Japanese Design Archive Survey

DESIGN ARCHIVE

Designers & Creators

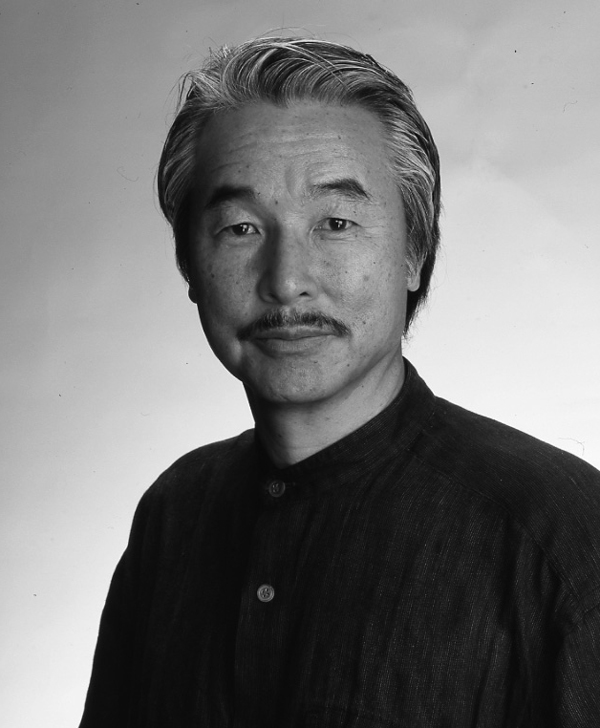

Ryohei Kojima

Graphic designer

Interview 01: June 29, 2020 13:00 - 14:30

Interview 02: July 8, 2020 13:30 - 15:00

PROFILE

Profile

Ryohei Kojima

Graphic designer

1939 Born in Iwate Prefecture

1960 Graduated from Musashino Art University Junior College of Art and Design, Department of Commercial Design, and joined San-Ai Advertising Department

1963 Joined Light Publicity Co.,Ltd.

1976 Established Ryohei Kojima Design Office

2009 Passed away

Description

Description

The period from the late 1960s to the 1990s, when Ryohei Kojima was active in the Japanese design world, was a time when many talents blossomed at once, as if in step with economic growth. The graphic design world, in particular, must have had many opportunities to work on national projects such as the Olympics and Japan World Exposition, Osaka, as well as the rapidly expanding advertising and publicity media and the rush to publish new magazines. In addition to the heavyweights who had led the postwar graphic design world, such as Yusaku Kamekura, Kazumasa Nagai, Ikko Tanaka, and Kiyoshi Awazu, there was competition among young and unique artists such as Eiko Ishioka, Masuteru Aoba, Katsumi Asaba, and Makoto Matsunaga. Ryohei Kojima was one of these young designers, and through his work in advertising, CI, and art direction for major corporations such as Isetan and Kikkoman, as well as for leading magazines such as "Mrs.", he embodied in graphic form the vibrant mood of Japan.

Kojima seems to have learned a lot from Herbert Bayer, an Austrian-born designer who also participated in the Bauhaus, and indeed, his designs, which are based on a clear composition and combine concise form with rich colours, confirm his idea that "I want to continue to pursue the creation of works that are simple and clear in colour and form, and that are easy for anyone to understand (from the website of Ginza Graphic Gallery) . Although Kojima worked on a wide variety of projects, his posters on the themes of wild birds, animals, and nature, which were his life's work, are the quintessence of Kojima's design, in which he wished to convey his feelings about the destruction of nature and wild animals not through words but through graphics. We spoke with Mrs.Yoshiko Kojima and their son Ryota, a graphic designer, about the current state of Kojima's work and design materials.

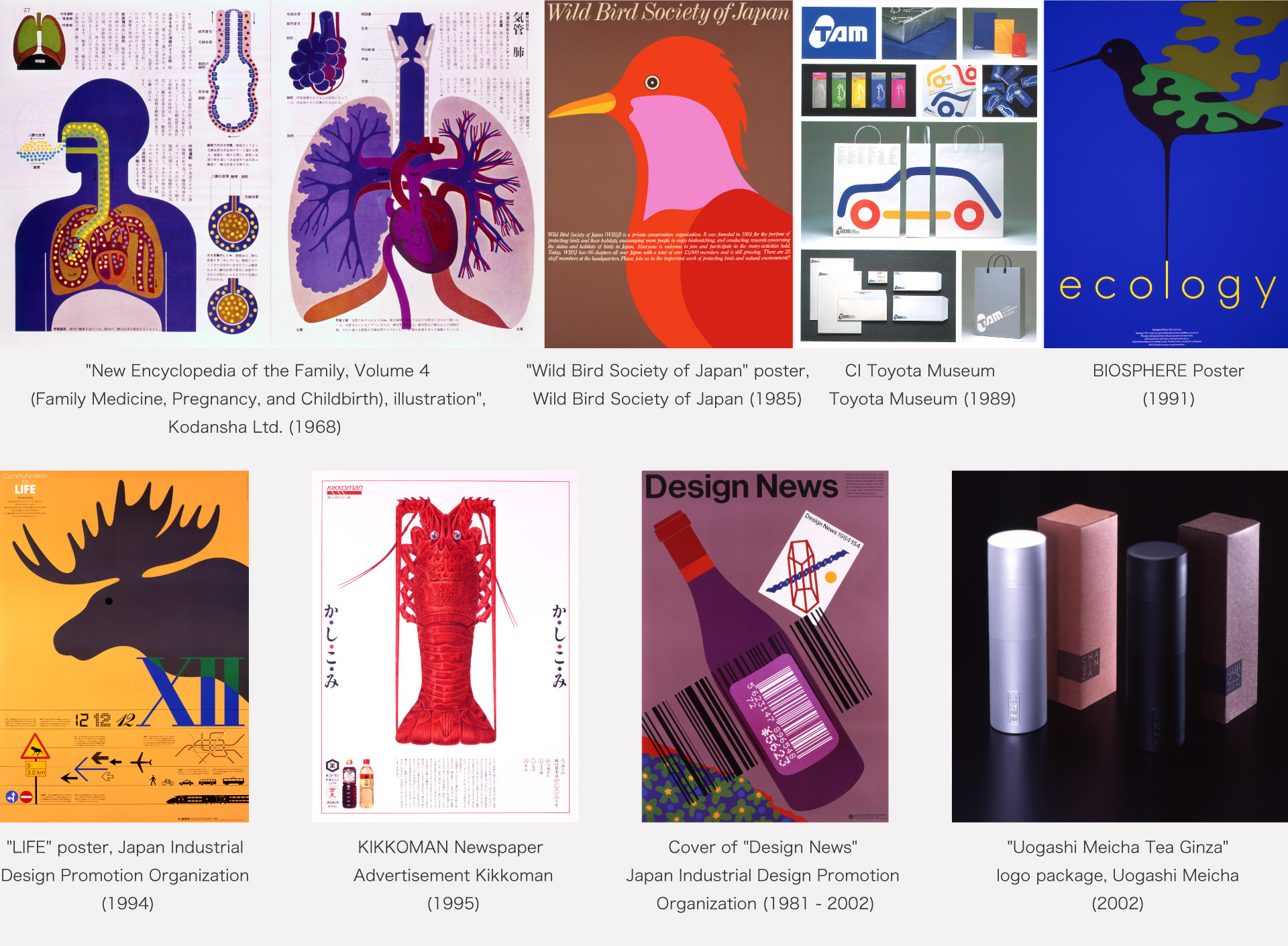

Masterpiece

Masterpiece representative works

Illustrations for "New Encyclopedia of Home, Volume 4 (Home Medicine, Pregnancy and Childbirth)" Kodansha (1968),

Isetan Image Poster (1973-),

"Wild Bird Society of Japan" Wild Bird Society of Japan (1985),

CI of the Toyota Museum Toyota Museum (1989),

BIOSPHERE Poster (1991),

"LIFE" poster, Japan Industrial Design Promotion Organization (1994),

KIKKOMAN newspaper advertisement, Kikkoman (1995),

Catalogue of the exhibition "Shiro Kuramata" Hara Museum of Contemporary Art (1996),

Cover of "Design News" Japan Industrial Design Promotion Organization (1981-2002),

Logo package for Uogashi Meicha Tea Ginza, Uogashi Meicha (2002)

Major Exhibitions

"K3 Exhibition", INAX Gallery, 1980; "FLAG Exhibition", TDS Gallery ,(1982)

"BIOSHERE Exhibition", TDS Gallery (1991)

"TROPIA GRAFICA Exhibition", Ginza Graphic Gallery (1993)

Main Books

"Graphic Design in the World 47: Ryohei Kojima", Ginza Graphic Gallery (1999)

"Visual Message Ryohei Kojima's Design World", Guangxi Art Publishing House (China, 2000)

Major Awards

Special Prize at the JAAC Exhibition, Tokyo ADC Award (1965); JAAC Encouragement Award (1966), Semi-Asahi Advertising Award (1972, 1973, 1974, 1975); Mainichi Advertising Design Award Special Prize and Japan Sign Design Award (1978); Mainichi Advertising Design Award Grand Prize (1980, 1987); Mainichi Advertising Design Award, Colour Advertising Award (1991, 1994); Nikkei Advertising Award, Excellence Award (1996), etc.

Interview 1

Interview 01: June 29, 2020 13:00 - 14:30

Location: The Westin Tokyo

Interviewee: Mrs.Yoshiko Kojima

Interviewers: Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

Interview: Yoshiko Kojima

A good balance between design and play.

The Current State of the Design Archive

― It has been ten years since the death of Mr. Ryohei Kojima. First of all, please tell us about the current status of Mr. Kojima's works and materials.

Yoshiko Kojima The staff of the office for generations had kept not only the works but also sketches, photographs and clear prints, but when Kojima passed away and we had to live in an apartment complex, we had to sort out the stock and unfortunately disposed of the paper bags and other three-dimensional objects.

― How did you decide what to keep and what to dispose of?

Yoshiko Our son (Ryota, a graphic designer) did the final selection, so please ask him about the details. However, he wanted to keep the photos as a record, so he asked a cameraman he knew to take digital photos.

― What are some of his works?

Yoshiko It's mainly posters, but I've kept some sketches and interesting prints. Musashino Art University has acquired most of his posters for their collection. Other collections include the Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art, the CCGA Center for Contemporary Graphic Arts at Dai Nippon Printing, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Reinhold Brown Gallery in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Municipal Museum of Amsterdam. The posters had many opportunities for exhibitions, and were often donated directly after they were finished.

― He was active in a wide range of fields, including corporate image advertising for Isetan and Kikkoman, visual design for the Toyota Museum of Art, logo and sign design for buildings, and art direction for "Mrs." and "High Fashion".

Yoshiko He used to say that advertising, logos, magazines, etc., are designed by the client, so he must have taken photographs and sorted out the actual products as a record.

― So, Ryota did the archiving for Kojima.

Yoshiko My son used to work with him as a staff member at Kojima Design Office, so we rearranged what had been left behind by previous generations of staff. It seems that Ryota supported him when he was unable to work on a PC, and after his death Ryota took over the firm. As I was not directly involved in Kojima's work, I was not sure how much I would be able to tell you today, so I have brought along the office catalogue for your reference.

― Thank you very much. So, Yoshiko, what is it about his archives that impresses you so much?

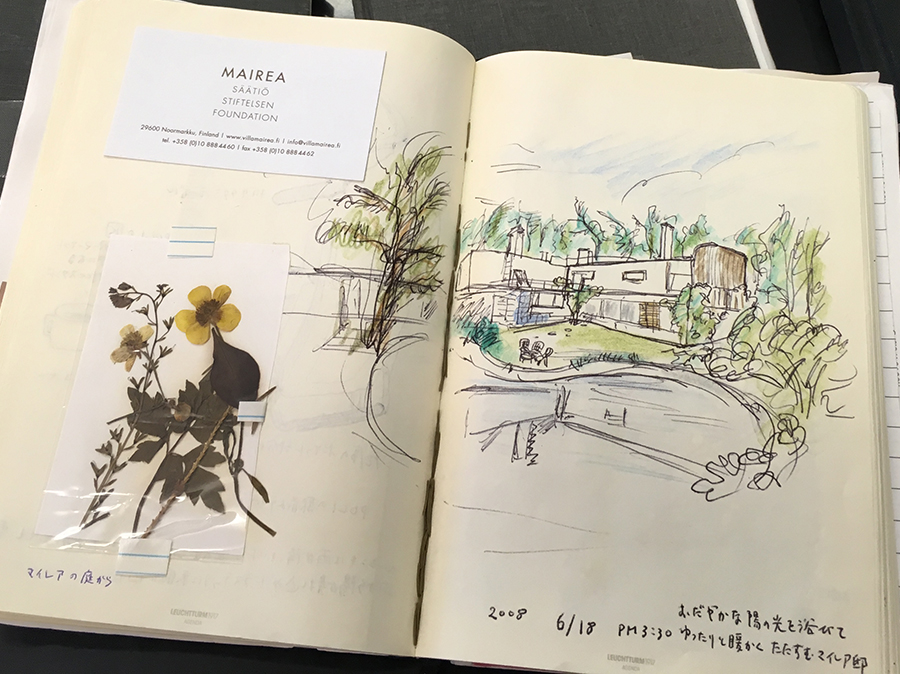

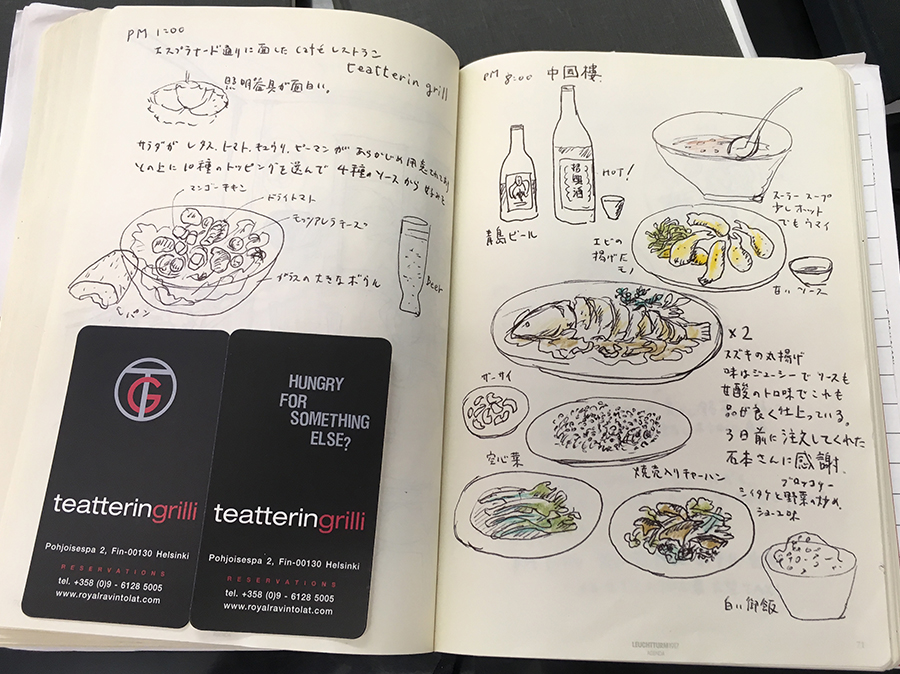

Yoshiko Kojima's sketches, which he made whenever and wherever he felt like it, and the colour samples, coloured pencils and scraps of coloured paper that he bought in foreign countries, as he was very particular about colour. I also have a notebook with sketches of his travels.

― Did those sketches include any design ideas?

Yoshiko His travel notebooks are not directly related to his work as they are his memories, but they are a kind of travel diary where he describe the food, the table, the ingredients, the architecture and the city. On his travels he would buy antiques, old toys and other items of his own choosing.

― It's exciting. In terms of his collection, what about his books?

Yoshiko We had a large collection of books, but I think we got rid of all the books except for the ones that Kojima himself liked. There used to be a bookstore called Tokodo that would come and sell books door-to-door every month, and he would buy not only magazine subscriptions, but also Western magazines and books that were hard to come by at the time, art books, photography books, and many other books. Unlike today, we didn't live in a society where you could find out anything on the Internet or social networking sites, so I guess they got a lot of information from books.

― What about the tools he used?

Yoshiko I have kept coloured pencils, compasses and pencils. He was a person who took good care of things, so he used Uni pencils and used them up until they became too short and then stored them in a can.

― As a wife, what was the most difficult part of the archiving process?

Yoshiko He was the kind of person who kept everything, even things from his school days, so he had a lot of stuff, and I didn't have any instructions about what he wanted to do with it, so organising it was really difficult.

― What are you doing with them now?

Yoshiko We store them in several different locations.

As a graphic designer

― I'll leave the details of the archive to Ryota, but I'd like to ask you about him as a designer. I remember that you also ran a gallery at the Kojima Design Office in Shirokanedai.

Yoshiko Yes. There was a space on the first floor of our office that was not being used, so we displayed Kojima's works. Some people were interested in it, so we thought I'd introduce other people's works as well, and that's how it started.

― What kind of work did you handle?

Yoshiko The theme of the exhibition was the contact point between design and art. Starting with the American artist VASA (whose acrylic works are also in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York), we had many enjoyable exhibitions, such as the teahouse produced by Ikko Tanaka, sculptures by Kan Yasuda, and ceramic art by Fujio Ishimoto of Marimekko, and I learned a lot from them. At first, I helped out about two days a week. I started the gallery as an idea, but I've been running it for 15 years.

― Was he interested in crafts?

Yoshiko That's right. I loved anything that suited my sensibilities, not just crafts, but also architecture and contemporary art.

― From your point of view, what kind of designer was he?

Yoshiko He was always thinking about design. He was very strict when it came to work, but he also loved sports, and he had a good balance between design and fun.

― As the next generation after Yusaku Kamekura and Ikko Tanaka, his generation contributed to the further development of Japanese design.

Yoshiko There were many unique people of his generation, such as Katsumi Asaba, Masuteru Aoba, Takahisa Kamijo, Keisuke Nagatomo, and Makoto Matsunaga, and they all established their own styles. The presence of Mr. Kamekura and Mr. Tanaka was so great that Kojima wondered whether it was okay for him to hold a solo exhibition or compile a collection of his works.

― I met Mr. Kojima at parties and other events, and he was always cheerful and kind, taking care of us. I think that's why he always put his clients first in his work.

Yoshiko That's right. Although he did not always put the client first, he always said that advertising and graphic design should not end up being self-aggrandizing. On the other hand, for volunteer work such as for the Wild Bird Society of Japan, he used designs that reflected his own personality.

― Because of his personality, he must have had many friends.

Yoshiko He did a lot of fun things like soccer, tennis, golf, and traveling, so he had a lot of friends in each of those places. When he was younger, there was a place where designers would gather, and he would go there every day. There, he met people from different industries, interior designers, photographers, sculptors, architects, and he had a great time.

― He was very close to Shiro Kuramata, wasn't he?

Yoshiko They met when they were in our San'ai days, and when they were young, they took a tour of Europe together. When he asked Mr. Kuramata about the interior of our home or the furniture for his office, he readily drew up plans for him. I still use these pieces in our home and office. Kojima has also designed three books of Kuramata's works.

― Thank you very much for your time today. We would like to continue with Ryota.

Interview 2

Interview 02: July 8, 2020 13:30 - 15:00 Location: Kojima Design Office

Interviewee: Ryota Kojima

Interviewers:

Keiko Kubota, Yasuko Seki

Author: Yasuko Seki

Interview: Ryota Kojima

It's hard to leave design archive decisions to the next generation.

Selection based on the "strength" of the design

― The other day, your mother (Yoshiko) told us about Ryohei Kojima's archive, and we would like to hearfrom Ryota. Could you tell us more about it?

Ryota Kojima There were many posters in our collection, and I think there were about 300 in total. I tried to keep at least one of them, and about ten of my best works and those that I felt strongly about. I donated most of them to the CCGA Contemporary Graphic Arts Center of Dai Nippon Printing and to the archive of Musashino Art University. We don't keep a list, but there is a tendency that CCGA has silk works and Musashino Art University has offset works. Silk works tend to be independent works with a social message that were shown at exhibitions, while offset works tend to be commercial works that were commissioned by clients.

― How about something other than a poster?

Ryota Packages and bags are bulky, so we'll use photos instead of the actual products. But I do have a few things related to Uogashi Meicha. As for editorial, I keep the original copies of "High Fashion" and "SPACE MODULATOR", and the rest I keep in scrap form in files. He had a large collection of books, but when we moved I sorted them out according to the criteria of what I wanted to keep, and I keep them in a warehouse and in my office.

― I heard that you shot all his works digitally.

Ryota We asked photographers to shoot not only posters, but also packaging, bags, proofs, prints, sketches, and so on, and over the course of about three months we shot about 4,000 shots in all.

― Do you have a list or data of them?

Ryota Not particularly. I can get an approximation with the office catalogue that my mother gave you.

― Did the staff of the Kojima Design Office make a list of his work and works at that time?

Ryota I remember compiling a list every year for ADC and JAGDA yearbook entries, so if you look for it, you may be able to find some of it. At the Kojima Design Office, we had a "work bag" in which we kept all kinds of sketches and prints. When I was organising them, I picked up the hand-drawn sketches in particular, categorised them as far as I could tell, and left them in clear files.

― From his hand-drawn sketches, we can trace his design process, can't we?

Ryota Sketches remind me of many things. When designing posters, Kojima would sometimes draw freehand bite lines directly on a full-size sheet of Kent paper, and at other times he would use a projector to project a photo or design and adjust the size while copying the outline in pencil onto Kent paper stretched on the wall. Logotypes and logo marks were drawn using a lottery ring and a cloud ruler. I was impressed by his concentration and determination.

― You used to work with him. So you must have a lot of feelings for him, and wasn't it difficult to organise his works?

Ryota That's right. We had tried to preserve as much as possible, but due to storage space constraints, the timing was right, so we narrowed it down to a certain extent.

― After you've gone through all this trouble to organise the works, do you approach museums about donating them?

Ryota We don't make any specific requests. We still receive requests for posters to be displayed in exhibitions, so we keep the major works in storage so that we can respond to those requests. Of course, if someone asks me for help, I would like to donate them all. But even if my generation can keep them, it is difficult to leave the decision to the next generation.

― But I think that Kojima's work is better organised because you are his son and a designer.

Ryota Thank you very much. However, I think that only a limited number of designers, such as Yusaku Kamekura and Ikko Tanaka, will remain as public design archives. As it stands now, it would be difficult for the works of many designers to be preserved as archives.

― I was told that they are currently stored in several locations.

Ryota Posters, part of the collection, sketches, books, photographs, etc. are stored in two locations, while the rest is kept in my office.

― You are storing them in three places. In fact, it is really difficult to preserve the original objects. In the end, the only way is to take digital photographs and preserve them as photographs.

Ryota I think that photographs are simply excellent as records. But the real thing leaves traces of the designer's mind, such as brush pressure and rewriting, so it's fun to be able to imagine all sorts of things from it. Kojima even made his own sketchbooks, so he was very particular about writing down his ideas and notes. The sketchbooks have pieces of tracing paper with ideas in them everywhere, and I'm more inspired by sketches that show the design process rather than the artwork, and I feel it's worth keeping them. It would be nice if there was a place where such things could be collected and stored in one place as an archive.

― When I see the original, I can feel the pressure of Kojima's brushstrokes. And the thumbnail sketches that he drew as memos of his ideas are small, about five centimeters square, aren't they?

Ryota He used to draw sketches with a 2B Uni pencil. He just wrote down sketches as they came to him, or as he came up with them. He drew a lot of designs, went through trial and error, and looked for similar designs.

Original sketchbook cover

What I learned from my father, a designer

― Ryota, you are a graphic designer yourself. What do you think about your father Ryohei Kojima's work?

Ryota Kojima's approach to design was first and foremost to make sure that the people who saw and used the design would feel the "meaning" of it, and then to emphasise the "strength" of the thought that went into the design. I was finally able to ask him about this just before he passed away, and he answered the question, "What do you consider most important when designing? He answered that it was "strength." It is not something superficial and self-centred, but it is the "strength" of the content of the design that is explored through discussion with the partner and formed together through the design process.

― Was that also your criteria for organising?

Ryota In organising the collection, I took a bird's eye view of all of Kojima's work and left the pieces that I felt had the most "strength". I worked with him for about eight years at Kojima Design Office, but we didn't discuss these essential issues until just before he died. He was a member of staff at the office, so I didn't have the chance to ask him.

― What was your father like when you were a child, Ryota?

Ryota After work, my father used to drink until midnight at Barcon in Roppongi, and I have very few memories of playing with him. Even when we did go out together on occasion, he would play soccer or tennis with his friends and I would play by myself. However, I do remember that we enjoyed skiing together.

― Why did you decide to become a designer?

Ryota When I was in elementary school, I would go to the office during summer vacation and draw lines on Kent paper using Rotring. My father would come over and show me the design process, and I found it interesting. I think I was naturally drawn to graphic design work. However, my mother seemed to think that my father was the only designer in the family, and she was against me going into this field.

― Was it difficult for you to work in the same office as your father?

Ryota I never thought that way. We had a clear division of labor. When I started in this business, computers were already mainstream, but Kojima couldn't use one, so he had to work with other staff members to import hand-drawn sketches into the computer and finish them.

― How did Ryota view him as a designer?

Ryota I respected him as a designer. He valued communication with his clients and was always thinking of ways to communicate in a way that was easy for them to understand, and he made every effort to gain knowledge by reading books in a variety of genres. He always tried to do things from the client's point of view, and even if it was just one word, he would stand in the other person's field and replace it with something that the other person could easily understand in his presentation.

― What did you learn from a father like that?

Ryota I think that "designing" is the process of accurately understanding the wishes and desires of the other person, fostering them within yourself, and expressing them in a form.

― What about your design influences?

Ryota I heard that Kojima was fascinated by Bauhaus graduate Herbert Bayer's "World Geographic Atlas" and used it as a model for his design for "Karada no Kagaku (Science of the Body) ", which won a special prize at the Japan Advertising Artists Association (JAFA) in 1965. The subsequent "New Encyclopedia of the Household" was also influenced by Beyer, and when you compare them, you can clearly see that he learned a lot from Beyer's composition and use of colour. Kojima covered and cherished Beyer's book as the starting point of his own design, and it was a great stimulus for me to learn this fact through the organisation work.

― I've been wondering for a while now, what are these sketchbooks?

Ryota Kojima's interests must have been broadened when he was freed from his daily routine, because he always brought a sketchbook with him on his travels and wrote down what he saw and what he liked. Food was the most common subject, but he also wrote down other things he liked, such as Alvar Aalto's architecture. He also made sketches of terrains, museum tickets, shop cards, and pressed flowers. When I look at them, I realise that they are not photographs but sketches, which is very typical of my father, and that he is a man who can move his hands freely. I have about 20 of these travel diaries, and I refer to them when I go abroad.

sketchbook in which he wrote down the things he encountered in various scenes of his journey

― Speaking of Mr. Kojima, his posters for the Wild Bird Society of Japan, which he created as a volunteer, are impressive, but I feel that there are fewer and fewer designers involved in such activities these days.

Ryota I think there are a number of factors behind this, including the aging of the craftspeople involved in printing, the inability to raise production costs, the decline in the number of exhibitions and other venues for presenting works, and the development of inkjet and other digital technologies.

― In the 1970s and 1980s, when they were active, there was still a lot of potential for Japanese design.

Ryota In those days, it was common for them to stay up all night, and they were very busy. Even so, compared to today, I feel that they were able to spend more time on their designs, from idea generation to presentation. Most of the work was done by hand, not digitally, so it must have been hard work, but they had the time and mental space to come up with many ideas and consider them. Nowadays, the time spent on design is reduced because it can be done quickly by computer. We live in a world where we don't think about things very much, and we don't value that time. We need to make more effort to communicate with others.

― Finally, I heard that you are still inheriting Kuramata's furniture.

Ryota It seems that Kojima was a close friend of Mr. Kuramata. I've only met him a few times. Mr. Kuramata designed the furniture in my old house, which I still use to this day. I still use the furniture from Kojima Design Office that Mr. Kuramata designed for him. I will continue to use Kuramata's furniture with great care.

― Thank you very much for your time today. I was able to hear a valuable story about the origins of Kojima Design.