Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

Shunji Yamanaka

Design Engineer

Interview: 25 Mar 2025, 15:00-17:00

Location: Shunji Yamanaka Laboratory, Komaba Research Campus, the University of Tokyo

Interviewee: Shunji Yamanaka

Interviewer: Yasuko Seki

Author:Yasuko Seki

PROFILE

Profile

Shunji Yamanaka

Design Engineer

1957 Born in Ehime, Japan

1982 Graduated from the University of Tokyo, Faculty of Engineering, Department of Engineering Synthesis

Joined Nissan Motor corporation and worked at the Design Centre

1987 Became independent and worked as a freelance designer

1991 Appointed project associate professor, the University of Tokyo (-1994)

1994 Established Leading Edge Design(LED)

2004 Winner of the Mainichi Design Award

2008 Professor at Keio University (-2012)

2013 Professor at the Institute of Industrial Science, the University of Tokyo

2023 University Professor at the University of Tokyo

Description

Description

From the late 1980s to the early 1990s, when Shunji Yamanaka began his freelance career, Japan was in the midst of a paradigm shift, and design was undergoing a seismic change. For example, Japan's economic growth and unprecedented bubble economy burst in the blink of an eye, ushering in the ‘lost 30 years’. The world was recognised as a global village with finite resources and environmental limits, prompting the search for alternatives to the mass production and mass consumption society. With the widespread adoption of Apple's Macintosh and Microsoft's Windows, computers were introduced into design development, fundamentally transforming the site. These changes were further accelerated by the subsequent development of the internet. For designers, the era where they could simply create stylish and beautiful designs based on the principle of ‘form follows function’ had come to an end.

At that time, the emergence of designer Shunji Yamanaka was something of a sensation. With his degree from the University of Tokyo, Yamanaka attracted attention as someone who embodied the image of a new designer for a new era. As expected, he opened up the field of ‘design engineering’ in the design world and established a new profession called ‘design engineer.’ He then produced many works with his unique approach of ‘envisioning the future with technologies currently under development’. He challenged areas that designers before him had not touched, such as the prototype for the IC card-based transportation system ‘Suica’, prosthetic limbs that blend functionality and beauty, and cutting-edge robots, and achieved results.

As an educator, Yamanaka taught at Keio University and his alma mater, the University of Tokyo, where he practised design thinking education and nurtured many younger generations. His own office, ‘Leading Edge Design (LED),’ attracted many young people with science and engineering backgrounds and resembled a design engineering laboratory. Many talented individuals, including Kinya Tagawa and Hisato Ogata (takram), have emerged from Yamanaka's office. In September 2027, the University of Tokyo will establish a new faculty, the ‘UTokyo College of Design,’ for the first time in 69 years, and it is likely that Yamakawa's long-standing achievements at the University of Tokyo have had a significant influence on this decision.

The root of Yamakawa's creativity lies in Manga. In this interview, we asked Yamakawa, who continues to draw manga to this day, about his journey, the future of design, and design archives.

Masterpiece

Main works

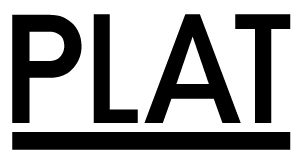

Camera ‘O-Product’ Olympus (1988)

Wristwatch ‘Asterisk’ Seiko Instruments Inc.(1988)

Passenger car ‘Infiniti Q45’ Nissan Motor Co., Ltd. (1989)

Camera ‘Ecru’ Olympus (1991)

Conventional Line High-Speed Experimental Vehicle E991 Series ‘TRY-Z’ East Japan Railway Company (1994)

Two-Thumb Keyboard 1for Japanese ‘Tagtype’ Leading Edge Design (2000) Co-developed with Kinya Tagawa and Jun Honma

Wristwatch ‘INSETTO’ ISSEY MIYAKE, Seiko Instruments Inc. (2001)

IC Card Automatic Ticket Gate System ‘Suica’ East Japan Railway Company (2001)

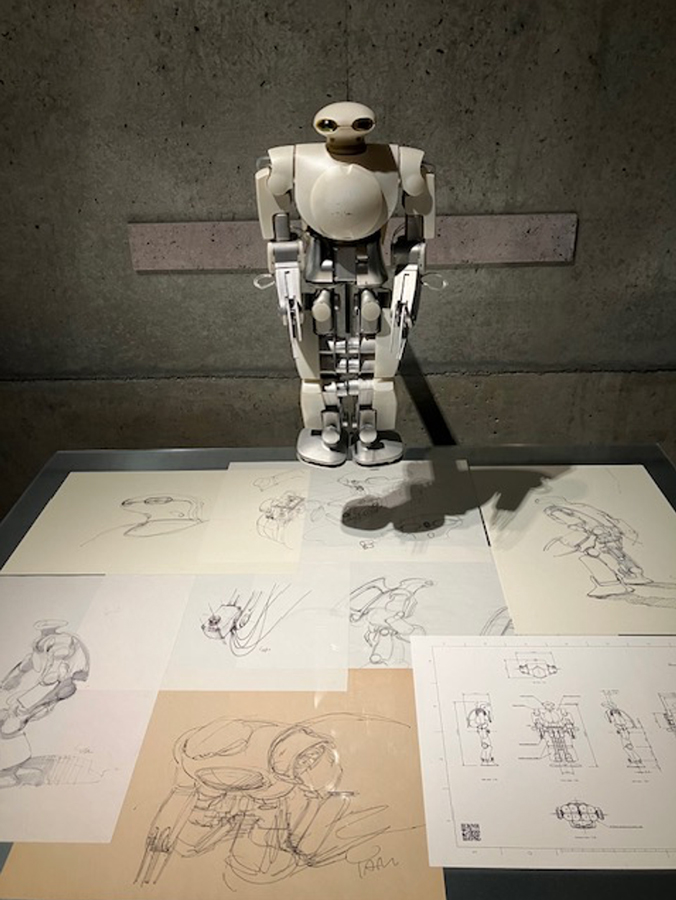

Humanoid Robot ‘Cyclops’ National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Ars Electronica Center, Expo 2005 Aichi (2001)

Humanoid Robot ‘Morph3’ (2002) Co-developed with Takayuki Furuta, ERATO Kitano Symbiotic Systems Project

Office system furniture ‘S-chair’ and ‘S-table’ SUS (2003) Co-developed with Riken Yamamoto & Field-Shop Co.,Ltd.

Mobile phone prototype ‘OnQ’ NTT DoCoMo (2004)

PHS mobile phone SIM card ‘W-Sim’ and mobile device ‘TT’ Willcom (2005)

Robotic vehicle prototype ‘Halluc II’ (2006) Co-developed with Takayuki Furuta + fuRo*

Kitchen tools ‘Daikon Grater’, ‘Precision Tongs’, ‘Serving Tool Set’ OXO International (2006)

Robot Installation ‘Ephyra’ Leading Edge Design (2007) Co-developed with Wakita Laboratory, Keio University

Office Chair ‘AVEIN’ Kokuyo (2009)

Robot Installation ‘Flagella’ Yamanaka Laboratory, Keio University (2009)

Para-athlete prosthesis ‘Rabbit 4.0’ Yamanaka Laboratory, Keio University (2012) Co-developed with Prosthetist/Orthotist Fumio Usui and Imasen Engineering Corporation

3D-printed prosthetic leg for athletes ‘RAMI’ (2016) Co-developed with Niino Laboratory, University of Tokyo, and prosthetist/orthotist Fumio Usui and Yamanaka Laboratory. SIP ‘Manufacturing Initiative through AM Innovation’

Mobility Robot ‘CanguRo’ (2018) Co-developed with Takayuki Furuta + fuRo

Project ‘Augmented Driving’, Honda (2020)

Smart-watch ‘WENA3’ UI and watch head, Sony (2020)

EV quick charger ‘Multi 6’ e-Mobility Power, Nichicon (2021)

‘Jizai-shi’ (2023) Co-development with ERATO Inami Jizai-Body Project and Yamanaka Laboratory

*fuRo: Future Robotics Technology Research Centre, Chiba Institute of Technology (Director: Takayuki Furuta)

Main publications

“Human and Technology Sketchbook” series, Taiheisha (1997)

“Future Style”, ASCII Publishing (1998)

“Skeletal Structure of Design”, Nikkei BP (2011)

“Carbon Athlete”, Hakusuisha (2012)

“X-DESIGN”, Keio University Press, co-author (2013)

“The Little Bones of Design”, Nikkei BP (2017)

“You Too Can Design”, Asahi Shuppansha (2021)

Interview

Interview

To Young Minds: Don’t Tie Yourself to One Specialty

A Society That Honors Their Freedom

The path to becoming a designer

ー You are now known as a design engineer, but can you tell us how you went from engineering to design?

Yamanaka I was born in Matsuyama City, Ehime Prefecture, and played in nature when I was a child. I also liked drawing pictures. I was not good at sports, but I could study reasonably well, so I went straight to a local school and studied hard for the entrance examinations and entered Tokyo University. After a while, however, I developed May Sickness and was unable to concentrate on my studies for a long time. It was then that I remembered how I used to draw as a child, so I picked up a comic book that was nearby and tried to copy it.

ー There are also oil paintings and illustrations, but why did you choose manga?

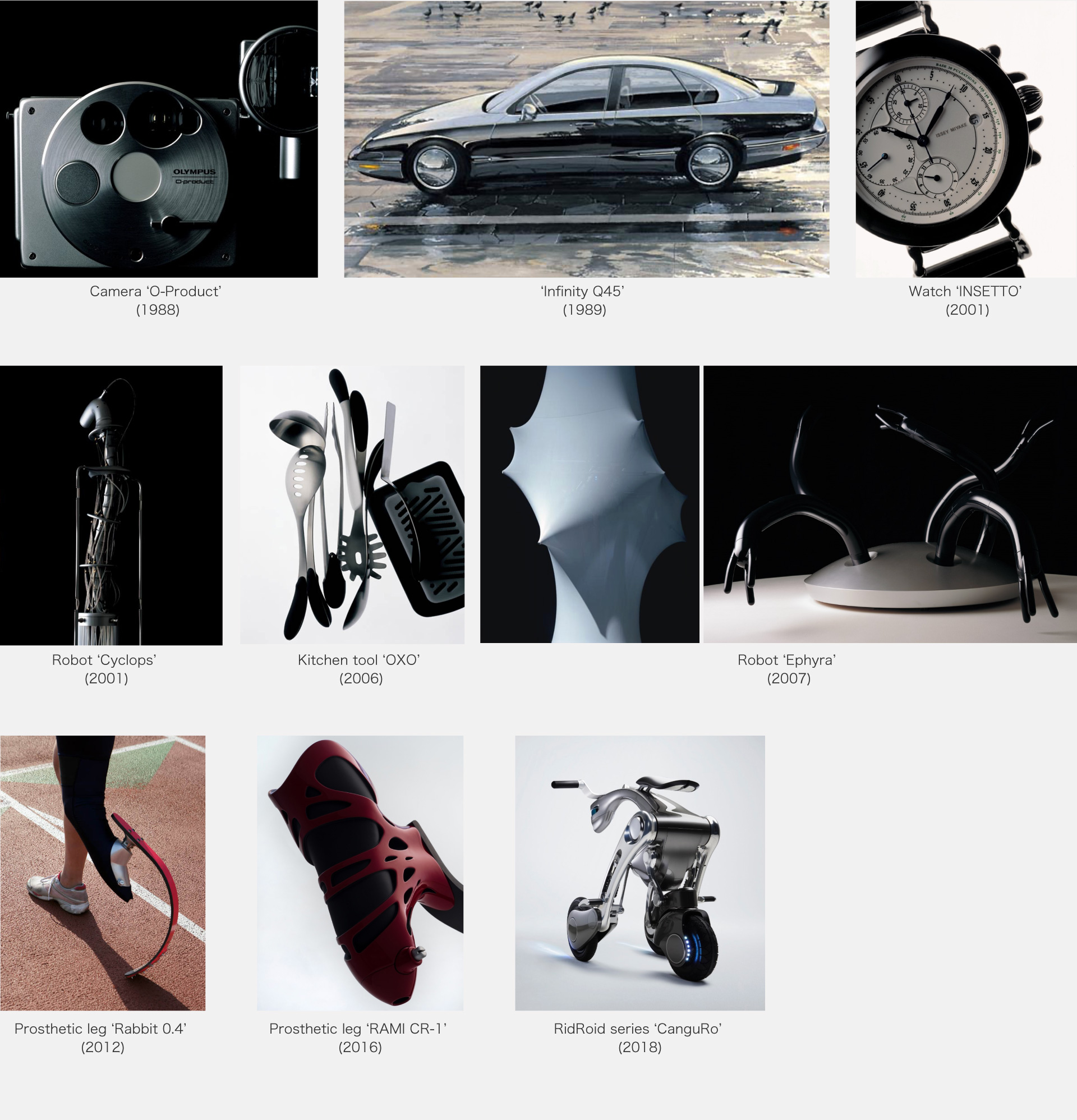

Yamanaka I think it was because I liked drawing ‘movement’, in other words, moving people and people playing sports. At the time, I loved the works of Shinji Mizushima, known for ”Dokaben”, and I wanted to draw the movement and dynamism of people doing sports, and later on I saw “Slam Dang” by Takehiko Inoue and thought that this was what I wanted to draw. I started out as a change of pace, but eventually I joined a club called “Todai Manga Club”, and being encouraged by my friends, I got more and more into it, and ended up staying in school twice. At one point, I was even seriously thinking about becoming a manga artist.

ー Why did you decide to pursue a career in design?

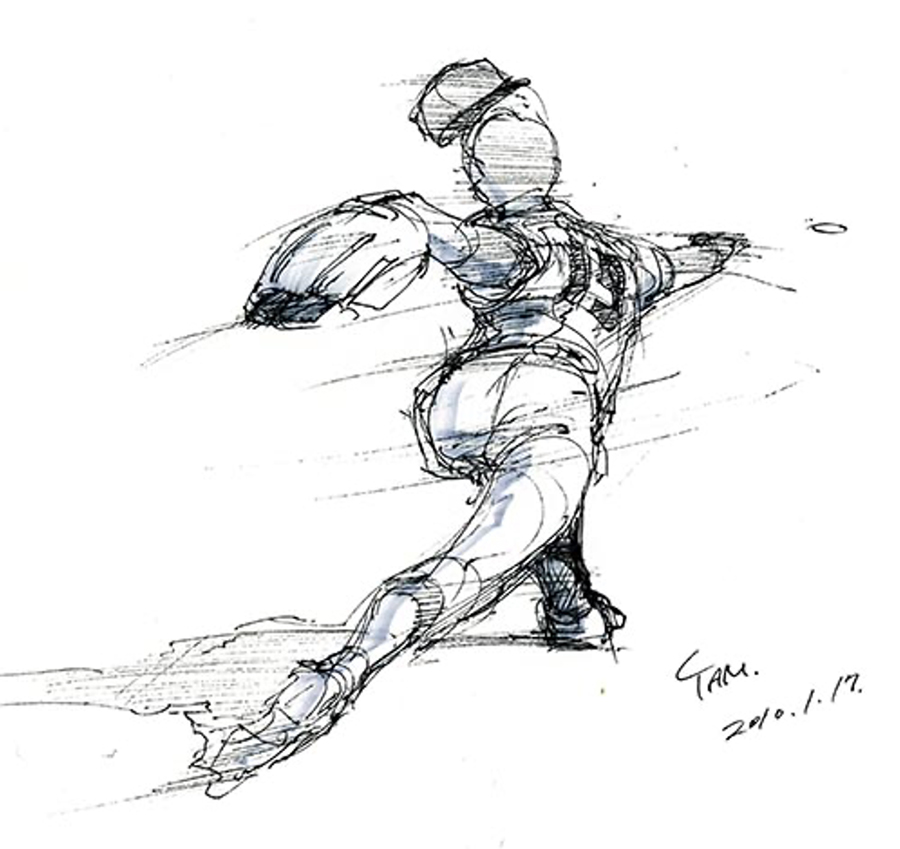

Yamanaka's dynamic sketches

Yamanaka The most important thing for a manga is to have an interesting story, but I like drawing pictures, and I wasn't really into creating stories. I thought this would be fatal to becoming a manga artist. I was attracted to the dynamism of human movement and the mechanisms of the human body, which is also why I chose mechanical engineering.

When I was in my third year at university, I considered architecture as a major, but I chose the Vehicle Engineering Laboratory in the Department of Mechanical Engineering because I felt that I was more suited to moving objects than static ones. It seemed like a job where I could make use of my cartooning expressiveness and my knowledge of mechanical engineering.

Becoming a car designer at Nissan Motor

ー I understand why you chose car design. Why did you join Nissan Motor?

Yamanaka When I told my then supervisor, Professor Masakazu Iguchi, that I wanted to become a car designer, he introduced me to Norihiko Mori, who was the head of the design studio, saying that Nissan Motor had a designer from the University of Tokyo. After studying applied physics at the University of Tokyo, he joined Prince Motor (which later merged with Nissan) and studied design at the Ulm School of Design in Germany, where he headed the design department. For me, Mori's influence on me is very significant, as he is the mentor who paved the way for me to become a designer and taught me the basics of design and what design is all about.

That Mr. Mori meant it as career advice, but I told him I wanted him to hire me as a designer. Two weeks later, I went to the company with a manga I had drawn as a student and a picture of a car I had drawn for a presentation. On the day of the consultation, he and two designers came to see me and said that the car drawings were no good, but the cartoon's dynamism was good. One day, about a month later, Professor Iguchi told me, ‘Nissan wants to hire you as a designer’. I was told that Nissan wanted to hire you as a designer.

ー You took the first step towards becoming a designer at Nissan.

Yamanaka My peers and seniors were all from art universities and good at drawing, so at first I imitated them and drew a lot of pictures. For designers, pictures are words, a language, so I needed them to convey my ideas and thoughts. Sketching in car design is particularly unique, so I studied techniques such as how to draw lively pictures in a short time, how to take compositions and how to draw reflections. I was also taught from scratch how to make models from clay, called industrial clay. I feel that I was thoroughly trained in the basics of industrial sculpture, such as the unique aesthetics of cars, taut curved surfaces, the flow of highlights, how to balance visual weight and how to overcome the collapse of details caused by the gap between image and manufacturing techniques.

ー At the time, there was a famous design school in Los Angeles, USA, called the Art Centre College of Design (ACCD), and many Japanese car designers were graduates from there, weren't they?

Yamanaka Yes, Japanese car design was influenced by ACCD, and in the 1980s car design was the flower of industrial design and attracted some of the best art college graduates. It was a time when the Japanese automobile industry was expanding into the global market and the design scene was full of vitality, with famous designers from all over the world coming to Japan to design Japanese cars. I was really lucky to be able to learn cutting-edge styling in such an environment.

ー It was a blessed environment, wasn't it?

Yamanaka I think so. But on the other hand, I also began to wonder whether styling alone was enough. I said that when I read the development stories of passenger cars, it was people like Ettore Bugatti and Paolo Pininfarina who impressed me because they were both engineers and designers. But in large companies, the division of labour was progressing, and I began to wonder if this was the right way for designers to work, who were only refining the styling.

ー You had a different perspective and approach to design from those who had studied at art college, didn't you?

Yamanaka When I discussed the car's design concepts and details with people from the product planning and body design departments, I was able to understand their arguments because I had an engineering background. So, I accepted their rationale. When I tried to find a reasonable compromise with them, my seniors warned me not to say anything unnecessary and not to compromise easily.

Every time I was scolded by my seniors, I felt a sense of discomfort, thinking, "Did this mean I should fight?" Another thing was that at Nissan, in order to realise my own design, I have to win an internal competition. Therefore, there were people who were dedicated to ‘designing to win the competition’. Well, maybe I got tired of such competition.

ー But did you also gain a lot from Nissan?

Yamanaka Nissan picked me up because I had never studied design before, and I was lucky to learn car styling from the ground up there. People say that my designs are organic and have a sense of life, but I thought that was something I gained from car design as industrial sculpture. My experience at Nissan was invaluable to me, and it supports me today. Still, there was a feeling somewhere that this was not the design I aspired to. When I finished the final production clay model of the ‘Infiniti Q45’, I thought that was the end of it.

ー I'm surprised that you were a company employee for five years (laughs).

Yamanaka That's true. But in fact, he was a pretty bad employee, and when he quit, he told me that it was hard to use him as an employee (laughs).

ー And you took your first steps as a freelancer.

Yamanaka It was around that time that I came across AXIS, and I wrote manuscripts for “AXIS” magazine, had a series of articles called “Technology Visualisation” and participated in planned exhibitions. The first time you met you was, I believe, for an interview for an advertisement for Apple Computer in “AXIS” magazine, wasn't it?

ー You talked about designing cars using Mac II and Illustrator 88.

Yamanaka There was a reaction because there were still very few people designing industrial products in Illustrator.

The two people who guided Shunji Yamanaka.

ー When I read the book “You Too Can Design”, I thought that for you, encounters with people were of great significance. In Yamanaka's case, it was a catalyst for him to take a leap into a completely new field.

Yamanaka My first encounter was with Norihiko Mori, as I mentioned earlier. The people and environment that I met when I became a freelancer had a particularly big influence on me.

ー Can you tell us more specifically about the people you met?

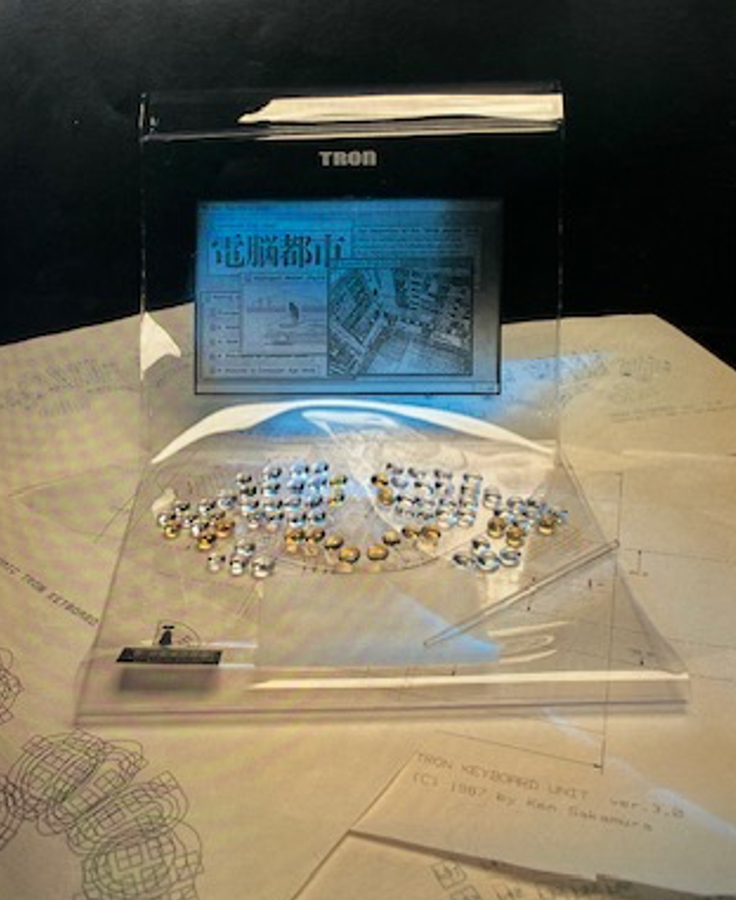

Yamanaka Around the time I quit Nissan, a classmate who I used to draw manga with introduced me to Ken Sakamura, a professor at the University of Tokyo and leader of the ‘TRON Project’(*1). He was designing not only the TRON general-purpose OS, but also various TRON-based products. I participated in the project as a designer and helped with various things, such as keyboards, computers and den-no-housing.

*1 A joint industry-academic computer architecture development project initiated in 1984 by Ken Sakamura and others. It is currently used as an embedded OS in automobile engine control, communications equipment and information appliances.

ー The TRON project was a big topic at the time. I remember that it was an idea that was a precursor to what is now known as the IoT (Internet of Things).

Yamanaka TRON was an embedded OS, so it was suitable for home appliances and mobile phones, and for a while it held a large share of the Japanese product market. It did not expand globally like Windows or iOS in the face of international competition, but I think it was very pioneering and an important turning point in the history of Japanese technology.

In the late 80s, there were no mobile phones, let alone smartphones, but the project team talked about the future, including them. For example, in the future, everyone would have a portable calling device, like a Walkman, and they would be able to call directly to a person's name. I drew a picture of me carrying something like a stick in the future, where I could use my computer anywhere wirelessly, connected to all kinds of appliances and cars. It's amazing that most of the futuristic visions I envisioned at the time came true 20 years later.

ー Mr Sakamura made a model of a computer for “AXIS” magazine that was transparent, thin like a handkerchief and can be rolled up into a ball.

Yamanaka Actually, that was my handmade model. He and his research team told me about their idea, and I created a concept model of a transparent and flexible notebook PC using acrylic and glass that I bought at Tokyu Hands. His conceptual ability and energy to create prototypes of technologies under development and to involve many people in creating the future in concrete ways was wonderful. I think I learnt how to draw the future from him.

TRON's future computer in AXIS No. 26 (Winter 1988), designed by Ken Sakamura, mock-up by Shunji Yamanaka

ー This is where Yamanaka's design starting point of ‘envisioning the future with technologies currently under development.’ was nurtured. Who else has influenced you?

Yamanaka Naoki Sakai, a conceptor. Mr Sakai, who has fashion design as his foundation, was skilled in sensitivity marketing. Based on the fantasy of ‘wouldn't it be nice to have something like this’, he first constructed a world view that assumes branding, and then designed products as belonging to that world view. This was a completely different approach to that of the technology-orientated Mr Sakamura.

ー What exactly was your approach?

Yamanaka First, we visualised concept words and concept photos based on our personal sensibilities as a collective and created an image board. All the members shared this worldview and sketched it out, incorporating it into concrete designs in terms of shape, colour and materials. For me, the process was fresh and satisfying, as if a new world had suddenly opened up. He was the person who taught me how to construct the world view behind a product based on an aesthetic sense.

ー You were lucky to meet two contrasting people - technology-driven and romance-driven.

Yamanaka My encounters with both of you are the two wheels of my manufacturing. Mr Sakamura set the technical goals before proceeding with the design, while Mr Sakai worked out the style before thinking about how to make the product... They had completely opposite approaches. But because I was able to experience both, I came to believe that the best work was to explore the point of contact between the two.

ー What would you say are your representative works from this period?

Yamanaka As for commercialised products, the Olympus ‘O-Product’ and ‘Ecru’ cameras that I made with Mr Sakai. The TRON project was mostly prototypes, but the ‘μB-TRON (PC)’ appeared as the main machine in the NHK programme series, and the Cyber House built in Roppongi.

ー The Cyber House was actually visited. It was a house where you could experience the ubiquitous computing that we now take for granted, and I learnt for the first time that you had designed the TRON prototype.

Yamanaka In the media at the time, Mr Sakamura and Mr Sakai were introduced at the front, and I was behind the scenes (laughs). But the two of you gave me, an unknown newcomer, a place to make things, and I am sincerely grateful to you.

ー It was precisely because you were not a ‘me, me, me’ person that there was no end to the number of people who wanted to work with you.

The University of Tokyo and the JR project.

ー What people or things have had an impact on you since then?

Yamanaka In 1992, I was invited by the University of Tokyo to be a visiting assistant professor in the JR Endowed Chair by Professor Iguchi. He was a benefactor who placed me, who was only drawing manga, in his laboratory and connected me to Nissan. He approached me about a joint project between the University of Tokyo and JR, saying that it was important to develop human-centred technology. The project lasted three and a half years, but I was involved in the development of experimental vehicles such as the ‘TRY-Z’, with the goal of ‘realising an ideal railway system for the 21st century’.

ー According to your blog, "I designed a train called ‘TRY-Z’ in 1994. We conducted a series of studies on how the driver's cab should be designed to operate conventional railways safely at high speed on ordinary tracks, with the participation of engineers from JR East and vehicle manufacturers, as well as veteran drivers and cognitive scientists".

Yamanaka This led to the development of ‘Suica’.

ー ‘Suica’ is Yamanaka's best-known work.

Yamanaka Suica became the prototype for Japan's IC boarding system, but at first it was only a small-scale experiment. I was approached in 1996, when JR East was preparing to experiment with a new ticket gate using Sony's proximity communication system. I first suggested that they give variations in the shape of the prototype reader/writer, which would be the heart of Suica, to the general public to try out and see how easy it was to use.

ー What were the results?

Yamanaka As a result of making and testing five types of prototypes, we found that the smoothest way was to tilt the body of the reader-writer slightly towards the front to emit light. In the end, it was decided to raise the reader-writer by about 13 degrees to the extent that it would not interfere with the passage of people. Later, when we discussed the intellectual property rights to this idea, we licensed it to railway companies all over Japan, as it was important that it could be used in common throughout the country. It was a time when the term “usability engineering” had not yet been coined in Japan, so I thought we had done well. It became the starting point for the idea that experimentation and observation are important in usability design, and that design should not be based solely on the designer's sensibilities.

The heart of ‘Suica’, five different prototype reader-writers for experimental use.

ー The development of Suica was a project to “envision the future with technology under development”.

Yamanaka You were able to participate in the project from the early stages of technological development, perhaps because your usability engineering practice of TRY-Z, in which you participated as an assistant professor at the University of Tokyo, was highly valued.

ー You took on a job for which you might not have found an answer.

Yamanaka In fact, when I undertook this experimental project, I was half-convinced that it would succeed, but as a result, I was told that it had triggered the spread of IC cards, which is said to be a five-trillion-yen market. I don't think I would have taken on this job if I had been a 20th century designer who gave styling to a completed technology.

A fusion of ‘technology’ and ‘romance’.

ー The term ‘20th century designer’ is a stimulating one. Yamanaka's ‘prototyping’ is a concept that anticipates 21st century design. It was important to incorporate the concept of ‘beauty’ into it. It is.

Yamanaka The point is how to fuse the ‘exploration of technology’ and the ‘romance of styling’, but it is difficult to do so because the two are diametrically opposed in their approach. Thinking objectively/logically based on data and evidence to predict the future and thinking subjectively to derive shapes and worldviews from our inner self are completely different ways of using our brain. So I am conscious of using these two methods differently.

For example, the ‘INSETTO’ watch is designed more like art, with an emphasis on poetic story and styling rather than technical factors. The kitchen goods ‘OXO’ and ‘Suica’ were usability engineering approaches derived from thorough experimentation and observation. The two are different in terms of both the intended users and the effects. Maybe this is why my work looks so disjointed at first glance.

ー In the current context, what is the position of robot design for you?

Yamanaka Paradoxically, humanoid robots are precisely at the interface between the two. The first robot I worked on, ‘Cyclops’, was intended to be displayed at an exhibition, so I didn't have a user in mind, but rather purely expressed my own thoughts, such as how it would be a magical space if there were such a thing, or how exciting it would be if it moved like this. It is a work of art that makes full use of cutting-edge technology.

ー For you, robots seem to have something in common with manga in that you ‘value romance’.

Yamanaka It's quite close, isn't it? I start by imagining a world within myself, a fantasy where such things exist and move in such ways. Regarding robot construction, Mr Takayuki Furuta (currently Director of the Future Robotics Technology Research Centre at Chiba Institute of Technology) is also a crucial partner. I met him in 2001, immediately after creating 'Cyclops'. He asked for my cooperation in developing a small humanoid robot he was conceptualising. He is an engineer with a very strong aesthetic sense, and we immediately hit it off. We progressed the design by exchanging a single drawing multiple times between us. The result was 'morph 3'. Subsequently, we collaborated on prototypes for various robotic vehicles, such as 'Halluc II' and 'CanguRo', which also led to the development of Panasonic's robotic vacuum cleaner 'Rulo' in 2021.

ー At the “Future Elements” exhibition at 21_21 DESIGN SIGHT, there was a fun video showing a big march of robots designed by you. You launched the watches ‘INSETTO’ and ‘OVO’ from ISSEY MIYAKE. What was Issey Miyake like for you, who was involved in both the conception of the museum and the development of the watch series?

“Future Elements” exhibition (29 Mar - 8 Sept 2024, 21_21DESIGN SIGHT). The exhibition was exactly what its subtitle, “A laboratory of science and design”, implied. Photos/Seki

Yamanaka I met Mr Miyake around 2000 at an exhibition in the MDS Gallery, which was the information dissemination base of the Miyake Design Office. He was very interested when I showed him the prototype of the ‘Tagtype’ keyboard that I had made with Kinya Tagawa. Later, he came to the Tagtype presentation, and when I showed him my portfolio, he was interested in the ‘INSETTO’ I had designed for Seiko. It was originally a proposal for a high-function watch with insect details overlaid on a precision mechanical structure around 1990, but unfortunately the project was not commercialised. A month later, the Miyake Design Office approached me about commercialising the project, and Seiko readily agreed, and INSETTO was awakened from its 10-year slumber.

ー What kind of influence did he have on you?

Yamanaka He was a person who acted purely on what he was interested in. There was an impressive episode. When we were discussing commercialisation with Seiko representatives in the presence of Midori Kitamura (Now chairman of the Miyake Design Office), Seiko asked us to compromise on manufacturing technology. When I listened quietly, Ms Kitamura suddenly said, "Are you sure about that? I was on the verge of compromising myself, but she gave me a strong warning. After I became independent, I also made an effort to keep thinking, but Mr Miyake made me realise the importance of this again.

ー Engineering and scicence can be explained and proved with numbers, but sensibility and romance cannot. That is one of the weak points of designers, isn't it?

Yamanaka That's right. When someone logically and empirically explains function, structure, manufacturing technology, etc., designer can only say ‘I somehow feel it's different’ about sensory values, which is difficult to persuade, so they tend to take a defensive and hard-line stance. Of course, beliefs and aesthetics are just as important as engineering performance, as they play a role in the performance that affects people's psychology. It is not good to be biased towards one or the other, nor is it good to compromise. I think this is the position I have been exploring as a designer.

ー What about now?

Yamanaka Right now, I feel that I am able to break through seemingly contradictory things with ideas while having fun. Ideally, science, design, engineering and romance should coexist in one person. I've collaborated with a lot of different experts over the years, but there's definitely a place where I have to be someone who enjoys both worlds to go.

The intersection of biology and machines.

ー Your product designs have a biomimetic impression.

Yamanaka The mechanisms and movements of living organisms are very important research subjects. In my exhibition robots such as ‘Cyclops’ and ‘Ephyra’, I was very conscious of the movements of living organisms. Ordinary robots tend to have jerky movements due to control latency and mechanical backlash. If they are made very precisely and controlled well, they can move smoothly, but people and living creatures are not so precise. When they stop or change their movements, they waver or get lost. We designed the robot with the idea that we could incorporate that smooth looseness into the robot.

ー I agree. People's sensibilities are very sensitive about what is natural or not.

Yamanaka The shapes produced by mechanical engineering are born from the translation of natural phenomena into geometry and mathematical formulae, and are fundamentally different from the optimum (in a sense, ad hoc) shapes that living organisms have acquired in the process of evolution. Since the human aesthetic sense is acquired during the process of human evolution, many of the forms, movements and appearances that we find beautiful are derived from natural objects. In ‘INSETTO’ and ‘Cyclops’, I was conscious of superimposing the beauty of machines on the beauty of natural objects.

ー In terms of the interface between living beings and machines, what about the prosthetic leg designs you have been working on for many years?

Yamanaka It is a natural desire of people who have lost a limb to get closer to the shape of the lost human body, whether it is a prosthetic leg or hand, and there are prosthetic arms and legs that look exactly like the real thing. But I dare not even take that approach and look for the shape of a mechanical component that works efficiently as part of the human body and does not resemble a human leg. Because the energies, structures and materials that can be successfully handled in engineering are so different from those in nature. So it is fundamentally different from the bio-mechanical approach. But in life, we want artificial objects like clothes and shoes to follow the flow of the human body. That is why prosthetic feet are designed to have an organic shape that fits the human body, but does not resemble a human foot. I think this was a very good case study in terms of design where natural and artificial objects are in harmony.

ー Of all your prosthetic leg projects, Saki Takakuwa's prosthetic leg is one of the best known.

Yamanaka I first became interested in prosthetic leg design at the Beijing Paralympics in 2008, when I was fascinated by the sight of athletes running at full speed wearing plate spring prosthetic legs. It was around that time that I was introduced to high school student Saki Takakuwa by prosthetist Fumio Usui, who organises a club for athletes with prosthetic legs.

She had only lost her leg for about two years and had just started running, but she agreed with my idea and said she wanted to wear cool prosthetic legs too. She later entered Keio University and became a member of my laboratory, and with the help of Mr Usui, we completed the ‘Rabbit 4.0’ prosthetic foot for athletes four years later. In the meantime, she grew up as an athlete, became a Japanese record holder and won national and international competitions with the prosthetic leg we designed. The ‘Rabbit 4.0’ was not only functional, but also ‘cute’ and ‘fashionable’ and became a topic of conversation, leading to a change in social attitudes towards prosthetic limbs. For me, the design of prosthetic legs and hands is more about creating a new body than complementing a lost body, which is why I aimed to create ‘beautiful prosthetic legs’.

In 2013, I moved from Keio University to the University of Tokyo, where I met Professor Toshiki Niino, who was researching 3D printers, and took my work to a new level. Besides Ms Takakuwa, a number of people came to me asking for a beautiful prosthetic leg, but I couldn't meet the demands of many amputees with one-off handmade products. Professor Niino and we have developed a CAD system specifically for prosthetic feet and have succeeded in producing them efficiently using a 3D printer, making it possible to supply prosthetic feet for several athletes from 2019 onwards.

ー Did you consciously get involved in the development of one-off items that are not mass-produced, such as robots and prosthetic legs?

Yamanaka The keyboard ‘Tagtype’ was the inspiration for this project. 1998, Kinya Tagawa, a fourth-year student at the University of Tokyo who was working part-time in my office, asked me if I could make a two-handed thumb Japanese input device for a disabled friend of his who was a writer. He devised an input method called ‘Tagtype’, which uses only the thumbs of both hands to input Japanese, as his thesis at the University of Tokyo. I was impressed, and together with him and his friend Jun Honma, a software designer, we produced several working prototypes. Although we were unable to mass-produce the prototypes, they were featured in various media and TV programmes, and in 2009 MoMA (Museum of Modern Art, New York) selected the prototypes for its permanent collection, and they are on display.

I have been consciously working on one-off products such as the ‘Tagtype’, prosthetic legs and hands, and robots, which are not necessarily intended for mass production. This is because unlike industrial design, which is based on mass production, I do not expect immediate profit, but I think it is a very important activity to present my vision to society and to be recognised. I think it can be said that meeting them paved the way for the development of one-of-a-kind products.

Tagtype could not be mass-produced, but it was selected for MoMA's permanent collection. Jointly developed by Kinya Tagawa, Jun Honma and Yamanaka.

ー What would you say is the attraction of one-off design?

Yamanaka One-offs are more of a work of art and may be more like art than design. Is it art that makes full use of engineering?

ー From a historical perspective, I feel that one-off design is recorded as an epoch and left in people's memories more than mass industrial design.

Yamanaka If that's the case, I think the influence of the times is also significant. Since the makers' boom, it has become very significant to transmit what individuals have created on social networking sites. The internet has become commonplace, and it has become easier to learn about and vicariously experience individual craftsmanship. ‘Tagtype’ and ‘Cyclops’ may have been a precursor to this era.

Design before and after digital, and in the age of AI

ー Your generation has lived in parallel with the reality of the rapid digitisation of design. What are your views on design before and after digitalisation, and in the age of AI?

Yamanaka The Nissan design site where I took my first steps as a designer had a thoroughly classical style. So there was very little digital in the process from sketches, drawings to clay models. But learning those handmade skills at Nissan was an asset for me. Because of that, I was able to design while moving back and forth between the two in the process of replacing them with digital.

So I feel that our generation worked while studying how to replace analogue sensibilities with digital ones.

ー In his book, “You Too Can Design” , you teaches high school students the first steps of design in a workshop format. You dares to teach in the classic way of making mock-ups from hand-drawn sketches and analogue materials. Is this because you emphasise physical expressive habits and sensations?

Yamanaka I think the digital is equally important. In a text I compiled for an old “AXIS” magazine called ‘User Friendliness’, I wrote: "I want design tools to be more like something that can be experienced at the sketching stage. I would be happy to see such a future where sketches can move as they are”.

ー That was the ‘virtual running prototype’ in the text, wasn't it?

Yamanaka In the early 1990s, technology was still in its infancy, so there was a muddled mixture of analogue and digital things that could and could not be done. For example, no matter how beautiful a car model you make in clay, you can't actually open the doors. I felt that was very unfortunate for designers. When new tools came out, I was trying them out one by one. Nowadays, that would be AI.

ー Can people who can draw clean lines and have a good three-dimensional sense in the real world also design clean lines and beautiful volumes in the virtual world? So handmade skills are important.

Yamanaka I think that is a very important part. Very important. That is exactly what AI lacks today, and when you let AI design, you are not impressed when you actually make something. Not long ago, a photographer said, "The photos are good because AI was used by photographers who know how to take good photos. It doesn't mean that everyone can do it if they use AI". At the moment he is right, AI is still a tool.

ー Will design change when the digital native generation becomes mainstream?

Yamanaka I understand that digital natives feel that it is faster to draw on a computer from the beginning rather than on paper, and I think this is a natural thing. What will happen to the aesthetic sense of digital natives? Even if you look at ‘future maps’ of the past, they may have been technically correct, but the designs only look old-fashioned. Is that the limitation of predicting the future of design.

About the design archive

ー Now, I would like to ask you about your design archive. What is the current status of your past works, their data and materials?

Yamanaka Right now, I am in the middle of thinking about what to do. I'm currently pondering what to do with it. This building (Building S, Institute of Industrial Science, the University of Tokyo) has been renovated as the 60th Anniversary Hall and is now an exhibition space for cutting-edge technologies and projects up to the present day.

ー (Moving to the exhibition gallery) In the gallery, many of Yamanaka's projects are on display, giving the impression that it is truly a collection or archive of your work. Do you mean that these will become part of the archive of the University of Tokyo in the future?

Yamanaka We will have to coordinate this with the University of Tokyo. It is certain that the current exhibition occupies a large space for the results of the Foundation for the Promotion of Value Creation Design, including my work, but the future is not guaranteed.

ー The whole gallery has a design mindset, is this due to Yamanaka's influence?

Yamanaka When I was invited to the University of Tokyo 12 years ago, a group of professors came up with the idea of fusing design and engineering/science in research and human resource development, and this is the result of our work together. One of these colleagues is Teruo Fujii, the current President of the University of Tokyo. Preparations are now underway, led by him, to open a new faculty called the ‘College of Design’ in 2027.

ー Do most of the people who studied in Yamanaka's lab go into design?

Yamanaka There are both engineers and designers - Shohei Takei, the head of ‘nomena’, who won the Mainichi Design Award 2024, is one of my dear friends, and many of his staff came from my lab. There are many other freelance designers and design thinking business entrepreneurs, and I sometimes call on them to help me with big projects.

ー What is the current status of Leading Edge Design (LED) works and materials?

Yamanaka What are we really going to do about LED-related issues? We are in a state of uncertainty. For the time being, we are organising our website and looking for a place to consolidate all the scattered works in one place. The individual products are dispersed, but they are all stored and ready to respond to exhibition requests.

ー I really hope that your work will be passed on to future generations.

Yamanaka Yes, that's right. Not only the products, but also the development process and the engineering background.

ー What do you think about design museums and design archives in Japan?

Yamanaka There are many things I have learnt from actually touching things, so I think it is absolutely necessary to have a place where people can see and touch actual products. I learnt from the prototypes of overseas designers stored at Nissan, Issey Miyake's Shiro Kuramata collection and the Dyson prototype exhibition. Also, when I go abroad and visit the Design Museum in London or MoMA in New York, I regret that they are not in Japan.

ー Is it because industrial design in particular has the fate that when technology becomes old, the products also disappear, making it difficult to collect them?

Yamanaka Yes, that's right. Our engineering and IT-related design is ephemeral.

ー Do you think it is necessary to have collections as “objects”, too?

Yamanaka People nowadays, when they see a beautiful CRT TV in a museum, just wonder why it's so big. So I wonder if there is really any point in exhibiting them. But if they are moved by its formative beauty, it might have some kind of impact on them. I myself have learnt a lot from old things.

ー What kind of things do you learn from them?

Yamanaka For example, the masterpiece cameras of the past have a beautiful geometric structure in which the lens and various other components are arranged around the optical axis, because this is what makes them culturally camera-like. I design with respect to that. Both ‘O-product’, my first design as a freelancer, and ‘Clockoid’, a clock-themed robot I created in 2018, were born from rethinking the history of products. I recognise that design museums are very important. But we need money to start anything, but we don't know where to approach, who to approach and how to approach them.

ー The University of Tokyo has a large archive, doesn't it?

Yamanaka There is the University Museum of the University of Tokyo. The exhibits were collected by Yoshiaki Nishino (specially-appointed professor at the Museum of General Studies and director of IntermediaTech), who collected information on valuable materials and specimens that would otherwise be discarded from all over the University of Tokyo and actually saw them, which requires a tremendous amount of time and effort. It is essential that someone vigorously collects and organises them.

Don’t Limit Yourself

ー Finally, what you would like to say to designers and designers.

Yamanaka These days I try to call myself a design engineer or something, but actually I try to be indifferent to the fact that I am something. There is a deep awareness of the issues involved.

ー Problematic?

Yamanaka Modernity is based on the premise of a social structure made up of a group of specialists. Companies and universities are subdivided into detailed areas of expertise, and are based on the idea that good results should be produced if experts in each area do a good job. My problem is that I think this is a mistake.

ー It is true that everything is becoming more fragmented and complex, and it is difficult to be free.

Yamanaka I believe that designers should be specialists in the broad sense of ‘this is what I want’ and ‘this is what I want to do’. Of course, the power of segmented specialists is necessary, but I would like designers to try to move freely beyond those boundaries.

At present, it is commonplace in society for a small number of people to decide what to create and what to do, and for most individuals to become small cogs in a fragmented and specialised field. But I don't want designers to be like that. What I want to say to young people is, ‘Don't tie yourself down to some expert’, and I want society to respect such people.

ー I thought at the beginning today that you are a person who wants to move without settling yourself down. You have a challenging and eternal amateur mindset, or something like that.

Yamanaka That's right. I've already been a professor at the University of Tokyo for 12 years and I'm thinking inside that it might be bad. I've been talking to my wife about it, and I'm thinking that when I went freelance, moving to a new house or office and changing the way I worked led to meeting people and job opportunities. When I incorporated LED in 1994 and started my design activities in earnest, my wife and I would draw manga together when we found time. I was drawing cartoons with my wife when we found the time. She and I have been working together ever since we met at the Manga Club at the University of Tokyo. The cartoons I drew then have not yet been published, but I hope they will see the light of day one day (laughs). In fact, I've been drawing some of them recently.

ー Starts and ends with a manga? (laughs). I would like to hear more about what you have to say, but thank you very much. And Shunji Yamanaka's archive, please make it happen.

Location of Shunji Yamanaka's archives and contact information

Shunji Yamanaka Laboratory, Institute of Industrial Science, University of Tokyo

http://www.design-lab.iis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/

Leading Edge Design

https://www.lleedd.com/

Shunji Yamanaka's archive site (under construction)

https://www.shunjiyamanaka.com/