name because I was interested not only in the design of products, but also in the research activity of basically thinking about the background of the product and its required functions, and analysing them in the form of data and graphs.

― Later, in 1992, the company was incorporated as Uga Design Laboratory. What would you say is your typical work?

Uga Although our organisation was incorporated, my design stance as industrial designers and the creation of my works did not change in any way, and I believe that I had a long relationship with my clients. I started working for Gakken with Mr. Yoshio Akioka of KAK. Later, between 1965 and 1972, the number of associates in the firm increased and I became involved in the design of cooking utensils such as grill pans and other tableware. Nikon's work began in 1973, and when designing the company's first spectacle frames, we started with basic research and thoroughly studied the fit and comfort of the spectacles, especially for seniors. The simple construction and ultra-compact, ultra-lightweight design made them a long-selling product. We continued to research the market for spectacles for seniors and proposed a pendant type loupe that looks like a necklace in everyday life, which also became a long seller. I also worked as an industrial designer on health equipment such as scales, various household goods and research. I have been working in this field since my days in Yoko Uga's laboratory.

― Since you were young, you said that you wanted to design products that could be adjusted to cover different body types and genders, and that were easy to use.

Uga That's right. This idea has been a consistent design theme since my university days. For example, in the design of spectacles, we have not only proposed fashionable designs, but we have also studied the differences between the Western and Japanese skeletons, and challenged ourselves to make them easier to use, fit better and be smaller and lighter.

About the Design Archive

― I would like to ask you about the design archive of you, who was one of the pioneers of women industrial designers. What is the current status of your products, drawings, sketches and documents?

Uga As you can see (there are a lot of cardboard boxes haphazardly placed in the room). There are very few materials from Ricoh and Matsushita. Sketches and drawings from before 2005, when the office was dissolved, are stored in cardboard boxes for each project, but there are still a lot of untouched materials in storage. Even after the dissolution of the laboratory, I still receive enquiries from clients, and I try to bring out the materials each time, but I have not yet managed to organise them as an archive. I am at a loss for what to do with the huge amount of material I have stored in boxes, but I feel I have to do something about it. At the moment, I am working with Mr. Onawa and other JIDA members to organise the materials related to JIDA, which I have been involved with for many years.

― As a member of JIDA, you are also involved in the publication project and the design archive.

Uga "Nippon Product - A Designer's Testimony, 50 Years!" which was published by Bijutsu Shuppansha in 2002 to commemorate JIDA's 50th anniversary, was supervised by myself, Mr. Kimura, Mr. Onawa and other JIDA members.

Onawa Through this activity, I was able to hear various stories about the dawn of product design, the beginning of JIDA and the big names from Ms. Uga and Mr. Kimura, which was a different kind of fun from the editing work and supported our activity.

― I have read it and I think it is an invaluable book for the archive, full of epoch-making moments and episodes in the history of industrial design.

Uga It was a lot of work to edit the book, which is full of sketches, drawings and photographs from the time, but as the subtitle says, it is "a design success story full of hints and tips on the origins of manufacturing", and I think it is rich in suggestions for the future of design.

― Although it is now a web magazine, the former journal "Industrial DESIGN" (Japan Industrial Design Association) is also a valuable resource for the post-war history of design in Japan. The JIDA Design Museum, which opened in 1997, and the JIDA Museum Design Selection project, which is celebrating its 20th year of selecting the best industrial designs of the year, can be regarded as design archive projects. We have covered the archive project and uploaded it to our web site, so please have a look at the details. By the way, you said earlier that you are organising the JIDA materials, what is it?

Uga The Museum Committee has taken on the task of organising the JIDA historical documents that have been stored in the secretariat for a long time, and we have decided to treat them as secondary documents in our museum activities. The large amount of work has been done over the past 20 years with the involvement of many student volunteers as well as the Design Museum Committee members.

Onawa The list is now almost complete. It includes JIDA journal manuscripts, materials from many design world conferences, as well as some snapshots, photos and audio. This is a valuable way of understanding the early days of design in Japan. We hope that the future generations will make use of these materials to make new research and discoveries.

― You sometimes visits Uga's work place, do you help her with organising the materials?

Onawa I am mainly responsible for organising the JIDA documents stored in Ms. Uga's office with the other members. Ms. Uga is a researcher, so she analyses not only the design materials but also the JIDA organisation objectively from various points of view, such as the number of members and trends. I make chronological tables and graphs of these data to make them visually easier to understand.

― This survey also shows that many designers are too busy with the job at hand to organise their archives. However, only they themselves can make the right choice of materials. I think that the materials of Ms. Uga, who experienced the pioneering days of Japanese industrial design and paved the way for women designers, are very valuable, so I hope that you will manage to compile them. Thank you very much for your time today.

Enquiry:

For questions about Yoko Uga's design archive, please visit the website of the NPO Platform for Architectural Thinking.

(Please contact us via http://npo-plat.org.)