Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Nobuhiro Yamaguchi

Art director, graphic designer

Date: 1 October 2024, 11:30-16:00

Location: Restaurant (Aoyama, Tokyo), Yamaguchi Design Office

Interviewees: Nobuhiro Yamaguchi, Tomohiro Yokokawa (Yokokawa Drawing Office)

Interviewers: Yasuko Seki, Aia Urakawa

Writing: Aia Urakawa

PROFILE

Profile

Nobuhiro Yamaguchi

Art director, graphic designer

1948 Born in Chiba Prefecture

1973 Entered and left Kuwasawa Design School

1974 Joined Jack Beans

1976 Joined Cosmo PR

1979 Independent

1996 DDA Award for Excellence in Display Design

1997 SDA Award, Runner-up Prize for Sign Design

2001 Establishment of Yamaguchi Design Office Ltd. and Origata Design Laboratory, opening of the "Hanjo furudouguten"

2002 "Rei no katachi" exhibition (Living Design Center OZONE)

2004 DDA Award Display Design Encouragement Prize

2009 7th Takeo Award, Second Prize for Excellence, Design Book Category

2011 Kuwasawa Design of the Year Award

2018 2018 Mainichi Design Awards

2019 Chairman of the Japan Book Design Awards, Japan Book Publishers Association, Contest for Bookbinding

2023 Exhibition "Sousoku no Shigaku - Nobuhiro Yamaguchi no grafikku dezain no shigoto" (Capsule Gallery)

2024 Author of the book "Boku no shimatsusho"(FRAGILE BOOKS)

Description

Description

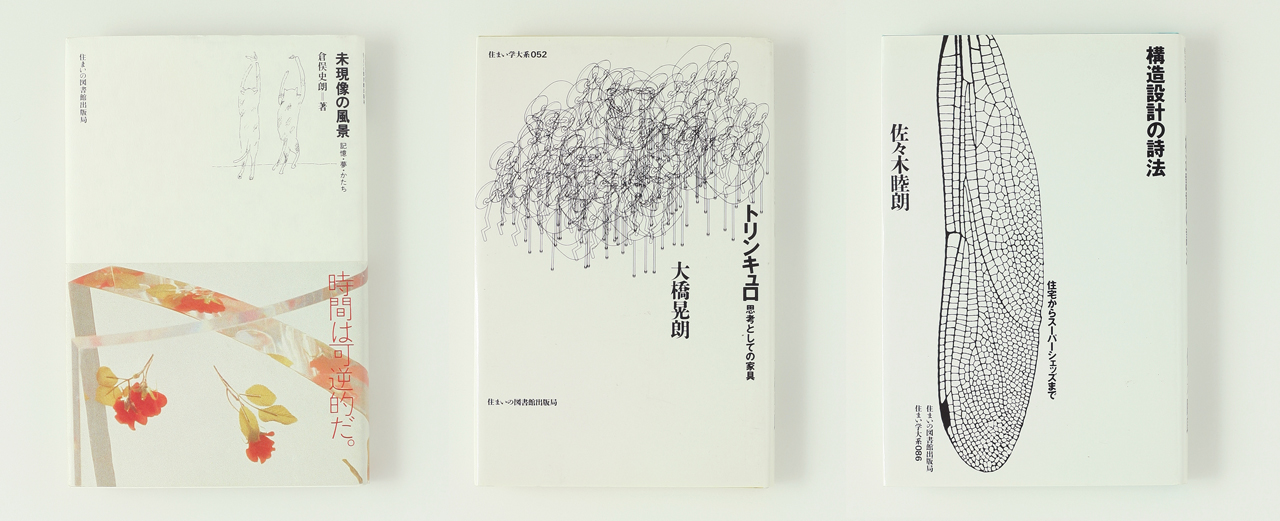

Nobuhiro Yamaguchi is a graphic designer who works mainly on book design, but also posters, packaging, CI, BI and VI. In terms of book work, one of the best-known works is the "Sumai Gaku Taikei" series of the Sumai no toshokan syuppankyoku, of which Makoto Ueda is the chief editor, having produced a total of 100 volumes since its inception. Among them are Toyo Ito's "Nakanohoncho no ie", Shiro Kuramata's "Migenzo no fukei" and Teruaki Ohashi's "Torinkyuro", as well as many other famous books by a diverse range of architects and designers. He has also designed books for a wide range of other fields, not only architects and designers, but also novelists, potters, painters, cooks, etc.

Yamaguchi began to read a lot of books when he was ill in junior high school and spent time in hospital. After entering high school, she began visiting second-hand bookshops in Jimbocho, Tokyo, where she saw books and magazines by Katsue Kitazono, Kohei Sugiura, Etsushi Kiyohara and others, which opened the door to the world of design. He then entered the Kuwasawa Design School, but dropped out. For Yamaguchi, the place of learning was outside the school, and he followed his own path almost entirely through self-study, guided by books from second-hand bookshops, encounters with teachers in various fields and personal connections.

Parallel to his design activities, he is also involved in the study of letterpress printing, haiku and origata. From an interest at the entrance, he eventually began to explore the essence of graphic design. These were then linked at the roots to form the designer Nobuhiro Yamaguchi. The appeal of his designs lies in the beauty of the Japanese aesthetic, "ma". Yamaguchi has pursued the relationship between "zu" (characters and images) and "ji" (margins). The exquisite balance and harmony between figure and ground. This is the result of his encounters with and learning from a wide range of people, and can be described as his unique personality.

Origata's research activities were awarded the Mainichi Design Award in 2018. The award recognises individuals, groups and organisations that have made a significant contribution to the design world by producing and presenting outstanding work throughout the year in all design activities. In his review, product designer Naoto Fukasawa said: "There is a quiet power in the paper and in the folds, just like his designs. (Omitted) His gaze on beautiful traditions and the spirit of design is a pursuit of quality of life that we should not lose sight of, and is a valuable activity that must be passed on from generation to generation".

Yamaguchi said that the exhibition "Sousoku no Shigaku - Nobuhiro Yamaguchi no grafikku dezain no shigoto" at Capsule Gallery in Ikejiri, Tokyo, in 2023 provided him with an opportunity to organise his own work. Tomohiro Yokokawa of Yokokawa Drafting Office, who arranged this interview, was also present to hear about Yamaguchi's thoughts on archival materials and how he created his own world view, looking back on his career to date.

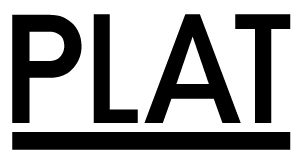

Masterpiece

Masterpiece

author, compiling and editing + book design

"Oru, Okuru" (Rutles, 2003); "Hanshi de oru Origata Saijiki" (written by Minoru Ozawa, compiled and edited by Origata Design Laboratory, Heibonsha, 2004); "Shiro no Shousoku" (Rutles, 2006); "Shin Hoyu Zusetsu" (Rutles, 2009); "Wa no kokoro o tsutaeru Okurimono no tsutsumikata" (Seibundo Shinkosha, 2010); "Tsutsumi no Kotowari Ise Sadatake ‘Tsutsumi no Kotowari no kenkyu’" (written by Yamaguchi Nobuhiro + Origata dezain kenkyujo, private edition 2013); "Kana kana no shijukunichi kana" (written by Yamaguchi Houganshi, private edition 2018); "Boku no Shimatsusho" (FRAGILE BOOKS, 2024)

book design

"Sumai Gaku Taikei"(Sumai no toshokan syuppankyoku), all 100 books; "Dezain surukoto kangaerukoto" (written by Takenobu Igarashi, Asahi Press, 1996); "Ru koubijue kappu marutan no kyuka" (written by Bruno Chiambretto, TOTO Publishing, 1997); "Jutaku junrei" (written by Yoshifumi Nakamura, SHINCHOSHA Publishing, 2000); "Muzeoroji nyumon" (co-authored by Aomi Okabe, Yoshiharu Jinno, Sachiko Sugiura and Takashi Niimi, Musashino Art University Press, 2002); "Katorari no uchu" (written by Hayao Tatsuzawa, Rutles, 2002); "Hyoden Kitazono Katsue" (written by Yasuo Fujitomi, Chusekisha, 2003); "Dezain no moto" (written by Makoto Koizumi, Rutles, 2003); "Kami no shigoto" (Rutles, 2004); "Chano no hako" (by Akito Akagi, Rutles, 2004); "Dezain no rinkaku" (by Naoto Fukasawa, TOTO Publishing, 2005); "To/to" (by Makoto Koizumi, TOTO Publishing, 2005); "Kikogoyomi" (by Kiko Nemoto, Shufu to Seikatsu Sha, 2005); "Utsukusiimono" (written by Akito Akagi, SHINCHOSHA Publishing, 2006); "Mizu to sora no aida" (written by Iino Naho, RIKUYOSHA, 2006); "Kanazawa no shigoto" (written by Yoshiaki Sakamoto, Rutles, 2006); "Oishii daidokorodougu" (written by Yuko Watanabe, Shufu to Seikatsu Sha, 2006); "Hida Kazuo sanchino gohancho" (written by Kazuo Hida, Shufu to Seikatsu Sha, 2006); "Fusuma" (written by Ichitaro Mukai and Shutaro Mukai", CHUOKORON-SHINSHA, 2007); "Utsukushiimono" (written by Akito Akagi, SHINCHOSHA Publishing, 2009); "Ito no houseki" (written by Rumiko Suzuki, Rutles, 2009); "Rakei no dezain" (written by Seiji Onishi, Rutles, 2009); "Mori e ikimashou" (written by Hiromi Kawakami, Nikkei Business Publications, 2017); "Kogei toha nanika" (written by Akito Akagi and Hiroyuki Horihata, Taibunkan, 2024)

Editorial design for magazines

Art direction of "SD Space design" (Kajima Institute Publishing), renewal of "SD" selection

posters

"Su to katachi, ten" (AXIS Gallery, 2004); "Shiro no Shousoku" (as it is, 2006 – 2007); "Niikuni, Seiichi no 《Gutaishi》" (National Museum of Art, Osaka, 2008-2009); "IN prints ON paper Yamaguchi Nobuhiro, kami no ue no shigot " (gallery yamahon, 2010); "Sousoku no Shigaku - Nobuhiro Yamaguchi no grafikku dezain no shigoto" (Capsule Gallery, 2023)

Interview

Interview

I'm involved in a lot of different things, but there is a reason for everything, and the roots are all connected

Just as there are many different ways of life, there are many different design paths

ー I would like to start by asking you about your relationship, is Mr Yokogawa a staff member of Mr Yamaguchi's office?

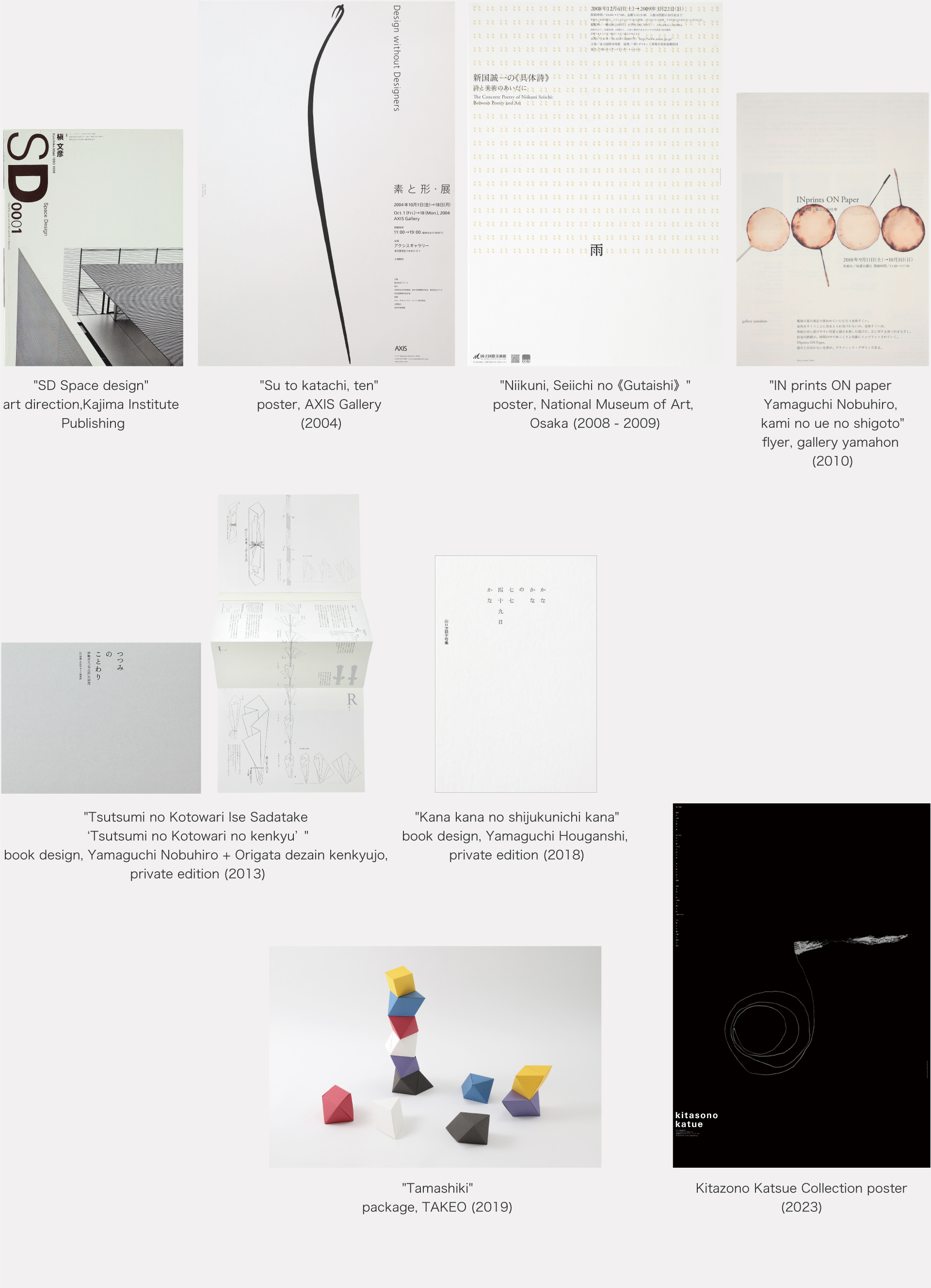

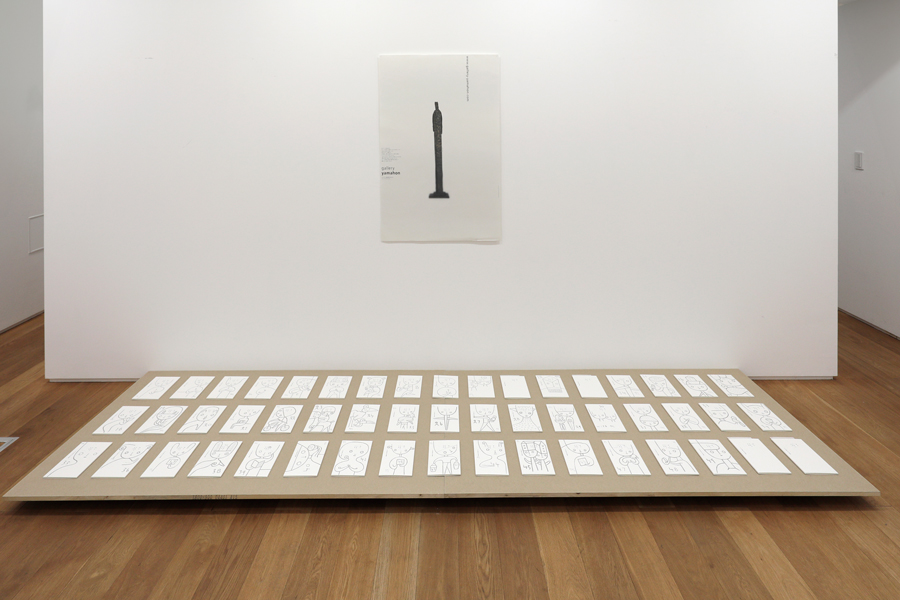

Yokokawa No, I am not on his staff, I have my own office and work as a designer. Last year, an exhibition by Yamaguchi titled "Sousoku no Shigaku - Nobuhiro Yamaguchi no grafikku dezain no shigoto" was held at Capsule Gallery in Ikejiri, Tokyo, and I was able to assist with the exhibition.

View and poster for the exhibition "Sousoku no Shigaku - Nobuhiro Yamaguchi no grafikku dezain no shigoto" (Capsule Gallery, 2023).

Yamaguchi We first met when Mr Yokokawa was supporting a farmer and he asked me for advice about making New Year's decorations using ears of rice. That project didn't come to fruition, but later I found out that Mr Yokokawa also went to the Zen meditation sessions at the temple I go to, and I thought that our interests were similar and that he was a very sincere person, so I put my trust in him. Later, Mr Yokokawa introduced me to the owner of Capsule Gallery, who was a close friend of Mr Yokokawa, and we were able to hold the exhibition last year.

ー I understand that the exhibition "Sousoku no Shigaku" was visited by a lot of young people. Is Sousoku a kind of Zen questioning?

Yamaguchi Yes, it is. Sousoku is a Zen term that refers to the idea of dynamically and infinitely reversing two opposing concepts, such as life and death, good and evil, by setting them up and negating them. I titled it because I felt the word fit when I looked back at my work to date. I've done a lot of different things, including book binding, editorial design, posters, haiku and letterpress printing, and I've divided them into six chapters in the exhibition.

ー Mr Yamaguchi, your activities are so varied that you cannot be described in one word as a graphic designer.

Yamaguchi I'm not versatile. I would say I have a lot of interests. It may seem that I am dabbling in a lot of different things, but in my mind there is a basis for everything, and I believe that the roots are all connected. I've often been asked what I do and how I came to do it, so I recently made a book.

At first I thought about publishing a book on the contents of the exhibition "Sousoku no Shigaku", but I decided to add other elements to it. For example, in the chapter "Kanakana hensoukyoku", I included haiku that I had written myself. When I left the office after the coronavirus pandemic, I was shocked to see the streets empty of people and cars, and wondered if all social activities would come to a halt and what I was going to do. I had just learned how to use Instagram from the office staff, so from then on I started posting photos and haiku every day. By the time the exhibition was held, I had about 3,000 haiku, so I made posters and exhibited them, and published them in a book.

The book will be published on 1 November by MUJI's publishing label FRAGILE BOOKS, in consultation with Mr Osamu Kushida, who is in charge of editing FRAGILE BOOKS, and it took more than a year of work but the book is finally being published. Mr Kushida used to work for Seigo Matsuoka at the Editorial Engineering Institute, and now runs a company called EDITHON.

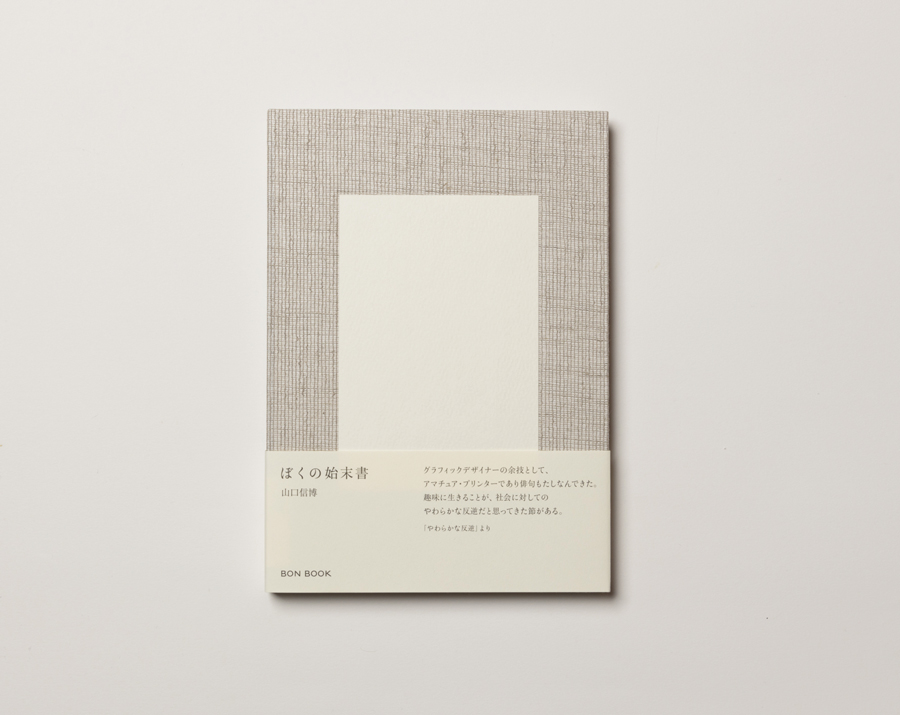

The title of the book is "Boku no shimatsusho". It's not about getting rid of the book, but about getting rid of myself, so it's a bit like a last will and testament.

"Boku no shimatsusho"(FRAGILE BOOKS、2024)

ー Is the content of this book enough to understand Mr Yamaguchi if you read it in one sitting?

Yamaguchi I don't know if you understand. There are many glittering stars who have gone before us in the field of design. I hope to be able to offer words of encouragement to young people like me, who have managed to get off the main road and make such attempts.

Just as there are diverse ways of life, there are many different paths in design. Even if you don't follow the course of going to art college to become a designer, I think it's fine if you enjoy punk and rock music while doing design, or are interested in clothes, or like chemistry, or gudja gudja. I think that if you go for the things you are interested in, they will eventually become hybridised within you, ferment and take some form, and eventually all lead to a single root, like I did.

Entering the world of graphic design

ー Mr Katsue Kitazono is also a poet, but he is involved in many different things, including editorial, bookbinding, illustration and photography, and his free way of life overlaps with that of Mr Yamaguchi. I heard that one of the people who got you interested in design was Mr Kitazono.

Yamaguchi I think I have probably learnt a lot from Mr Kitazono's way of life, which is not restricted to any particular area. I was ill in junior high school and was hospitalised for a while, so I started high school later than others. Because I was older, my classmates felt distant from me and I didn't really fit in at school, so I often skipped school and went to a second-hand bookshop in Jimbocho. Around that time, I found Mr Kitazono's fanzine "vou" at the Tokyo Do bookshop. I thought the design was cool. It was Japanese poetry, but it was in horizontal format, and he used opaque ink on paper called Maikaleido.

Other books that I often picked up because of their cool designs were those designed by graphic designers Mr Kohei Sugiura and Mr Etsushi Kiyohara. Mr. Sugiura was involved in many other experimental design books and magazines, including architectural magazines such as "a+u", "Yoshioka Minoru Shisyu" (SHINCHOSHA, 1967), Yukio Mishima's "Barakei" (SHUEISHA, 1963) and Toru Takemitsu's record jackets. Mr Kiyohara was a graduate of Tokyo University of Education (now Tsukuba University) and a member of "vou". He is also a favourite pupil of Masato Takahashi, the founder of "composition" education rooted in the Bauhaus philosophy.

ー Amidst all these things, did you decide to become a graphic designer?

Yamaguchi At that time, I still didn't really understand the profession of graphic designer. However, when I saw the work of Mr Katsue Kitazono, Mr Kohei Sugiura and Mr Etsushi Kiyohara, I thought that this kind of work was possible and that I wanted to become someone who could do this kind of work.

I lived in rural Chiba, so my art teacher didn't know about them, and when I told my father I wanted to go into that kind of field, he told me that one day I would go mad and cut my own ears off. That was Vincent van Gogh, wasn't it? Even though I thought it was different from that, I couldn't communicate it well and it was difficult to get people to understand me.

ー Were you influenced in any way by the designs of Mr Katsue Kitazono, Mr Kohei Sugiura and Mr Etsushi Kiyohara?

Yamaguchi When I was a student at the Kuwasawa Design School, there was a time when I wanted to be like Mr Sugiura. In the past, Mr Sugiura was working on three architecture monthly magazines, "Toshi Jutaku", "SD" and "a+u", the magazine "Yu", of which Mr Seigo Matsuoka was the chief editor, and many others. I think he was so busy that Mr Sugiura famously said, "A designer mustn't sleep until he is 40".

I called the editorial departments of "Toshi Jutaku", "SD" and "a+u" and asked them if they would share their allocation sheets with me for study purposes. When I apply the allocation sheets to the magazines of the time, I can see how Mr Sugiura set up the headlines, how he arranged the photographs, how he ruled the lines, and so on. But the more you learn about Mr Sugiura in this way, the more you realise that in everything he has already done. I felt that he was on a different level and that I couldn't compete with him.

ー Have you ever met Mr Sugiura?

Yamaguchi In the "SD" magazine (No. 431, Kajima Institute Publishing, published August 2000), for which I was art-directing, a special feature on books was to be published, and I once spoke to Mr Sugiura there as an interviewer. I was very nervous, but instead of my personal thoughts, I asked Mr Sugiura what the basis of his philosophy was and what he had to say about the book.

In a magazine called You (No. 8, KOUSAKUSHA, 1975), of which Mr Seigo Matsuoka was editor-in-chief, Mr Sugiura once held a trilogy discussion with Mr Katsue Kitazono under the chairmanship of Mr Matsuoka. It was rare for Mr Kitazono to participate in such a dialogue. I think it was because Mr Matsuoka and Mr Sugiura were his partners that he was able to talk openly with them. In that dialogue, Mr Kitazono said that he expressed himself in language with the pictorial works of Kazimir Malevich, the Russian avant-garde artist and suprematist, in other words, he was an imitator and had no originality of his own. And I have always been subtracting, subtracting and moving forward. He said that he hoped that all that remained would be just bones. When I realised that I couldn't compete with Mr Sugiura, I had no choice but to throw away everything I had worked so hard to absorb, and I decided to do exactly what Mr Kitazono did, which was to "subtractive progress". I decided not to use the typefaces and grid systems that Mr Sugiura often uses. I thought there was no need to use colours, and I avoided everything that Mr Sugiura did. But then I realised that there was absolutely nothing I could do. So I decided to do the opposite of what Mr Sugiura did. Mr Sugiura worked in a very tight time frame. Mr Sugiura designed the letter spacing to be packed. He also packed it thoroughly. He used the method of filling in, filling in and tightening the design. I did the opposite: I left space between letters. That took a lot of courage, and when you do that, the design doesn't tighten up, it becomes loose. As the design became looser, I kept thinking about how I could make the design work on a white sheet of paper, and I kept experimenting with it in my own way.

ー In Japanese spaces there are "ma" everywhere, such as in tea rooms and Japanese-style rooms. Is there a similarity to something like "ma" not only in the space but also in the layout of the paper?

Yamaguchi That's right. As the structure of the paper became looser and looser, I was reminded of how to use "ma" in a different way. Mr Toru Takemitsu made his debut in the 1970s and went international, using Japanese instruments to develop avant-garde music. At that time, he said in various places, "Oto, chinmoku to hakariaeru hodoni", which is also the title of his book. In other words, the "ma" of silence is equivalent to sound. I think Europeans are more conscious of the resonance between sound and sound, but Toru Takemitsu created his music from the "ma" of sound and sound, the part that is not sound.

ー I (Seki) really like Mr Yamaguchi's work, but instead of cramming a lot of information into the pages or creating "ma" unnecessarily, I feel that Mr Yamaguchi's "ma" has an aesthetic sense with just the right amount of tension.

Yamaguchi I'm glad to hear that. I am very conscious about "ma". Letters are important because they have information. But, for example, the relationship between the author's name and the title, and the distance between them I have been conscious of the design of the book. However, not everyone understood this, and editors would often redirect me by saying, ‘It would be better to put the title in the middle of the title, rather than at the edge.

ー But you have been asked to design books by various people because they all like your designs and worldview, don't they, Mr Yamaguchi?

Yamaguchi No, I am not sure about that, though.

To magazine editing and advertising production companies

ー Let me backtrack a little, what made you decide to enrol at the Kuwasawa Design School?

Yamaguchi After graduating from high school, I took the entrance exam for Tokyo University of the Arts and wasted several years. I also attended drawing classes for the entrance examinations, where the assignment was to sketch plants, replace them with coloured surfaces and compose a screen. I had gained knowledge from reading various books in second-hand bookshops, so I thought, "That's not design, that's drawing". I looked up various books to find out where modern design is taught in Japan and found the name of Mr Masato Takahashi. Mr Takahashi was running a private school, the Visual Design Institute, and I started going there after my drawing class.

Because I was doing this, I was never accepted into the University of the Arts and my academic ability was dropping rapidly. So I changed direction and took the entrance examination at the Kuwasawa Design School, where the only examination subjects were Japanese and drawing, and was finally admitted. By that time, I had become a completely overconfident and cocky student. How should I think about Suprematism?’ What a question to ask the teacher, and I would get angry. I thought it was uninteresting and ended up dropping out of school.

ー Did you work for a company called Cosmo PR after you dropped out of Kuwasawa?

Yamaguchi No, before that I worked for a company called Jack Beans. Two years above Kuwasawa, there was Mr Tutomu Toda, and as we were almost the same age, he and I got on well and talked a lot. So I was introduced to Jack Beans, which is run by Mr Tutom Toda's brother, Mr Kiichiro’s brother, Jack Beans, was introduced to us. Here he edited and designed the fashion magazine "mc Sister" and the Keihin Express PR magazine, and I helped him as an assistant. I arranged models and photographers, set up shoots and interviews, put in instructions for plate-making, arranged the inns where we stayed for interviews, ordered meals at the dinner table, and even came up with my own plans. I was always running around, always being scolded and busy.

Mr Kiichiro Toda and interior designer Mr Shigeru Uchida were classmates at the Kuwasawa Design School, so after a while they split one floor in two and set up a kind of joint office. At the time, interior designers were a blossoming profession, and it was a time when experimental design shops created by Mr Uchida, Mr Shiro Kuramata, Mr Takashi Sugimoto of Super Potato and others were being born one after another.

ー It was around the late 70s. Did you go to such shops and did you think they were cool?

Yamaguchi I thought it was cool, but it was a glamorous world, and I thought it was a different world from mine. Kiichiro Toda told me to show up at a party, and I did, but I was a non-drinker, so I quickly went home and experimented with letterpress printing on my own. Around that time, I began to take an interest in typography, and while working at Jack Beans, I also attended a private school at Mr Shigezo Takaoka's KAZUI KOUBOU, where he taught letterpress European typography. There was also a staff member from Mori Kei Design laboratory named Kazuo Horiki. Mr Horiki also came to the office, and I had study and reading sessions with him, and he showed me books on typography from overseas at the Mori Kei Design laboratory. After going there a few times, I heard from Mr Kei Mori that a company called Cosmo PR was looking for personnel, and I was able to accept an offer there and join the company.

ー What kind of company was Cosmo PR?

Yamaguchi This was the first company in Japan to pioneer the field of public relations. The vice-president, Mr Tsune Sesoko, was a cousin of Mr Sori Yanagi and an uncle of Mr Muneyoshi Yanagi, and at the Aspen International Design Conference in 1956, Mr Sesoko acted as Mr Sori Yanagi's interpreter, where she met many of the world's most famous designers, including Herbert Bayer, Eugene Smith and Max Bill. He was the Japanese Secretary General of the World Design Conference in 1960 and was involved in the TOKYO 1964 Olympic Games.

At Cosmo PR, Mr Sesoko produced corporate concept books and Takenaka Corporation's quarterly magazine "Approach". The design for "Approach" were Mr Ikko Tanaka and Mr Yasuhiro Ishimoto, and they sometimes came to the company for meetings, as well as the calligrapher Ms Toko Shinoda and many others. I was put in charge of Hitachi's overseas PR activities here, producing general catalogues, product advertisements and flyers. When I designed an advertisement using my favourite Swiss typography, I was asked to change it to a more classical typeface. Of course, I had to think in accordance with the client's wishes, and there were a lot of restrictions, so it was very difficult. I didn't have any guesses, but I left after working there for three years.

ー How did you get work once you became independent?

Yamaguchi At first I designed business cards and DMs for friends. Eventually, I started going in and out of those galleries because I like ceramics and crafts, and they started asking me to design their DMs. For example, with the ceramic artist Mr Taizo Kuroda, I bought a piece of his white porcelain at his first exhibition, which led to him asking me to design his DMs, and we continued to have a long relationship. Mr Akito Akagi, a painter, also visited an exhibition when he had just become independent, and we made a book together, and I met Mr Kazumi Sakata when I saw a DM for an exhibition at his shop, Furudougu Sakata, at the Japan Folk Crafts Museum. In that DM, there was a photo of a line of Dogon ladders from the Republic of Mali on the concrete wall of Mr Sakata's shop, and I was very intrigued by the interesting world view. So I visited the shop and began to go there frequently, and sometimes I even bought some. I then became interested in antiques and started visiting antique shops other than Mr Sakata's. Looking at the things I bought, I gradually began to understand why I liked them, and I think it also helped me to develop an eye for antiques.

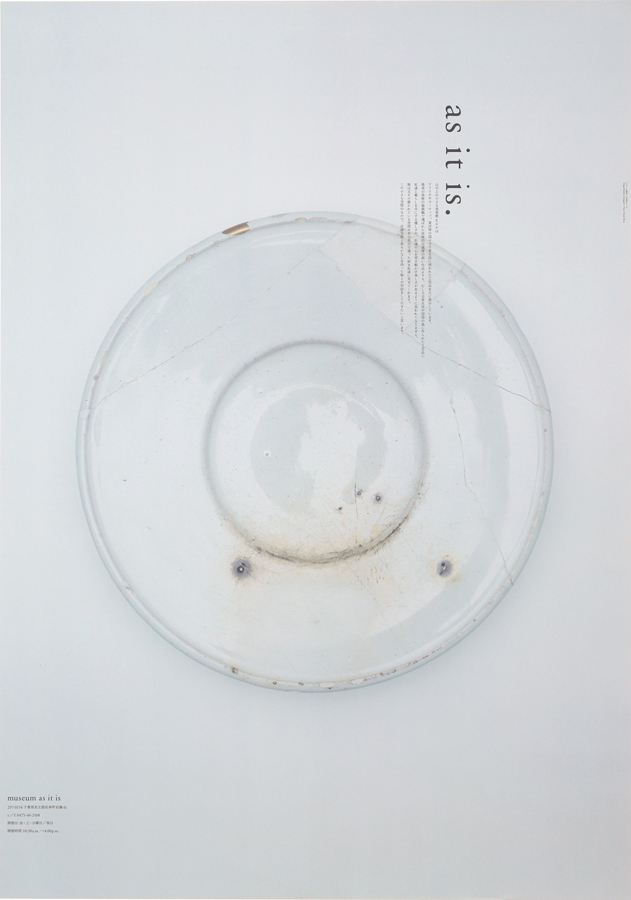

DM for the exhibition "Taizo Kuroda" (2000) and poster for the exhibition "Shiro no Shousoku" (as it is, 2006 - 2007).

Worked on Shiro Kuramata's "Migenzo no fukei"

ー I understand that you used to run a shop selling antiques, called the "Hanjo furudouguten". What is it about antiques that appeals to you?

Yamaguchi New things are just things, but old things have outlived humans, and I think that they harbour a kind of aura. Mr Naoto Fukasawa said that "Syutaku is something we designers can never compete with, something we can never design". However, design products are sold as they are, without any seasoning. I also think that the kind of syutaku and aura that is born out of people's interaction with things is an area that, unfortunately, design is not allowed to enter. I am attracted to antiques because they show the time that has passed, the degree of wear and tear, and the aesthetic sense of wabi and sabi.

ー Can we bring wabi-sabi into modern design?

Yamaguchi Modern design has in some ways eliminated such things. However, I think that the absence of such wabi-sabi is a kind of aesthetic sense of modern design. Just as Mr Kuramata tried to eliminate aura-ness to the extent possible, I think there is beauty in that as well.

Mr Kuramata once said to me, "Glass is beautiful because it breaks. What do you think?". I was surprised to learn that Mr Kuramata thinks that glass is not finished when it breaks, but that breaking and chipping is one of the possibilities of the material. At the time, he may have been in the middle of developing "broken glass" with Mihoya Glass.

ー You met Mr Kuramata in the production of the book "Sumai Gaku Taikei" for the Sumai no toshokan syuppankyoku, of which Makoto Ueda was the chief editor. Can you tell us about any episodes during the production?

Yamaguchi I was introduced to the work of Sumai Gaku Taikei by its editor, Mr Shukuro Habara, and was involved in the design of the magazine from its first issue in 1987. Among the various projects I worked on, I was most impressed by Mr Kuramata. I produced a book titled "Migenzo no fukei", and I visited his office several times with the editor in charge. He is a shy person and speaks in small talk, but it was all very contained and interesting. For example, he said, "Every day on my way to the office (from home to office) by train, I see three chairs on the roof of a building, and they are moving every day". One of the chairs is a folding chair and sometimes it is folded up, and the position of each chair changes slightly. "It's like watching the drama of the chairs on the roof, and that's what I look forward to every day", he said.

Mr Kuramata also wrote a bit about this in "Migenzo no fukei", but it seems that during the war, silver paper was sprayed on B-29s to disrupt radar detection before they bombed them, and when it was sprayed everyone rushed to hide in air-raid shelters, but Mr Kuramata said he kept looking at it because it was so sparkly and beautiful. Mr Kuramata used to watch them all the time because they were so sparklingly beautiful. During classes at school, he was often lost in thought, looking outside instead of at the blackboard, so the teacher was worried and called his parents to warn them, but Mr Kuramata's father firmly said, "Don't mess with Shiro". That's why I thought that Mr Kuramata's talent was not broken in the middle and he grew up as he did.

Book design for the "Sumai Gaku Taikei", published by Sumai no toshokan syuppankyoku. From left to right: "Migenzo no fukei" by Shiro Kuramata (1991), "Torinkyuro" by Teruaki Ohashi (1993), "Kenchikusekkei no shihou" by Mutsuro Sasaki (1997).

ー That's an interesting story. Just as Mr Kuramata considers the breakage of glass to be a possibility, I think that Origata, which you are researching, is also pursuing the possibilities of the paper material itself. How did you first become interested in it?

Yamaguchi It was at Oya Shobo, an antiquarian bookshop in Jimbocho dealing with old books from the Edo period, that I came across a book called "Tsutsumi no Kotowari" by Sadatake Ise, a deceased family member from the late samurai family of the mid-Edo period. It had a spread of net drawings and finished drawings of various Origata. There were Japanese captions in places, but I didn't really understand what they meant, so I decided to buy it. I did some research on my own, but I didn't understand it, so I went to the Yamane Origata School with Mr Akihiro Yamane, who taught me about Orikata. After about three years, Mr Yamane became ill and started a study group with volunteers. I named the group the Origata Design Laboratory. In addition to what he had taught us, we thought it would be a good idea if we expressed our own original ideas in an exhibition, so we asked Mr Yamane about it and he said, "It's very interesting, I think it's good".

As a matter of fact, when I was preparing for that exhibition, the Japanese paper craftsmen from Mino, where the next exhibition was to be held, came to see the venue and when I told them about this activity and that I wanted more of this kind of paper for it, they said, "Why don't you come to Mino once?". From then on, I began to go to Mino several times, and while I was allowed to experience papermaking, I learnt that I could design the quality and thickness of paper by myself, and I felt as if the front of my eyes were opening. I also learnt that the paper I used to choose from sample books was developed for the convenience of printing machines and bookbinders.

Another thing I felt during the papermaking experience is that the purity, spirituality and aura of paper is due to the fact that paper is made by passing through water. Origata is a gift that can be used to express gratitude and condolences when given to others, so I thought it would be best to use paper made by human hands through such water for Origata.

ー I don't know if you can call folded forms graphic, but instead of drawing something on paper, Origata make use of the paper itself.

Yamaguchi Graphic design conveys a message with words and images on a support called paper, but in Origata there are no images or letters at all, and the message is entrusted to the object itself. I thought there was an overlap between this and haiku. For example, haiku does not talk about feelings such as liking, disliking, being angry or frustrated. In fact, it would be better if haiku could be composed only with nouns, but we entrust our thoughts to the nouns. You can take it any way you like. In the Origata, if you wrap a pencil as a gift, you are entrusting some kind of feeling to that pencil. It could mean "Please write to me" or "This is goodbye".

In other words, both haiku and Origata are communication that only works between the two. It is quite advanced, and I think it has a different dimension to graphic design communication. Through the world of haiku and Origata, I learnt that Japanese people have a history of communicating in such a way that they read each other's airs. At the same time, studying haiku and Origata made me realise what modern design has discarded or overlooked, and conversely, it gave me an opportunity to think about what we have lost in traditional things.

Connecting the dots archive

ー Finally, I would like to ask you about the current state of your archive. I understand that you once organised your work at last year's "Sousoku no Shigaku" exhibition and wondered what you would do with it in the future. Was that exhibition the catalyst for your decision to organise your archive?

Yamaguchi It was just around 40 years after I established my office when I was approached about the "Sousoku no Shigaku" exhibition. Mr Sakata also held an exhibition about 40 years after he started his antique shop, and I think that after 40 years or so, everyone reaches a milestone in doing something. In preparation for the exhibition, I organised the materials of my 40 years of work by categorising them and creating a hierarchy.

As I was sorting through them, I remembered how much fun I had at that time and how painful it was at that time. But as I organised, I realised that there was only so much a person can do in a lifetime, and that I was limited. Then I started to think that I had nothing to show people and that I didn't need to show them.

While I was sorting out the materials, Mr Yokogawa became my adviser. My head was all messed up and I was mostly just complaining. He gave me advice and said, "There's another direction you could take", and I think that's how we managed to realise the exhibition.

Yokokawa An exhibition is like the crystallisation of a single answer, but Yamaguchi's exhibition was divided into six chapters, and there was a fluidity in the way it was constantly reconfigured on the spot, which I think was the opposite of a typical exhibition. "Kappan" is called "movable type" in English, and the typeface itself has a fluidity that allows it to be reconfigured. In that sense, I think it was a very typical Yamaguchi exhibition.

Yamaguchi As Mr Yokokawa just said, in "Kappan", the type is taken out of the sudare case, jacked in place, printed, and then put back into the case again when printing is finished. At some point it crystallises and it can be dismantled at any time, it disappears in an instant. Many people say that letterpress is good for the pressure it puts on the paper, but I think it's interesting in that it's like a fluid cloud that once it has taken shape, it quickly disappears.

ー There is such a fascination with "Kappan", isn't there? I would like to ask you about the specific archive material: what kind of posters do you have and how are they stored?

Yamaguchi I keep my posters in a map case. I am not a poster artist, but I have tried to make posters based on haiku. First, I asked Mr Minoru Ozawa, a regular haiku instructor, to select some highly rhymed masterpieces, and then I decided to use romanized notation to reduce the haiku to sound. I made 12 B-wide posters with the ones selected by Mr Ozawa in romanised form. When I was laying out the posters, I said out loud, "Fuwa fuwa no fukuro", while thinking about the composition, and at that time I was reminded how fun design can be. I rented a space in Omotesando Station for a year and changed 12 posters every month. The designers seemed to look at them quite a lot.

Then I found out that Tama Art University had the Kitazono Katsue Collection, and for five years I made posters of Mr Kitazono Katsue on the anniversary of his death, although I was not asked to do so.

Also, Mr Kazumi Sakata was going to hold an exhibition of his personal collection at his museum "as it is" in Chiba, and I was honoured to be the first one to be nominated. The main purpose of the exhibition was to ask me to exhibit my own collection, and I paid for it all myself, even though I was not asked to do so, and planned and published a book like a catalogue called "Shiro no shousoku" (Rutles, 2006), which was a compilation of the exhibited items. Then I was asked to make a book for the next exhibition of another person's collection, which I did. Therefore, I thought it was important to design something on my own, even though I was not asked to do so. I also thought there was a way to get out of the scheme of being asked and responding.

ー There are people watching, that's what. It's better to have 10 people who are interested in seeing it than 10,000 people who are not interested.

Yamaguchi I knew that I didn't have a mass appeal, so I think that if just one or two people see my work and feel it, that's all that matters.

I don't think I've ever had anything solid to express, but I sometimes wonder if I'm made up of the grace of the people I've met. Whenever I reach a dead end, I have encounters, and I think that I really live by a variety of connections.

ー You have been guided to meet a wide variety of fields and so many wonderful people. How do you keep the books you have designed and the books in your collection?

Yamaguchi There are a lot of them. I sold design-related books before. I thought now was the time to let them go, so I also got rid of quite a few that I thought would be quite important materials. I have kept some old books and materials related to Origata. I have about two cardboard boxes of magazines, including the first issue of Mr Katsue Kitazono's "vou", and books he bound. I took them to an antiquarian bookshop that understood their value, but the purchase price was so low that I gave up selling them. There is also a considerable amount of antiques.

ー I understand that you keep your proof sheets in a box.

Yamaguchi Proofreading papers are stored in boxes for each project, and there are about 20 boxes in total. The boxes were made by the bookbinder Mr Tatsuhiko Niijima. The boxes contain enough first drafts and re-scripts to show the level of printing in this period if a bibliographer were to look at them in the future.

In it, for example, the novelist Ms Hiromi Kawakami used to write a series of articles for the Nihon Keizai Shimbun for a year and a half, which were turned into a book called "Mori e ikimashou" (Nikkei Business Publications, 2017). Designer Mr Akira Minagawa did the illustrations for that, and I did the editorial design. The box contains newspaper clippings, proof prints, a draft of the binding, and specifications for paper changes, etc.

ー Why did you decide to keep your proofreading paper in a box?

Yamaguchi As I wrote in the preface to "Boku no shimatsusho", when I was working on Mr Kuramata's "Migenzo no fukei", I received the last page as a manuscript from the editor in charge, laid it out on the spot and submitted it for publication. That night I received a phone call from the editor saying that Mr Kuramata had passed away. The last page was an X-ray photograph of Kewpie, whose wings moved mechanically. So, Mr Kuramata never saw the finished book. So I put the proofs together and placed them in his casket in time for his funeral.

The book "Migenzo no fukei" is about your memories and dreams from your childhood, isn't it?. Memories and dreams are things that no one can know about unless they are verbalised and visualised, and they do not appear on the surface. Mr Kuramata verbalised them in his book and visualised them in his sketches. From a skeptical point of view, what should have been left untouched was pulled out into the daytime world, and what had been hidden was brought into the open. I thought that by doing so, the worlds of the unconscious and the conscious, life and death, had been switched, and I thought that the work of making a book was terrifying.

ー You mentioned that you put the proofs of the "Migenzo no fukei" book in Mr Kuramata's coffin, but a coffin means that you put everything about the person in it and leave it to the fire, doesn't it? For Mr Yamaguchi, does putting the proofs in a box mean that you are not putting an end to the book, but that it is a step before the book is finished?

Yamaguchi Essentially, putting it all together in some form of book is also about putting yourself in something once, putting a period on it. But I wanted to make sure I didn't put a period on it, and that's how I ended up putting it in a box.

ー That's how it came about. Have you ever thought about donating the material, including those boxes, to a university or museum?

Yamaguchi I didn't go to university, so I don't have any connections. I actually have a second house in Chiba, which was designed by architect Mr Yoshifumi Nakamura. My father passed away this year, so I'm just now starting to sort out the house, which has almost become a warehouse. A real estate agent told me that even though the house was designed by a well-known architect, the building has almost no real estate value, and on top of that, my house is in a satoyama in Chiba, so the land value is not that high. He advised me that it is not worth owning as real estate and that I should use it up in the years I have left. When I heard this, I wondered if there was an idea that it would be more valuable to use rather than sell. I thought about what kind of use I could make of it, and I thought it would be a place like a gallery where people could look at the things I made and collected. I'm also thinking that it would be OK to give it away to people who are interested in it, and I don't mind if the materials are scattered around.

When I created the Origata Design Laboratory, I once ran a shop called the "Hanjo furudouguten", where I laid out antique items on a half-tatami mat. When you work in design, you only connect with people in a certain limited field, such as editors and photographers, but when you have an open space like a shop, you realise that you can make connections with people in different fields, and I am looking forward to expanding my relationships with people again.

I have a space that I can freely use, rather than relying on public places such as universities and museums, so I intend to use it to its fullest from now on. I hope to be able to open it in the next spring or so.

ー I'm looking forward to it. I would love to visit when it is completed. Thank you very much, Mr Yamaguchi and Mr Yokokawa, for your valuable time today.

Enquiry:

Yamaguchi Design Office Ltd.

https://www.yamaguchi-design.jp